The artist-run spots that are changing the art

scene—and why you should experience them now.

The artist-run spots that are changing the art scene—and why you should experience them now.

When we think about where to go to experience art—whether browsing an exhibit, soaking up a live musical performance, or trying out our own skills in a class—a few places probably come to mind. Museums like The Baltimore Museum of Art or The Walters Art Museum. Theaters like Center Stage and the Hippodrome, or concert venues like Rams Head Live and the Royal Farms Arena. But what if you put all of those facets of the art scene, albeit on a smaller scale, under one roof? That’s what the spaces we feature in this year’s fall arts feature are all about—combining artistic genres in a way that promotes collaboration, builds community, and accelerates artistic growth. “You can find artist-run art spaces across the country and world, but I think Baltimore has a real knack for growing and incubating them,” says Ryan Patterson, public arts administrator for the Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts (BOPA). “Everybody is on a similar wavelength of wanting to see success for one another, and they’ve built a really great ecosystem around each other. The soil’s the right condition to let these spaces grow.” That “we’re all in this together” spirit has also defined the overall arts community here in Baltimore. “For years, we’ve been identified as a DIY scene, but I think that’s a misnomer,” says Marcus Civin, associate dean of graduate studies at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and an interdisciplinary artist himself.

“We’re more like a ‘do it together’ kind of community—DIT. Does that sound good?” he says with a laugh.

Plenty of parts have come together to allow these spaces to thrive. For one, art programs at MICA, Towson University, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, as well as others, continually release talented, enthusiastic young artists onto the scene. Affordable studios and warehouses give creative types a place to continue their craft. Artist grants and financial resources through organizations—including BOPA, the Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance, and The Contemporary—demonstrate how much our community cares about arts and culture, and our three designated arts and entertainment districts provide support and backing for the scene. But the events of the last year, especially pertaining to the death of Freddie Gray, have added extra urgency and zeal to artistic endeavors.

“The Baltimore Uprising had a huge impact,” Civin says. “African-American artists have used art to deal with the pain surrounding last year’s events, but some artists who aren’t of color have also taken strides to become accomplices in diversifying what we see and what we do.”

At the spaces we’re featuring here, and at dozens of others across Baltimore, you can see (or soon will see, in the case of Le Mondo) some of the most exciting, thought-provoking, groundbreaking work the city has to offer—from the freshest, experimental performance and video art to work by established, renowned photographers and painters who remain committed to the city, and to its “DIT” spirit.

“There’s even more of a collective spirit, more of a can-do energy right now. I’m optimistic it will only get better,” Civin says. “And you should

see it now. You want to get in on the ground floor, right?”

