Arts & Culture

Her Own Brush

Exhibit at Reginald F. Lewis Museum explores an artist ahead of her time.

The line of cars rumbles down a long road, covered in pine needles and shaded by towering trees, before stopping at a magnificent brick mansion with walls blanketed in ivy. Here, seven passengers alight and follow a regal, blond woman inside. She hustles them through the drawing room and a library lined with wood bookcases, then outside onto a wide porch with a breathtaking view of lapping water leading to the Chesapeake Bay. “Oh wow, look at that,” one woman murmurs. Cicadas hum in the July heat and the fragrance of mint from the garden fills the air as the guests sit in wicker chairs.

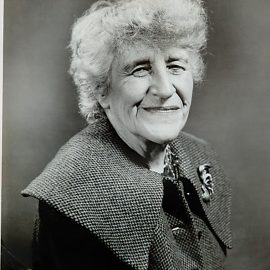

The group—which includes the former chair of the Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture and an expert in African-American spirituals—has come to tour Hope House, a plantation just outside Easton on the Eastern Shore. The attraction is the home’s former resident, Ruth Starr Rose, a talented, yet little-known artist whose work is the subject of a major exhibition at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum. It may seem odd for a museum dedicated to African-American culture to show work from a privileged, white woman, but Rose was always doing the unexpected. For subjects, she chose the African-American members of the Easton community—unheard of in the early 20th century.

“See that boat across the water?” Barbara Paca, the woman leading the tour, asks, pointing to a slip of land that appears over the narrow creek. “That was Ruth Starr Rose’s dock. She had her studio over there.”

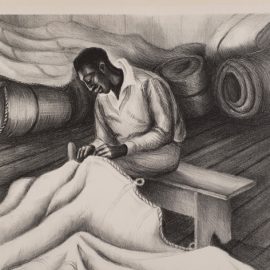

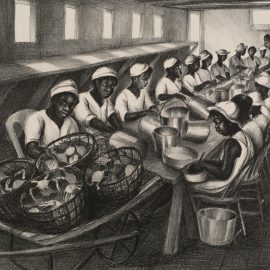

Paca, a noted art historian and creative designer, curated the exhibit of Rose’s work, Ruth Starr Rose: Revelations of African American Life In Maryland and the World. It features portraits of crab pickers, sail makers, and heroic soldiers, some of whom were descendants of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, as well as bold depictions of spirituals. Rose captured those she called “her beautiful people” with an elegance and pride during an era of intense segregation and Jim Crow laws.

Her radical views could explain why she is not listed among other groundbreaking artists of her time. But Paca’s exhibit, which opened in October, aims to shed light on this unprecedented artist that history forgot.

“She gave strength to so many different people,” Paca says. “Ruth didn’t want to make the world more confused, she wanted to show universal brotherhood, to bring about a unity in races through paint.”

The exhibit coincides with the Lewis Museum’s 10th anniversary and is the first comprehensive showing of Rose’s work. “I’m overwhelmed with the similarities in tension between the time Rose lived and the atmosphere around civil rights now,” says the museum’s executive director A. Skipp Sanders. “This is an important story, and a perfect example of how art can capture history.”

Though Rose received accolades during her lifetime—with shows in Europe and New York and works in collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian—critical acclaim eluded her.

“When her work is most compelling is when she was doing what she wanted to do.”

Keith Sheridan, an art dealer based in Myrtle Beach, SC, who sells Rose’s prints, said she put the male-dominated art world on edge. “She’s left out more because of her subject matter and style, which wasn’t something the art world recognized as progressive.”

To this day, Paca says, “male curators use terms like ‘saccharine’ to define her work, or ‘amateur,’ or ‘socialite.’” But she and others see Rose’s work differently. “There’s no doubt this woman is a first-class artist, and that she is every bit as good as her male counterparts. She was just shoved aside,” Paca says.

“There’s no pretense to her work,” Sheridan says. “She portrays these social issues in a format that’s heart-felt and natural.”

