After two decades of work, Baltimore artist

Amy Sherald finds success and a new chance at life.

The National Portrait Gallery is quiet on this Friday morning as a group of visitors makes its way to the third floor. In a dimly lit, sprawling gallery, past the Louis Comfort Tiffany windows and Thomas Hart Benton oils, they peruse the portraits—mostly photographs, though there are paintings and sculptures, too, all finalists in this year’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. Some of the works are large and take up an entire wall. Others are small and intimate. They depict all ages, body types, and ethnicities.

AMY SHERALD.

But one in particular stands out. She’s the woman in the navy polka dot dress. You can’t help but notice her, as she’s painted against a sky-blue background, staring out at you from the canvas with a determined look on her face. Her name is Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance) and when you get up close, she surprises you. Her face has African-American features, yet at this distance, you realize she’s painted in shades of gray—hues that exist outside the colors identified with race—and the blue background she stands against is textured with flecks of purple and red. But the most eye-catching elements, regardless of your distance, are the enormous red flower perched on her head and the absurdly large white teacup and saucer she holds in her white-gloved hands.

A voice asks everyone to gather, and the members of the media who make up today’s group carry cameras and recording equipment to an open space, where the National Portrait Gallery’s director, Kim Sajet, and the competition exhibit’s curator, Dorothy Moss, stand at a podium alongside some of the artists. After a few words of thanks, they announce the winner of the $25,000 prize and an opportunity to create a portrait of a living person for the museum’s permanent collection: “Amy Sherald of Baltimore, Maryland”—the painter of Miss Everything. They turn to look at the woman, who smiles slightly, without showing her teeth, as if she hasn’t quite realized that she now has the attention of the whole room. She is wearing a camel-colored cape and black pants that graze her ankles. But the most eye-catching parts of her outfit are the red, Saucony tennis shoes on her feet that match her bright red fingernails, and that mirror the bold, whimsical air of her painting’s subject.

The group strolls over to Miss Everything, as Sherald cautiously takes the microphone. “My work is inspired by fantasy with a little bit of reality,” she says. She remembers seeing the movie Big Fish, a Southern gothic fantasy, and “being jealous that I hadn’t thought of the idea first.” People laugh, and Sherald pauses, before taking a more serious tone. Her work has changed since she moved to Baltimore, she says, encompassing a more social context that explores identity and the roles of gender and race. But, she thinks she’s finally found what speaks to her. “I focused on creating a body of work that was an archetype, and I think it’s going to carry me for a while.”

Afterward, she is swept up in a wave of congratulators and interviewers. When she can take a break, Sherald steps into an alcove where a video screen plays footage of the judges discussing the competition. Miss Everything was one of the portraits “that really stood out,” Helen Molesworth says in the video. Chief curator of The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, Molesworth goes on to discuss the teacup—which, in a way, makes you forget about identifying Miss Everything as a real-life character. “It’s a very realistic painting in one way, yet the details are all quite surreal,” she says. “And the figure is very self-possessed and confident. A kind of, ‘I will stand here and wait until the world catches up.’” Another juror, photographer and professor Dawoud Bey, who happens to be in attendance today and has been peering over Sherald’s shoulder at the video screen, remarks, “I agree, a very striking painting.” At hearing those words, the until now stoic, self-possessed Sherald exclaims, “Ah!” and puts her head in her hands. The reality of the day’s event is sinking in.

Amy isn’t the only Sherald holding court at the Smithsonian museum today. Her mother, Geraldine Sherald, a tiny woman with a big presence, tells Moss, Sajet, and a gaggle of National Portrait Gallery staffers who encircle her as if she was the queen mother, “Amy called and said, ‘Mom, it’s the most important day of my life, you’ve got to be here.’” The ladies all smile ebulliently, squeeze Mrs. Sherald’s arm, and then insist on taking selfies with her.

A moment later, Moss notes to a bystander how remarkable it is that Sherald has won—especially since she is the first African-American, and the first

woman, to win the prize. And then, she leans in confidentially, her voice lowered, and says, “You know her story, right?”

