News & Community

Tomorrowland

Port Covington will be like nothing Baltimore has ever seen. But at what cost?

s Mark Rice steps onto one of the city’s new, sleek, black water taxis at the dock outside his company’s manufacturing plant in South Baltimore, he can’t help but gush about the cutting-edge vessel. The 55-foot boat—two similar models are currently in operation, with seven more to follow—comes equipped with WiFi, USB ports beneath every third seat, PowerPoint capability, a weatherproof, flat-screen TV, and cabin lights that can be changed to purple on Ravens game days. With a cool, all-aluminum hull modeled after the classic Chesapeake Bay deadrise fishing boats, it is so deluxe that it is regularly chartered for corporate outings.

The new shuttles—the prototype ran more than $1 million—reach a top speed of 8.5 knots, which is significantly faster than the current 6-knot limit. They stow up to eight bicycles and have a built-in maritime GPS tracking. (Need a lift from Canton to Locust Point on some future Saturday night? Imagine an Uber-like service on the water with an on-demand network of smaller boats.) They deploy fold-down windows for inclement weather and heaters for winter commutes, and carry up to 49 passengers and two crewmembers—although a crew may not be required for long.

“The capability for an unmanned fleet is there,” says Rice, who is leading the taxi tour with Plank Industries executive creative director Marcus Stephens. “The barriers are regulatory, not technical,” adds Rice, whose Maritime Applied Physics Corporation makes both manned and unmanned watercraft for the Navy. “We’d want six months of testing, but that's about it. These water taxis have a lot technology.”

In the midst of City Council deliberations last year over the unprecedented $660 million Port Covington tax-incremental financing request by Sagamore Development—the real estate arm of Plank’s Under Armour empire—another Plank firm, this one called Sagamore Ventures, bought the city’s entire water-taxi operation. Then they announced plans to turn the taxis, previously a tourist attraction, into a state-of-the-art transportation option, inking a 20-year contract with Baltimore officials.

Business & Development

Brand Ambassador

After a tumultuous year, Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank is newly resolved to see his company—and city—thrive.

“We had never made a commercial product of this scope,” Rice continues, as the high-tech boat pushes up the Patapsco River toward Fort McHenry, leaving much of old industrial Baltimore in its wake. “Until Kevin Plank called.”

Later, the vessel turns toward Port Covington, which the taxi will soon start servicing. A massive railroad hub in its heyday, the 266-acre site still looks mostly abandoned from the river. Stephens—he’s the guy who designed Under Armour’s famous interlocking “UA” logo years ago—highlights the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity on the self-contained urban peninsula. He talks excitedly about the possibilities of creating a “live, work, and play” city-within-a-city from scratch, connecting the transformation of the city’s water-taxi system to Sagamore’s aspirations for Port Covington. Like everyone at Plank Industries and Sagamore Development, Stephens is completely taken with the potential of deploying the latest forward-thinking infrastructure—omnipresent wireless connectivity, super-speed fiber-optic lines, multi-modal streets, green architecture, “sensor rich” buildings, soft-shore landscaping—all of which can be installed unhindered by awkward retrofitting.

A rendering of the future Under Armour Campus at Port Covington. RENDERING COURTESY OF Bohlin Cywinski Jackson.

Stephens talks about bringing other concepts to Port Covington, too. Concepts with alien-sounding names like “augmented reality” wayfinding, “frictionless” consumption, and “virtual valet” parking—the likes of which Baltimore has never seen. Most of us think of Baltimore in terms of home or community or workplace, and quirky, historical neighborhoods such as Hampden, Fells Point, Waverly, and Reservoir Hill. But Sagamore’s digital master plan is designed to create a sparkling, smart, tech utopia built around the “city as a service” concept, which takes its cues from the on-demand, “software as a service” model behind Google apps, Amazon web services, and digitized customer relationship management.

Port Covington when it served as a massive railroad hub in South Baltimore. Photograph by A. Aubrey Bodine.