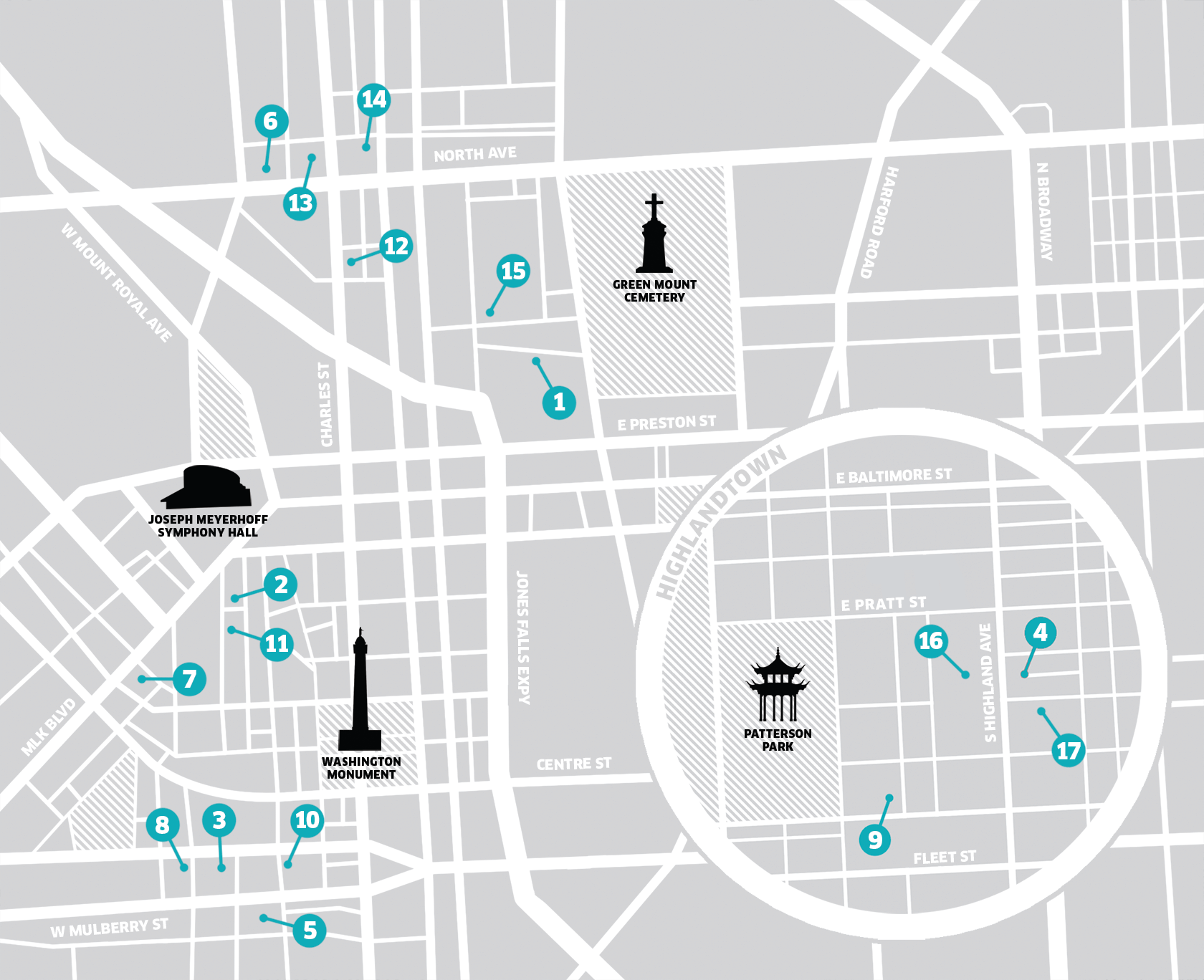

1. Area 405 405 E. Oliver St.

2. Pipe Dreamz 879 N. Howard St.

3. Le Mondo 404-406, 408-412 N. Howard St.

4. Y:ART 3402 Gough St.

5. Terrault 218 W. Saratoga St.

6. Motor House 120 W. North Ave.

7. Arena Players 801 McCulloh St.

8. H&H Building 405 W. Franklin St.

9. Creative Alliance 3134 Eastern Ave. 10. Platform Gallery 116 W. Mulberry St.

11. Eubie Blake Center 847 N. Howard St.

12. Metro Gallery 1700 N. Charles St.

13. Space Camp 16 W. North Ave.

14. Centre Theatre 10 E. North Ave.

15. La Bodega Gallery 1501 Guilford Ave., A100

16. Schiavone Fine Art 244 S. Highland Ave.

17. Highlandtown Gallery 248 S. Conkling St.

Area 405

405 E. Oliver St.

The ground floor of this 66,000-square-foot warehouse in the Greenmount West neighborhood is cavernous, with thick steel beams that stand guard between the exposed brick and wood plank floor. But all it takes is an art opening, theater performance, lecture, or wedding for the space to come alive, inviting laughter and shared connections to ring off the beams, and for a community to come together.

In many ways, Area 405 is the godmother of Baltimore’s multidisciplinary art spaces. Fourteen years ago, few people thought to incorporate different artistic aspects under one roof, but Stewart Watson did—though that might not have been the initial idea. The Baltimore artist and her husband, fellow artist Jim Vose, began looking for a place to live and also have studios, but met with resistance from banks and mortgage lenders, as well as from friends and other artists.

