Arts & Culture

Tupac Was Here

The legendary rapper spent his formative years in Baltimore.

In the public imagination, Tupac Shakur will always be a West Coast figure. California is, after all, where he gained fame as the embodiment of the platinum-tongued hip-hop star—the feuding, gun-toting, authority snubbing anti-hero. It’s where he radiated Hollywood-sanctioned sex appeal, stoking tabloid tales that made him a mainstream celebrity.

The fact is Shakur lived most of his life on the East Coast—including four extraordinary years in Baltimore. But that time doesn’t get much play. The 2003 Oscar-nominated documentary Tupac: Resurrection, for instance, ran nearly two hours but devoted less than two minutes to Shakur’s life here. That’s a shame, because it’s key to understanding a man who’s become a cultural icon.

Shakur was shot and killed in Las Vegas 24 years ago. The media frenzy that ensued focused mainly on violent song lyrics, previous shooting incidents, and a simmering East Coast versus West Coast rap feud. The emerging narrative dovetailed conveniently with the “thug life” that Shakur embraced while living in Oakland and Los Angeles and became legend over the next two decades.

These days, Shakur gets compared to the likes of John Lennon and Bob Marley, and regularly turns up on lists of all-time greatest artists and rappers. Shakur has also been the subject of theater productions, museum exhibits, and college courses. The Library of Congress added his song, “Dear Mama,” to the National Recording Registry in 2010. A New York Times Magazine piece on Kenya noted that vehicles in Nairobi are often adorned with images of Jesus Christ and Tupac Shakur.

“He’s more relevant than ever, not just here in America, but all over the globe,” activist and writer Kevin Powell told ABC News on the anniversary of Shakur’s 40th birthday in 2011. “He really is the most significant icon that hip-hop has ever produced.”

And Baltimore played a major role in Shakur’s development, not as a rough-riding hip-hop superhero, but as an artist.

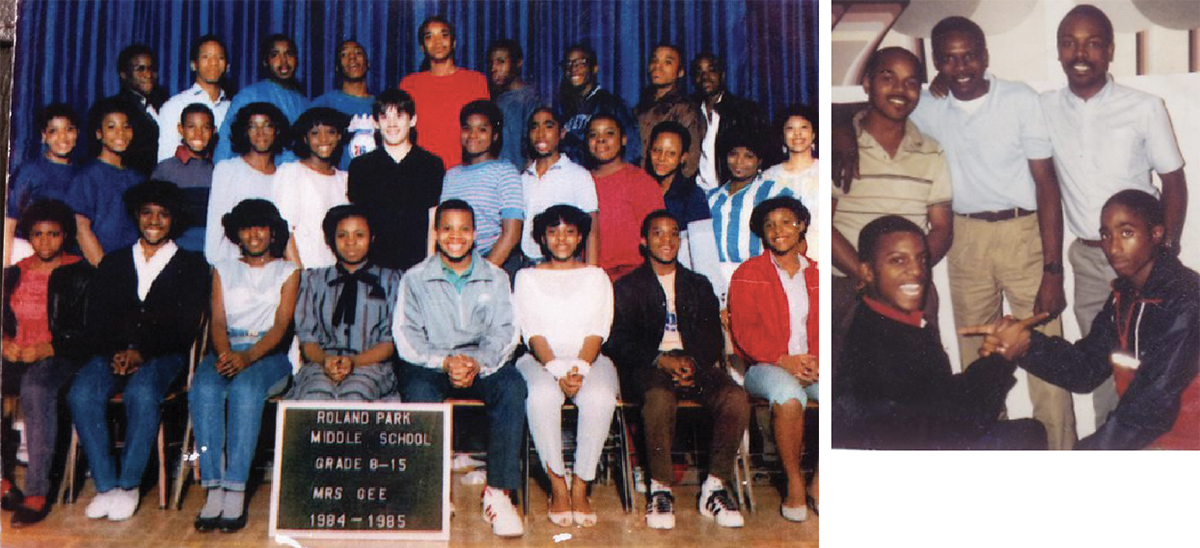

At age 13, Shakur moved to Baltimore from New York City in 1984 with his mother, Afeni, and younger sister, Sekyiwa. The family lived in the first-floor apartment of a brick row house at 3955 Greenmount Avenue in the small, North Baltimore neighborhood of Pen Lucy. Tupac went to Roland Park Middle School for the eighth grade.