Amy Sherald by the mural on a West Baltimore bridge that she helped several teens paint.

Four months after that momentous day, Sherald sits in her combined studio/living space at Highlandtown’s Creative Alliance, gazing at the walls. At one point this year, they were covered with the vibrant blues, yellows, and pinks of her portraits, but just recently those works were shipped off to an exhibit in Chicago and all of them sold. Now, the walls are the bright white of a just-rented apartment. Such is the paradoxical life of a successful artist.

Barefoot, in a black tank top and jean shorts, Sherald ponders that piece of her identity. Since the Outwin Boochever prize, and really for the last five years, her career has been on an upswing. She’s booked a show in New York for the spring of 2017, and has a waiting list for about 20 paintings following the sold-out show entitled A Wonderful Dream at the Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago. Her work is in collections at museums like the National Museum of Women in the Arts and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History & Culture. She’s been featured by The Huffington Post, the BBC, and The Washington Post, and this latest prize is an addition to a growing list of awards.

“People look at success like once you get it, it’s easy,” says Sherald, 43. “At least for me, I feel a little bit alone in it. It’s really overwhelming to go from desperation to striving for something, and then all of a sudden, it’s there. The presence of it is heavier than the absence.” She pauses and considers this for a moment. “It’s wonderful, but it’s definitely something to be reckoned with.”

That’s particularly the case because three years ago, Sherald’s life could easily have ended. Diagnosed with heart failure as an adult, she underwent a heart transplant and gained a new lease on life. But it was also the start of an at times difficult journey that is still continuing. Sherald feels the lingering effects of depression and anxiety, conditions that are known to follow heart transplants, and this has changed her personality slightly, she says.

“Success is wonderful, but it’s definitely something to be reckoned with.”

“It’s like doing a pull-up—once you get your chin over the bar, you’ll be happy. But post-transplant, I’m kind of constantly floating just below the bar,” Sherald says. “I’m always a little subdued.”

Today, she is feeling overwhelmed by her achievements. To meet the demand for her work, she’ll have to more than double her output—she usually paints one canvas a month. “I feel like I’m on survival mode,” she says. “It’s like, wait a minute, is this what I asked for? Is this my life? Is this what I wanted when I was like, ‘God, please let me be successful?’”

She is half joking. One-on-one, Sherald is funny, youthfully joyful and sassy, without losing thoughtfulness, and she seems to find humor and levity in every situation. But you can feel that there is sincerity in what she says. She folds her long legs under her on the couch with a tinge of vulnerability. “It’s scary,” she says.

Sherald’s success has baffled her, partly because she’s never thought of herself as the best artist. “There are people out there who I was in class with who are probably better painters and drawers than me. I just work really hard,” she says, before using an explanation she often turns to in her life—magic. “Maybe it’s good karma, or maybe there are some art gods out there, I don’t know. There’s really no rhyme or reason to why it happened. It just did.”

Though she’s always been naturally drawn to art—she remembers doing small drawings at the end of sentences in her notebooks during second grade in Columbus, Georgia—it wasn’t seen as a viable option in her well-educated family. “My father wanted me to be a dentist like him, or any doctor, really. There was this attitude of, ‘The civil rights movement was not about you being an artist,’” she says. Still, she remembers first recognizing art’s transformative power when, while on a school trip to the Columbus Museum, she saw a painting by realistic portrait artist Bo Bartlett that included the image of a black man.

