Travel & Outdoors

Mountain High

Get away from it all in a town bursting with a vibrant music scene and plenty of local color.

It’s 7 p.m. and what sounds like a stampede has overtaken this country store. Inside, merchandise is pushed up against the walls, and the store is transformed into an old-fashioned music hall. Dancers are the source of all the racket—old-timers sporting overalls, middle-aged couples dressed for a square dance, and twentysomethings in jeans. Many wear taps under the heels and toes of their cowboy boots and shoes, as they shuffle up a storm Appalachian-style, keeping time with the banjo and fiddlers on the bandstand. Throughout the night, new bands take the stage, the tunes always tied to genres of traditional American music—mountain, bluegrass, classic country. And the dancing never stops.

Welcome to the Friday Night Jamboree at The Floyd Country Store (206 S. Locust St., 540-745-4563) in Floyd, VA, a mountain town of about 430 full-time residents. What’s so surprising about this tiny spot on the Blue Ridge Plateau is how much is happening here. Take this night, for example. Along with the jamboree, musicians stage open jam sessions on the street—there’s even one inside a barber shop with fiddlers ranging from wizened old men to a boy in his teens. Restaurants teem with diners, and, since it’s Friday, people pass by with wares from the nearby artisan mart.

So why haven’t you heard of Floyd? Well, finding it isn’t easy. From I-81, about 30 minutes south of Blacksburg, the twisty, 20-mile journey down tiny Route 8 is arduous enough to deter a casual traveler. Others skirt it while driving the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway. But Baltimoreans seeking a unique and unexpectedly affordable getaway will delight in the five-hour trek.