That year’s photo for Mrs. Gee’s class shows him in the second row, near the center. With close-cropped hair and dressed in a light-colored, short-sleeve shirt, he looks lanky, even scrawny, among his classmates. Still, it’s easy to spot him thanks to his thick black eyebrows and dark eyes. And then there’s the mouth. While the other kids sport tight-lipped smiles or teeth-baring “say cheese” grins, Shakur strikes an altogether different pose. Actually, he doesn’t appear posed at all. His mouth is open wide, and he seems engaged, not docile or mindlessly compliant. It looks like he might be talking to the photographer.

Dana Smith sits in the front row, to Shakur’s left. Smith, nicknamed “Mouse Man,” forged a musical bond with Shakur and remembers the first time he spoke to him on the bus home from school. That day, in September 1984, the No. 8 bus was nearly full and Shakur took the only open seat, the seat beside Smith, who was itching to get home and listen to WEBB’s Rap Attack show at four o’clock.

“He kicked a rhyme to me, and I was like, ‘Whoa, this is crazy.’”

Smith, a talented beatboxer, asked the newcomer if he was into hip-hop and knew how to rap. “He kicked a rhyme to me, and I was like, ‘Whoa, this is crazy. It was really good.” He later learned the rhyme wasn’t original—it was actually lifted from a Kurtis Blow song Shakur knew from New York, which hadn’t made it to Baltimore yet.

Their friendship blossomed, rooted in a shared love of hip-hop acts like Eric B & Rakim and Run DMC and an appreciation of different types of music. As Smith recounts the story, he walks around The Sound Garden, the now venerable Fells Point record store, and points out some of the nonrap music Shakur enjoyed. Kate Bush? “Yes, indeed,” says Smith. “‘Wuthering Heights’ was the song.”

Sting? Yup. Steve Winwood? Yup. “Hey, we were also listening to Brian & O’Brien on B104, playing the hits all day long,” he says, referring to the then-popular top 40 radio program.

Smith picks up a CD copy of Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms. It, too, was a favorite, but not for hits like “Money for Nothing.” Smith starts singing lyrics from the title track that resonated: “Through these fields of destruction/Baptisms of fire.” The tune, sung by Brit Mark Knopfler, traces a protagonist who faces death and treasures his comrades’ loyalty—ground Shakur covered in songs he later wrote.

When asked about this type of music’s appeal back in the day, Smith claims much of it was practical, a lesson in song craft: “For us, it was all about identifying transitions in songs and how smooth they were.”

They would meet up every afternoon to write rhymes, after Smith finished his homework. Sometimes, they’d hang out at a rec center on Old York Road, but Shakur wasn’t into playing basketball or pingpong, because “he sucked at sports, all sports,” says Smith. Most often, the two of them simply composed raps, either sitting inside a plastic bubble on the playground behind Shakur’s house—“the acoustics were so good in there,” recalls Smith—or hunkered down in Smith’s basement on nearby 41st Street.

Smith’s house was lively, populated by an array of family members including grandparents, his mother, an aunt, and two uncles. Music was always playing. Smith was the youngest of his group of friends, a self-professed “good kid, the freshest kid on the block” who had all the latest fashionable clothes and sneakers, thanks to his uncles, who dealt drugs in the neighborhood.

Shakur, on the other hand, came from poverty. His father wasn’t around; his mother had been arrested and charged with conspiracy to bomb New York City landmarks while a member of the Black Panther Party in 1969. A month after being acquitted of the charges, she gave birth to Shakur, on June 16, 1971. Afeni, who passed away in May and was the inspiration behind the song “Dear Mama,” struggled with substance abuse issues (“And even as a crack fiend, mama/You always was a black queen, mama”) and with supporting the family (“You just working with the scraps you was given/And mama made miracles every Thanksgiving”).

Shakur wore hand-me-downs, including pants that were so big they had to be stapled. He slept in a small bedroom, while his mother and little sister slept in the dining room Afeni had converted into a bedroom. Smith says the Shakur house was “always dark, dim. They had lights and it was clean, but it was dark with not a lot of stuff in there.”

Smith’s family and friends razzed him for befriending the raggedy newcomer. “This guy is cornball—everything about him is corny,” he recalls them saying. “Why are you hanging out with him?”

The answer, says Smith, was simple: “We loved to rap.”

