Arts & Culture

Screen Star

Baltimore's most famous screen painter, Johnny Eck, lived an extraordinary life that continues to captivate folklorists, historians, and even hollywood royalty.

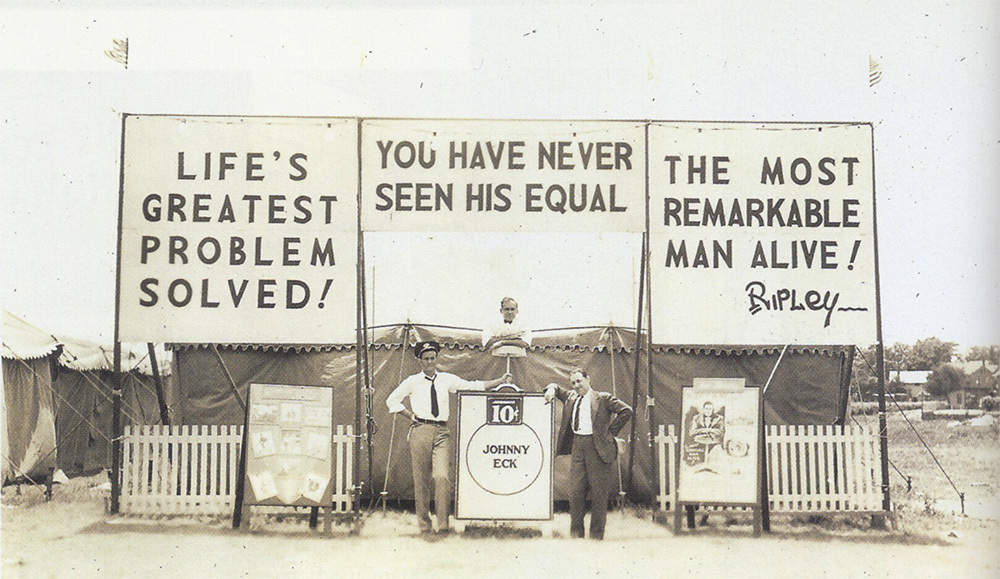

It’s hard to compete for attention with a two-headed calf or a Michael Jackson portrait made from aluminum cans, but Johnny Eck holds his own in such company. On a recent Monday afternoon, visitors circulate through Ripley’s Believe It or Not!’s Inner Harbor location, oohing, aahing, and pointing at the oddities on display. This is no hushed museum crowd, and spontaneous exclamations erupt around the galleries: “Look, this dinosaur is all foil wrappers!” “Hey, that’s the suit worn by the guy who walked over the Grand Canyon!” “It’s John Wilkes Booth’s gun!” The Eck exhibit in Ripley’s “Odditorium” evokes much different reactions.

Eck, a Baltimore native, was born without the lower half of his body and barnstormed across the country as a sideshow act-frequently billed as “the half boy;’ “the world’s greatest living curiosity;’ or, as Robert Ripley dubbed him in the 1930s, “the most remarkable man alive:’ Looped newsreel footage playing on a TV monitor and a dozen or so photos on display show why; in fact, some of the poses are so incongruous they appear to be some sort of optical illusion. One shows Eck perched on the top rung of a ladder, sleeves rolled up, smiling at the camera, and looking casual-but he has no legs, just a torso that appears to have been shorn below the ribcage. In another, he holds himself aloft with his right hand and waves with his left, a pose replicated on a nearby mannequin.

The Eck display stops people in their tracks. A woman holding an infant and talking to a girlfriend spots the photos, does a double take, and falls silent. So does her friend. She squints, furrows her brow, and walks forward, as if pulled by some invisible, magnetic force. She examines each photograph and watches the video loop, twice. When the narrator states that Eck was ”born with a body snapped off at the waist,” she instinctively kisses her child on the forehead.

He was fond of saying he was “the most popular man in East Baltimore,” not the most popular half-man.

Two boys in yarmulkes with Orioles patches sewn onto them stand nearby and are similarly transfixed. “He was born that way,” one says to the other, and they nod in sync.

A few minutes later, another woman slows to a halt. After watching the video, she turns to the mannequin, reaches up, and touches Eck’s raised hand. Then, she moves on to the next gallery.

