Arts & Culture

Full Force

A local organization combines art and activism to support survivors of assault.

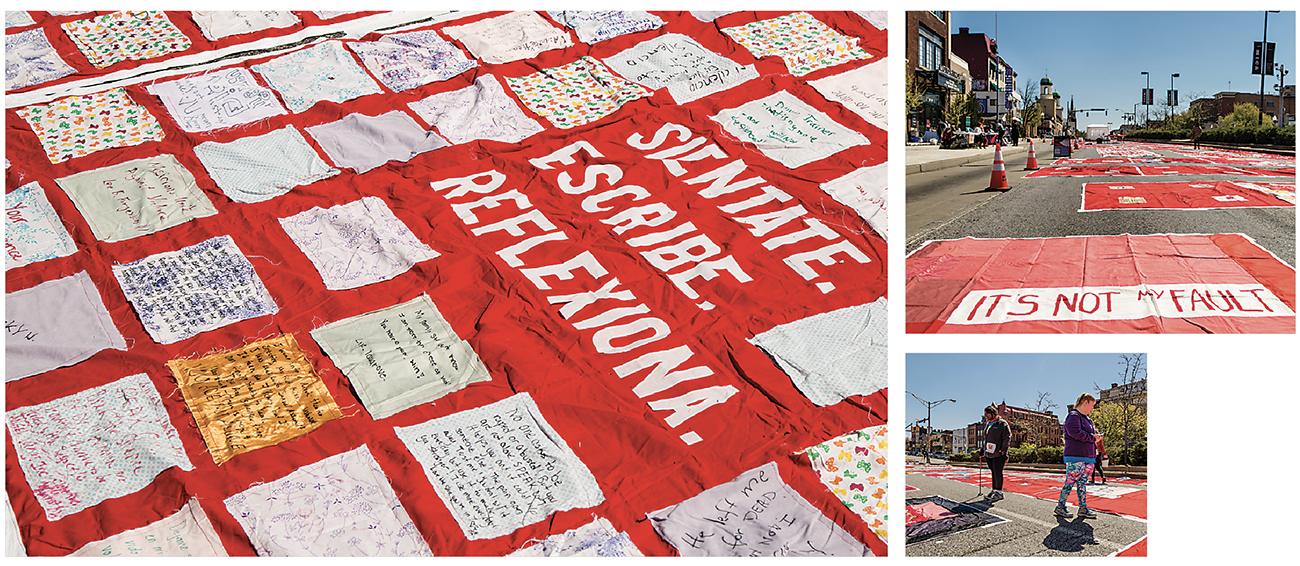

One afternoon in March, in a sun-drenched studio at Station North’s Motor House, a quilt begins to take shape from pieces of eye-catching red fabric. Women scurry to various stations to cut and measure the bright swaths of cloth, then head to whirring sewing machines where spools of unraveling thread transform them into squares. The scene might seem routine, but it doesn’t take long to find the poignancy in the work of this modern-day sewing circle. The red squares contain messages, written any manner of ways—looping script, bold block letters—that describe the experiences and emotions of survivors of sexual and domestic violence.

Some of the messages are empowering—“You are precious,” reads one in black permanent marker. Others more directly reveal what their authors endured. As volunteer Twig George pulls a piece of fabric decorated with butterflies from a cardboard box, she gasps as she reads, “I was so small, he was so big.”

“Sometimes, I forget how significant these squares are, how meaningful,” George, an author of children’s books and a school librarian, says later. “The first time I worked on the quilt, I got really upset. But now, when I work on it, I use it as my way to honor what these survivors went through.”

When George finishes this square, it’s added to others that encompass the creation known as The Monument Quilt. Inside gray plastic tubs lining the studio walls, this work of art waits to unleash its message to a national audience in the fall of 2017. Its creators hope that, like the AIDS Memorial Quilt of the 1980s, The Monument Quilt will force the country to think about an issue that is often hidden from the public eye, and place it on the largest of stages—the grass along the National Mall.