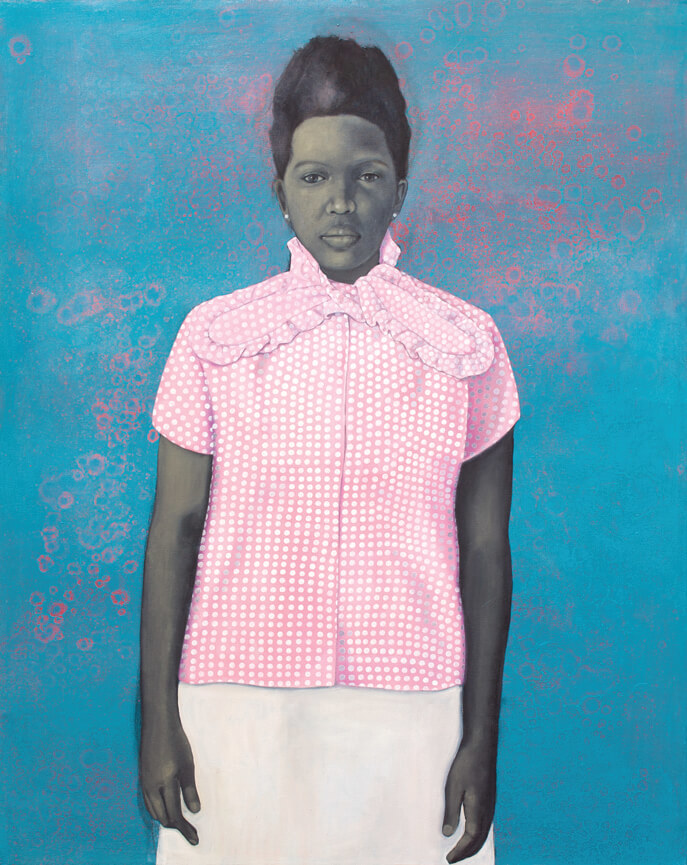

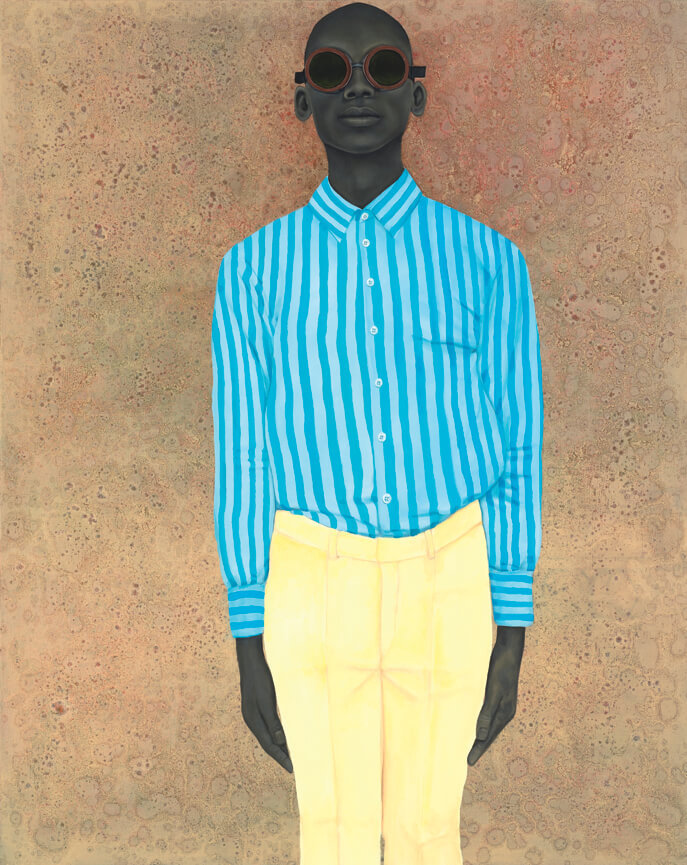

Sherald’s works, from left, Well Prepared and Maladjusted, The Boy With No Past,

and Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance).

“That was a seminal moment for me, to see this huge painting with a black figure in it,” she says. “At the time, I was in an all-white school, and I saw this man, and I was like, ‘Wow, he looks like me.’”

Already deep in self-discovery mode, Sherald’s world changed direction when she was a sophomore at Clark Atlanta University. After giving the premed track a try and worrying that she might lose her talent if she didn’t use it, she changed her major to art. She enrolled in a painting class at Spelman College—part of a consortium that includes Clark Atlanta—with the man who would become her mentor, Panama-born artist Arturo Lindsay, whose work focuses on the African influence on the cultures of the Americas. He opened her eyes to what it was like to be a living artist, and she knew she could learn from him, so after the class was over she asked if she could work for him for free.

