A Cut Above

Local butcher shops are the newest extension of the farm-to-fork movement.

Benjamin Frey wants you to see the sausage being made.

The process, which begins with a 240-pound whole hog and ends after its ground meat is mixed with spices and squeezed into pig-intestine casings with a hand-crank, unfolds in an open kitchen in full view of Frey’s customers. Despite the spectacle, many still wind up buying the Italians, brats, and chorizos he churns out on a weekly basis.

At John Brown General & Butchery, the Cockeysville store Frey and business partner Robert Voss opened in December, and a handful of other whole-animal butcher shops that have popped up around Baltimore recently, demystifying an animal’s path from farmer’s field to butcher’s table to retail case to a dinner plate is a major part of the mission. “All you have with your butcher is trust, so to build that trust, it’s important to show every aspect of the operation, especially if you’re doing it the right way,” Frey says. “I’m bringing people closer to their food.”

The display case at John Brown.

Local butchers range in size from small operations like John Brown to larger ones like Parts & Labor, which sells to the public and supplies its sister restaurants—such as Woodberry Kitchen—with fresh-cut meat. The roasts, ribs, and rounds at Bowman’s Butcher Shop in Aberdeen come from cows it slaughters, then ages and breaks down. Many, including The Pigheaded Butcher in Timonium, offer formal demonstrations that have become a kind of can’t-miss food-entertainment.

“It amazes me how interested people are in seeing what we do here,” says Robin Weyand, who opened The Pigheaded Butcher with her husband, Charlie, in September. “The first [demonstration], we had maybe 25 people here. The last one, we had over 50 RSVPs.”

For the squeamish, or more leaf-loving eaters among us, the vocabulary of butchery can be unsettling: skinning, separating, cutting, removing, detaching, carving. Then there’s the sight itself. When a pig or steer arrives at a butcher shop, it looks not like that familiar pork chop sizzling on the grill, but like an animal that has recently met its demise. Which is exactly what it is.

“A lot of people are uncomfortable if their meat doesn’t come in a little shrink-wrapped Styrofoam thing,” says George Marsh, Parts & Labor’s head butcher. “I want people to connect with it, see it, get used to it, get comfortable with it. Everyone’s gotten so desensitized to what meat is and what it looks like.”