“Port Covington will be nothing like downtown Baltimore,” says Stephens, who plans to visit Songdo, South Korea, a city built from scratch and coined, “The World’s Smartest City.” “There will be ubiquitous connectivity at every interface in Port Covington. Data is everything. Not only will that be convenient, but it will help businesses understand consumer needs and deliver the ‘live, work, play’ experience.”

Sagamore not only plans to install its own redundant fiber-optic network, but also launch its own internet service provider. Company officials envision a Port Covington where a water-taxi trip, bike-share rental (they plan to launch their own bike-share system, too), visit to Sagamore’s distillery or Rye Street Tavern, decision to take in a movie or concert, or shopping trip is curated and integrated into a single experience. Like on a cruise ship. Or at Disney’s Magic Kingdom, as one Sagamore consultant put it, a place where transactions can simply be charged by touching a wristband or card against a touchpoint and are billed to a customer's account.

“I love Disneyland,” Plank told Bloomberg Businessweek last year. “The purpose of Disneyland is to make people smile.”

-

Port Covington: A Brief History

Bounded today by I-95 and McComas Street to the north, Hanover Street to the West and the Patapsco River to the south and east, Port Covington once included a 2,500-car rail yard, a 5-million-bushel grain elevator, a cement elevator, a 1,500-foot ore pier, a 1,000-foot covered merchandise pier, and an intermodal facility for transferring containers to and from rail cars, and various related small buildings.

Tap to Expand

West Covington Park near the City Garage complex.

With Goldman Sachs throwing a $233 million investment into Port Covington, which has recently been touted in Inc. magazine and The New York Times as a serious contender in the Amazon HQ2 sweepstakes, there seems to be every chance the project could surpass the wildest dreams of its most enthusiastic backers over the course of the next two decades. The downside? There is also every chance that it will confirm the worst fears of its toughest critics, further segregating one of the most segregated and poorest cities in the country while becoming another example of trickle-down economic development and exacerbating Baltimore’s persistent income and wealth inequality gaps.

Simply, it is a mistake to frame the long-term outcome as an either/or proposition: As in, either will it create a gleaming new urban landscape that brings thousands of new jobs and new residents to Baltimore as pitched, or it is destined to become an exclusive destination with negligible benefits, at best, for the city a whole and, specifically, disinvested West and East Baltimore.

Most likely, it will do both.

References to Disney and its Magic Kingdom by Plank and Sagamore officials, and phrases like “Dubai on the Patapsco” by others, have not been getting tossed around without reason.

The first phase of Port Covington’s development is a five-year horizon, referred to as “Chapter 1” in Sagamore parlance, with construction beginning as early as next fall. That process includes nine to 11 new city blocks, requisite infrastructure, more than 1,100 new residential units, a 630-room hotel, a million-plus square feet in office space, nearly 800,000 square feet in retail and restaurant development, a 64,000-square-foot entertainment/cinema complex, and an 8-acre waterfront park.

For reference, Chapter 1, which will be built largely on the expansive knoll next to The Sun's printing press, is larger than the whole of Harbor East.

One of the new Sagamore venture Water Taxis.

One of the biggest development projects in the U.S., the final build-out plans call for 47 new city blocks, nearly 9,000 new residential units, at least a half-dozen skyscrapers, a 7,000-seat stadium, and nearly 5 million square feet in combined retail and office space. It is now estimated that it will cost $7.3 billion, including $1.3 billion in public infrastructure funding, and take 25 years to finish. The plan includes 40 acres of parks and, perhaps the highlight for our bay-loving city, 2.5 miles of reclaimed waterfront that Sagamore and Under Armour promise will be accessible to the public.

Meanwhile, the Sagamore Spirit distillery and Rye Street Tavern—call them Port Covington’s “prologue”—are already in place, and the initial response has thrilled Sagamore officials. The distillery, which won’t actually produce its first batch of cask-aged rye whiskey until 2020, has nonetheless attracted more than 9,000 visitors to tour the facility. Next door, Rye Street Tavern, which opened in September and features the food and drink of New York’s NoHo Hospitality Group, including James Beard Award-winning chef Andrew Carmellini, has received rave reviews.