“We could see things in these buildings that others couldn’t,” Watson says. “And I think being naive was somehow an asset, and people telling me I couldn’t

do it probably made me more resilient. I certainly didn’t know how much this was going to mean to anybody else. I thought it would be a space for us and

then I might have a gallery. How could I have anticipated all of this?”

▶Stewart Watson inside Area 405 with her Great Danes Nigel and Ada.

On this quiet May morning, Watson has appeared, mirage-like, in a doorway, accompanied by one of her gargantuan Great Danes. (Today, it’s Ada. Nigel is upstairs.) Wearing a full-skirted black dress and funky black heels, with her hair in a bun, she walks into a spot where light pours in from a row of windows.

“This is the space that really made me want to buy the building,” she says. “Then, it was completely filled with stuff—piles of trash and machines. All of the back windows were bricked in. We’ve filled over 160 dumpsters.” Watson stops as the crash of metal clangs from a nearby work station. “That’s actually pretty quiet around here,” she says with a knowing smile.

This former venetian blind factory obviously needed work to be rehabbed (work that was literally back breaking for Watson, who herniated several discs and had to have spine surgery). Because of the building’s size, and the money required in order for Vose, Watson, and three other owners to get it into shape, they decided to rent out some of the space to other artists. Serendipitously, its beginning coincided with the designation of the Station North Arts & Entertainment District in 2002, which brought a fervor to the arts scene, and a need for a place where people could collaborate and build community.

Area 405—named for its address—opened in February 2003. The second-floor Oliver Street Studios provides working space to more than 40 artists, and the adjacent Station North Tool Library offers equipment rentals and workshops. So far, the complex has welcomed hundreds of thousands of visitors.

And, Watson and Vose got their wish for a home—they share the third floor with their young son. “I never would have thought I’d make a place that was so important and valuable to Baltimore,” says Watson, “where my kid gets to run around as we connect all varieties of people.”

Spacemakers

Baltimore’s art scene has been defined by creatives who have made their own spaces—not always in the conventional sense—where they display work and further community conversation. In their own words, four such artistic ambassadors describe their missions.

Click the circles above to learn more.

Pipe Dreamz

4879 N.Howard St..

Like Stewart Watson and Jim Vose, Ansar Miller-Abdullah didn’t set out to create an art space. When he spotted the white bay window of the Howard Street storefront across from the University of Maryland hospital, he was thinking only of starting a fashion boutique that would feature a few hip-hop events. After renting the space, it wasn’t until he met the young artist Saadiq Tafari that he realized the walls had value. “He brought down his pieces and had an art show the week before we opened [in September 2015], and people loved it. It was packed. And from that, other people walked in, asking, ‘How do I get my art up here?’” says Miller-Abdullah, who goes simply by AC, a nickname that harks back to his hometown of Atlantic City, New Jersey. “I really didn’t know anything about how to sell art. I just thought, ‘Hey, I have the space, why not help people?’”

From there, AC says, “it was a snowball effect.” People flocked to the spot and mentioned their own creativity. Many were rappers and spoken-word artists.

“Some were in and out of trouble, and jail, but they had talent,” says AC. “To keep them occupied and off the street, I said, ‘Come down to the shop and

practice.’” That led to monthly showcases, which AC dubbed the Pipeline Series, that today pack more than 100 people into the 1,000-square-foot space.

▶a Pipe Dreamz hip-hop showcase.

At one such event in June, young people of all colors—and an average age of about 20—spill out of the space, their energy lingering on the street. Inside, rappers spit rhymes into a mic, surrounded by a crowd whose bodies rock to the beat, as Chuck Taylors thump on the wood floor and sweat glistens on their arms. From time to time, attendees take Sharpies to a wall to sign their names, a gesture AC requires of all his patrons.

Each day, as he sits outside Pipe Dreamz’s front door and plays chess, AC sees the positive effects his establishment has had on the block (which also includes the Eubie Blake National Jazz and Cultural Center). When it first opened, he witnessed drug activity and prostitution, and heard about robberies. But now, “there’s literally been no crime on this street. It’s something about the shop, what we’re doing here, that makes everybody respect the community.”

