Sports

Vaulting Ambition

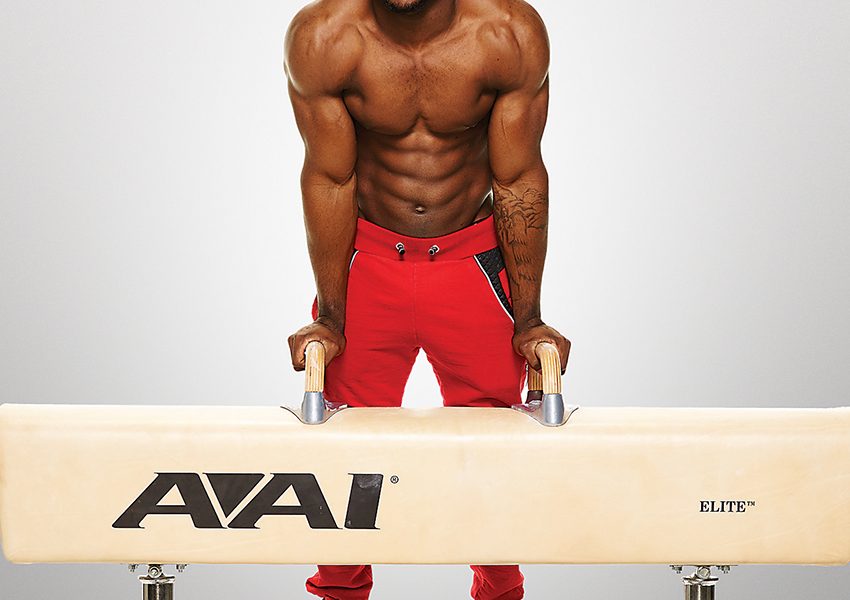

Donnell Whittenburg’s rise as a U.S. national gymnast came quickly. But not easily.

At 4 years old, Donnell Whittenburg was already turning his mother’s Northeast Baltimore duplex into his personal jungle gym. He’d learned to shimmy to the top of the home’s interior doors. If he found a ceiling rod in the basement or a beam above the patio, he’d find a way to climb and swing himself off of those. He mastered jumps and flips from the stairs and living room cartwheels. He wasn’t a boisterous or rebellious child. In fact, Whittenburg was, and remains, quite shy and soft-spoken—just extraordinarily active.

By 5, he was scaling up the side of the house and walking around the dining room table on his hands. His mom, Sheila Brown, remembers him once taking an accidental tumble down a full flight of stairs—in front of guests, no less—only to watch him land on his feet and shrug it off as if nothing happened.

Today, the 21-year-old is a heading to the Olympics as a U.S. men’s gymnastic team alternate. He has been featured in Time and a television commercial with Michael Phelps, promoting the games in Rio de Janeiro this month. Recently, Sports Illustrated ranked him one of the 50 “fittest” male athletes in the world.

But none of this was ever planned. Or even dreamt. His single mother, a career social worker, didn’t know anything about gymnastics when Whittenburg was a little boy. She was simply looking—prodded by his older sister, who was in high school at the time—for somewhere safer than her house for him to practice his stunts when she enrolled him in youth classes.

“I was like, ‘Mom, you have to do something with him,” Latisha Smith, Whittenburg’s sister, recalls with a laugh.

When Donnell Whittenburg burst onto the international sporting radar eight months ago at the World Gymnastics Championships in Glasgow, Scotland, he seemed to have arrived out of nowhere. Whittenburg’s eighth-place overall finish came only after being added to the qualifying field when a Belarus gymnast withdrew at the last moment. Not only did he finish nine spots higher than his closest teammate in the overall standings, he also garnered one of only two U.S. medals won in Scotland—a bronze in the vault—which was his first-ever world championship individual medal.

“I just wanted to come out and do gymnastics,” the powerfully built Whittenburg said with classic modesty. He added that he simply was happy that the men’s team was able “to bring back some hardware.”

Suffice to say, he was disappointed when he didn’t hear his name called for the five-man, U.S. men’s squad after the Olympic trials in late June, but Whittenburg remains excited to go to Rio. At the 2008 Olympics, two U.S. alternates did compete—injuries are a regular part of the game in gymnastics—and he’s still the second-youngest U.S. male gymnast headed to the games this month. “I’m still pretty happy. I get to travel with these guys and be able to support them, and I still have a role to play. I’m still going to train as hard as these guys do because you never know what’s going to happen,” Whittenburg said in a TeamUsa.org interview.