“Realistically, after the first few blocks, everything will be an evolution,” Paff says. “But the heartbeat of the project will remain the distillery and tavern and that campus on the waterfront.”

Walking inside the entrance to city Garage and workers milling about at City Garage in West Port Covington.

A couple of weeks before the mini press tour of the Maritime Applied Physics plant and guided water-taxi voyage (the taxis are branded with a names paying homage to Baltimore history: “Key’s Anthem,” “Cal’s Streak,” “Thurgood’s Justice”), I visited Sagamore’s headquarters in Locust Point for a daylong expedition to all the Plank initiatives already up and running in Port Covington.

The morning began with a slideshow highlighting Under Armour’s success. Baltimoreans know the story by now: From selling perspiration-wicking apparel out of the trunk of his car in 1996, Plank built a juggernaut with nearly $5 billion in annual sales and 15,000 employees around the world, including at its global headquarters here. (Not included in the presentation: Under Armour suffered back-to-back quarterly losses in 2017, and watched its stock price fall 50 percent as Adidas reclaimed the No. 2 spot in athletic shoe and apparel sales behind Nike.)

Taking a coach bus over Hanover Street with Sagamore Development vice president Steve Siegel and Max Oglesbee of the New York-based digital/urban design company Intersection, I got a peek inside three other Port Covington “prologue” pieces—City Garage, The Foundery, and Under Armour’s R&D center, Lighthouse.

Data is everything.”

The Foundery makerspace, which offers metalworking, blacksmithing, woodworking, laser engraving, and textile classes, is impressive, but was quiet on this morning. The incubator complex at City Garage bustled, however. A company called Ready Robotics, spun out of The Johns Hopkins University’s commercial tech-development center, demonstrated a flexible-task robot, which has been trumpeted as the “Swiss army knife of robots.” At the end of the corridor, a Balti Virtual creative team was busy perfecting a Stephen Curry hologram that pops up and starts draining three-pointers when you hold his shoe in your hand. Nearby, another Baltimore company, Bustin Boards, was churning out custom skateboards.

The Foundery Makerspace building in West Port Covington.

Over at Lighthouse, Under Armour’s Batcave of research—no cameras, a waiver agreement, the entire staff in white lab coats—UA employees were digging deep into the science of molded plastics, color reproduction, synthetic fabrics, body scanning, and 3-D printing. These folks picture, for example, a day when the midsole of your running shoe is custom tailored from a scan of your foot, 3-D printed, assembled into a complete sneaker, and then same-day delivered by drone to your rowhouse doorstep.

It is all compelling stuff, except it is not the thing really animating Siegel and Oglesbee. They are each obsessed with hatching a new kind of built environment on the empty slab of Port Covington bordered by McComas Street and I-95 to the north, the Hanover Street Bridge to the west, and the middle branch of the Patapsco everywhere else. Like Stephens, Paff, and others at Sagamore, they have been chasing the latest technological trends around the world, hoping to deliver them to Port Covington. First, Siegel, a 40-something former D.C. developer who worked in economic development for former Washington D.C. mayor Adrian Fenty, talks about the big picture. He references the 42 million cars that pass Port Covington every year on I-95. Those are not just potential targets of Under Armour billboards, but potential Port Covington tourists, visitors, residents, clients—and even employees.

That access to I-95, as well as BWI Airport, Light Rail, Amtrak, MARC, an educated Maryland workforce, and acres of open space, is central to the Port Covington pitch to Amazon, which Sagamore pulled together on behalf of the city. Equally critical, Siegel says, is the allure of other corporate offices, high-end retail, waterfront views, and the ability to attract apartment- and condo-dwelling creative-class millennials—even more so than the (potential) billions in subsidies and tax incentives thrown Amazon’s away. Add to that the hype around 300-mile-per-hour superconducting Maglev trains promoted by Gov. Larry Hogan or, less likely, Elon Musk’s 700-mile-per-hour, vacuum-tube fantasy, also promoted by Hogan, and Port Covington starts to generate genuine buzz.

