A Tale of Two Cities

For half a century, West Baltimore was a vital center of black culture, mixed-income neighborhoods, and groundbreaking civil rights activism. After Freddie Gray, can it be again?

Private Thomas Broadus, a 26-year-old draftee at the outbreak of World War II, did what any African-American serviceman stationed at Fort Meade with a few dollars in their pocket would do: He headed to West Baltimore. Louis Armstrong was in town for the weekend, playing at a venue along Pennsylvania Avenue, a hub of black culture and entertainment rivaled only by Harlem and Washington, D.C.’s U Street district. It should have been one of the most memorable nights of the young soldier’s life.

Instead, it was his last.

Late in the evening of January 31, 1942, on the bustling corridor simply known as “The Avenue,” after several cabs refused to pick up Broadus and his four companions, they eventually decided to grab a lift from an unlicensed hack. A nearby white police officer intervened, however, demanding they wait for service from one of the city’s white-owned taxi companies. Broadus and the officer, a man named Edward Bender, ended up arguing, reportedly after Broadus said he “wanted a colored cab and had a right to spend his money with whomever he chose.”

"while progress has been made, deeply rooted, systemic drivers of racial discrimination, economic injustice, and poverty remain in place," Rev. Brown says.

At that point, Bender grabbed Broadus, striking him repeatedly with his billy club as the two men stumbled into a scuffle on the sidewalk, according to scores of witnesses. The serviceman—a Pittsburgh native and married father of three small children—regained his balance and tried to run, but Bender rose, aimed, and shot him in the back. As Broadus fell and then attempted to crawl under a parked car, the officer shot him a second time and “dared him to move.” He also began kicking the private, who remained pinned beneath the automobile, and was later pronounced dead minutes after arriving at nearby Provident Hospital.

Although criminal charges were initially filed against Bender—who had killed another black citizen two years earlier—they were dropped without explanation.

The shooting of a black American soldier in the middle of busy Pennsylvania Avenue became a call to action in a West Baltimore civil rights community already steeped in a struggle over segregation and social justice causes. Far from an isolated incident, Broadus’s death marked the 10th killing of a black citizen by white city police officers over the preceding three years, the Baltimore Afro-American reported at the time. The newspaper described West Baltimore as “a tinderbox.”

In the fall of 2014, following the shooting death of unarmed Michael Brown by a white officer in Ferguson, MO, Rev. Heber Brown III, a politically active local pastor, recounted the forgotten Broadus story during a town hall with Rep. Elijah Cummings and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. Brown told of how 2,000 people—led by Afro publisher Carl Murphy and Baltimore NAACP chapter founder Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson—demonstrated in Annapolis following the Broadus shooting. Some protesters said they had walked the entire 25 miles from Baltimore.

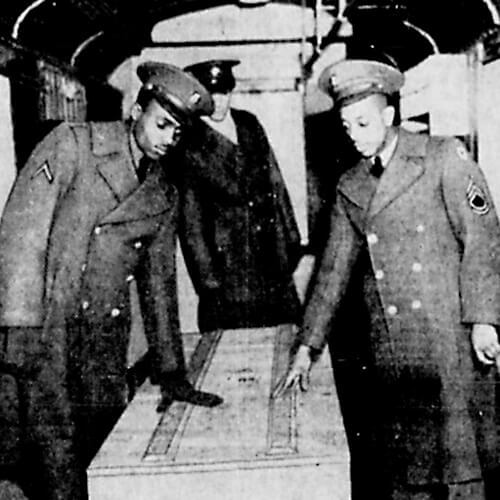

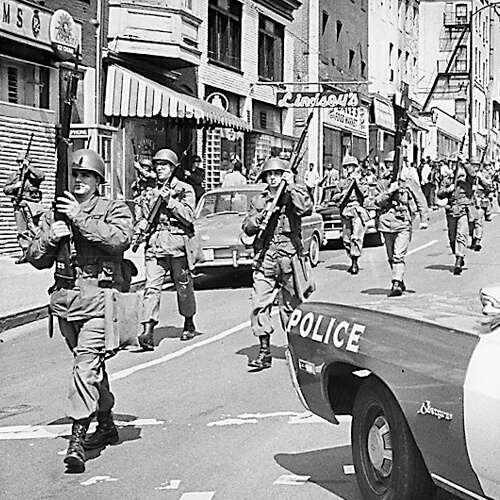

Casket of Pvt. Thomas Broadus, who was killed by a white police officer on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1942; The National Guard in Baltimore during the ’68 riot.

