News & Community

Smoke Screen

The 1967 riot may have obscured the work of civil rights hero Gloria Richardson, but her legacy shines on in Cambridge.

and-lettered posters started appearing on telephone poles around Cambridge a few days before the civil rights rally scheduled for July 24. Hung throughout the predominantly black Second Ward, the posters touted H. Rap Brown, head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), as guest speaker. Brown was a polarizing national figure known for his “violence is as American as cherry pie” militancy, and Cambridge was on edge.

and-lettered posters started appearing on telephone poles around Cambridge a few days before the civil rights rally scheduled for July 24. Hung throughout the predominantly black Second Ward, the posters touted H. Rap Brown, head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), as guest speaker. Brown was a polarizing national figure known for his “violence is as American as cherry pie” militancy, and Cambridge was on edge.

By that summer of 1967, the small Eastern Shore town—population roughly 12,000, same as today—had experienced a few years of relative calm, after long-simmering racial tensions sparked headline-making unrest in the early 1960s. Cambridge had become a vital center of civil rights activism from 1962 to 1964, thanks, in large part, to Gloria Richardson, a 45-year-old, Howard University-educated mother of two, who steered the local movement and had the ear of leaders like Robert Kennedy and Malcolm X. But Richardson had relocated to New York City two years before the 1967 rally and, without her at the helm, the situation was particularly tenuous.