Inside the Foundery Makerspace.

“Acquiring the land at Port Covington gave Under Armour control of its own destiny beyond the chance to build its own campus,” Siegel says. “Developing a waterfront neighborhood is a bigger opportunity that couldn’t be passed up—and is needed to attract and retain talent in the 21st century.”

If Siegel is obsessed with the macro, Oglesbee keeps his attention focused on more sidewalk-size modernizations. He heralds the digital kiosks in New York City (check LinkNYC) that have replaced telephone booths, offering free gigabyte WiFi, high-speed phone charging, interactive maps, and embedded Andriod tablets, and is anxious to import something similar to Port Covington. He mentions the possibility of a Port Covington-specific “concierge bot”—“like Siri”—that can answer questions about local events, restaurants, shopping, recreation, and transportation options. Like Stephens, he talks about integrated digital-recognition tools that can track a person’s devices, security codes, and preferences as they rent movies in their living room, download music, grab a Zipcar, unlock their front door, or search for take-out pizza or NBA Combine tickets (Under Armour expects to host the combine at Port Covington soon).

“Think about rolling Verizon, Comcast, Apple, and Google into one,” Oglesbee says.

A lot of this stuff is still pie (or rather cloud computing) in the sky. Here is one thing that seems realistic: Utilizing dual-mode, Light Rail car/circulator buses to enhance Port Covington access. A hybrid that can run on rail and road, the vehicle has been used in Japan and could complement the proposed light rail spur. Glow-in-the-dark bike lane technology, first put to use in Amsterdam, is also under consideration, and recently, Sagamore went in front of the city design panel to present their intention to introduce embedded, changeable, high-definition Times Square-type signage to Port Covington.

Siegel, in particular, is a dreamer. He anticipates a transportation future straight out of The Jetsons with Baltimoreans flying in pilotless mini-helicopters to Port Covington. “It is being developed in China,” he says with a smile, looking up from his smartphone. “Look online. Whether it happens or not, we have got to be thinking ahead and make sure we leave room for the innovation from the next generation.”

Local Baltimore company Bustin Boards, which produces custom skateboards at City Garage.

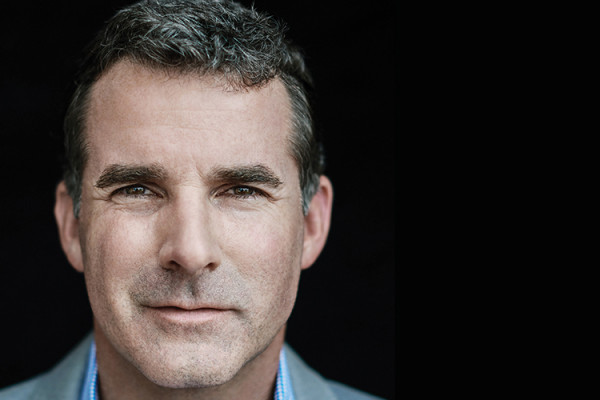

Plank Industries CEO Tom Geddes (L) and executive creative director Marcus Stephens (R).

Years ago, as he watched Under Armour grow at a clip of 20 percent for seven straight years, Plank recognized he needed to expand the company headquarters.

But in 2013, he got word that his efforts to purchase a 7-acre parcel adjacent to their Locust Point headquarters—basically the stretch west toward and including the Baltimore Museum of Industry—fell through after lengthy negotiations with city officials. When Plank got the news, he was in Dubai drinking whiskey with his chief of staff, who thought that maybe it was for the best. The chief of staff told his boss that he thought the property seemed to be a tight squeeze all along.

“I just looked up at the skyline of Dubai, and all I could think to myself was that 15 years ago, that skyline didn’t exist,” Plank recounted to Bloomberg last year. “Until someone with a vision, Sheikh Mohammed, said, ‘I’m going to take this old fishing town and turn it into the economic capital of the Middle East.’ Out of desert and a fishing town. That’s vision. And I’m looking out at it and thinking, ‘Well, what could we do?’”