Though it took over 10 years to find support for the exhibit and gather Rose’s prints and paintings, their beauty and power has transfixed art patrons. And that has affirmed Paca’s belief that Rose’s story has a message that still needs to be heard.

It was 1906 and Rose was 16 when she and her family moved to Talbot County from Eau Claire, WI. The Starrs had purchased and refurbished the run-down, 17th-century plantation called Hope House, and set about constructing a lifestyle vastly different from their neighbors—one of equal dealings between blacks and whites.

William Starr had made a fortune in timber—he brought the wood for Hope House’s library bookcases from one of his mills. His family had been active abolitionists in Wisconsin, and while at Hope House, he and his wife, Ida May Hill Starr, entertained black guests as well as prestigious visitors such as President Woodrow Wilson, and brought black friends to the nearby country club. Ida May highlighted the work of African-American gardeners while writing for fashionable publications.

“These people were ahead of their time,” Paca says. “They had an integrated community here, and it made people very uncomfortable.”

Rose attended Vassar College, then enrolled in classes at the Art Students League of New York. In 1914, she married William Searls Rose, who was also from a wealthy family, and they settled outside New York City, and adopted two children. But they spent summers at Hope House, and at the adjoining farm, Pickbourne, which had been Rose’s wedding gift. Her wealth allowed her to pursue art, and the social activism she valued.

On the Eastern Shore, she raced log canoes, taught Sunday school in Copperville, and brought prestigious friends to visit, including author DuBose Heyward, best known for his novel that was adapted into the opera Porgy and Bess, and artist Prentiss Taylor, famed for his lithographs of Harlem life.

“She did everything in capital letters,” says granddaughter Brenda Rose. “She was not traditional by any means.”

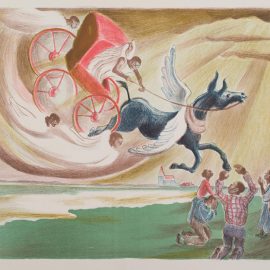

Rose painted and sketched the people around her, in their homes and at work on the water, using bold colors and brushstrokes reminiscent of contemporaries Thomas Hart Benton and Georgia O’Keeffe. She illustrated the historic songs passed down through generations of slaves, depicting fiery flames and parting seas. Hers were the most comprehensive visual interpretations of spirituals in the United States, said noted Howard University professor James Amos Porter in 1956.

Critics didn’t know how to react. Rose was lauded for her technique, but cautioned to stick to paintings of boats and flowers. But she was not swayed.

“She wanted people to learn that we are all part of the color palette,” Brenda Rose says. “She wanted everyone to see that we are just people.”

Still, Rose seemed to understand that she was only one person, that it would take a movement for any real change to occur.

“Instead of a story of wonders, I can only tell you about the very insignificant struggle of one human being against a world of ignorance and hate,” she wrote in a 1930 speech. “The very little I have been able to do is only the smallest dent in the steel wall of the caste system.”

Rose demonstrated the courage of her convictions, particularly in 1933 when she had the only solo show of her life in Baltimore at the Municipal Arts Society. This was shortly after a lynching on the Eastern Shore led to the National Guard being dispatched near Hope House to control angry white mobs that protected four of the assailants. Reviewers of the show incorrectly spelled Rose’s name—but Paca believes that was on purpose, to protect her.

The Great Depression brought hardships, and the family eventually sold Hope House. After her husband’s death, Rose left Maryland, traveling and staying at her ranch in Montana, before settling in Alexandria, VA, where she died in 1965. She added cowboys and cherry blossoms to her repertoire, and painted Haitians and members of the Seminole tribe. But her later work didn’t seem to have the same connection as with her Easton subjects.

“When her work is most compelling,” Paca says, “is when she was doing what she wanted to do. It’s almost like she was filling in the blanks, saying, ‘We all know what George Washington looked like. Here are the people you don’t hear about.’”

This idea of a shared history, regardless of race, is something Paca believes firmly. She is dismayed when people ignore a story or key fact because it’s complicated, or makes them uncomfortable.