–Reprinted with permission from The Baltimore Sun Media Group: All Rights Reserved; reprinted with permission from the Baltimore Afro-American Newspaper

A few months after that town hall, 25-year-old Freddie Gray would die from a severe spinal cord injury suffered while in police custody only blocks from where Broadus was killed. And this time, as it had in 1968 after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the lid, briefly, blew off West Baltimore. But then, after the riot of April 27, the unrest quickly coalesced into a series of peaceful demonstrations and demands for change—not just to end police brutality, but also for broader criminal, economic, educational, and housing justice—that have not abated since Gray’s death.

The same thing had happened after Broadus was killed. Police reform—including a request to put the first black police officers on patrol in the city—was the initial demand, but that uprising also expanded into calls for wider action around education, jobs, housing, and public health issues.

That’s the broader link from 1942 to Freddie Gray and what’s happening right now in Baltimore, Brown says today, adding that while progress has been made, deeply rooted, systemic drivers of racial discrimination, economic injustice, and poverty remain in place—including plenty erected after Broadus’s death.

“Seventy-two years ago,” the pastor had thundered during that town hall with Rawlings-Blake, Cummings, and other religious, law enforcement, and community leaders, his voice quaking with emotion. “And I’ll be damned if my grandchildren are going to fight a fight that we have the power right now to end in our community.”

Vacant Homes in Freddie Gray's Sandtown neighborhood.

In the aftermath of Freddie Gray’s death, the local and national spotlight turned to the West Baltimore area where he grew up and died. Plagued for decades by vacant buildings and lead-infested homes, hyper-segregated and low-income schools, a lack of accessible jobs and transportation, high unemployment and incarceration rates, open-air drug markets, violence, and recently, a sex-for-repairs public housing scandal that even The Wire for all its despair couldn’t have imagined, West Baltimore now appears at a crossroads. Police Commissioner Anthony Batts was forced out months ago as the homicide rate spiraled to record-breaking levels. Rawlings-Blake—much like former Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III after the ’68 riots—has declined to seek re-election along with more than a third of the City Council. And earlier this year, 35,000 people signed a petition calling for the ouster of housing chief Paul Graziano.

By any objective measure, the data from Sandtown-Winchester, Harlem Park, Madison Park, Upton, and Druid Heights is alarming. Infant mortality rates in parts of the 175-block neighborhood collectively known as “Old West Baltimore” are more than 3.5 times the national average. Life expectancy is more than 10 years below the statewide average, almost 20 years shorter than in Roland Park, which sits just a few miles away—ranking below famine-afflicted North Korea. Children in Sandtown-Winchester, where poverty rates surpass 30 percent, face the most dire economic prospects of the top 100 U.S. metro areas, and poor teens in the city deal with living conditions worse than their counterparts in Nigeria, according to recent studies.

But buried in West Baltimore, in between the majestic, if too often crumbling, three-story brick rowhouses—and sometimes literally inside those vacant homes—lies a history as compelling as any in the country.

Penn-North mural featuring Holiday and Ta-Nehisi Coates.

It’s here, for example, that Rev. Harvey Johnson, one of the few Americans born into slavery to leave written words chronicling his worldview, founded the Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty—the forerunner of the Niagara Movement and the NAACP. After being ejected from a B&O train for refusing to sit in a segregated compartment on his way to a 1906 Niagara meeting in Harpers Ferry, it was also Johnson who fought and overturned Maryland’s separate car rules for interstate passengers—some 60 years before the famous Freedom Riders. His home and the historic church he led, Union Baptist, both survive to this day on Druid Hill Avenue.