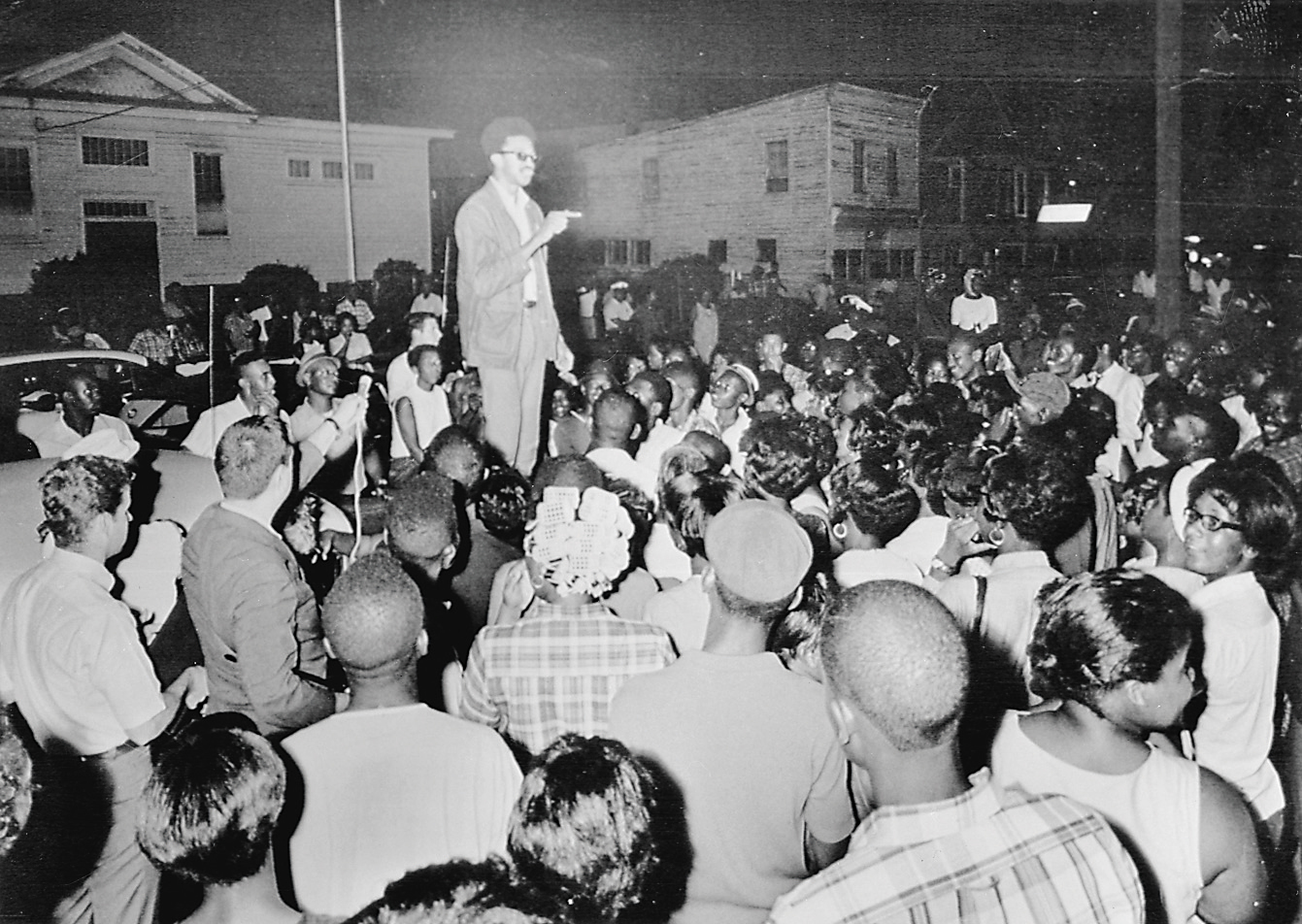

For nearly an hour, Brown railed against government hypocrisy, institutionalized racism, and the philosophy of non-violence.

H. RaP Brown in cambridge on July 24, 1967, standing atop a car to urge action by the african-american community.

—Getty Images

On the night of the rally, a crowd of 400 gathered across the street from the vacant, historically black Pine Street Elementary School, which had recently been torched by an arsonist, and awaited Brown, who was running more than an hour late. When he finally arrived, Brown, wearing his trademark dark glasses and a long denim jacket, jumped atop a parked car and launched into a speech about black power, which he defined as being able to “control our community.”

For nearly an hour, Brown railed against government hypocrisy, institutionalized racism—at one point noting that Cambridge had never had a black mayor—and the philosophy of nonviolence, ending with a plea for blacks to “fight the man” by hitting him where it hurts: his pockets, because money was the only thing the white man respected.

But he also cautioned his listeners: “When you move to get him, don’t tear up your stuff,” Brown implored, “don’t tear up your brother’s stuff, hear?” In fact, those were his parting words.

The national guard on pine street the day after the 1967 riot. —D.C. Public Library

After the speech, Brown (currently serving a life sentence for the 2000 shooting of two Georgia sheriff deputies) and others were escorting a woman home when shots were fired, and he was struck in the head by buckshot. Brown suffered minor injuries, was treated at the hospital, and secreted out of town. Later that night, a car carrying white teenagers sped down Pine Street and reportedly drew gunfire; in a separate incident, a Cambridge policeman was shot in the Second Ward; and, at one o’clock in the morning, the Pine Street school was, once again, set ablaze.

Fearing violence, local firefighters refused to enter the Second Ward and, instead, parked their trucks along the perimeter of the white business district. Meanwhile, burning cinders breezed from the school to buildings in the black business district, setting them ablaze. A bucket brigade of residents battled the fire and pleaded with firefighters to help, to no avail.

Finally, Maryland Attorney General Francis Burch, who had been called to the scene, grabbed a hard hat and fireman’s coat and jumped in a hook and ladder truck. But the blaze was already out of control and would claim two blocks in the Second Ward, 20 buildings in all, by daybreak.

Coming on the heels of unrest in Cincinnati, Newark, and Detroit, the incident made headlines across the country, the National Guard was brought in, and a warrant, for inciting a riot, was issued for Brown. Gov. Spiro Agnew vowed to bring Brown and other militants to justice, a hard-line stance that helped catapult the former Baltimore County executive to national prominence and, eventually, the White House, as vice president in the Nixon administration.

Over the next few years, Brown would remain in the news thanks to numerous court appearances and legal wrangling, virtually assuring Cambridge’s notoriety as the site of the “Rap Brown riot.”

“The press likes to say ‘the Rap Brown riot’ and conveniently ignore everything that came before it,” says Richardson, now 95 and living in New York. “I mean, it’s not like there wasn’t plenty of activity and attention to what we were doing just a few years earlier.

“But all of that tends to be forgotten.”