“Re-connecting to and feeling secure in community is a necessary part of healing from trauma,” says Rebecca Nagle, co-director and co-founder of FORCE: Upsetting Rape Culture, the group behind The Monument Quilt. “That’s why we have public monuments and memorials to honor victims of natural disasters and of war. Our culture recognizes that those survivors need to be re-connected, but we don’t have that for survivors of sexual and domestic violence. They are isolated.”

“It was finding a way that art can have an impact.”

From its beginnings, Nagle and fellow FORCE co-founder and co-director Hannah Brancato wanted to use the quilt to make this bold gesture. It deftly fits in with FORCE’s other actions, which have garnered national attention and local commendation by blending art, activism, and community. Similarly, the quilt has multiple missions.

“It’s a combination of wanting it to be very welcoming for survivors and something that interrupts people’s thinking about where we should talk about sexual violence,” Brancato says. And, “it’s a call to action.”

If you’d asked Brancato and Nagle back in 2013 how long it would take to create The Monument Quilt, they would have told you a year.

They laugh about that now. Sitting in their studio, amid the ever-present sewing machine buzz, they talk about how their first Kickstarter campaign for the project told potential donors that the quilt was heading to the National Mall in 2014.

“I guess we could work like [commissioned] artists and get a bunch of money and red fabric and just do it,” Brancato says. “But that’s not really what this is about—it’s about community building and community organizing.”

Although she and Nagle met in the mid-2000s while both were fiber majors at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), they didn’t work together until 2010. By then, Nagle was producing a satirical play she’d also written that drew on her experiences as a survivor of childhood incest. Brancato was a resident artist at the intimate-partner violence center House of Ruth, drawn to work there after returning from a trip to Turkey and seeing gender roles in America in a new light. While working at House of Ruth, she realized that she, too, was a survivor of abuse.

Together, she and Nagle produced an art show at Current Gallery called FORCE: On the Culture of Rape. When they decided to create an arts collective, they used the art show title—retaining the first word but changing the rest—to come up with FORCE: Upsetting Rape Culture for their group’s name. “Sort of like ‘a force for good,’” Nagle says. “And we talked a lot about ‘forcing the issue.’”

Their work stayed on a local level until the end of 2012, when Brancato and Nagle got an idea to spoof the women’s lingerie brand Victoria’s Secret. The pair had been making underwear with written messages that encouraged gaining consent during sexual encounters, and were upset to find Victoria’s Secret underwear emblazoned with phrases like “Sure Thing” and “Stop Staring.”

“They were really problematic, rape culture slogans that were teaching young people trying to find their sexual identity that words like ‘stop’ or ‘no’ are for flirting and not for setting boundaries,” Nagle says.

So, she and Brancato hatched a plan, along with the help of a web designer, to hack Victoria’s Secret’s website and put up a page with their own consent underwear—with phrases like, “Let’s Talk About Sex” and “No Means No.” (They would pull a similar prank on Playboy’s website the next year.) The action attracted attention from the likes of The Huffington Post, and even got them an offer to make consent-themed underwear for Walmart, which they rejected.

It all spurred Brancato and Nagle to think big, and they came up with a list of temporary monuments to place on the National Mall. The first was a survivor’s poem, which they floated in the Reflecting Pool, reading, “I can’t forget what happened, but no one else remembers.” The Monument Quilt was second on the list.

Nagle and Brancato made the first quilt squares. “It was intense,” Nagle says. “It was the first time I put into writing in clear, unambiguous terms what had happened to me. And I really needed to do that.”

They asked other survivors to share their experiences online and, along with volunteers, created 70 quilt squares based on their words. Then, with help from leaders in the community, the duo put together a guide to hosting workshops and making squares. Soon, they were sending the guides out all over the country, and word about FORCE and its mission spread.

Jane Brown, president and executive director of the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation in Towson, first heard about FORCE when Nagle and Brancato asked her philanthropic organization for help obtaining studio space. “There’s just something about their passion and very organic community connection,” Brown says. “Hannah and Rebecca’s devotion to their work pulls you in.” The Deutsch Foundation went on to help FORCE find its first space in a building on Greenmount Avenue, and then eventually in the Motor House in Station North.