This sort of thing has been going on for decades, as Eck-who also starred in Freaks, Tod Browning’s classic horror film-has captured the imaginations of folklorists and historians, as well as creative types in search of edgy inspiration. In 2001, Variety reported that Leonardio DiCaprio inked a deal to star in an Eck biopic written by Edward Scissorhands screenwriter Caroline Thompson. A few years later, James Franco was reportedly interested in the role. Legendary cartoonist R. Crumb drew his portrait, and Tom Waits nodded to Eck in a pair of songs, 2002’s “Table Top Joe” and 1993’s “Lucky Day (Overture)” from The Bl,ack Rider operetta. The Rolling Stones included a photo of Eck on the cover of their classic album Exil,e on Main Street.

Such folks tend to focus on the carny years, but Eck also forged a second career as an artist, or, more specifically, a screen painter. The Ripley’s display does include three painted screens on an adjacent wall, but they go largely unnoticed. At one time though, Eck’s painted screens were ubiquitous throughout East Baltimore, where his renown as an artist trumped his sideshow rep.

And as the city marks the 100th anniversary of screen painting, which originated in Eck’s neighborhood, his artistic profile figures to soar. He is the subject of an upcoming exhibition at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), and he’s prominently featured in an authoritative book on the history of painted screens, to be published by the University Press of Mississippi in December. He also appears in the film, The Screen Painters, a 1988 documentary that’s just been re-released on DVD.

Such developments will stoke Eck’s local legend and introduce him to a new generation of fans. Perhaps more importantly, they might also humanize him beyond the “freak” persona.

After all, he was fond of saying he was “the most popular man in East Baltimore;’ not the most popular half-man.

John Eckhardt Jr. and his twin brother, Robert, were born at home, 622 N. Milton Avenue, on August 27, 1911. Through the years, Eck polished the story of his birth, which he fondly shared with interviewers, and it went something like this . . .

During a thunderstorm on a hot summer night, an event occurred in the upstairs bedroom of a red-brick row house that shocked the neighborhood. At 10 o’clock, a baby was born, a normal baby weighing six pounds. The room was dark, lit only by a gas burner and the occasional flash of lightning, so the midwife didn’t see that there was a second child. Twenty minutes later, the midwife exclaimed, “There’s another one!” and that baby emerged. More than half of its body appeared to be missing, and it weighed just two pounds.

Here, the story diverged depending on Eck’s mood and to whom he was speaking.

In one version, he claimed the “monster” baby laid on the bed, ignored by everyone, until an elderly neighbor bent over it and compared it to “a broken doll:’ Then, a nurse picked up the baby and held it up to the light, which caused another neighbor to faint.

In the other version, Johnny told pretty much the same story but ended it with the midwife holding him up and declaring, “This is the most beautiful child I have ever seen.” He then added: “I know I was born into a happy family.”

His father worked as a ship’s carpenter down at the docks and frequented the local saloons. His mother, Emelia, minded the boys and their older sister, Carolyn, and did her best to run the house on meager funds from her husband. She dressed the children in hand-me-downs and customized Johnny’s clothes so they’d fit.

The neighborhood in the 1920s was “like living in the country;’ Eck told folklorist Elaine Eff, who interviewed him extensively in the 1970s and 1980s. “It was peaceful. You could sleep out front in a chair all night in the summer time.”

“He said, ‘I can put that boy on the stage’ and promised my mother the rainbow and the pot of gold.”

Johnny learned to walk on his hands and also got around on a board with wheels attached. He was fond of exploring the lumberyard that occupied most of the block across the street. He played with the workhorses and mules that were kept there and climbed the woodpiles with his brother. “And who was the skyscraper climbing up on the biggest pile?” he asked Eff. “Little John.”

His mother suggested he befriend girls, because she felt boys would be too rough and might damage him. She subscribed to Crippl,ed Chil,d magazine and encouraged Johnny to develop skills. He could read and write at the age of four. He loved drawing and took lessons after school on Wednesdays from shopkeeper William Oktavec, who opened an art store on Monument Street and started something of a local fad by painting on screens. Johnny also learned to type and was soon editing the school paper. His mother hoped he might, one day, be a court stenographer.

But all that changed the day he attended a magic show at a local church auditorium. When the magician, John McAslan, asked for a volunteer from the audience, Johnny answered the call and climbed onstage. His appearance shocked McAslan, who sensed an opportunity and told Emelia her son was a potential goldmine as a performer. “He said, ‘I can put that boy on the stage’ and promised my mother the rainbow and the pot of gold;’ Eck recalled, years later.