Certainly, the U.S. national coaches recognized Whittenburg’s preternatural ability when they first invited him to train full-time at the team’s facility in Colorado Springs several years ago. What no one could’ve predicted, however, was the accelerated pace of his development in the sport—not to mention his physique—which has filled out to Marvel superhero proportions with the benefit of twice-daily practices and top-flight nutrition. On a men’s squad that boasts a number of Olympic veterans and seasoned, world-class competitors, Whittenburg is considered a rising star alongside Sam Mikulak, 23, the defending U.S. all-around champion.

“He can do things that are kind of unexplainable,” says Mazeika.

“We saw him at the junior nationals and we knew he had an unbelievable upside then, but his progress [since training full-time at the Olympic Training Center] has just been dramatic. Just incredibly fast,” men’s senior national team coordinator Kevin Mazeika says. “He can do things that are kind of unexplainable. Obviously, his strength, which is off-the-charts, is a great strength,” Mazeika continues with a chuckle. “What’s really been surprising is how quick he is.”

Whittenburg clearly possesses a combination of explosiveness and body awareness that is rare—even among world-class gymnasts, Mazeika says. That this comes with a deep desire to improve on the six apparatus that make up men’s gymnastics is even better. “As I got older, mastering the different skills in the various events [rings, vault, parallel bars, pommel horse, high bar, floor] started to intrigue me,” says Whittenburg, whose hobbies include skateboarding and drumming. “Taking them to the next level, refining them, that’s been the mindset for me. It is always a challenge.”

But more compelling than his athletic ability—his catapults off the vaulting horse are as thrilling as anything on display at these Olympic Games—is his back-story. For starters, competitive gymnastic skills, if they are to be acquired at all, require well-trained professional coaches and serious equipment in proper gyms. At elite levels, it’s an expensive sport and traditionally associated with affluent suburban kids. The Northeast Baltimore community where Whittenburg grew up isn’t exactly known as a hotbed of world-class gymnastics.

And not only did his single, working mother have Whittenburg and his sister, Latisha, at home, she had another older daughter, Taneisha, who is mentally disabled, deaf, blind, and mute to care for. Whittenburg, his mother, and his younger sister Latisha—a health care provider who is married with four children today—all refer to Taneisha as “the backbone” of their family. “She’s the one who brought us all closer together,” Whittenburg’s mother says. “Everyone had to pitch in to look after her. Donnell or his sister never complained about any of it.”

As Whittenburg got older and continued to progress, the coaching, gym, and travel costs—not to mention the daily commute to work, school, and practice—added up. At 7 years old, after two years in local youth rec classes, his mother enrolled him at Rebounders Gymnastics in Timonium. By 11, he was traveling to compete in out-of-state meets.

Even at a young age, Whittenburg recognized the challenges his mother faced in supporting his athletic pursuits. After all, it’s not like there is the guarantee of an Olympic medal for anyone, whatever their circumstances. “It was a struggle. Growing up and doing gymnastics was definitely hard financially,” Whittenburg says. “My mom sacrificed a lot, in terms of money and time. It’s just not a cheap sport. But she knew I loved it and would do anything she could so I could keep going.

“I was lucky, too, that my old coach would tell my mother that she could pay what she could, when she could,” Whittenburg continues. “I know he waived the fees sometimes, too.”

That “old coach” is longtime mentor Abdul Mammeri, who coached him at three clubs, including his earliest days with Rebounders Gymnastics, ultimately guiding him to the Junior Olympics where he was initially spotted by U.S. national coaches. A former Algerian national team member, Mammeri remembers seeing Whittenburg at Rebounders during one of the youngster’s first classes and immediately knowing that he wanted him for his club team. Mammeri wasn’t just a former gymnast, he’d also studied coaching for five years at the university level in Algeria.

He became, however, more than a coach for Whittenburg.

“Coach Abdul is absolutely an awesome guy. He’s definitely been a father figure for me,” says Whittenburg, who was estranged from his dad for many years. “He always went out of his way to help me.”

Mammeri recalls the early car rides home after practice when Whittenburg’s mom couldn’t pick him up.

“He wouldn’t talk,” says Mammeri, laughing. “I’d ask him a question and get a one-word answer.”