Siegel and Plank Industries CEO Tom Geddes confirm that story, adding that Sagamore Development was founded soon afterward by Plank and then-Washington, D.C. developer Marc Weller, after Plank had set his sights on the Port Covington peninsula. Weller then secretly began buying up the land. (When it’s mentioned to Siegel that Jim Rouse and his company had secretly acquired Howard County land in similar fashion when they sought to build the economically and racially diverse Columbia from scratch in the 1960s, Siegel notes Walt Disney did the same thing in South Florida.)

Geddes adds that, for Plank, one of the selling points of Port Covington was that the property was essentially empty. “He didn’t want to displace anyone,” he says.

To Plank and Sagamore’s credit, they have studied the best environmental practices as they look to develop Port Covington. Sagamore officials say they intend to raise “sensor-rich” buildings that automatically dim lights in the evening, turn down the air conditioning when an apartment or office is empty, and engineer a cityscape that monitors air and water quality, traffic patterns, trash pickup, and a dozen other things. Solar power, micro-grids, green roofs, modular pavement that helps trees thrive and protects sidewalks, and storm-water management systems that repurpose rainwater to cool buildings and flush toilets are all on the table. And those water taxis? They have less than half the carbon footprint of the old staid blue and white fleet.

Sagamore would also like to see Port Covington buildings share combined heating and air-conditioning plants for greater efficiency. Local environmental firm Biohabitats is creating a water-filtering, soft-shore (non-concrete) interface where the Patapsco River meets the land. A trash wheel at the mouth of the Gwynn Falls to collect debris, like those positioned at the Inner Harbor and in Canton, is in the works, too.

“But we don’t want to be thinking just in terms of efficiency and conservation—or even sustainability. What are the possibilities if we start thinking in terms of regeneration?” Paff asks rhetorically.

The question Paff poses is compelling for a brownfield such as Port Covington and for water as dirty as that around the harbor.

But when Baltimore activists and progressive leaders consider what a sustainable or regenerative neighborhood—and by extension, city—looks like, they are thinking in broader terms than environmental issues.

“Port Covington is not an island unto itself,” says Councilman Zeke Cohen, adding that he hopes the project has a positive impact. “What happens in one part of the city affects the whole.”

Inside City Garage in West Port Covington.