In the mid-1980s, rap wasn’t yet the commercial juggernaut it has become—it was gaining popularity, but hadn’t arrived in the mainstream. The Enoch Pratt Free Library, ahead of the curve, sponsored a youth rap contest in November 1985. Shakur spotted a flier with “Calling All Rappers!” across the top, urging anyone under the age of 18 to “write the best rap about the Pratt Library and be eligible for a cash prize.” All entrants had to submit a written copy in advance (“No Profanity Allowed”), and the finalists performed at the library at Pennsylvania and North avenues.

Shakur and Smith created “Library Rap,” which Shakur wrote out in longhand, in black pen, on a piece of lined notebook paper, and he and Smith’s group The East-Side Crew entered the contest. Deborah Taylor, then the Pratt’s young adult services coordinator, organized the contest and remembers Shakur and Smith as “very polite boys. They were nice kids.” She drove them to the contest because they didn’t have transportation.

Shakur and Smith’s winning performance opened with Shakur declaring, “Yo’ Enoch Pratt, bust this!” and urging Baltimoreans to get library cards. They told kids to stay in school, learn to read, and “get all the credits that you need.” (Shakur’s handwritten verses now reside in the Pratt’s Special Collections archive, alongside works by H.L. Mencken and Edgar Allan Poe.)

Taylor, who still works at the Pratt, recalls all the judges commenting on the same thing: The scrawny kid lit up the room with his rapping. “When Tupac performed,” she says, “you could not take your eyes off him.”

Shakur and Smith performed whenever and wherever they could: for the drug dealers working on Old York Road, opening for rap group Mantronix at the Cherry Hill rec center, and even at neighborhood funerals. They also wrote rhymes with titles like “Babies Havin’ Babies” and “Genocide Rap” that reflected the political and social awareness Shakur inherited from his mother.

“Tupac was always conscious of that shit,” says Smith. “He schooled us on those sort of social justice issues, and hip-hop was the perfect outlet. It allowed us to say what was on our mind, and people listened.”

After his freshman year at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, Shakur, wanting to hone his performance skills, auditioned for the Baltimore School for the Arts (BSA) as a theater major. Smith helped Shakur, who’d appeared in a community production of A Raisin in the Sun while in New York, run lines from a scene for his audition piece. “We worked on it for weeks,” says Smith. “You could tell he was destined.”

Donald Hicken saw something similar. Hicken, who recently retired as the head of BSA’s theater department, remembers Shakur auditioning. “It was so good,” he says, “and the first thing I noticed was that he was extremely charismatic. From the very beginning, we all sensed he was the real deal.”

For an assignment, Hicken asked students to create a movement piece based on “a song that speaks to you in a very personal way.” Shakur chose Don McLean’s “Vincent (Starry, Starry Night),” a song about Vincent van Gogh by the songwriter best known for “American Pie.” It included lines like “you suffered for your sanity” and connected that suffering to being misjudged: “They would not listen, they did not know how/Perhaps they’ll listen now.”

“Tupac said the song was about a misunderstood artist,” says Hicken, “about someone who was an artist but couldn’t be taken seriously because of the world he was in. That’s how the song spoke to him.”

Shakur embraced being a theater artist during his two years at BSA, studying the likes of Henrik Ibsen, Sam Shepard, and Shakespeare. “He was incredibly bright and had a lot of intellectual curiosity, though he wasn’t an especially good student academically,” Hicken says. Shakur often spent his lunch break reading in the school library.

He forged tight friendships with fellow theater student Jada Pinkett and visual artist John Cole. “Pac was always intense, extremely passionate,” Pinkett says in the book Tupac Remembered. “He loved Shakespeare. . . . Acting was a part of his spirit. He really loved it.”

Shakur stayed at Cole’s Reservoir Hill apartment for a while, and bussed tables at the Fish Market near the Inner Harbor with Smith and BSA friend Darrin Keith Bastfield. “[Tupac] was always on stage,” says Cole in the tribute book. “He was always entertaining, always hammin’ it up.”

Bastfield recalls hanging with Shakur at a friend’s apartment and asking what type of actor he wanted to be. “A Shakespearean actor,” Shakur replied, “because you have to be the very best in order to do Shakespeare.”