“No other student had ever approached me like that. As an educator, those are the moments you wait for,” Lindsay says. That only added to his esteem for Sherald that he had developed from observing her in his class. “I’ve met a lot of students who could be very good painters or sculptors, but they aren’t necessarily good artists because they don’t have that hunger. They aren’t addicted to the stuff,” he says. “But Amy was from the beginning, and she only wanted to get better.”

Sherald worked for Lindsay for the next five years as she finished her undergraduate degree. She helped him prepare canvases, accompanied him on teaching assignments, and traveled with his art to exhibits—sometimes internationally—when his schedule did not permit. After she finished school, she started waiting tables, but she soon realized that graduate school would give her the added instruction and exposure she needed to advance her career.

At 28, Sherald began studies at the Maryland Institute College of Art’s LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting. She was in the last class to have Grace Hartigan as a teacher—the splatter technique she uses for her backgrounds is similar to the technique used by the renowned abstract expressionist artist. (Sherald says she and Hartigan squabbled at times, but a MICA program director later told her that Hartigan once said that Sherald reminded her of herself.)

But while Sherald’s art world was expanding, a visit to the doctor put everything into perspective.

Sherald hates telling this part of her story. “It sounds corny,” she says. But since she was a little girl, she’d had a dream in which she ran a marathon and died. At age 30, while training for a triathlon, Sherald decided to see a doctor, just to ease her mind. Instead, she discovered she had heart failure. “I would have been one of those athletes whose heart just stops and no one knows why,” she says. “I didn’t have any symptoms, but my heart functioning was down to 18 percent.”

In every other way, she was perfectly healthy, and doctors decided to keep a close watch. So, though the threat of heart failure and possibly death loomed, Sherald continued living life, finishing graduate school, traveling to Norway to study with artist Odd Nerdrum, and moving back to Georgia to take care of her mom and two aunts after her father’s death. But she felt the urge to return to Baltimore, to continue the exploration she’d started here.

By then, in her mid-30s and still waiting tables, Sherald began to seek out different ways of seeing herself and other African Americans. That led her to photographs that the writer W.E.B. Du Bois had compiled to be displayed at the Paris Exposition in 1900, depicting African-American men, women, and children in a way that countered some of the mocking and discriminatory representations of the day. “They have this stillness and dignity,” Sherald says of the photos. “I wanted to emulate the quiet presence I saw in those pictures, which were some of the first images where blacks were able to present themselves the way they wanted to be seen. Painting images that look like that was really important, not just for ourselves, but for the rest of the world to see us that way, too.”

Her dream is for people “to look at a black child and see themselves. . . . That’s the magic I want all of my paintings to have.”

Sherald’s work changed from self-reflective and romanticized into a style in which she emulated old masters and tried to marry that with her experiences as a black woman. “I’d go through all these art books and look at technique, but not necessarily see my story represented,” she says. She also started to analyze her presence in the different atmospheres of Baltimore and Georgia and thought of her own experiences, being from a proud, well-established family—her great-grandfather started the oldest, black-owned business in her hometown. On her canvases, she experimented with capturing that awkwardness of not knowing how to fit in, of having different identities, of being stereotyped, and then blended in elements of fantasy that set her subjects free from stereotypes and constraints of the past.

“I’ve always been able to deal with my life through fantasy,” says Sherald, who counts Alice in Wonderland as inspiration. Her dream, she says, is for people “to look at a black child and see themselves. I want my paintings to take you to a different space in reality, and allow you to recognize yourself,” she says. “That’s the magic that I want all of my paintings to have.”

Even the way Sherald chooses her portrait subjects has a quality of make-believe. “It’s instantaneous,” she says, adding that sometimes they are friends, though many times they are strangers. “When I see somebody, it’s that person. There’s something about them. Then I have to work up the courage to chase them down.”