His parents signed a contract, and Johnny, with Rob in tow, hit the road. He was 12 years old .

.Johnny eventually hooked up with Sheesley’s Great Shows and learned to swing from a trapeze and walk a tight wire on his hands. He performed magic tricks, juggled, and developed an act with an elephant where he climbed on its head and slid down its trunk. The crowds loved it. He painted his own circus banners, often 20-feet long, using bright and bold colors to attract attention.

Eck saved up enough money to buy his own truck and tent and worked all over the country and into Canada with dozens of other outfits, including Ringling Brothers, Ripley’s, and magician Rajah Raboid. He became friends with legends like Harry Blackstone and found his way to Hollywood, where he starred in Freaks and appeared in Tarzan films with Johnny Weissmuller in the late 1930s.

He especially enjoyed the company of circus people. “[I’d] sit up late and shoot the breeze with some of the most wonderful people in the world;’ Eck once told an interviewer. “I met hundreds of thousands of people, and none finer than the midgets and the Siamese twins and the caterpillar man and the bearded woman and the human seal with the little flippers for hands. I never asked them any embarrassing questions, and they never asked me, and God, it was a great adventure.”

By World War II, it was all over.

When Elaine Eff first went Eck in 1974, he’d been off the road for decades. The grind of travel and being taken advantage of by unscrupulous managers had taken a toll, so Johnny and Rob returned to the house on N. Milton Avenue. They tried their hand at operating a penny arcade and booking a train ride through Rosedale Amusement Company, but both ventures proved unprofitable.

Then, as Rob told Eff, “we got in with [William] Oktavec. He picked us up. If it wasn’t for Oktavec, I’d don’t know where the hell we’d be. We’d be done:’

Oktavec introduced Baltimore to painted screens, an art form that can be traced back to 18th-century London. Oktavec operated a neighborhood grocery at N. Collington and Ashland Avenues, where, in the summer of 1913, he painted pictures of the produce he sold on the shop’s screen door. Soon after, a neighbor, Emma Schott, realized that the painted screen provided privacy from the street, because passersby couldn’t see in, but those inside could see out. Schott tore a page from a calendar of an idyllic scene of a red mill beside a pond and commissioned Oktavec for a screen of her own. It caused quite a stir, and Oktavec painted upwards of 200 similar screens before the summer was done.

Over the next few decades, painted screens spread throughout the city’s east side, with the scene of choice being a bungalow with a red roof and curving path beside a pond with white swans. They became nearly as ubiquitous as marble steps, and it’s estimated that, at the height of their popularity in the 1950s, there were approximately 150,000 screens up around the city.

Eff, who grew up near Mt. Washington, happened upon painted screens while studying folk art at State University of New York at Oneonta’s Cooperstown Graduate Program. Working as a curatorial assistant with the New York State Historical Association, she was removing frames from a stack of paintings and noticed that two of the pieces, dating back to the 1890s, were done on screens. They reminded her of the painted screens in her hometown, something clicked, and she returned to Baltimore and began documenting the work of Oktavec, Eck, and many others.

Since then, she’s produced two definitive works on the subject: the 1988 Screen Painters documentary and a thoroughly researched, gorgeous coffee-table book, The Painted Screens of Baltimore, which comes out in December. She is curating the upcoming MICA exhibition, The Painted Screens of Baltimore and Beyond. “Three hundred years ago in England, they were used primarily in commercial settings and among the wealthy,” says Eff. “You wouldn’t find a street full of them like in Baltimore. Baltimore completely embraced them and made them their own:’

And Eff embraced Eck during his years as a screen painter, spending many hours at his house, which, she recalls, appeared to be occupied by a pack rat who happened to be a foot-and-a-half tall. Everything, including piles of National Geographic magazines and cans of Wiedemann’s beer, had to be on the floor within Johnny’s reach. He kept his paints, screens, and some canvases near the stairs in the front room, which he used as a painting studio. (He tested paints in the backyard, and if you walk down the alley today, you’ll notice bricks painted red, green, blue, and yellow-none higher than three feet off of the ground.)