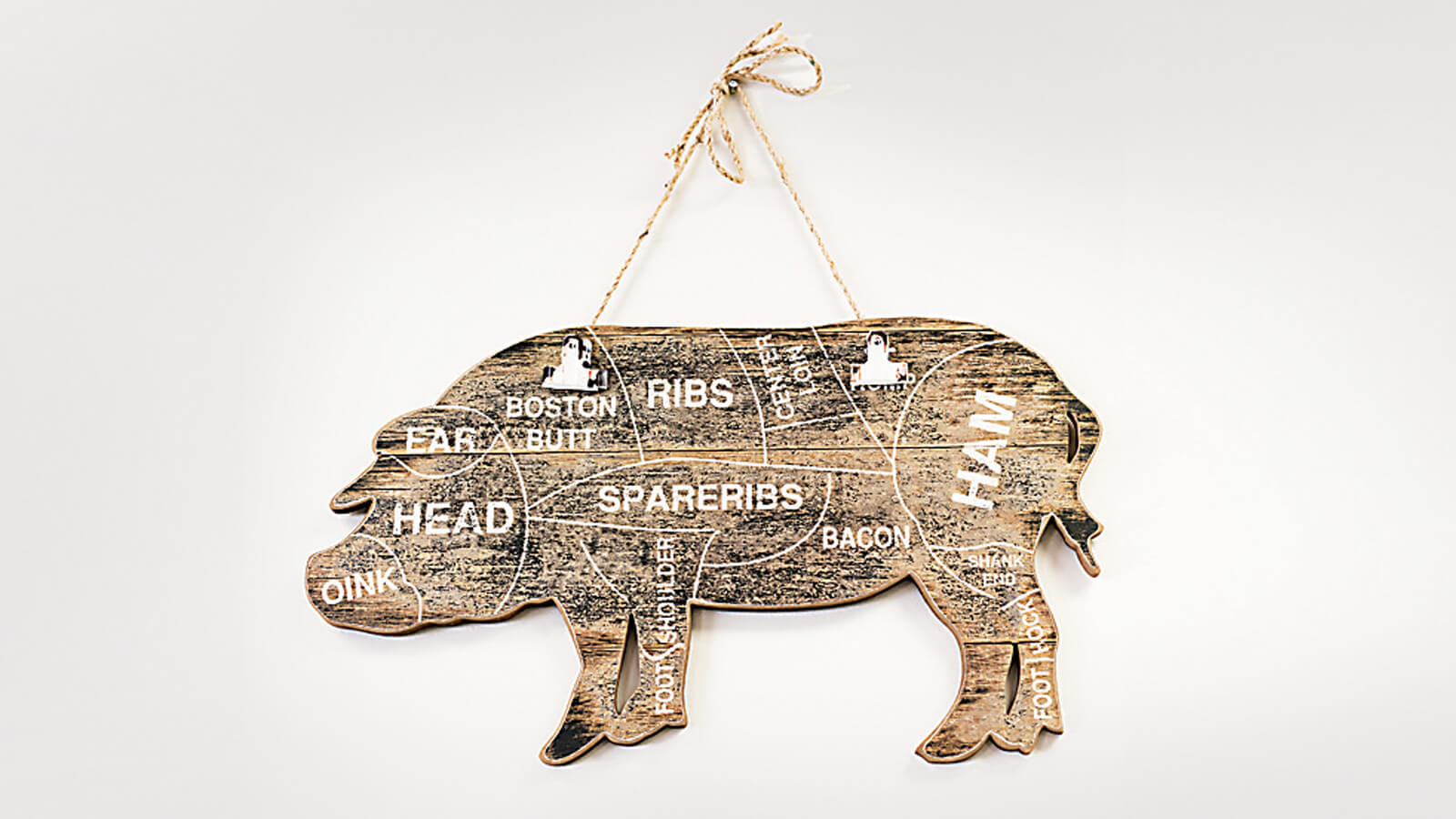

Parts & Labor’s George Marsh at work; a butcher at John Brown; the goods at P & L; the tools at John Brown; anatomy lesson at The Pigheaded Butcher.

For carnivores, the uptick in boutique butcher shops, which source their animals only from local farms, has revolutionized the way they purchase, prepare, savor, and even contemplate meat. The benefits to both the animal and the eater, they say, are numerous. Antibiotic-free, pasture-raised cows, which graze primarily on grass rather than feed (though many are finished on grains to enhance flavor and marbling), enjoy a healthier, happier lifestyle that, in turn, makes them more mouthwatering for the humans who consume them.

“The idea is great, but if the meat didn’t taste different than what you get in the supermarket, eight out of 10 people probably wouldn’t come back,” says Brian Smith, general manager of The Pigheaded Butcher. “We have a product that has a far superior taste and that goes back to the way the animal was raised.”

Since the shop opened, Curtis Adamo has stopped in every Saturday morning like clockwork. The Lutherville resident estimates his grocery budget has increased 10 to 15 percent, an expense he considers worthwhile.

“I would rather spend 10 bucks a pound on high-quality pork shoulder than $1.37 a pound on antibiotic-laden pork shoulder from the grocery store,” he says. “They might as well not be the same animal. The health benefit and the benefit to the animal of being able to grow at a normal pace and have a somewhat better life impact the flavor. The flavor is a really happy byproduct, but a necessary one because it convinces you that you should pony up more dough. Shopping there is like having a relationship with your barber—I leave with a big grin.” And protein for the week.

Under the Knife

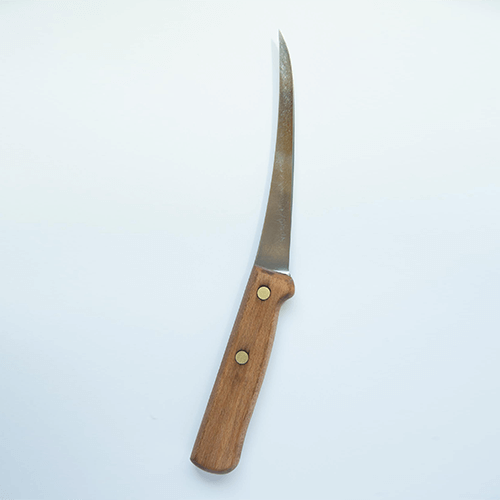

Using the right tools is the key to proper butchering. George Marsh of Parts & Labor sharpens our understanding.

Boning Knife Marsh’s most-used knife. With a sharp point and narrow blade, this tool comes in handy for removing bones and skin.

Butcher Knife With its longer edge, a butcher’s knife is used for cutting fat off large pieces of meat. It’s also good for breaking down beef or pork and dicing sausage or ground beef.

Cleaver“I use one for chopping bones.”

Saw “I try not to use a saw,” says Marsh. “If you know what you’re doing, you can use knives for the whole process. It’s a craft—a dying art that I chose to continue to practice. . . . but sometimes you have to [use a saw.]”