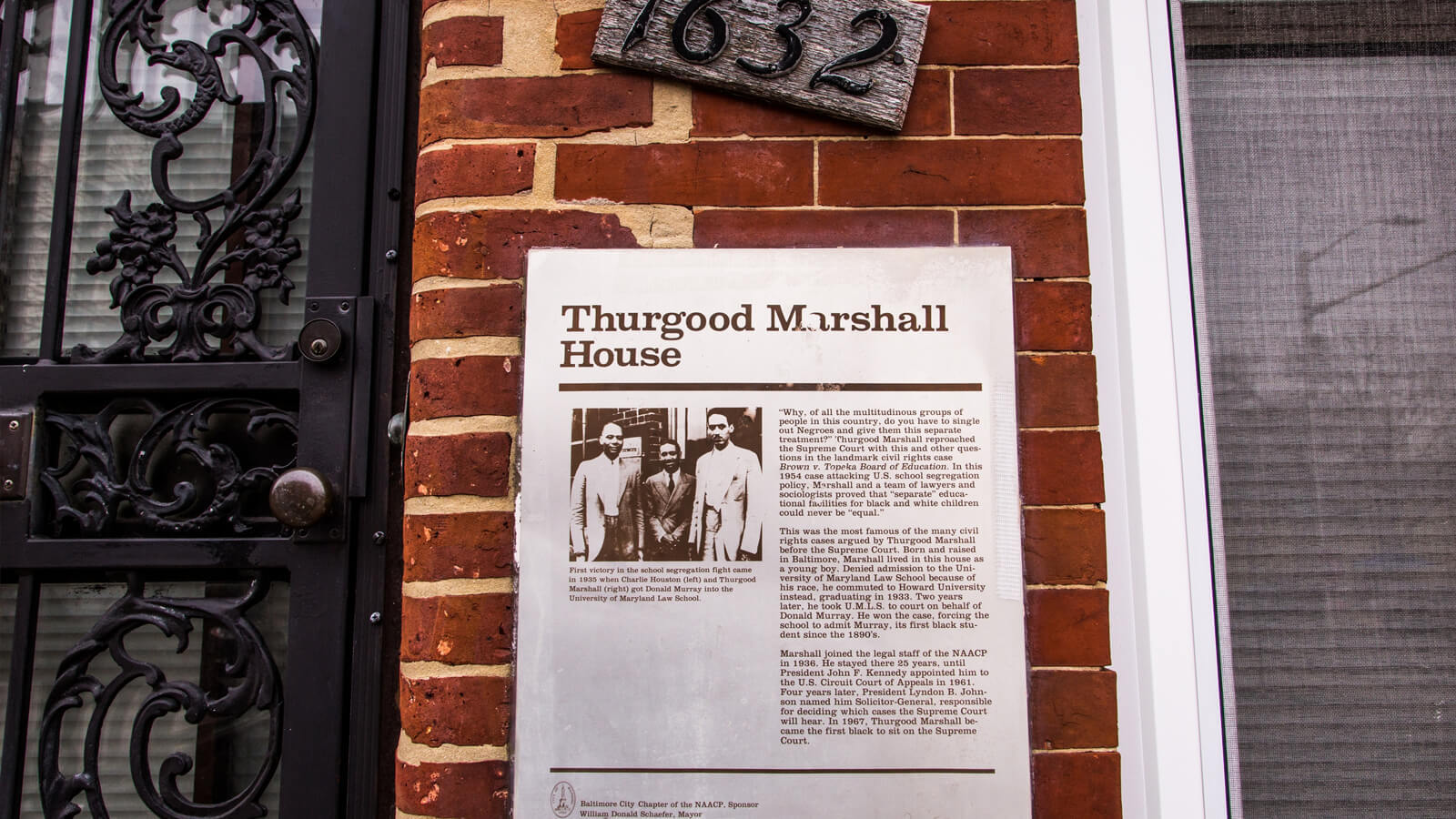

Similarly, it was Baltimore native Irene Morgan, a 27-year-old mother of two, refusing to give up her bus seat 11 years before Rosa Parks, who broke down a key constitutional interstate segregation law. In fact, her landmark case, reaching the Supreme Court, was won by Baltimore’s future justice Thurgood Marshall, who later argued and won the historic Brown v. Board of Education case. His boyhood home, which is intact, and elementary school, which is boarded, are here as well, though separated by several blocks of blight and struggling homes on Division Street.

And on it goes: Pioneering civil rights activist Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson met with Eleanor Roosevelt and Martin Luther King Jr. at the “Freedom House” on Druid Hill Avenue, which was unexpectedly and controversially razed last fall. Her daughter, Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the first African-American woman to practice law in the state, and son-in-law, Clarence M. Mitchell Jr. (nicknamed the “101st Senator” as the NAACP’s chief lobbyist during the civil rights legislation of the 1960s), kept their home and legal office here, too—although both sit in disrepair today. Parren Mitchell, the first African-American from a Southern state elected to Congress following Reconstruction, lived in a stately house that stands in solid shape—but amid other vacant homes—at the corner of Lafayette Square. And old Frederick Douglass High School, the city’s original “colored” high school, where the Maryland-born abolitionist gave the commencement address in 1894, and from which jazz legends Ethel Ennis and Cab Calloway graduated—as well as Marshall and all of the aforementioned Mitchells—still stands, too, now renovated into low-income apartments.

Baltimore’s former NAACP Chapter “Freedom House,” which was demolished unexpectedly and controversially last fall.

“This,” says Lou Fields, president of the African American Tourism Council of Maryland, “is one of the most historic black neighborhoods in the United States.”

In fact, the 111-year-old Arch Social Club, believed to be the oldest continuously operating African-American men’s club in the country, continues to host live music, dance classes, and galas at the corner of Pennsylvania and North avenues—directly across from the CVS store that the country watched burn on television last April.