Though she was born in California, and now spends most of her time in New York, Paca has family ties on the Eastern Shore, and is drawn to the place and its history. Still, she wasn’t prepared when she discovered Rose’s painting of a young woman with creamy, caramel skin and a peach hair ribbon at a Chestertown art restoration studio some 10 years ago. She was further astounded when conservator Kenneth Milton told her the artist was a white woman, not an African-American. Paca left the studio with the painting—which some now call the “Black Mona Lisa”—and a desire to find out more about Rose.

Paca encountered apprehension when she began asking her relatives, who lived close to Hope House, about Rose and the Starrs. They hastily replied, “We don’t want to talk about it,” and it reminded Paca of another time she’d received a similar response. Her family is descended from William Paca, one of Maryland’s founding fathers and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The family always knew he’d had an illegitimate daughter of mixed race who’d vanished from historical records and was rarely, if ever, spoken of. “I always felt badly that we didn’t know that story,” Paca says. “And there were many people in my family who were very uncomfortable with my constant asking of that question.”

As she interviewed the descendants of Rose’s portrait subjects, many of whom still live in the towns of Copperville and Unionville, they told her how much they wanted their story told. Paca knew she would follow their wishes. The exhibit is scheduled to tour Maryland after its Lewis Museum run.

“I’m so impressed that there are paintings that show the black community as a proud and dignified community,” says Jeffrey Moaney, who grew up on the Eastern Shore and whose ancestors Rose portrayed. “It’s important that our part of the history is shared just as the white history has been.”

After the Hope House tour that July day, Paca gathers the guests back into the cars—they’re headed up the road to Wye House, the plantation where Frederick Douglass had been enslaved. A mission of the trip is to gather anecdotes for the exhibit, so Paca guides Tissier Moaney, Jeffrey Moaney’s grandmother and a descendant of Wye House slaves, to the high-ceilinged veranda where the lady of the house once sat.

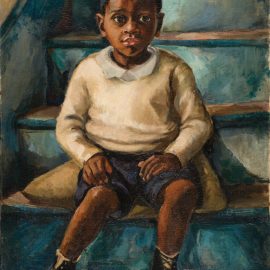

A Lewis Museum staff member takes out a video recorder and asks, “How do you feel when you see Ruth Starr Rose’s portraits?” Rose had painted Moaney’s husband as a chubby-cheeked infant.

Moaney, 83, thinks for a moment, then replies, “Her portraits represented [our] honor and strength.”

After more questions, a group member asks if Moaney, a singer and pianist who has received commendation from President Barack Obama, wants to sing a spiritual.

“How about ‘Ride On King Jesus’?” another visitor asks.

“Get it started,” Paca instructs, and soon Moaney and others sing in harmony, “Ride on King Jesus, no man can a-hinder me.”

Paca watches, and thinks to herself, “Ruth would have liked to see this.”

Big Ten

The Reginald F. Lewis Museum opened 10 years ago with a mission to preserve and educate the public about Maryland’s African-American culture. Here’s a timeline of the museum’s history:

June 25, 2005: The Reginald F. Lewis Museum opens. Its first exhibit is A Slave Ship Speaks: The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie. February 2007: The exhibit At Freedom’s Door: Challenging Slavery in Maryland debuts, the state’s first large-scale exhibition to focus on slavery and its aftereffects.

Fall 2013: Facing declining attendance and revenue, the museum drafts a plan to rebound.

December 2013: Maulana Karenga, the founder of Kwanzaa and a Maryland native, speaks at the museum’s annual Kwanzaa celebration.

May 2014: USA Today calls For Whom It Stands: The Flag and the American People one of the summer’s must-see exhibits.

July-August 2015: The free Lewis Now space opens with an exhibit by photographer Devin Allen, whose work appeared on the cover of Time following the death of Freddie Gray. Misty Copeland speaks to a crowd of 1,000 on the day that she becomes American Ballet Theatre’s first African-American principal dancer.