Owner AC outside his shop.

He realizes, too, that there is something deeper driving the creativity. After the death last year of Freddie Gray, and the ensuing unrest, AC noticed more people turning to artistic expression to work through the emotions they felt—which he’d done himself growing up. “My house was considered the crack house. What I used to do to escape the horrors going on was sit down and write, from the time I was 3 years old. I was going to go off to distant lands and beautiful castles. I was dreaming beyond my surroundings.”

That was the genesis of the space’s name, he says. “Whatever is going on outside that door, whether it be drugs, crime, or social injustices, when you come in here, you can shed all that hopelessness. All your dreams or wants or desires, we can try to obtain them.”

He hopes to inspire similar spaces, too. “I want somebody to open something like this in West or East Baltimore or Park Heights or Greenmount, or Cherry Hill—the places that really need it,” says AC. “If you have hubs where people can build and grow, then you are slowly but surely changing the city.”

Le Mondo

404-406, 408-412 N. Howard St

The row of apparently dormant buildings that sit west of the light rail tracks on Howard Street, amid bright murals and boarded-up structures in what was once the city’s bustling commercial and theater district, tends to attract attention when one of the building’s gray, metal grates is suddenly raised up over the windows.

That’s what has occurred this July day, as Le Mondo’s trio of founders opens up one of three spaces they hope to renovate. In this first one, where ladders, tarps, and the smell of freshly cut wood indicate that work has begun, co-founder Carly Bales is discussing the newest addition, an antique bar, when a curious passerby pushes open the door and asks, “What is this place?”

Without missing a beat, co-founder Evan Moritz replies, “It’s a theater, performance venue, bar, and art education spot.”

“Huh,” the man says looking around. Then, “do you need any construction help?”

Moritz looks toward Le Mondo’s third co-founder, Ric Royer, who is heading up the build out. “Get his information,” Royer says, reaching for a piece of

paper. It’s obvious he’s used to this.

▶ Le Mondo co-founders evan Moritz, carly Bales, and ric Royer.

Since the deal that conceived Le Mondo was announced two years ago, there’s been plenty of buzz surrounding it, and for good reason. When the $6-million project comes to fruition in the next few years, it will transform a block of Howard Street and, the founders hope, return the ornate structures to what they were in their heyday.

“It was so serendipitous when the city asked for proposals for these buildings, because basically it was the same exact block we’d been talking about for years,” Bales says. “We thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if the old vaudeville district had these new-wave performance venues?’ There’s a certain energy and history to Howard Street that’s palpable, even today amongst a lot of decay and disinvestment.”

The idea for Le Mondo originated in 2013, when the heads of several smaller arts organizations held roundtable discussions to address the lack of artistic space and to iron out what it would look like if they pooled their resources to purchase buildings that would become venues and studios. Bales, Royer, and Moritz—who head up the arts organizations EMP Collective, Psychic Readings, and Annex Theater, respectively—became the leaders of the effort, which came to fruition when the city began looking for development ideas for a portion of Howard.

Plans have changed slightly as one of the original three buildings burned partially to the ground, but the group ended up buying an adjoining structure that was in better condition, which will be the first space to open, likely early next year. Construction and fundraising for Le Mondo have been extremely grassroots, with much of it coming by way of volunteers, but the founders hope to have all three structures up and running by 2020.

Some surprising newly discovered historical information has added to their motivation. The first space that will open served as a vaudeville theater in the 1920s and 1930s, and one of the other buildings was a famous German restaurant where H.L. Mencken played in a jazz band and actor Henry Fonda held one of his wedding receptions.

They try to keep the hard work in perspective. “It’s a long investment of time, but I’ve spent more time shuffling between spaces and making makeshift light grids because we didn’t have our own building,” Moritz says. “This is a really long project, but at the end is a really big reward.”