And still, none of this scratches the surface of the black renaissance that flourished starting in the 1920s. Ragtime legend Eubie Blake got started here and Billie Holiday lived on this side of town for a period. They, along with Calloway, Armstrong, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and later, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, The Supremes, and Etta James—whose classic “At Last” has been covered by Adele and Beyoncé—lit up the bills at venues like the Royal Theatre, Sphinx Club, and the Regent. Martha and the Vandellas, who give a shout out to Baltimore in their hit, “Dancing in the Streets,” were booked for an entire week in 1964—the same year James Brown released Pure Dynamite! Live at the Royal.

That was also the year civil rights activist and singer Nina Simone, who played here, recorded “Mississippi Goddam,” which acclaimed local jazz performer Navasha Daya re-adapted in the aftermath of Gray’s death: New York's got me so upset; Ferguson makes me lose my rest; and everybody knows about Baltimore, goddam.

But those clubs were not only black destinations. There were two entertainment centers in Baltimore—The Block and Pennsylvania Avenue—one built around women taking off their clothes, the other around music. Doctors from Johns Hopkins who played instruments were known to sit in at the Sportsmen’s Lounge, a jazz venue owned by Colts great Lenny Moore.

“Oh my, the whole of Pennsylvania Avenue was something in the evening,” says Rosa Pryor-Trusty, a West Baltimore native and former singer, promoter, club manager, and current Afro and Baltimore Times columnist. “Women stepping out in their dresses, with their fancy hats and gloves. The men putting on their best three-piece suits and polished, patent-leather shoes. Everybody walked The Avenue, going from one theater or comedy club or nightclub to the next.” Barred from staying in the segregated downtown hotels, entertainers generally stayed right in West Baltimore, if not at one of the three small black hotels, then sometimes at the Black Baltimore Musicians Union Hall and boarding house on Dolphin Street (which also still stands) or with a local family, shopping in the trendy clothing and record stores in the afternoons before shows.

“It does seems unreal when you see how things look today,” says Pryor-Trusty.

Iconic Royal Theatre; Louis Armstrong backstage at the Royal; Billie Holiday shopping on Pennsylvania Avenue.

–Photography by Henry Phillips

The Pennsylvania Avenue corridor and surrounding community was long something of an oasis in what was historically the largest segregated city south of the Mason-Dixon line. But as the Broadus killing illustrates, West Baltimore was never immune to the social ills plaguing the country—it represented the best, and worst, of the times. And then, in 1971, the iconic Royal, Baltimore’s version of Harlem’s Apollo Theater, was demolished in a failed “urban renewal” plan. The Royal marquee sculpture at a nearby park and the statue of Billie Holiday at Pennsylvania and Lafayette may be homages to the past, but they are also stark reminders of all that has been lost or destroyed.

“Pennsylvania Avenue was never a beautiful tree-lined kind of street, but there was always a visceral excitement, a buzz in that neighborhood,” says Camay Calloway Murphy, the 89-year-old daughter of the renowned bandleader. “You would’ve had to live it to fully appreciate it.” She grew up in New York, visiting her Baltimore cousins each summer, before later moving here and marrying John Murphy III, who succeeded his uncle Carl as publisher of The Afro. “There were movie theaters and play houses all over, too, seemingly on every block, a lot going on,” Calloway Murphy says. “But it was a place you felt safe as a kid.”

This is a point, too, that James Hamlin, who grew up in this community and opened The Avenue Bakery on Pennsylvania Avenue five years ago, emphasizes. Beyond civil rights icons and the heydays of jazz and Motown in the area, Old West Baltimore was a stable place to grow up. “The term today is ‘walkable neighborhood,’” he says as customers stream in for his homemade buns, muffins, and sweet potato pies on a Friday afternoon while Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” plays in the background. “We had that here. We had shops, dry cleaners, delis. As a teenager there were plenty of places to a get a job. I got my first job at 13 at Archie Ladon’s grocery store at Presstman Street and Druid Hill Avenue. It was enough money to buy my first pair of blue-tip Jack Purcells [Converse sneakers]. But there were also three newspapers to deliver, The Sun, News American, and Afro-American. And, if none of that worked out, you could always nail together a wooden shoebox and shine shoes on Pennsylvania Avenue.”

The 67-year-old Hamlin, who started unloading trucks with UPS in 1968 before working his way up to a series of management positions, returned to the neighborhood of his youth in an effort to bring back small businesses and stimulate commercial activity on the Pennsylvania Avenue corridor. The bakery, unharmed in April’s riot, has become not just a regular stop for customers, but also a mini-Baltimore civil rights museum—with murals, photos, bios, and historical timelines covering the walls, and a documentary about the city’s musical legacy looping on a television. “These were thriving residential neighborhoods,” he says. “There were lawyers, doctors, and teachers living on every block, right alongside people who were working in factories and doing whatever jobs it took to get by.”

Which begs the question: How did a neighborhood listed on the National Register of Historic Places end up in such condition?

Avenue Bakery owner James Hamlin.