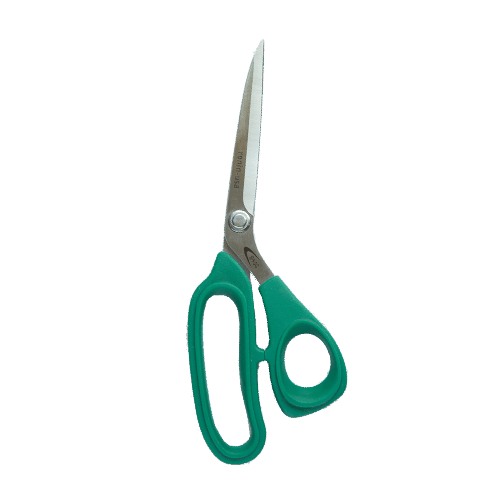

Scissors Marsh uses scissors for everything from cutting cloth and paper to twine and bags.

Water Stones When sharpening knives, the grit of these stones ensures maximum slicing power.

It’s a pig breakdown Saturday at Parts & Labor, and George Marsh is laying out his tools like a surgeon about to perform an operation. Only Marsh’s patient, a 9-month-old crossbred Gloucestershire Old Spot and Duroc, is already DOA.

After sharpening his knives and labeling five plastic bins (meat is sorted based on its fat and sinew content), he carries the 255-pound male from the walk-in to his wooden butcher’s table at the front of the kitchen.

The pigs arrive from the slaughterhouse split and scalded, which removes most of their hair. He uses a boning knife to make the first incision. Marsh practices seam butchery, meaning he cuts through the joints and seams between the individual muscle groups. The tenderloin is the first major cut to be removed, then the ham, then the head, which requires more force. It will be used for scrapple and other products, too. Next, he cuts between the animal’s fourth and fifth ribs. As he works, Marsh fields questions from curious customers, who can watch the process through a window behind the display case. One wants two racks of St. Louis-style spare ribs, so Marsh removes the cartilage, trims the skirt out, and cuts extra meat from the pig’s back. Later, another customer orders a rack of baby back ribs, so Marsh uses a saw to separate them and puts them aside.

Just three racks of baby backs and two racks of spare ribs (from a second pig he’ll break down later) are available. “If I sell all the pork chops out of a pig, that’s it. It’s gone,” he says. “But I always have other options—you just have to be willing to change the game plan. You can always special order, so if you plan a little bit and know you’re going to have people over and want a brisket, I can save you one. But if you come in any day of the week and think you’re going to get whatever you want, it just doesn’t work that way.”

Breaking down a pig is a somewhat physical process, but Marsh is a pro. The knives he uses seem to glide through most parts of the animal, though he changes his grip and stance to cut tougher joints. The process takes about two hours from start to finish.

The display case at John Brown.

Marsh goes on to separate the loins from the belly, and then removes the top of the shoulder, known as the boneless Boston butt. “In the barbecue-competition world, they call this the ‘money cut,’” he explains. “But they’re all money cuts for me. I can add value to every part of this animal. Everything can be cured and turned into something.”

Parts & Labor is one of the few shops that makes fermented sausages such as salami. Because it’s also a restaurant, its business model differs from other butchers. Margins in the retail outlet are much slimmer.

“The challenge is to make sure I can produce things that have a large range of price points—and still make money,” Marsh says. “The first year and a half was really hard financially. We were butchering way more animals than we needed, and it took us longer than it should have to realize that we needed to cut back.”

Meat from small, local farms costs more than meat from large industrial operations in the Midwest and West that travels much farther to Maryland. It is, as Robin Weyand says, “a luxury item.”

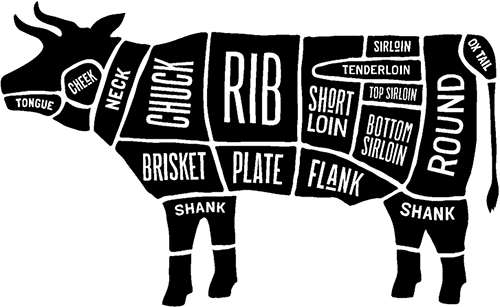

MAKING THE CUT

Charlie Weyand, co-owner of The Pigheaded Butcher, gives us the 411 on unique cuts of meat from a steer.

Teres Major “Similar to a beef tenderloin, but much smaller,” says Weyand. “It’s tender because it sits in the middle of the chuck. I had someone come in three months ago, who took it home and made chili out of it and won a chili contest.”