Indeed, 50 years later, H. Rap Brown and the fire and riot of July 24, 1967, continue to hold a grip on the public imagination while the peaceful protests Richardson led throughout the early 1960s tend to be overlooked. It’s puzzling, because Richardson made civil rights history, openly challenging Jim Crow laws as well as the entrenched racism and poverty wrought by segregation. When she took to the streets, Cambridge’s restaurants, schools, and public facilities had yet to be integrated.

the empty lot where the richardson house once stood in cambridge; pine and cedar streets today. —Mike Morgan

Gloria left Cambridge for Howard University, where she earned a degree in sociology in 1942. She returned to Cambridge, married a local schoolteacher, and started a family. Later, she also did a stint working for the federal government. By 1961, the marriage had fallen apart, and she was working at her family’s drugstore while still living at her grandparents’ house. Richardson wasn’t yet part of the civil rights movement, though her eldest daughter, Donna, was. At the time, the lack of access and opportunity for most of the town’s black residents—living largely on the west side of the unfortunately named Race Street, Cambridge’s unofficial dividing line—led to frustration and occasional confrontations in the working class, crabbing and canning town. Only 90 miles from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., but still culturally isolated on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, Cambridge and its schools had remained segregated long after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled “separate but equal” unconstitutional in 1954. “One side of Race Street was for the whites and one side was for the blacks, and they never crossed over and we never did either,” longtime resident Sylvia Windsor told NPR during the 40th anniversary of the ’67 riot.

“The press likes to say ‘the Rap Brown riot’ and conveniently ignore everything that came before it. I mean, it’s not like there wasn’t plenty of activity and attention to what we were doing just a few years earlier.”

The students grew discouraged after a few months, when their message fell on deaf ears and their peaceful approach was met with violence. When they tried to desegregate the Choptank Inn, for instance, a protester was beaten by customers. Four of those customers were arrested by police and charged with disorderly conduct. The protester was arrested and charged with trespassing.

Gloria Richardson brushing off a National Guardsman during a demonstration in Cambridge, June 1963.

—D.C. Public Library

The local paper, The Daily Banner, was unsparing in its criticism of the protesters, whom they likened to “when cancer invades a healthy organism.” One editorial lamented that the most distressing aspect of the situation was “the white community’s loss of confidence” in its black citizens.

That spring, Richardson and her cousin’s wife traveled to SNCC's Atlanta headquarters to ask if the adults could start a group of their own. “We went down there all dressed up in our spring and summer clothes, and they looked at us like we were crazy,” recalls Richardson with a high-pitched laugh. They returned to Cambridge and, with SNCC’s blessing, formed the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC). Richardson was chosen to co-chair the group and became its spokesperson.

CNAC continued picketing the downtown business district and issued a list of demands to the mayor and city council. Mainly, CNAC wanted complete school integration, better housing conditions, the desegregation of hospitals, and better employment opportunities. Phillips Packing Company—Cambridge’s largest employer for decades—had closed down.

CNAC reached out to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to help in the effort, but were rebuffed.

Robert Kennedy and Richardson at a press conference, July 1963. —Getty Images

The setbacks strengthened Richardson’s resolve and toughened her.

“You believe your requests or demands are perfectly normal,” she says, “and when they get blocked, you become more determined to fight. It’s a process. It’s probably like men in the army. You may be scared and shaky at first, but you go on and get used to it.”

Richardson’s example stirred those around her, people like Shirley S. Jackson, who couldn’t be on the front lines at the sit-ins due to concerns she’d be singled out and fired from her job at the state hospital. Still, like many Second Ward residents, Jackson joined the larger demonstrations, contributed money when she could, and regularly attended the mass organizing meetings at a local black church. “Gloria was very vocal, and inspiring,” recalls Jackson. “I was never afraid. I always felt there was somebody looking after us, some higher power.”

The riot of 1967—a year before the rioting and unrest that would sweep Baltimore and cities across the country following the assassination of King—was not the first time race relations had burbled over in Cambridge and made national headlines. Four years earlier, at various times in the spring and summer of 1963, crowds of blacks and whites faced off in the streets, bricks and Molotov cocktails were thrown, windows were smashed, and gunshots were heard. An alarmed Richardson fired off a telegram to U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, urging immediate federal intervention. “I emphasize that violence has and most likely will occur,” wrote Richardson. “The prevailing climate is such that a state of riot could occur at any second, without warning.”