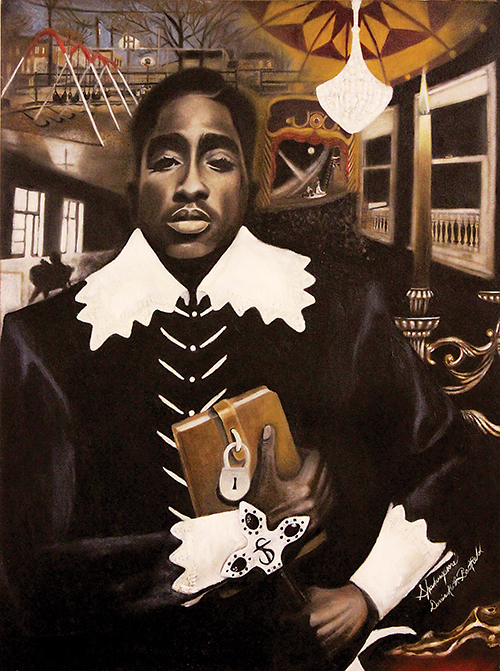

Bastfield joked that he could picture him decked out in a ruffled collar and tights. Shakur then struck a Shakespearean pose, and Bastfield, an aspiring visual artist and rapper himself, grabbed a pen and paper and started sketching a portrait. “Someday, this will be a painting called Shakurspeare,” Bastfield quipped. They both laughed.

“Our songs spoke about loyalty and friendship.”

Despite his gifts as an actor—which eventually led to roles in films like Poetic Justice and Juice—Shakur never wavered from his fierce commitment to hip-hop. During the walk home from their restaurant job, Shakur and his friends would sometimes mount Hopkins Plaza’s outdoor stage and rehearse a late-night set of rap tunes.

Shakur and Smith teamed with Bastfield and Gerard Young to form a new group, Born Busy. They made tapes that are considered Shakur’s first recordings—eight songs that remain unreleased. “We rapped, wrote our stuff, and worked every day,” says Bastfield, whose book about Shakur, Back in the Day: My Life and Times With Tupac Shakur, was published in 2003. “Our songs spoke about loyalty and friendship. We were big on that.”

Just prior to his senior year, Shakur, with tears in his eyes, told Hicken he’d be moving with his family to Marin City, Calif., where his mother hoped to get a fresh start. Hicken offered to find him a host family so he could graduate from BSA, but Shakur said he couldn’t abandon his family. The Shakurs left Baltimore in the summer of 1988.

As he shot to stardom, the subsequent years were a whirlwind of recording sessions and concert tours punctuated by late-night partying, violent brawls, multiple shootings, and a stint in prison for sexually abusing a fan. (Shakur maintained that he “committed no crime.”) Such behavior bewildered his Baltimore friends. Though they’d kept in touch (Smith even went to the West Coast to help Shakur write records), they barely recognized the figure on the national stage. They recognized the immense talent and dazzling magnetism, but little else.

On Sept. 7, 1996, Shakur was attacked by a drive-by shooter on the Las Vegas Strip, and he passed away Sept. 13. During the six days he was on life support, he reportedly stirred and regained consciousness just once—when a girlfriend brought a CD player to the hospital and played him Don McLean’s “Vincent (Starry, Starry Night).”

The house at 3955 Greenmount Avenue has no historic marker or plaque indicating its connection to an American cultural icon. On a hot summer day, the shades are drawn, and the place looks as if it’s unoccupied. Next door, a couple sitting on the front porch say they know of the house’s significance—pretty much everyone in the neighborhood does.

As they talk, a lean, solidly built man emerges from 3955 and closes the door. He wears an Orioles tank top and cargo shorts with a bucket hat pulled over his eyes. He also knows about Shakur and, when asked if he’d like to say anything about the house’s history, says, “No, no, no,” and walks off.

Just then, a woman joins the couple. She introduces herself as Diamond and says she’s 20 years old. “When I first moved here, I wondered, ‘Why are people taking pictures of our house?’” she says. “Then, I realized they were tourists, taking pictures of Tupac’s house next door.” She spots them six or seven times a month, even when it snows.

When asked if she listens to Shakur’s music, she says, “Of course I do.” And the surprised look on her face suggests a question of her own: “Doesn’t everyone?”

Diamond claims “Dear Mama” as a favorite song, and hums a line—“Everything will be alright if ya hold on”—but goes no further.

She smiles, and says, “Yeah, Tupac was here.”