But, Mammeri says, Whittenburg was fearless from the start in the gym. He also never whined or begged off at practice—unlike many kids, he was always ready to tackle the next skill. “Whether it was something he thought he could do or not, it didn’t matter,” Mammeri says. “He listened and then he’d try. And almost always, he could do the move. Not with perfect or even good technique. That only comes with practice. But he could get his body in the right place.”

The pair became even closer as Whittenburg entered Edgewood High School. By eighth grade, Whittenburg was recognizing his genuine passion for the sport—he’d given up baseball and karate and other endeavors by then—but he’d also run into trouble at the end of that school year. “He got jumped and beaten up badly by four boys in the school bathroom and I had to go see him at school,” Brown recalls. “I didn’t know if it was a gang initiation thing or what, but I was getting him out of Baltimore public schools. I had seen enough as a social worker, and that wasn’t going to happen to him. I did what I had to do.”

Brown used her sister’s address in Harford County to send her son to Edgewood High School where he graduated in 2012. Whittenburg did have a key to his aunt’s house, but nearly every night, his mother left her job to pick him up in Harford County and then shuttled him to Timonium where he trained under Mammeri while she returned to work. Afterward, she’d drive back to Timonium to bring him back to Northeast Baltimore. Her mornings with her kids began every day at 5:30 a.m.

“I lost my father when I was 12, and I would have conversations with his mother, who did an incredible job raising her children,” Mammeri says. “I would say to her, ‘Sheila, please keep him coming to the gym no matter what. It’s going to keep him out of trouble. It will save his life.’”

But Mammeri also was tough on Whittenburg. “I never tell him, ‘It’s good,’ unless it’s good. And he knew that,” Mammeri says. “He’s a champion kid, mentally. You can leave him alone in the gym because he wants to get the job done and knows how to focus.”

After graduating from high school, Whittenburg tried to juggle community college with his training, but it wasn’t working out. When a professor told him he couldn’t afford to miss a week’s worth of school to travel to a meet, Whittenburg reached out to the U.S. national team coaches. They immediately invited him out to Colorado Springs.

Mammeri acknowledges it was hard, but it was time to let Whittenburg go. “I told him, ‘They have the best trainers there, doctors, nutritionists—everything you’ll need.’”

Since then, he has literally taken off.

Whittenburg is one of three gymnasts in the world who have pulled off what’s known as a Ri Se Gwang pike—a one-and-a-half back-flip and full twist vault named after the North Korean gymnast who first performed it in competition in 2009. Only one other vault is judged more difficult.

The vault, rings, and floor exercise are Whittenburg’s best disciplines, followed by the parallel bars, pommel horse, and high bar. At the P&G Championships in June, he lost his grip on the high bar and fell after leading the meet early. But he rebounded, won the gold in the vault, and ultimately finished fifth overall.

For all the pressure that the Olympics bring to bear, Whittenburg doesn’t believe he’ll be overcome with nerves or anything like that if he gets the chance to perform.

He mentions that growing up with someone with disabilities, for example, helps provide an appreciation for life and its experiences. “You understand that something like having a disability could happen to anyone,” he says. “It puts things in perspective.

“I just want to go and compete,” he says of Rio. “I want to feel comfortable. I want to do good routines. Whatever happens after that, happens.”

Meanwhile, his mother is a different story. She and her son may share many qualities, but personality-wise, they are night and day. She’s outgoing and talkative, and on the outside, at least, the much more anxious of the two.

Maybe it goes with being a mother.

“Oh, you can’t find me when Donnell’s turn comes,” Brown says. “I can’t stay in my seat. I’m up. I’m walking around the stadium.” And if her son gets the opportunity to compete in Rio? “Those television cameras shouldn’t even bother looking for me.”

Other Maryland Olympic Athletes

Swimming

Jack Conger, Rockville

Katie Ledecky, Bethesda

Michael Phelps, Baltimore

Chase Kalisz, Bel Air

Basketball

Carmelo Anthony, Baltimore

Angel McCoughtry, Baltimore

Canoe/Kayak

Ashley Nee, Darnestown

Cycling

Bobby Lea, Easton

Sailing

Joe Morris, Annapolis

Triathlon

Katie Zaferesm, Hampstead

Volleyball

Aaron Russell, Ellicott City

Wrestling

Helen Maroulis, Rockville

Kyle Snyder, Woodbine