Her first painting that she considers truly successful was her 2008 work, Well Prepared and Maladjusted. In it, a female subject wears an ill-fitting pink checked blouse, buttoned up to her neck, with a too-large bow. Her stiff posture seems to scream how uncomfortable she feels, though her face holds no expression. Sherald’s intention was felt around the country, as the work was selected as a jurors’ pick for the art journal New American Paintings. It has since sold, and it is the one painting Sherald says she will try to buy back if she can.

“That was the transition painting for her,” says Dana Reifler Amato, an artist who became close friends with Sherald while they attended the Hoffberger School of Painting. “It was clear that everything else up until that point had been preparation for that. It was amazing. For years, I had told her, ‘Amy, you’ve got to keep painting. Don’t over think it, it’s all going to work out, because what you’re doing is important.’ And she kept painting, and hallelujah, right?”

But it wouldn’t be that easy. First, Sherald’s 35-year-old brother, Michael—the one who was mistakenly called her twin because they were so close as children—was diagnosed with Stage 4, nonsmoking lung cancer. Then, while visiting him in the hospital in Georgia, Sherald felt out of breath and tired simply walking from the car to his room. “Okay, something’s wrong,” she thought.

Back in Baltimore, doctors discovered that her heart was functioning at 5 percent, and they immediately scheduled her for a transplant consultation. The day before the appointment, in October 2012, Sherald was at the Rite Aid close to her then studio near Lexington Market, when she felt her heart flutter. “Most of the time when that happened, I would prepare myself to fall just in case, and it would go away, it would fix itself,” she says. But that time it didn’t. Sherald awoke on the floor, with blood around her head. Amid the chaos of customers, the manager told her they’d called an ambulance. En route to The Johns Hopkins Hospital, reality began to sink in. “I felt like I could die then,” Sherald, then 39, recalls. “I actually felt that for the first time, and it did scare me. I thought, ‘I can’t be afraid to die,’ so I just made peace with it at that moment. I said, ‘I’m not going to be afraid, it’s all going to be okay.’”

At Hopkins, doctors determined that she needed a transplant. They gave her medicine to help her heart beat a little faster and fitted her with a port, which nurses checked on their rounds to see how her heart was functioning. While she played the waiting game for a match, Sherald, as usual, made the most of it, and controlled what she could in an uncontrollable situation. She organized the desk that swiveled on her bed daily, held wine parties in her hospital gown—“I could have a little bit,” she says—and rooted for the patients in surrounding rooms. Friends were constant visitors—like Amato, who served as a stand-in family member while Sherald’s mother and sister were keeping watch over her brother—and many stayed on the pullout couch.

When news of Michael’s death reached her in December, Sherald felt surprisingly at peace. “I was able to talk about my brother’s death with him while it was happening,” she says. “You’re mourning while they’re still here, in a way, and when it’s over, it’s a sense of relief. He gave me permission to move on while he was alive, and then I had a new guardian angel.”

Eleven days later, on Dec. 18, doctors told Sherald they had a match, and everything moved quickly. Nurses prepared her body for surgery—including taking out her belly ring, which she never got back—and in she went. Six hours later, she opened her eyes and woke up to Amato holding her hand. Not realizing that she was connected to a respirator, which was breathing for her, Sherald looked up at her friend and mouthed, “I can’t breathe.” “I told her, ‘Amy, you’re breathing, everything’s fine, just relax.’ And she lifted up her middle finger and rolled her eyes,” Amato says, laughing at the memory. “Even from the first minutes awake, she was all Amy.”

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing from there. The anti-rejection meds made her sick, which extended her hospital stay until she was finally released on New Year’s Eve, 2013. Her physical recovery moved quickly, but psychologically and emotionally, Sherald wasn’t feeling like herself. She was constantly crying and felt paranoid and anxious, sometimes so much that her hands shook and her teeth would start to chatter. Plus, she had no desire to paint. “I told my friends, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore.’ It felt stupid and selfish,” Sherald says. “I thought, ‘Maybe I should start a new life.’”