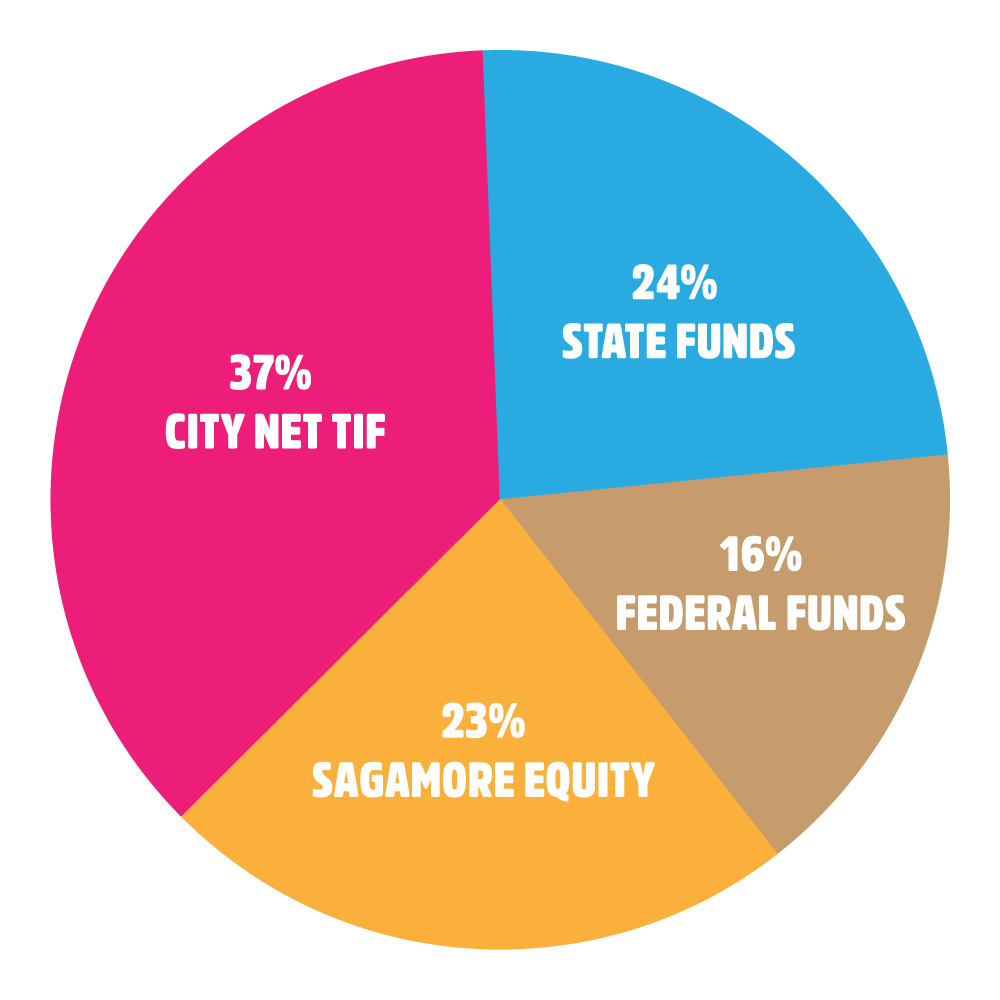

The controversy around the Port Covington financing deal began with the idea that a billionaire, Plank, had requested a gargantuan start-up loan and financial package from the citizens of Baltimore. In fact, he got the third-largest tax-increment financing (TIF) deal in U.S. history. Although the TIF money would be used for “horizontal” infrastructure—streets, pipes, and parks—rather than new Under Armour offices or a Sagamore hotel, the project was conceived to propel Under Armour’s expansion, which has come to a halt. Since the agreement was signed, Under Armour has laid off employees in Baltimore—a far cry from the 10,000 new “teammates,” in UA parlance, that they projected to move to Port Covington.

Beyond the TIF agreement, the Port Covington project is eligible to receive roughly $760 million in tax breaks because it sits in an area the city and state have designated as impoverished. Sagamore has also requested nearly $600 million in state and federal infrastructure funds.

An analysis by MuniCap, a public finance consulting firm hired by Sagamore, reported that Plank and his investors would earn $400 million more on the development with TIF financing than they would without.

“A lot of people were upset and frustrated, including myself, that one year after the death of Freddie Gray and all we’ve seen in the aftermath, following the decades of disinvestment in black and brown neighborhoods, city leaders would respond by offering $660 million to one man, Kevin Plank, and his personal project,” says Charly Carter, executive director of Maryland Working Families. “This is about the blending of Under Armour, Plank Industries, Sagamore, and his personal wealth, which is very problematic. It is poor communities—white, too, but mostly black and brown—subsidizing rich developers while our neighborhoods are left to fall apart. It’s the new Jim Crow.”

Carter was also outraged by Plank’s and Sagamore’s aggressive marketing campaign, which included a half-million-dollar ad buy on local television and not-so-veiled threats that Under Armour would go elsewhere if the TIF deal was not approved quickly by the City Council last September. (It is notable that the council that was expected to be overhauled in the November ’16 election—and indeed was—by a more progressive incoming class less likely to embrace a corporate subsidy of that magnitude.)

Quick explanation: A TIF is shorthand for a loan given to a developer, created by the sale of municipal bonds to private investors, which is recouped over the ensuing decades by the property taxes generated by the new development. Essentially, it is a closed funding loop that is cast as cost-neutral for municipalities. Except that has not always been the case—often far from it—when looked at more holistically.

