While incarcerated for six years on drug charges, Jesse Krimes made art—through very limited means—to transcend his environment and ultimately find a sort of freedom. The first pieces the Philadelphia artist constructed behind bars were newspaper mugshots of offenders transferred onto prison-issued bars of soap. He made them during the full year he spent in solitary confinement, awaiting trial, and called the series Purgatory.

Once sentenced and moved to a prison in North Carolina, he smuggled bedsheets into his cell and transferred images from The New York Times onto them with hair gel and a spoon, often using the same mugshot imagery but substituting criminals’ faces with those of politicians and other social icons, with the mindset that “we’re all offenders,” as he puts it. He mailed home each completed sheet (quite an undertaking, as he was not supposed to have them and had to disguise the parcels), with the intention to combine them all into one massive mural upon his release in 2013—which he did.

The resulting piece spans 15 by 40 feet, with three long horizontal rows of sheets pinned together. He calls it Apokaluptein:16389067 and has shown a scaled-down replica of it in a handful of galleries since his release. It’s currently at Julio Fine Arts Gallery at Loyola University Maryland through February 28. Though he includes other work in the Baltimore show, the title piece is perhaps his most impressive, spanning the length of one wall of the gallery and busier and more colorful than the other work.

Though the aesthetics, execution, and details are worth hours of viewing pleasure in and of themselves—Krimes earned a BA in studio art from Millersville University just prior to his arrest—the images are also layered heavy with meaning, worthy of many more hours of viewing and thought. Krimes doesn’t shy away from symbolism and the use of popular culture, political icons, and the historical events that took place while he was behind bars to shed light on the issues at play in modern times and his perspective on them. He considers himself a conceptual artist, first and foremost, and notes that he pays close attention to the materials he uses and the language that’s invested in them.

As much as Apokaluptein:16389067 appears to be a statement on American culture, it can also be interpreted as the image of a human’s internal workings—a mental or spiritual landscape. It could also be read as a modern retelling of Hieronymus Bosch’s famous “Garden of Earthly Delights” triptych. But rather than showing a sequence of time in linear fashion, as Bosch did, Krimes’ narrative arc appears to be a vertical path—either dropping down into consumerism and false projection of self or rising toward a pure reflection of the self as seen in its natural state. The images are much lighter on the top row, almost as if this row above is an angelic realm whose small, flying women, affixed with rectangular mugshot heads, are colored a sharp white. Below them, in the middle layer, similar female figures drawn by Krimes are colored a fleshy peach, and in the bottom panel, they are faceless line drawings.

In its totality, Apokaluptein:16389067 (its title is the Greek origin of the word apocalypse, followed by Krimes’ Federal Bureau of Prisons inmate identification number) contains nearly every historical event from 2010 through 2013, when it was made. Reading the Times “was the only way to experience the world,” Krimes says. “I think what really saved me was the [art]work and reading.”

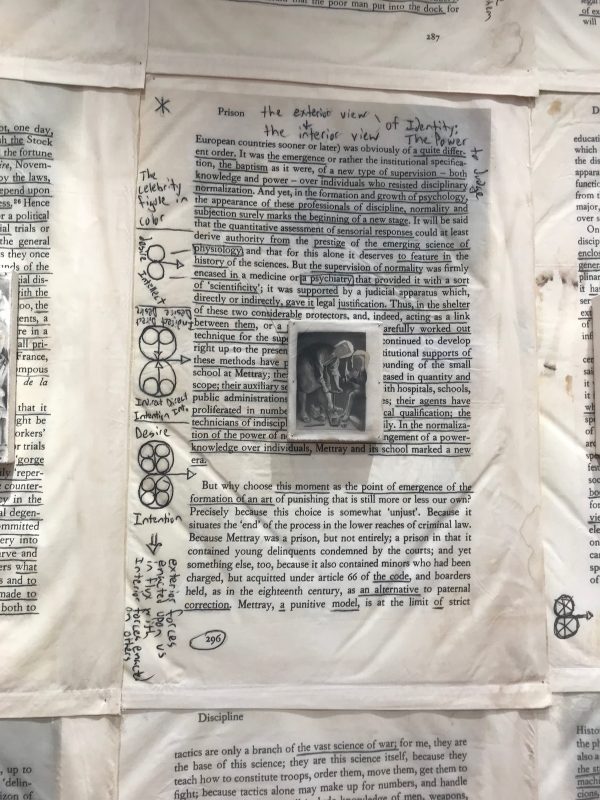

Along with the Times, he was reading The Kingdom and the Glory by Giorgio Agamben and Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, the latter of which worked its way into his pieces in a very literal sense. He hand-transferred digital prints of pages of text from Foucault’s book—marked up with his annotations made while incarcerated—onto prison bedsheets dyed with coffee, giving them an old book quality.

Nearly all the pieces include his trademark treatment of mugshots: rectangular cutouts of politician and celebrity headshots (there are quite a few of Lindsay Lohan and Paris Hilton, who were in the news a lot at the time) layered onto other bodies. Krimes uses this specific treatment to convey a message. Instead of the government showcasing its power through public beheadings, they now put mugshots in newspapers, he points out. A head against a solid backdrop gives no context, while the text surrounding that image describes a person during one specific moment in time and often says little about who they really are—or who they were or who they’ll become.

Since his release, he’s worked, primarily through art, to bring awareness about mass incarceration and the injustices faced by prisoners. It should be noted here that Krimes saw firsthand how charges can be manipulated. He was caught with 140 grams of cocaine, but the drug weight—and therefore his charge—was increased to 50 kilos when he wouldn’t “cooperate,” he says, and rat out others involved. The weight increase was based on hearsay. He was sent to a maximum security prison, where the nonviolent offender shared space with serial killers.

“Everyone has been touched by this [mass incarceration] in some way . . . but people don’t talk about it,” he says.

He’s exhibited his work and given talks at multiple galleries while continuing to make more pieces and experiment with different mediums (his work is in the group show Prison Nation at Aperture Gallery in New York through March 7). He gave a TEDx Talk in 2015 in Philadelphia about prison. In 2017, he was named an Artist as Activist Fellow through the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

As part of his fellowship, he’s bringing art to rural places around Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to expose people who might not normally attend an exhibit. For an upcoming project, he’ll install art in a barn inside a corn maze. And that art will in turn become a catalyst for talking about our federal prison system, which is, as he sees it, a microcosm of American society.

“Incarceration is more common than you’d think, but I go into communities that have no clue about it. . . . You think slavery’s over? It’s not.” Instead of picking cotton, he says, inmates are paid ridiculously low wages to make desks and chairs and bed sheets.