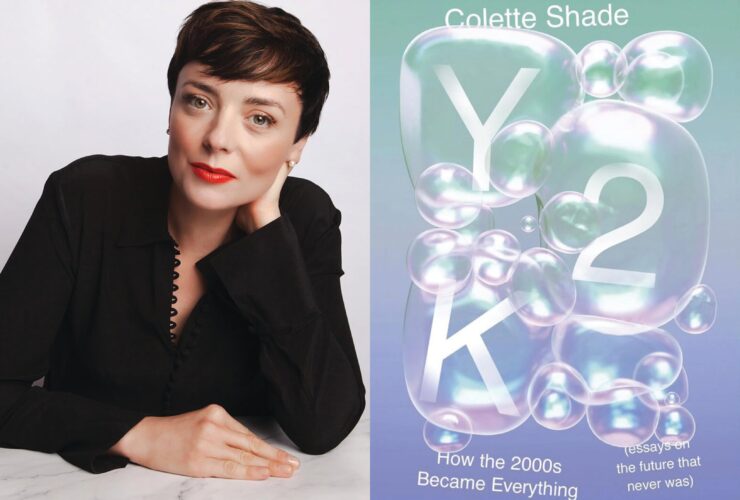

Y:Art

3402 Gough St.

Juli Yensho strolls among the art in her gallery, introducing each artist like an old friend. In some cases, they are—Yensho herself is an artist and a

Baltimore native, who has decades of experience in the art world (including time spent as a scenic painter on the sets of Baltimore-filmed TV shows Veep and House of Cards). Her own ceramics and painted rugs are among the pieces adorning the walls and shelves in her space’s three

rooms in Highlandtown. “I always feature a sculptor, and this is David Hubbard,” she says, pausing at a twisting, stainless steel form standing on the

floor. “And this is Ben Eiben’s work, a living wall,” she says, pointing to blooming plants that create a design within a frame. “It’s magnificent, and I

think of it as my foster child. I may buy it from him.”

▶ A Friday evening rug painting class at Y:Art.

Yensho and her husband, Tom, discovered the Formstone and brick-fronted space in 2010 while walking their dogs (they lived a few streets over at the time). It had been a Sons of Italy lodge (it sported the enormous wall decals of Sicily to prove it), and then a car dealership. The Yenshos were taken by its quirkiness and potential, and made an offer that day to the building’s owner, who happened to live across the street.

Their purpose became clear as the Yenshos rehabbed the space and discovered what it was capable of. The former lodge’s bar was intact—perfect for community gatherings—and it had room to install a storefront. Plus, its time as an auto dealership had left plenty of space in the back for studios. It took a few years to come together, but in December 2013, the space held its first show—a holiday mart—and it officially opened this past October.

Since April of last year, Juli Yensho has had to go it alone, as Tom passed away after years of illness. “He was so good to me,” she says. “If anyone ever believed in me, it was Tom.” But she is comforted that he is still a presence at the gallery—his remains are encased in an urn she made that sits overlooking the bar so he can watch over his wife, and their creation.

juli Yensho and some of her wares.

So far, Y:ART has held six shows, and has three more planned, including the first exhibit in 13 years of the work of noted photographer and MICA professor Connie Imboden. The gallery features fine art workshops and paint-your-own-rug nights—during which Yensho instructs bustling groups of wine-drinking art enthusiasts on the finer points of design and brushwork—plus a shop that showcases jewelry and furniture by local artisans. In the future, she’d like to add more artists as workshop instructors and make the space available for event rentals as well.

“I love art, and I’ve known a lot of artists, and I’ve gotten to know a lot more doing this. It’s been an adventure—I’m just kind of making it up as I go along,” Yensho says. “I don’t take myself too seriously, I just do it. I curate all the shows and I choose all the artists. And so far, so good.”

WHERE THE

MAGIC HAPPENS

The idea of trying something new might sound appealing, but when you’re standing in the doorway of an unfamiliar building, surrounded by unfamiliar people, you start to question your decision. Breaking out of our comfort zones—whether that’s seeing an avant-garde play, checking out an edgy art exhibit, or even visiting one of the spaces we’ve featured—isn’t easy. But take heart—even the coolest culture vulture has felt this way, because intrinsically, art is about pushing our boundaries. You’re supposed to feel a little challenged—that’s the fun of it. What’s also important is to remember that art, in every form, is for everyone. “Just because you didn’t go to art school doesn’t make your opinion any less valid,” says Marcus Civin, an interdisciplinary artist and associate dean of graduate studies at the Maryland Institute College of Art. So, we’ve outlined some tips to help you make that leap into the unknown.