In 2011, California Gov. Jerry Brown dissolved the state’s redevelopment agencies and ended the TIF program because the state was in debt and needed the revenue that was being lost after decades of TIF use. In Chicago—which, like Baltimore, is a city beset by racial segregation, a public-education crisis, and violence—TIF financing, in vogue since the mid-1980s, has become increasingly controversial. In recent years, nearly half of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s $1.3 billion in tax-incremental financing has gone toward improving the central business district rather than blighted neighborhoods that the program was initially intended to help.

A rendering of a future Port Covington streetscape. RENDERING COURTESY OF SAGAMORE DEVELOPMENT.

In Baltimore, where roughly 50 percent of all the city’s revenue comes from property taxes, even the most optimistic projections predict Port Covington will not contribute property tax revenue to the city’s general fund until 2039—even as the site will need substantial city resources over the next 20 years. Transportation advocates argue that public dollars for a new Light Rail spur could be better spent on first improving the city’s struggling bus system. Public schools can also suffer, if inadvertently, from TIF math.

As The Sun’s Luke Broadwater has reported, local tax breaks and other, smaller-scale TIFs have led to the loss of tens of millions of dollars in state education funding for Baltimore. That is because state contributions to public school systems are based on an algorithm that takes into account the property values of a given jurisdiction—incorrectly assuming all private property is being taxed locally. Baltimore’s shining new buildings appear to be adding to the city’s wealth in the eyes of the state, but, in truth, many have added little to the city’s treasury. At the moment, the State Department of Education is reviewing its school-funding formula. The good news is that, at least for the next three years, the state has agreed not to cut contributions to Baltimore schools.

The overarching problem, says Carter, who previously served as director of the Office of the Public Advocate under former mayor Tony Williams in Washington, D.C, is that the city doesn’t have a clear vision, process, and set of standards for making deals when approached by developers. “These conversations are done behind closed doors with the Baltimore Development Corporation,” Carter says, referring to the city’s nonprofit economic-development agency. “There needs to be sunlight on the process.”

Lawrence Brown, a professor of community health and policy at Morgan State University who is opposed to the Port Covington TIF and tax breaks, points to Baltimore’s long record of redlining and inequitable public investment. He notes there is no fair-housing mandate and no promise—just goals—for living wages in the Port Covington package. Sagamore’s residential units, mostly studio and one-bedroom apartments, are expected to average $2,200 per month, with condominiums costing $350,000. (Initially, no family housing, schools, civic buildings, places of worship, or police or fire stations were included in Sagamore’s master plan.)

“It is one more example of the city investing in ‘the white L,’ where the wealth is concentrated, and not the ‘black butterfly,’” Brown says. “This TIF will exacerbate the racial segregation that already exists. Wealth and capital flow up, towards each other.”

Outside Rye Street Tavern; and Inside Sagamore Spirit.

Developers play an outsized role in shaping the direction and fortunes of the city, acknowledges former city councilman Carl Stokes, who voted for the Port Covington project. “These projects—like the one at Harbor Point, which I was against—by the time they come to the council for a vote, it’s thumbs up or thumbs down,” Stokes says. “If there are too many thumbs down, then it’s just a matter of negotiating around the edges. I have never seen one voted down.”

Another former councilman who voted for the project, James Kraft, predicts Port Covington will become “an extension of the Gold Coast,” referencing expensive, exclusive new developments swinging around the harbor from Canton and Fells Point to Harbor Point, Harbor East, and Locust Point. Kraft says the political clout behind the project, including support among the council, prevented a longer look at the plans. He says he voted yes out of “councilmanic courtesy” for South Baltimore council member Eric Costello, a huge booster of the project.

Under Armour’s Port Covington project is also an example of the increasing influence corporations have on city planning—and not always to good effect. Amazon’s efforts to create a boomtown in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood have fallen worse than flat, contributing to traffic problems, higher rents (up 64 percent since 2010), and greater homelessness in the city.