The short answer to what happened to West Baltimore is sometimes proffered as “the riots,” meaning the four-night, April ’68 riots following King’s murder in Memphis. And it’s not a wrong answer—those riots sent white merchants, many Jewish with long ties to the community, and, eventually black residents with the wherewithal, fleeing for the counties. Six people were killed; more than 700 injured; 5,500 arrested; 1,050 businesses robbed, vandalized, or set afire; and an estimated $90 million in property damage in today’s dollars occurred (compared to the $9 million there was in last April’s riot). Of course, businesses and residents across the city left in huge numbers in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, too, with the tax base and jobs in close pursuit. But the riots didn’t create the ghettoization of West Baltimore—they were the capstone of decades of racially discriminatory laws and agendas.

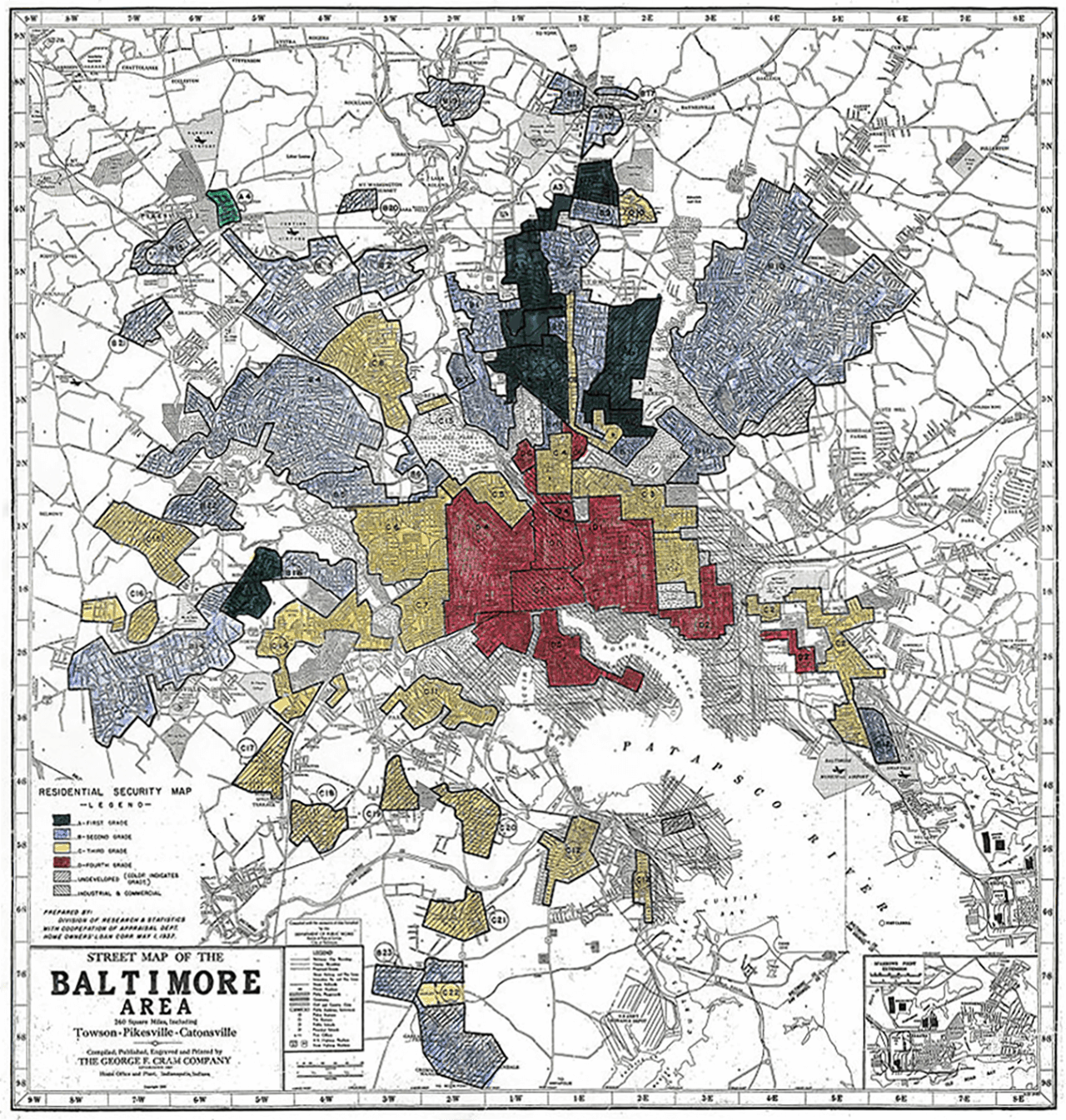

Like more than 100 cities—including New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Los Angeles, which experienced protests and riots in the mid-’60s prior to King’s death—Baltimore was coming apart because of myriad forces tied to first legal, and later de facto, segregation. Those practices included, but were not limited to, redlining by the Federal Housing Administration, whose officials literally drew red lines around minority neighborhoods on maps in order to discourage loans, and discriminatory distribution of G.I. Bill benefits, which included not just tuition and job-training money, but business and home loans as well. (In New York and northern New Jersey, fewer than 100 of the 67,000 mortgages insured by the G.I. Bill backed minority home purchases.)