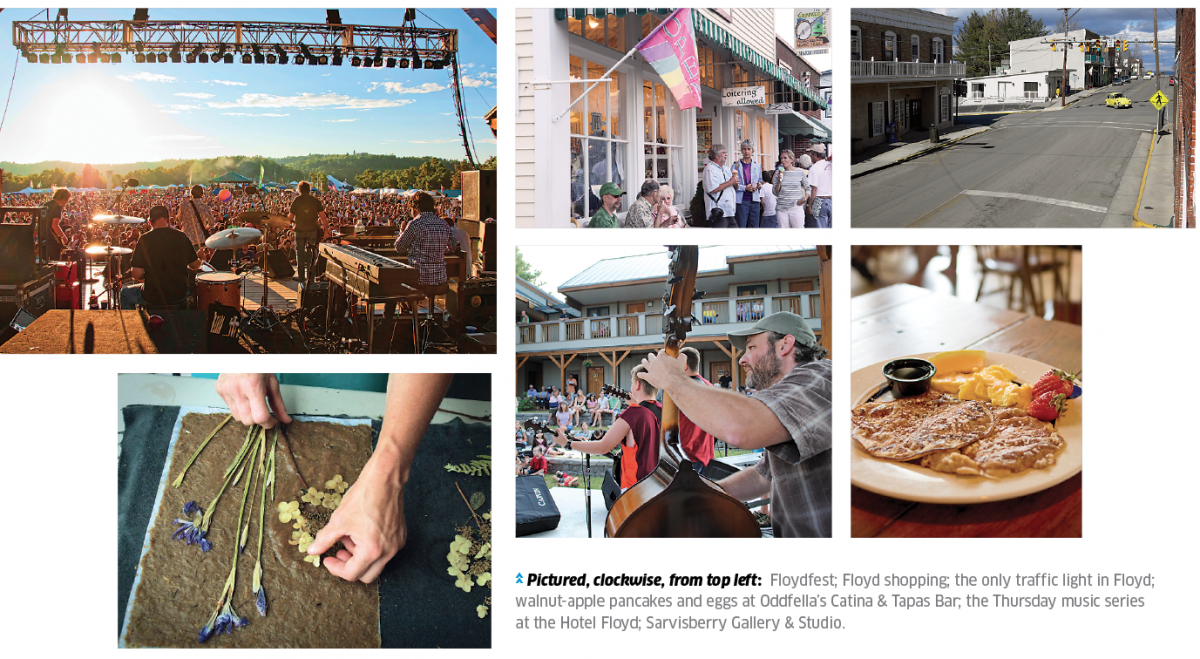

In 2003, Floyd emerged from a mere dot on the map in southwest Virginia’s Bible Belt to become a major destination on The Crooked Road, a trail of traditional American music venues featuring bluegrass, country string bands, blues, and gospel. Every year in July, American heritage music enthusiasts flock here for FloydFest, held in Rocky Knob (894 Rock Castle Gorge, 888-823-3787), a scenic recreation area on The Blue Ridge Parkway, about 10 miles out of town. This once-grassroots Appalachian Lollapalooza has morphed into a five-day, multi-generational Americana music marathon. This year’s lineup includes Emmylou Harris and Grace Potter. Plus, there are more than 70 artisans, homegrown food, a healing-arts village, and outdoor activities.

What’s unique about Floyd is its residents. Locals describe the population as a fusion of tie-dye and overalls. Originally a farming community, the town experienced a rebirth in the 1970s, when a group of counterculturists moved in. Drawn to the town’s organic roots, natural beauty, and lack of land restrictions, the “hippies” established a community dedicated to living close to the land. The contrast between a conservative farming community and entrepreneurial artisans, musicians, and New Agers might be contentious in most places, but that union defines the vibe here.

Eat Local

Organic food isn’t a new trend in Floyd, it’s just how it’s always been—whole food, locally grown, seasonally consumed. Members of the town’s progressive movement have founded SustainFloyd (203 S. Locust St., Suite H, 540-745-7333), which helps longtime farmers manage their land. Most people in Floyd have gardens and get their eggs from neighbors. And, they’ve started organic farms of their own. It’s by necessity—the closest mall is 45 minutes away, and the nearest airport is close to an hour.

Floyd’s produce, dairy, and meat farms sell on-site and at the Saturday farmers’ market (205 S. Locust St., 540-745-7333). The town also has a number of fresh-food purveyors, including Grateful Bread (109 Old Hensley Rd., 540-558-9395), known around town for everything from foccacia to cinnamon rolls. Red Rooster (117 S. Locust St., 540-745-7337), an organic coffee roaster, also runs the cafe Black Water Loft (117 S. Locust St., 540-745-5638), a lively spot where locals like to catch up over an oatmeal cream pie and a latte.

For a small town, Floyd offers an impressive array of dining choices that base their menus around seasonal, local ingredients. Pine Tavern (611 Floyd Hwy. N., 540-745-4482) serves family-style Southern comfort food such as fried chicken and mashed potatoes, while Dogtown Roadhouse (302 S. Locust St., 540-745-6836) makes wood-fired pizzas with gooey mozzarella, local sausage, and caramalized onions. Fat Spoon Café (274 Floyd Hwy. S., 540-745-4446), owned by Rich Perry, who has cooked for the Bush family, features home fare at prices not seen for years in D.C.—the vegetarian buffet is $8; the one that includes meat is $10. The menu at Oddfella’s Cantina & Tapas Bar (110 N. Locust St., 540-745-3463), housed in a circa-1910 meeting hall, is described as “conscious comfort food with an Appalachian-Latino twist.” The offerings, such as barbecued tempeh and grass-fed beef chimichangas, don’t disappoint.

Shopping on “Floyd Time”

When it comes to shopping in Floyd, be warned that it is anything but a one-and-done experience. Shopkeepers will greet you with, “Well, come on in!” like you are visiting their homes, and often will serve tea, fully expecting you to stay and chat. In fact, locals call it “running on Floyd time.”

The town is chock-full of craft shops and galleries, like New Mountain Mercantile (114 S. Locust St. #A, 540-745-4278) and Troika Contemporary Crafts Gallery (203 S. Locust St. #K, 540-745-8764), that display regional artists’ handicrafts—handmade flutes and chimes, pottery, and eco-chic clothing. Quilts are treasured in these parts, so if you find one you like for sale, buy it—many fabricators keep them as heirlooms. If you are so inspired, you can learn to make your own, and Schoolhouse Fabrics (220 N. Locust St., 540-745-4561) provides materials. Its sign reads, “Come in and spend the day”—and you just might. It’s a three-floor menagerie of breathtaking fabrics, trims, and threads.

