Food & Drink

Old Salt

A seventh-generation salt business makes its mark in Baltimore.

Nestled between the majestic mountains of West Virginia’s Kanawha Valley and Kanawha River and just down the street from Booker T. Washington’s boyhood home, an unassuming white PVC pipe protrudes from the ground. Amidst the tall blades of grass in this verdant valley, it’s nearly invisible. The only suggestion that it might be something of note is a derrick, once used in drilling deep substratum brine, and now standing decoratively over the pipe.

This opening in the earth—a well from which brine is pulled—serves as a symbol of past and present, reaching 350 feet down toward the 500-million-year-old Iapetus Ocean. It represents the last of the local salt makers in Malden, an area once so prolific in its production that it was known as “the salt-making capital of the East,” with more than 50 salt makers in the mid-1800s and three million bushels of salt produced in a year at its height. (At the World’s Fair in 1851 in London, Kanawha salt was deemed the “best salt in the world.”)

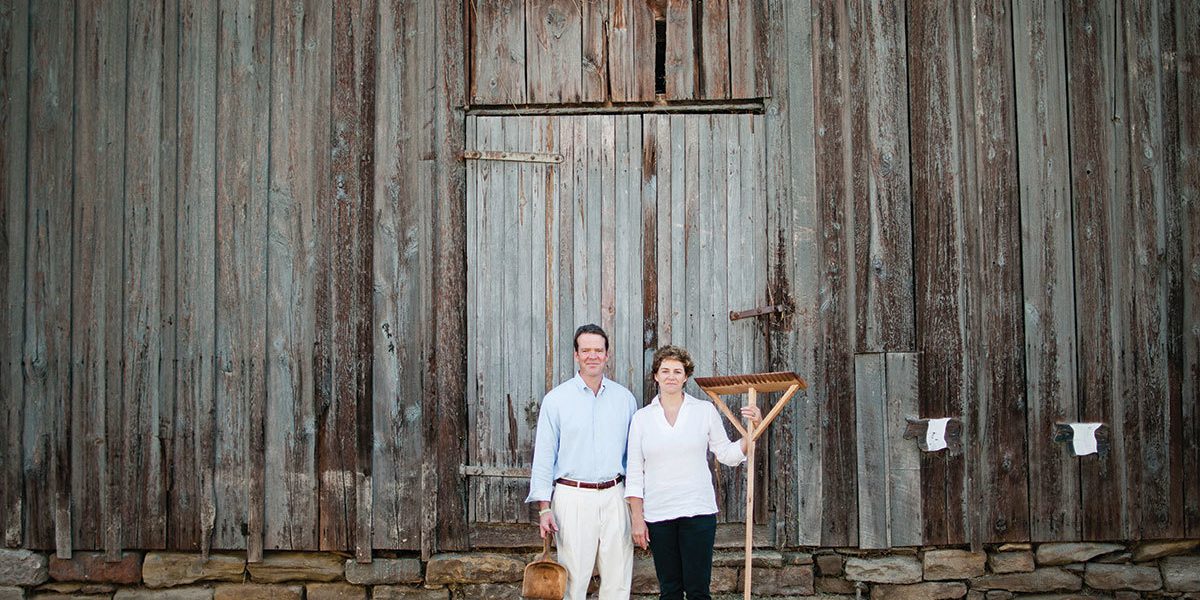

The well sits on the property of J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works, a family-run business that hand harvests the salt trapped between layers of sandstone in the heart of the Appalachian Mountains. It also became an emblem of the company’s renewal and revival, when four years ago, the seventh generation of Dickinson family members decided to bring back the business, giving J.Q. Dickinson the distinction of being the oldest operating salt works in the state. “It’s an amazing feeling when I come to this farm every day to work,” says company co-founder Nancy Bruns, who established the business with her younger brother, Lewis Payne. “It’s like coming home. It’s being enveloped by your heritage, and it’s powerful to know that we’re doing something that’s successful based on what our ancestors did.”

On a hot, humid, overcast day—far from the ideal environment for the solar evaporation salt-making process—Bruns and Payne are hard at work on their family’s 200-year-old farm, about 10 miles from where they grew up in Charleston. Bruns is a classically trained chef who formerly owned a restaurant in Highlands, North Carolina; Payne and his wife, Paige, who also works for the business, spend summers working the land in Malden, though the Paynes live part-time in Baltimore so that their son, Davis, can attend The Odyssey School in Stevenson, while their daughter, Cameron, boards at St. Timothy’s School—Bruns’ alma mater, which is also in Stevenson.