For nearly three years, parts of the quilt have been displayed at college campuses in Baltimore and elsewhere on the East Coast, and FORCE was lauded for its work. Brancato and Nagle are finalists for the Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize, a prestigious $25,000 fellowship awarded in Baltimore, and they were recipients of a $30,000 PNC Transformative Art Prize this year from the Baltimore Office of Promotion & The Arts. A fellowship from the Open Society Institute has allowed FORCE to gather survivors together to work on public projects.

The work has not been without sacrifice. Brancato, who now teaches at MICA, and Nagle paid themselves only by conducting workshops at universities. While raising a combined $44,000 for the quilt from two Kickstarter campaigns, they put their own art practices aside in favor of FORCE’s work. “It was so consuming,” Brancato says, “but exciting, too, because it was finding a new way that art can have a real impact.”

They also recognized the power of creating a community of survivors who could step out of the shadows to tell their stories, some of which they’d never shared, and realize they were not alone. And as the issue of sexual violence became more present in the media (a much-maligned Rolling Stone article about an alleged campus sexual assault and singer Lady Gaga’s emotional performance at the 2016 Oscars are two diametrically opposite examples), FORCE re-affirmed the need to spread the message that those who experience sexual assault aren’t just female college students—they include men; gay, straight, and transgender persons; the young and the old; people of all races and income levels.

This is part of an important shift in the larger sexual violence movement, says Christopher Anderson, executive director of MaleSurvivor, an organization that provides resources and support to male victims of sexual violence. “We can’t just paint with a broad brush,” he says. “We have to ensure we are assisting everyone who is victimized.”

“When you open the quilts up and put them out, it lets this burden go.”

Anderson, a survivor himself, lauds FORCE’s efforts at inclusivity and the quilt’s use as a therapeutic tool. “Art is a vehicle for change, and when all these images come together, they create a powerful political and artistic statement.”

On a brisk but sunny Sunday morning in April, The Monument Quilt begins to blanket North Avenue. Bundled-up volunteers—everyone from MICA students to members of FORCE’s leadership team—tape quilts to the pavement as cones cordon off two blocks of the roadway. The activity attracts the attention of area residents, who stop to look closer. “What’s this?” a woman asks Nagle, who gives her an explanation. “Ohhh,” the woman says, then adds solemnly, “I’ve known some people this happened to.”

Today is a trial display of sorts, a preparation for next fall when the quilt heads to Washington, D.C. It is the largest showing of the quilt to date. Groups of squares have been displayed at colleges and cities across the U.S.—including on a whirlwind, August 2014 tour that added an Indian reservation and cities such as Chicago to the stops. Right now, the quilt has roughly 1,500 squares, though that number is growing. When at the National Mall for a week next fall, it will stretch over a mile and contain a total of 6,000 squares. That number is intentional—each week, approximately 6,000 people are sexually assaulted in the U.S.

Nagle and Brancato are caught up in the bustle of fielding questions and coordinating volunteers that has become routine, but the North Avenue gathering never loses poignancy. “Every time we have a display, I’ll have at least a little moment where I’m like, ‘OK, this is where I really want to be,’” Brancato says. “The whole environment around it, the way that people are interacting, how people are coming together—it’s literally the world I want to live in. That’s why we’re doing this.”

When the display opens at noon, onlookers appear somber as they walk across the quilt squares. A group rests on pillows in a tent while massage therapists and social workers wait to assist. At a table, teenagers draw on red fabric, presumably creating their own squares.

Melani Douglass, an artist and a survivor who volunteers with FORCE, is viewing the quilt for the first time. But instead of sadness, she says she is experiencing joy. “Seeing so many interpretations of people’s experiences is very triumphant, instead of feeling like a mark of shame,” she says.

Though not instantaneous, a sense of community starts to build. In the moments before mayoral candidates arrive and performances begin, a man tells fellow quilt visitors that his mother was a victim of assault. A woman leans on a friend as she cries. As Brancato said before, experiences are “an invisible burden that we’ve been carrying around with us. When you open the quilts up and put them out, it’s letting this burden go.”

Moments later, a procession of dancers and singers moves along North Avenue, accompanied by percussion. Spectators look up as the song carries on the breeze:

“We are here together, gathered together. You are not alone.”