Farmers Supply (101 E. Main St., 540-745-4455), Floyd’s hardware store, is worth a visit. A throwback to the old days, it sells feed, seed, and maintenance supplies, but also a hodgepodge of unlikely items, like manually operated kitchen gadgets (e.g. a hand-press juicer and serrated grapefruit spoons for digging out the fruit).

You’ve Gotta Have Art

A number of artists have studios in the countryside, mapped out on the Floyd Artisan Trail (540-745-7333 or 540-230-7955). In her Sarvisberry Gallery & Studio (174 Sarvisberry Ln., 540-745-6330), Gibby Waitzkin creates paper by harvesting fiber from her own plants and devising organic dyes from her flowers. She incorporates the paper into multimedia photography. Bill and Corinne Graefe of Phoenix Hardwoods (2540 Floyd Hwy. N., 540-745-7475) create furniture from hardwoods they mill.

Throughout the year, art collectors flock to Floyd for a variety of open studio events, including the twice yearly 16 Hands Tour of the area’s pottery studios. Town leaders helped turn an old dairy barn into the Jacksonville Center for the Arts (220 Parkway Ln. S., 540-745-2784), which houses artist spaces, galleries, classes, and one of only three elevators in the county. You can take a jewelry-making class, or stop by to see a local work. Even the only hotel within walking distance of Main Street has an artistic bent. Each guest room at The Hotel Floyd (300 Rick Lewis Way, 540-745-6080), which was constructed with sustainable materials, is decorated by a different business or cultural organization. You can sleep under concert memorabilia in the Floydfest room or admire pottery in the one named for the 16 Hands Tour. If you miss the Friday Night Jamboree, The Floyd Country Store gets rocking again on Saturday and Sunday afternoons. The Music In The Mountains series runs Thursday nights from May through October on the town’s bandstand.

Floyd didn’t have its own tourism board until September 2014 when the town created a website and a new visitor center, filled with information about the area’s music and arts venues and scenic drives, plus a friendly local staff. But it keeps a low profile, and speaks to the town’s laid-back sensibility.

On a Saturday morning, for example, you’ll likely see a sleepy-eyed musician sipping his morning joe beside an elderly farmer in town to pick up seed. They’ll chat with a mom and her son about a recent little league game.

Oddfella’s restaurant owner Kerry Underwood appreciates that locals value individuality. He created a distillery, slated to open this summer, in the town’s renovated water-treatment plant, where he’ll make his own moonshine and brandies from family recipes. Underwood defines the town with a longstanding phrase used so often the tourism council adopted it: “Floyd, it’s a state of mind.”

Going to the Dogs

Winery offers day trip for guests, human and canine.

If you and your pooch want to take in the Blue Ridge mountain air, just roll off the exit between mile markers 171 and 172 and stop at the Chateau Morrisette winery (Milepost 171.5 Blue Ridge Pkwy., 540-593-2865). You’ll pull up to two fancy French chateau-style buildings overlooking a sweeping, verdant valley, and the spectacular Buffalo Mountain.

When the Morrisette family planted the first grapes in 1978, Chateau Morrisette was Virginia’s only production winery. Now, it’s one of the largest. Chateau Morrisette produces more than 60,000 cases of traditional French and hybrid varieties each year. The exquisite tasting room, housed in one of the largest salvaged-timber-framed buildings in the United States, offers 10 tasting wines, which rotate weekly. The second building contains Chateau Morrisette’s acclaimed restaurant, serving seasonally inspired Southern fare prepared with ingredients from the organic garden. Added bonus: The winery is pet-friendly. Visitors can dine with their dogs on the deck, taking in 180-degree panoramic views of the mountains, and people and pets attend the winery’s popular music festivals throughout the year.

The story behind this pet-friendliness goes like this: In the 1990s, David Morrisette, then chief winemaker and son of the founders, decided to rename some of the wines after his dog Hans—who was renowned for licking up spilled red wine. Morrisette slapped a rendering of the dog on the labels, and immediately, sales rose 200 percent. Intrigued by the spike in sales, he branded more of his red wine varietals with canine names and plastered them with Hans’ likeness. Sales leapt exponentially. Since then, practically every Chateau Morrisette bottle bears an image of a black lab and a handful have canine-inspired names.