There are other Baltimore ties, too. Though J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works is some 364 miles away, Malden counts as local when it comes to sourcing salt. From the J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works, on the site of a former garden center, 450 pounds of salt are stacked in recycled cardboard boxes bound for Baltimore. Lying in wait, behind a burlap curtain, the boxes, 25 pounds each, hold bags of salt that Woodberry Kitchen’s James Beard Award-winning chef, Spike Gjerde, will use as a key ingredient for his Snake Oil hot sauce. (In the week that follows, Bruns will make the six-hour drive to the Woodberry area to deliver the salt herself to save on shipping costs.) It is the salt that Gjerde uses exclusively at Woodberry Kitchen, Artifact Coffee, and Grand Cru. (He also uses it at Parts & Labor, though not exclusively.) In total, he buys 1,420 pounds of cooking and finishing salts a year from the company. “Over time, we’ve been able to shrink the ingredients that were from nonlocal sources at Woodberry,” says Gjerde. “But I never really dreamed we’d be able to do that with salt. Before J.Q. Dickinson, I was importing sea salt from Italy.”

At work on the salt beds; storing the salt; Dickinson descendants reunite on the family farm in the Kanawha Valley; salt relics from the property.

While the salt is sold at some of the most celebrated kitchens in the country—Husk in Charleston, South Carolina, and The French Laundry in the Napa Valley—Baltimore is a major market for J.Q. Dickinson salt. Its finishing salts sit on the shelves at Trohv in Hampden, E.N. Olivier on Falls Road, Juniper Culinary Apothecary in the Mount Vernon Marketplace, and The Chesapeake Wine Company in Canton. The salt is also sold at MOM’s Organic Market in Hampden, as well as The Pigheaded Butcher in Timonium, and John Brown General & Butchery in Cockeysville. It’s the salt you taste when you buy a bar from Eldersburg-based Salazon Chocolate Co.

In America, there are a handful of salt makers, from Maine and Long Island to Oregon. But Dickinson salt is the only salt in the Northern Hemisphere drawn from an aquifer, which is permeable rock that has water running through it. “People ask me all the time, ‘Isn’t salt just salt? What makes yours different?’” says Bruns. “Our salt differs from other salts in the way that you think of anything else that comes from the earth. If you grow Pinot Noir grapes in California, New Zealand, or France, they’re going to taste different because of the soil and their terroir. I think of salt in the same way. Our salt is coming from underground and running through lots of rocks, and so it’s gaining all those minerals. And the minerality of our salt is different than the minerality of any other salt.”

Malden was once known as “the salt-making capital of the East” with more than 50 salt makers.

Move over Morton—sea salt is hotter than ever. (In recent years, even Wendy’s changed its fry recipe for the first time in decades, adding sea salt to the spuds.) As consumers and retailers have discovered the ways in which sea salt can elevate flavor—contributing coarseness, crunchiness, and boldness—the market has soared. The gourmet salt market is expected to reach $1,340.9 million globally by 2019, according to Markets and Markets global market research and consulting company.

Unlike salts such as Himalayan salts and Morton Salt that are mined from mountains and employ additives to keep them from caking, J.Q. Dickinson’s salt is said to be superior. “It’s pure and has young, open crystals that add a lot of crunch and flavor and make the food more interesting,” says Liz Nuttle, owner of E.N. Olivier. “The finishing salt is very special,” concurs Gjerde. “It’s distinct from any salt I’ve ever tasted. It doesn’t have the same intense attack on the taste buds. It has a softness that I attribute to the higher presence of other minerals and is one of the reasons you can add it to the end of cooking. The size and shape of the crystal makes it an incredible complement to the food we make. I always have it in my bag when I travel.”

Salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl on the chemical compound chart), is a naturally occurring material and an essential element in our diets. According to the CDC, each day the average American consumes about 3,400 milligrams of salt, which might be mined from the earth or harvested from the sea. “It’s the only condiment produced on every continent and the only thing humans crave, because we need it to survive,” says Nuttle.

Salt has played an important role in world history and been a prized possession, dating as far back as 6050 B.C. Roman soldiers were given an allowance of salt know as salarium, from which the word “salary” is derived. It’s also been used in religious offerings in Egyptian culture and, at one time, was one of the world’s most sought-after commodities for trade. Even the Phoenicians were known to trade salt. “Salt dates back to the earliest civilizations of Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent,” explains Carter Bruns, Nancy’s historian husband who happened upon the history of the family’s livelihood while pursuing a master’s degree in history at Western Carolina University. “As soon as man started settling in cities and stayed in place to preserve food, there was salt.”