BAVETTE A cut that comes from the loin. “It originated in France and is now very popular in South America,” says Weyand. “They marinate it and they grill it.”

NAVEL A cut that comes off the rib. “We brine it and cure it and we make pastrami out of it,” says Weyand. Coulotte Steak This cut comes off the top sirloin. “The coulotte is actually the most flavorful part,” says Weyand.

HANGER Steak “There’s only one hanger steak in a steer,” he says. “That’s why they call it a hanger, because it hangs in the middle. All you need to do is salt and pepper it and throw it on the grill.”

At John Brown, house-made beef hot dogs cost $14.99 per pound in mid-June. Compare that to big brand names like Nathan’s Famous or Hebrew National, which routinely sell for less than $6 per pound at Safeway. Its pork chops are $16.99 per pound; Harris Teeter’s are $4.49.

“This is not a cheaper way to eat, and it shouldn’t be billed that way,” says an unapologetic Frey. “I would be one of the people in this industry to tell you that we all need to start eating a lot less meat. And when we do eat meat, we need to eat quality meat.”

While rib-eyes, tenderloins, and T-bones are indeed expensive, many lesser-known cuts like beef shanks, tri-tips, and bavettes provide ample flavor for a fraction of the cost.

“I think we should be killing [fewer] animals and we should appreciate all of those animal parts a little bit more,” Marsh says. “There are tons of things on pigs that are as good, if not better, than bacon. People just haven’t experienced them yet.”

Every other Saturday morning, Michele MacKenzie and her friend, Howdy Long, climb into her Subaru Forester for a 30-minute drive from East Baltimore to Bowman’s, where they stock up on meats. They spend anywhere from $75 to $120 each on staples like bacon, ground beef, and chicken. Long also usually buys a cut of steak he has never tried, while MacKenzie likes to pick up a new variety of sausage. They’ve come to appreciate not only the freshness and flavor of the meat, but their interactions with Alice Schott, who helps run the shop. “If I have questions about how to prepare anything or have any requests for particular cuts, they are willing to accommodate,” MacKenzie says. “They are so knowledgeable and unpretentious. Trust is likely the greatest factor. I trust that what they say is true, and that it really does matter how the animals are treated and where they come from.”

Bowman’s has been in business since the 1940s, when it used the first refrigerated truck in Harford County to deliver meat, Schott says. Each Friday, it kills two cows that it breaks down for its own retail store, which opened five years ago. It also slaughters steers for farmers and for customers who want to buy a quarter or more of the cow.

“We respect the animal and we’re trying to take as much care as we possibly can,” Schott says. “The key for us is the animals being happy, because when they get stressed or they’re worried, they release hormones and the meat can become tough.”

The cows Bowman’s slaughtered the Friday before Memorial Day came from a farm in northern Harford County. They were about 2 years old and weighed roughly

1,500 pounds each. Only 30 minutes or so elapsed from the time they were killed to when each side of beef was hung in a hot box for 24 hours. (After that,

they’re transferred to an aging box for three weeks.) As is standard operating practice, a U.S. Department of Agriculture inspector witnesses every kill,

ensuring each is done humanely and that each cow is free of disease.

On the butcher's block at The Pigheaded Butcher.

Bowman’s is a tiny player in the American beef industry. The documentary Food, Inc. reported that just 13 slaughterhouses process the majority of beef in the United States. The film, along with books by investigative journalists Michael Pollan (author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma) and Eric Schlosser (Fast Food Nation) sparked Americans’ interest in the origins of their food. Baltimore’s butcher renaissance is, in part, an outgrowth of that awakening, Frey believes. “They have brought up important questions, but they don’t really give you answers to those questions,” he says. “In a modern world where we’re all busy people, it could be a lot of work to go to this farm to buy your meat and that market to get your eggs. Being able to house all that under one roof and to do the legwork for people so they know that they can come here and get quality products from local farmers helps answer some of those questions.”

Charlie Weyand’s curiosity led him from a semi-retired life to an apprenticeship at Fleishers Craft Butchery in Brooklyn, N.Y. When he opened The Pigheaded Butcher, he envisioned an old-school shop that would deal exclusively with local suppliers and foster relationships between purveyor and consumer.

Rob Srnec is one of his most loyal customers: He comes in about three times a week, often leaving with meats that he never used to regularly cook or eat. “There’ve been times where I’ve gone in there and asked, ‘What exactly is that?’” he says. “They [say], ‘Come back here and watch, we’re cutting it up.’ You actually see your food in context. That’s cool. You can’t do that at Giant.”