The National Guard was deployed on June 14 that year. All demonstrations were banned, and bayonet-wielding troops dispersed crowds in the Second Ward. After the Guard departed two-and-a-half weeks later, violent confrontations rocked the town again. “Negroes, Whites Try to Storm Opposite Sections of Cambridge: Guns Drawn, Bottles Thrown as Police Hold Off Mobs,” read The Sun’s headline on July 11. “At one point,” the local Cambridge paper reported, “gunshots came so frequently that it sounded like action on a battlefield.” The Guard returned July 12.

richardson in 1964. —Getty Images

President John Kennedy criticized Cambridge demonstrators, claiming they had “almost lost sight” of why they were protesting. “I think they go beyond . . . protest,” Kennedy said during a press conference. “They get into a very bad situation where you get violence, and I think the cause of advancing equal opportunity only loses.”

Not long after, actor Marlon Brando announced at a news conference that he was heading to Cambridge to join the demonstrations. The actor said he would ask Charlton Heston and Burt Lancaster to come along. (Ultimately, hospitalization from an acute kidney infection prevented Brando from traveling.)

King offered to come as well but, at that point, Richardson and others considered it “an insult,” she says, because “he was willing to come after all the national press and TV stations got in there. We were in the middle of it by then, so we said, ‘No thanks, we can handle it ourselves.’”

Eventually in that summer of ’63, Richardson met with Robert Kennedy in Washington to hammer out an agreement to address CNAC demands and diffuse the situation. The nine-hour negotiating session included Cambridge leaders, Justice Department officials, and activists such as SNCC chairman John Lewis. The agreement called for a biracial Human Relations Commission in Cambridge, desegregation of the first four grades of Dorchester County schools, federal housing assistance, better consideration for blacks for state jobs, and a charter amendment to desegregate public accommodations. The agreement, which also called for a halt to demonstrations, noted that the amendment, which was expected to go into effect the following month, could be subject to a referendum. It was also noted that all the signers hoped to avoid putting it to a vote.

Kennedy chided Richardson for being so serious. “Do you know how to smile?” he asked at one point, getting a barely perceptible smile in return. Richardson declined to declare victory, preferring instead to characterize the agreement as “an initial step” toward progress. “Gloria felt no sense of relief, no sense of happiness or joy,” Lewis recollected in his autobiography, Walking With the Wind. “It was written all over her face.”

Bethel A.M.E. Church. —Mike Morgan

As it turned out, her caution was warranted. The Dorchester Business and Citizens Association (DBCA), a pro-segregation group claiming hundreds of members, spearheaded an effort to force a vote to repeal the public accommodations amendment. In the run-up to the October vote, the DBCA took out newspaper ads asking, “What’s wrong with a businessman selecting his customers?” and concluding:

There is nothing morally wrong about it. There is nothing legally wrong about it. So . . . let’s keep it that way.

The DBCA urged whites to vote against the amendment.

Richardson, surprisingly, urged blacks to boycott the vote. “I remember thinking, ‘Why should voters decide whether we can go into a restaurant or not?’” says Richardson, who was honored during a Tribute to Negro Women Fighters for Freedom at the March on Washington. Though Richardson’s position disillusioned some blacks, she was a firm believer that “basic human rights should not be put up to a vote.”

The amendment was defeated.

Over the next year, Richardson and CNAC continued pressing for those rights and enlisted the likes of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, and Louis Farrakhan, who all made appearances in Cambridge. Richardson also met Malcolm X in Detroit—where his landmark “Message to the Grassroots” speech included a shout out to her—and they became allies. She invited him to Cambridge and planned to accompany him on a trip to Africa, where, he told her, people had asked him about the Cambridge movement during a previous visit.

In May of 1964, the DBCA, looking to counter CNAC’s momentum, brought George Wallace to town. The notoriously racist Alabama governor drew a vocal crowd of 2,500 to the Rescue Fire Company (RFC) arena, where his 50-minute speech was reportedly interrupted 48 times by applause.

the only remaining wall of the Pine Street School. —Mike Morgan

The DBCA’s efforts ultimately proved futile, as boycotts of downtown businesses continued. In July, the Dorset Theater was finally desegregated, and activists set their sights on the RFC pool. That same month, the City Council named Charles Cornish its first black president. Tangible progress was being made, and the National Guard left town that summer after more than a year patrolling the streets.