Bring someone along

A friend or partner will make you more comfortable, and you can discuss what you’re experiencing. Ryan Patterson, public arts administrator for the Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts, often brings his two children to cultural events. “They ask questions that I would be afraid to ask,” he says. “I learn more about the work, and that always makes it a better experience.”

Talk to the artist

Don’t feel like you’re imposing on their time —they’d likely love to talk to you. “Very few people come up and say, ‘This is awesome,’” Civin says. “Even the person sitting at the front desk is sometimes the gallery owner. Just start chatting about what you see.” That interaction will help you understand what you’re seeing—and your reaction to it.

Trust yourself

Don’t worry if you don’t like a piece of art, or have a strong reaction to a band’s music. That will only help you define what your taste is. And if you feel like it, share your opinion. As Civin says, “I would rather have someone come up and say, ‘This is crap,’ than nothing at all. It’s just as important to have people with jobs in accounting or science come to galleries and museums.”

Terrault

218 W. Saratoga St.

It’s a sweat-soaked Saturday night and art patrons are lining up by the elevator at the Maryland Art Place building near Lexington Market. Riding up to the

third floor, you hear the buzz before a ding announces your arrival, and when the doors open, you’re met with a bright, white-walled room, where an a.c.

window unit whirs. Along the walls is the work everyone has come to see, which, at the opening for this particular show, Wavy Dash, is an

exploration of line and color on small canvases, hung at different levels. One canvas is even tucked just at the top of the 10-foot ceiling.

▶ carlyn thomas hangs work before the opening of the show Wavy Dash.

There’s an excitement in the air as patrons—who hold Natty Bohs and favor high-rise denim shorts, tattoos, and half-shaved haircuts—take stock of the work. But there’s a close-knit community feel as well, as attendees greet one another with hugs and pause to discuss the pieces. And buzzing around the room, greeting everyone with big smiles that seem to counter any hipster malaise, are co-directors Brooks Kossover and Carlyn Thomas. “Hi!” Thomas excitedly calls to one of the guests. “I haven’t seen you in, what, a week?!”

Kossover and Thomas are still in their 20s and just a few years removed from their art degrees, but they recognized a need for this kind of gathering place, regardless of what type of art was presented.

“What we were doing is a little different—we aren’t just a gallery. From the get-go, we were a multi-use art space,” Thomas says. “We were doing film screenings, dance performances, poetry readings, using it for public meetings and lectures. We feel like our mission is to push boundaries and make work we haven’t seen that provides a place for all ages, all constituencies, to feel welcome.”

The latest development has been Terrault’s location. Looking for a change of scenery, Terrault—named for the Greensboro, North Carolina, street where Kossover grew up—moved in July, after two years in Station North’s Copycat building, to a 620-square-foot space at Maryland Art Place (MAP) in the Bromo Arts District. Kossover and Thomas plan to feature community discussions, performances, and other events. “It feels good to be in Bromo,” Thomas says. “I really like that it’s an old neighborhood, but there’s this youthful vitality.”

Terrault has won acclaim from the arts community for its shows, which have featured the likes of Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize winner Wickerham & Lomax, artist and illustrator Beth Hoeckel, and an exhibition with jurors like Baltimore Museum of Art director emeritus Doreen Bolger and MAP’s director, Amy Cavanaugh-Royce.

On this opening night, both of these ladies are in attendance, and deep in discussion with each other. A dog, accompanying its owner, is also part of the patronage, but no one minds. As the night grows older, patrons cluster in groups outside, seeming unwilling for the evening to end.

Kossover wants to see more of this energy, as he hopes other galleries and arts organizations move to MAP. “That’s one of the things that’s so unique about Baltimore—no one is in competition,” he says. “It’s cool to see that spirit creating something so new and fresh. The scene is really on fire.”