Those practices were just part of the massive local, state, and federally supported suburban expansion—prohibiting blacks by written and unwritten policies—long before the riots following King’s murder. The ongoing segregation, furthered by the construction of public housing projects in already poor, minority neighborhoods, exaggerated its effects. It was a process that George Romney—the father of the former Republican presidential candidate and Richard Nixon’s first Housing and Urban Development (HUD) secretary—described as creating a “high-income, white noose” around the nation’s urban core. As governor of Michigan, Romney had seen it play out in Detroit.

At HUD, the Baltimore metro area was one of the first Romney targeted to promote integrated housing. At one point, he froze federal money tied to water, sewer, and park plans in Baltimore County unless it loosened its stance against low-income and minority housing. As far back as 1964, Baltimore Mayor Theodore McKeldin, a Republican, had attempted to work with then-Baltimore County Executive Spiro Agnew—considered a reformer—on a metropolitan-wide open occupancy plan. The County Council blocked those efforts, however.

In comparison to Dale Anderson, the Democrat who followed the eventual Nixon vice president into the Baltimore County executive office, Agnew was

a reformer. Out of political necessity, Agnew eventually opposed open housing laws, but Anderson was more blunt, decrying programs that would “bring hordes

of migrants.” In late 1972, he ordered real-estate brokers to report sales or rentals to African-Americans to the police, according to longtime former Sun reporter Antero Pietilla, author of Not In My Neighborhood. (Both Agnew and Anderson were later busted on tax evasion and corruption

charges during this particularly ignominious period in Maryland politics.)

This hand-colored 1937 Baltimore map, prepared by the government’s Home Owners Loan Corporation, redlined much of the center city (largely African American or Jewish). Since regular mortgages were nearly impossible to get, homes there could be sold only through speculators. –Antero Pietilla

Also, for Marylanders today who only know the state as a reliably blue bastion, it’s worth recalling that segregationist George Mahoney won the Democratic primary for governor in 1966 on the dog-whistle slogan, “Your home is your castle—protect it” and former Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, of “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” infamy, swept the state’s 1972 Democratic presidential primary.

But in truth, the wheels that set the demise of Pennsylvania Avenue and Old West Baltimore in motion date back further—to the first apartheid housing laws of Rev. Harvey Johnson’s era, derided then by The New York Times as “the most pronounced ‘Jim Crow’ measure on record.”

“This mess really begins in 1910 with the City Council’s first segregated housing law—Ordinance 610,” explains local historian Fields, to a small group he’s leading on a tour of Freddie Gray’s neighborhood and nearby civil rights landmarks. Fields’s driving tour, which he has been offering for several months, starts at New Shiloh Baptist Church, whose congregation hosted Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1953 and Gray’s funeral last April. From there it moves through the bleak area near Gray’s childhood home, where he and his sisters suffered lead paint poisoning, to the Western District police station—built atop a playground, it turns out—where the first protests erupted while Gray remained in a coma following his questionable arrest and ultimately fatal police wagon ride.

“Thurgood Marshall, the Jacksons, the Mitchells all walked these streets—so did Billie Holiday,” says Fields, pointing out several historic sites, including the former home of Baltimore’s first Colored YWCA.

One of the last stops is the Holiday sculpture, located three blocks from where Broadus was killed and between the fourth and fifth stops of Gray’s fatal transport. Among those joining Fields’s tour is artist James Reid, who created the striking bronze piece in 1985, capturing Holiday in full voice, which Reid describes as a “call to action.” At that time, however, he was not allowed to install the sculpture’s original base panels because one panel is designed around the jazz singer’s anti-lynching song, “Strange Fruit”— Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze; Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees. Ultimately, the panels were added in 2009.

The birthplace of first black Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall located at 1632 Division Street.

“A 24-year censorship fight,” says the soft-spoken, 73-year-old Reid, who pumped gas as a teenager in this neighborhood. “The entire work is metaphorical and the ‘Strange Fruit’ piece is more important than ever. To me, there’s an evolution from the lynching of young black men to mass incarceration of young black men and police brutality.

“You know, I had a very strict mother,” he continues. “And she taught me to be careful in how I move around a store and things like that. She told me to keep my hands close by my side and not to pick up anything until I was ready to buy it. Would you believe that I am still aware of that at my age now?”