Then, Richardson left town, too. She had met and fallen in love with Frank Dandridge, a Life magazine photographer on assignment in Cambridge. Richardson and Dandridge married and then moved to New York, where she worked as a program officer for the city’s Department of Aging. “We had, by that time, achieved some things,” says Richardson. “It seemed like it was a community effort that could be carried on.”

Two years later, she followed in horror the news accounts of Cambridge burning.

In the wake of the ’67 fire, Cambridge changed profoundly over the next half-century. Great strides have been made in terms of desegregation, racial relations, and access to schools and jobs, which isn’t to say the town has overcome all of its problems. The Second Ward is still battling poverty and high unemployment; like a lot of places, it remains segregated along economic lines. But if anyone fully embodies the change in Cambridge, it is Victoria Jackson-Stanley. The town’s first black mayor, Jackson-Stanley is serving her third term at City Hall. Her father, Frederick Douglass Jackson Jr., worked closely with Richardson.

“If she was the general, he was her lieutenant,” says Jackson-Stanley. “I’m sure there were others, but when the National Guard was there with the bayonets, he had her back.”

As a little girl, Jackson-Stanley idolized Richardson. “I remember looking up at Gloria Richardson and thinking she was the most beautiful and powerful woman I’d ever seen,” the mayor recalls. “She had a presence about her, and I was in awe of her. Harriet Tubman and Gloria Richardson have been my idols since I can remember. They set the path for me.”

Cambridge mayor victoria jackson-stanley, who idolized Gloria Richardson as a girl. —Mike Morgan

Jackson-Stanley acknowledges that economic growth and affordable housing remain serious issues, before ticking off a list of recent developments: the opening of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historic Park, a planned mixed-use rehabilitation of the old Phillips factory, growth in the downtown retail district, two medical marijuana growers and processors coming to the county, and various beautification projects happening along routes into town.

“We look better, and we’re moving in a positive direction,” says Jackson-Stanley, who expresses frustration that many people know nothing about Cambridge beyond its H. Rap Brown connection. “There is a lot more history here, especially history that reflects the power of strong, black women.”

“We look better, and we’re moving in a positive direction. There is a lot more history here, especially history that reflects the power of strong, black women.”

Dion Banks sees something similar. A Cambridge native who returned to town after serving in the military and living in Chicago, Banks co-founded the nonprofit Eastern Shore Network for Change (ESNC) with local attorney Kisha Petticolas in 2012. Their offices are located in the Pine Street police substation, just steps from where Brown delivered his infamous speech.

“Gloria Richardson is a personal hero of mine, and it blows my mind she hasn’t been celebrated more,” says Banks, before pointing out that this is slowly changing. “These days, she’s finally getting talked about in schools and in churches, and she’s being associated with Harriet Tubman, which makes sense.”

ESNC—whose mission is to “inform, educate, and foster change that leads to social and economic empowerment” in Dorchester County—sells T-shirts emblazoned with the names “Tubman Richardson Jackson Stanley” to raise money. The shirt includes an inscription: “Because the status quo is not an option.”

Kisha Petticolas and dion banks, co-founders of the Eastern Shore Network for change. —Mike Morgan

“ESNC challenges people to have open-ended conversations about various issues and topics, including race, ” says Banks. “Then, we work collectively to create solutions that tie in existing resources. If those resources don’t exist, we try to create them.”

With the 50th anniversary of the riot approaching, ESNC set out to reclaim and tell the community’s story from that era. It partnered with radio station WHCP to record memories of the local movement, not just the fire. The group is also sponsoring commemorative Reflections on Pine events from July 20-23 that include a prayer breakfast, art exhibit, street festival, and community conversation on race. (Her health permitting, Richardson plans to attend.)

“We have our issues, but we’re working through them,” says Banks. “We are actually a progressive community, a loving community, and we want people to see us in that light. I feel like it’s my responsibility to embody these things for a new generation. It’s a continuum, the same fight but a different time period with different tools.”

With that, Banks gets up from his chair, steps outside, and points out a gray cinder block wall behind the substation. It’s an original wall from the burned Pine Street School, which, notes Banks, both of his parents attended.

It’s also a reminder of the town’s segregated past. “That’s the beginning and the end right there,” he says, blinking in the bright sun. Then, he turns away and gets back to work.