Eck held court on his front stoop, often flanked by a beloved dog, Reds or Major, both Chihuahuas that were smaller than him. “I saw him just about every day when I was a kid;’ says Michele Perrera, who grew up nearby on S. Montford Avenue. “He was a character, and people looked out for him:’

‘We knew him as a neighbor, but also as an artist;’ says her mother, Marge Shaw. “He would make cards for us, write calligraphy, and, of course, he did the screens.”

Eck was known for bold colors—the same colors he used on the circus banners he painted.

Eck had a unique style. Like a lot of screen painters, he got his ideas from greeting cards or calendars, but Eck was known for bold colors—the same colors he used on the circus banners he painted—and variations on the usual imagery. Instead of painting the standard bungalow with a red roof, he’d paint a bright blue roof. He painted tugboats in Fells Point, the pagoda in Patterson Park, and Arabbers hawking their produce. He once painted Jesus standing on the shore looking out toward fishermen casting a net into the sea. At first glance, Jesus appears to be waving to them, but, on closer examination, he’s giving them the finger.

Eff has assembled a representative crosssection of Eck screens for the MI CA show, which will run concurrently with The Amazing Johnny Eck, an exhibition of memorabilia collected by Eck archivist/historian Jeffrey Pratt Gordon.

Gordon became obsessed with Eck while working as assistant prop master on Homicide: Life on the Street and The Wire. He came across many of Eck’s belongings in a Fells Point antique shop and bought the entire lot. The haul-which is being digitally archived at Gordon’s johnnyeckmuseum.com website—included letters, drawings, photographs, publicity material, props from his tent shows, trunks of clothing, a scrapbook from Freaks, diaries, handmade puppets, a miniature circus made by Eck, audio cassettes, and, of course, painted screens. Gordon, who continues searching for Eck-related items, owns the last screen he ever painted: a leprechaun standing beside a pot of gold.

A carefully curated selection of pieces will be on view at MICA, including previously unseen items such as a cache of erotic drawings that Eck made and hid in the basement, along with his collection of Tijuana bibles and naughty magazines. “He was known as this happy-go-lucky guy, but he was also working out issues related to sex and to death;’ says Gordon, who notes that the racy material will be off-limits to children at the exhibition. “People tend to forget that he had a full range of feelings and emotions just like the rest of us, and I want the exhibition to paint a full picture of who he was:’

Gerald Ross, MICA’s director of exhibitions, echoes and amplifies that point. “I think it is absolutely essential for artists, both young and old, to seek an understanding of the human condition;’ he says. “This exhibition shows the mind of a man whose life could have gone in a very different direction, grappling with being forever on the ‘outside: Instead, he embraced life and filled it with artistic passion and love for humanity:’

Gordon keenly understands the power of that message as it relates to Eck’s life. Through the website, he hears from people with disabilities, amputees, and combat veterans who’ve lost limbs-all saying they were inspired by Eck and the life he led. “Despite everything, Johnny was a whole man and lived a full life;’ says Gordon. ”When you see someone like him making the best of it, it’s inspiring. You start to believe you can do anything you set your mind to:’

On a recent afternoon, Ron Spence sits in a folding chair outside his house on N. Milton Avenue. He’s never heard of Eck, who died in his sleep-in the house where he was born, a few doors away from Spence’s-on January 5, 1991. By that time, Eck no longer held court on the front steps, and he and Rob (who passed away four years later) had become reclusive. In 1988, someone broke into their house and pistol-whipped Johnny, who couldn’t defend himself. The incident broke his spirit and drove him inside.

Standing nearby, Spence’s wife, Melissa, perks up after hearing Eck’s name. She says his house has been vacant for a long time and recalls the day workers with cranes installed 800-pound metal doors on it, front and back. Melissa assumed she met Eck’s son that day, but it was Gordon, who’d purchased the house with hopes of turning it into a museum, hence the fortified doors and windows.

A neighbor by the name of Ms. Cleo, now deceased, told her about its former occupant. “She told me about his condition and said he had all the neighborhood kids around him;’ says Melissa. “He painted, and he was a good artist, too. In fact, he painted a bunch of screens in this neighborhood:’

She points to her neighbor’s basement window: “He did that screen right there:’

Nearly frayed out of its frame, the screen is washed out and faded. No signature is visible. But look closely and you can see, though it’s awfully faint, a pond and two swans with stands of trees on either side of a bungalow. Its roof is painted blue.