That 1910 law that Fields highlighted, which Baltimore City Solicitor Edgar Allan Poe—a grandnephew named after the famous poet—had declared constitutional, did get overturned. But it served as the foundation of the segregated—if at least mixed-income—early black neighborhoods here. That legislation got its start after a Morgan State College alum and Yale-educated black lawyer named George McMechen bought a house on then all-white, well-heeled McCulloh Street just west of Bolton Hill. Until then, black residents lived in nearly every ward, but the uproar over McMechen’s residency led to block-by-block partitioning while actually making the sale of a white-owned home on a “white” block to a black purchaser, and vice versa, illegal.

Exclusionary covenants, blockbusting, predatory lending, and more recently, of course, targeted subprime loans, followed. Inevitably, the “high-income, white noose” tightened over time as top-down policies promoted a continual shift of resources to the suburbs, while de-industrialization, lead paint crises, the drug war, mass incarceration—supported by everyone from presidents Nixon, Reagan, Clinton and both Bushes, to former Mayor Martin O’Malley—piled on urban areas. And, as in other cites, there was also the construction of an urban freeway through West Baltimore—the I-70 stub, which was never completed and became an unnecessary addition of Route 40. These went through poor, minority neighborhoods—including the disastrous “Highway to Nowhere,” which destabilized a vast swath of neighborhoods in the late ’60s and early ’70s, displacing more than 3,000 residents and dozens of businesses.

The open wound of segregation prevented several generations from building the wealth that typically flows from homeownership, says Richard Rothstein of the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank. He notes that, while black family incomes are about 60 percent of white family incomes, black household wealth is only 5 percent of white household wealth. “In Baltimore and elsewhere,” he says, “the distressed condition of African-American working- and lower-middle-class families is almost entirely attributable to federal policy that prohibited black families from accumulating housing equity during the suburban boom that moved white families into single-family homes from the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s—and thus from bequeathing that wealth to their children and grandchildren, as white suburbanites have done.

Somewhat infamously, future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson and his family struggled for months to buy a home in segregated Baltimore in 1966 because of their race. At one point, his wife came close to leaving the city and returning to California with the couple's two children.

“Look at those Levittown, NY, homes built after World War II, which excluded blacks,” Rothstein says. “They now go for upward of $400,000 and $500,000. Things like helping a child pay for a college education or put a down payment on a house are out of reach for poor, or working-class, minority families.”

Against this history, the data revealing dramatically diminished opportunities for people in the city’s poor neighborhoods should not come as a surprise.

“Baltimore has always been a tale of two cities,” says Marvin “Doc” Cheatham, former head of the NAACP’s Baltimore Chapter and current president of the Matthew A. Henson Neighborhood Association, which represents the same community where Freddie Gray attended elementary school. “There’s always been the well-to-do Baltimore and other Baltimore. But there’s also the tale of West Baltimore—how it used to be—set against how it is now. Poverty and struggle have always been a part of the story.

“The question is, do we have the political will to move forward?”

Cheatham’s query is a good one.

Like many other African-American Baltimore activists, he has been frustrated by the city’s now majority black political leadership’s inability to address the systemic issues facing West Baltimore.

Harry Sythe Cummings, Baltimore’s first black city councilman, was elected in 1890 and served several terms, but during the key mid-century period from 1930 to 1955, there was no black representation on the City Council. From 1955 to 1967, just two of its members were black, and it wasn’t until 1987—when the damage seemed irreversible—that Kurt Schmoke, the first elected black mayor, took office. Now, of course, the City Council maintains a consistent black majority, but along with Rawlings-Blake, it has come under fire for approving tax breaks for Inner Harbor projects that hurt public school funding. Over the longer haul, activists have condemned officials for selling out to developers while tripling the police department’s budget during the past 25 years and shuttering recreation centers.

“So many things have happened, but we can’t point the finger at anybody but ourselves anymore,” Cheatham says. “It’s poor political leadership—the Baltimore Development Corporation [a nonprofit whose mission is to boost the economy] isn’t doing anything here. For starters, we could use funding and tax credits to rebuild vacant houses, putting unemployed residents to work learning rehab skills and earning credit toward homeownership.”

That said, larger forces still can throw up enormous obstacles to potential growth in West Baltimore: The cancellation by Gov. Larry Hogan of the decade-in-the-works, nearly $3 billion Red Line project was a crushing blow, and the decision has been challenged by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which alleges the action violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964. According to the complaint, a transportation economist using the state’s own models, “found that whites will receive 228 percent of the net benefit from [Hogan’s] decision, while African-Americans will receive -124 percent.”

“The term today is ‘walkable neighborhood,’” says bakery owner james hamlin, while sam cooke’s “A change is gonna come” plays in the background. “We had that here.”