Sherald shuffles around her studio, grabbing chocolate for herself and giving a treat to August Wilson, her Pekingese-Jack Russell terrier mix with an adorable under bite who is named for the famous playwright. Upon hearing Sherald’s story, certain items in her living space make more sense—the pill bottles and inhaler that sit on a shelf, for example.

She got August Wilson after the transplant, and the companionship eased her anxiety. She also went to a psychiatrist, who helped her understand exactly what she was feeling and why, and who also prescribed a low dose of the antidepressant Zoloft. “That’s the part of the transplant where they can’t really tell you what life is going to be like afterwards—the psychological and emotional struggles of having to take drugs for the rest of your life,” Sherald says. “It’s changed my personality in certain ways. I don’t feel those little enlightened bubbles anymore. I don’t mean to sound unappreciative, because the alternative is death.”

“i felt like i could die then. . . . It did scare me. i thought, ‘i can’t be afraid to die,’ so i made peace with it at that moment.”

Therapy also helped her start to paint again. She’s continued with the same subject matter, but also exposed herself to new experiences that, combined with the events following the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Freddie Gray in Baltimore, grew the social justice component of her work. (She also painted Miss Everything during this time.) She taught art to inmates in the city jail for a year, and in the summer of 2015, helped teenagers paint a mural on a West Baltimore bridge through a Youth Works and Jubilee Arts Baltimore project. “There’s a lot of things I want to do, and a lot of ways I want to engage, not just sit back and make money,” Sherald says. “I got a second chance in life. I have Kristen Lin Smith beating inside of me right now.”

Smith, whose picture is on her coffee table, died of a heroin overdose, and her heart was transplanted inside of Sherald. Her family, whose picture is also on the table, remains in close contact with Sherald, and has cheered her on through all of her accomplishments. “I really wish my brother could have been a donor, but he couldn’t because of the chemo,” Sherald says. “I can only imagine how excited I would be if someone had his heart. So I’m really happy that her family wanted to reach out to me. It’s been a fairy tale of a story.”

Sherald is still considering the impact her second chance has had on her work, but Amato detects a change. “That sense of urgency in making the most of your life while you’re alive, the fragility of it, gave Amy permission to give painting her all,” she says. “She talks about setting her subjects free, and in a way, the transplant set her free to be a painter. She owed it to herself to give it everything, even with all of the doubt and self-criticism that we all face.”

Arturo Lindsay believes that Sherald appreciates the success that has come her way, and that she’s more optimistic than ever that she’s changing the way the world views her subjects. “I remember her talking with me after a fellow student had gotten a bump in his career, and I told her, ‘Sweetie, in a short time, you’re going to be up there also. Just continue to do what the heck it is that you’re doing.’ And she said, ‘You think so, Papi?’ And sure enough, you see where she is now.”

Sitting on the couch, Sherald turns her focus back to logistics. She types up notes for an artist’s talk and ponders how she’s going to get a dozen more canvasses prepared, when Cameron Shojaei, another resident artist at the Creative Alliance, bursts through the door and starts a lively discussion about Sherald’s show in Chicago. “You’re the perfect example of This American Life right here, if they do a show about discovery or something,” he says. “You’re getting discovered right on time, though I bet it seems late as hell, doesn’t it? Call Ira Glass, he’s from Baltimore.”

Sherald looks down bashfully. “Oh no,” she says, with a slight smile.

Shojaei continues. “You’ve got to make like 30 or 40 paintings this year, right? You’re probably at 100 paintings now, right?”

Sherald shakes her head. “I’ve only made maybe 35.”

“No way!” Shojaei exclaims. “Well, Vermeer only made about 40 works. So you’ll top Vermeer in no time.”

She’s laughing now. “Whenever I want to be entertained, I talk to you,” she tells Shojaei.

He grins, and says to her, “This is a real modern artist right here.”

Sherald is beaming. She knows that no matter how hard it’s been, and might continue to be, what she’s feeling now is magical.