It is beyond question that South Baltimore, where 20 percent of the population lives below the poverty line and the unemployment rate is 12 percent—similar to citywide figures—could use an influx of jobs. But Baltimore residents are expected to fill only a third of the 25,000 permanent full- and part-time jobs projected for Port Covington. Instead, many of the employees will come from nearby counties. “Baltimore County and Anne Arundel County are jumping for joy over Port Covington,” Carter says. Developers must ensure construction workers earn at least $17.48 during the TIF build up, but there’s no guarantee other employees would earn a living wage. Baltimore’s hourly minimum wage right now is $8.25 and hits $10.10 in 2018. Mayor Catherine Pugh vetoed a $15 minimum wage bill this year. A living wage for a single adult with a child in Baltimore is $27.68.

A rendered map of the entire Port Covington project. MAP COURTESY OF SAGAMORE DEVELOPMENT

At the same time, Sagamore did sign a precedent-setting agreement that will provide $10 million in baseline funding to boost the six South Baltimore communities surrounding Port Covington over the next five years. It will also generate more than $19 million to the coalition known as the SB6—Westport, Brooklyn, Curtis Bay, Lakeland, Mt. Winans, and Cherry Hill—over the first 20 years of the development and provide more than $10 million over five years to fund citywide programs related to youth, education, and empowerment.

“That $39 million will help keep those communities from collapsing,” says Keisha Allen, president of the Westport Neighborhood Association. Sagamore officials, she adds, “have been great to work with.” Still, Allen is concerned about how the people in those neighborhoods, many of whom rely on public transportation, can get to promised jobs in Port Covington.

“It is across the water from Westport, but it is not accessible,” she says. “We’re detached. There is the swing bridge, and they’re looking to make that a pedestrian/bike bridge that links to Westport to Swann Park. There is no money yet. The city needs to fix the holes in the Hanover Street Bridge, too.

Keisha Allen, president of the Westport Neighborhood Association.

“We have old and out-of-date infrastructure throughout lower South Baltimore.”

She is also concerned about speculators and gentrification pushing up property taxes and rent in neighboring communities, displacing seniors and others. “We have families that have been here for generations,” Allen says. “My family has been in the community here for 50 years.”

“Look at what happened with Harbor Point and Perkins Homes,” she says, pointing to the TIF-financed project underway in Southeast Baltimore. That developer, Michael Beatty, used nearby Perkins Homes income figures to win support for its TIF application, then benefitted when the city decided to move the housing project elsewhere because the land had become too valuable.

In a perfect world, Allen continues, “there would be mixed-income housing built in Port Covington and they would feel like our neighbors. We could use the retail and leisure and sports activities in this area,” she says. “But I’m not sure a kid from Westport or Cherry Hill is going to be comfortable fishing over there when it’s all done.”

In this best-case scenario, Allen says, some people in Westport and the SB6 communities find meaningful employment in Port Covington and acquire equity in their homes and younger families move in. “But it’s tricky,” she adds. “We already have speculators here buying houses. And they'll let them sit vacant until the property value rise enough that they can rehab and flip them.”

Her worst fears?

Port Covington becomes the city of the future that leaves too many stuck in the past.

“The communities in South Baltimore have their own plans that they have been working on and want to see implemented and supported by the city,” Allen says. “Westport and other communities have been ignored for too long. I don’t want to see those plans pushed aside or overridden. My hope is that Port Covington complements the surrounding communities and the surrounding communities complement Port Covington.”

But after watching earlier plans to develop Westport go under in the 2008 financial collapse, and witnessing a Walmart and Sam’s Club development effort fizzle in Port Covington, she’s also concerned Plank’s fantasia won’t quite live up to expectations. The real “Tomorrowland” built at Disneyland in 1955 was intended to represent the future—then 1986—but struggled from the outset to keep pace with an ever-changing world.

In that scenario, Allen says, “The jobs don’t come and the infrastructure work that we need done in South Baltimore doesn’t get done. That community-benefits package gets shortchanged.

“All that money gets spent and it doesn’t pan out.”