In large part, the project was viewed as a remedy for decades of disparity in transportation spending, as well as an attempt to address specific needs in areas like Sandtown-Winchester and Harlem Park, where residents have the city’s longest average commute times. The U.S. Department of Transportation is currently investigating the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund’s complaint.

Yet resources remain in West Baltimore—not the least of which is its history, which residents, along with the nonprofit Baltimore Heritage, are working to preserve. There’s also a committed community of citizens that show up in inspiring numbers at public safety meetings, candidate forums, and town halls. A recent Saturday city budget workshop packed the Enoch Pratt Free Library conference room at Pennsylvania and North avenues for three hours. And there’s also the historic churches—Union Baptist, Douglass Memorial, and Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist, among others—that remain anchor institutions.

Besides Hamlin’s bakery, other enterprises are popping up. Most notably, an “Innovation Village” collaboration between the Maryland Institute College of Art, Coppin State, the city, business and community groups, has launched in hopes of attracting tech start-ups to the Penn-North corridor. Two firms already have committed. Nalley Fresh, a local restaurant chain, is looking at opening on The Avenue, and Hamlin, who also hosts live music in his store’s courtyard from May through October, says long-held plans to rebuild a new Royal Theatre are more promising than ever.

And early this year, Hogan announced $75 million in state funding over four years, along with an annual $10 million pledged by Rawlings-Blake, to demolish blighted buildings. Some feel it’s a start. Monica Cooper, who grew up in Sandtown and co-founded the Maryland Justice Project, attended that January Hogan-Rawlings-Blake photo-op in her old neighborhood. She isn’t convinced that merely knocking down vacant rowhouses will accomplish a great deal. Cooper says more is needed, including programs to fix houses and keep residents in the neighborhood.

“There’s different ways people look at Freddie Gray, his death, and everything that happened afterward,” she says. “Some people look at his background and just see a hustler, someone dealing drugs on the corner. Other people see him as a martyr. Other people knew him as a friend. What I know is that what happened to him should never have happened. I also know that sometimes it takes a tragedy for a change to take place.”

New leaders are emerging as well, and they express optimism, if cautiously, for West Baltimore.

Ericka Alston, a public relations specialist, was inspired to create Kids Safe Zone, an afternoon, evening, and weekend youth space in Sandtown-Winchester in the immediate aftermath of Gray’s death. (Alicia Keys made a memorable stop after learning about the work being done there.) Like Devin Allen, the photographer who shot the Time cover image of last April’s riot, and Dominic Nell, another local photographer, Alston has become an activist on multiple levels, supporting political empowerment while also tackling the immediate needs in the neighborhood.

Ericka Alston and photographer Dominic Nell working with youth at the Kids Safe Zone.

“I have hope. I do,” says Alston. “But even if I didn’t, I’d still be doing this.”

Allen, 27, and Nell, 39, grew up in the neighborhood where the unrest unfolded and have been mentoring children in the art of photography, with an exhibition planned for this summer. With the highest tally of Baltimore’s record-worst 344 homicides last year coming from the Western District, neither is naïve about overnight turnarounds here. But both feel a deep responsibility—and love—for the community they’re from.

“My family goes back generations here. My house is right behind where the curfew confrontations took place,” says Nell, a quiet, thoughtful presence among all the kids rushing around. Farther down Pennsylvania Avenue, there are other thriving community spaces, he notes. The Upton Boxing Center, for example, offers top-notch coaching. Gervonta Davis, an undefeated, professional featherweight supported by former champ Floyd Mayweather, trains out of the gym.

Nell also mentions the enduring Shake & Bake Family Fun Center—a roller skating and bowling arcade created by former Colt Glenn “Shake and Bake” Doughty in the early ’80s—and the more recent Strawberry Fields Urban Farm effort, plus the success of Martha’s Place, a former vacant building turned drug addiction recovery and transitional long-term housing facility for women. And, across the street from Martha’s Place, there’s Jubilee Arts, which offers dance, art, and business classes for students. “St. Peter Clavel Catholic Church is there, too, one of the oldest in the city,” Nell muses.

The Upton Boxing Center; photographers Devin Allen and Dominic Nell working with youth at the Kids Safe Zone, launched by Ericka Alston.

“That’s the thing, though,” he continues. “All that is surrounded by vacant lots, boarded-up homes, and that junkyard—the scrap metal and salvage place where there’s always a line of people hauling stuff in. Down the street from Jubilee Arts, where those little girls do ballet in their pink leotards, I saw a metal coffin once being scrapped for cash.”

Nell pauses.

“But that’s the way Baltimore has always been,” he says. “It’s what a good friend of mine who is no longer around used to say: ‘In Baltimore, beauty and chaos live side by side.’”