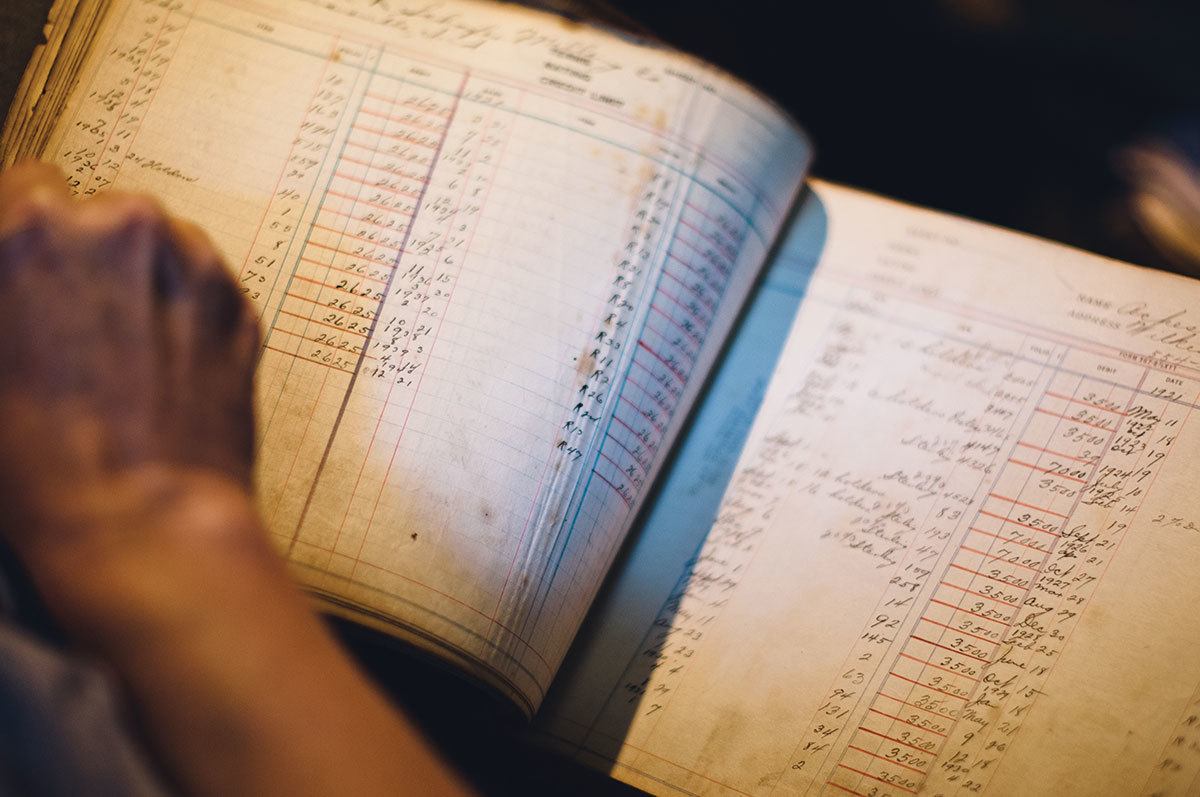

The finished product; an heirloom ledger in the old saltworks offices; at the end of the evaporation process, salt is raked and gathered to get ready for sale; vintage salt jars. —Photography by Michael Marion

J.Q. Dickinson’s story starts in the early part of the 19th century when William Dickinson, along with his brother-in-law, Joel Shrewsbury, traveled from Bedford County, Virginia, to the rugged Kanawha Valley to find brine. Using hollowed-out sycamore trees as piping, Dickinson and his crew made their first salt well. Though Bruns and Payne use solar evaporation methods now, Dickinson and the generations that followed boiled the brine, which led the family to run and own other industries in coal, gas, and timber, holdings they still have today. By 1817, at a time before refrigeration, business was booming as barrels of salt were loaded on barges bound for Cincinnati, then the seat of the meat-packing industry, where the salt was used for curing and preservation, then, years later, for road construction and paving.

“We grew up in Charleston, but we didn’t know anything about the salt-making that went on here,” says Payne, the great, great, great, great grandson of William Dickinson.

Ironically, Bruns’ discovery came when Carter stumbled upon a wealth of information about the Kanawha Valley while writing his master’s thesis. “We would make fun of him on trips, because he always had these historical books,” Nancy recalls. “And one time, he brought Mark Kurlansky’s book Salt on a trip. He said, ‘You all make fun of me for reading these books, but your family is in this one.’ I was like, ‘Really?’ We grew up here, but we didn’t know the history.” Recalls Carter, “After learning the family’s history, she said, ‘Honey, do you think there’s still brine?’ And I told her that I had no doubt,” recalls Carter.

At the time, Bruns couldn’t shake the idea that she and her brother should attempt to bring the business back to life. “I was seeing more and more salt companies pop up, and it just kind of struck me,” she recalls. “I was like, ‘We have the land, the resources are there, and the timing is right where consumers and chefs are trying to source at home.’ There are just a handful of salt companies in this country—I saw a niche market.” With some gentle prodding, Payne agreed. Says Payne, “It took the second or third discussion to wrap my brain around it.”

Bruns couldn’t shake the idea that she and her brother should bring the business back to life.

In May of 2013, the siblings hired a water-well driller to bore a hole for brine. “We didn’t know what it was going to look like or taste like,” says Payne, “or if it was going to be contaminated or even if there was brine.” But with the help of well-preserved maps, which showed the locations and elevations of the wells on-site at the former salt offices still on the property, they had a hunch that they might find salt. “At 300 feet, which is what the maps told us, we hit saltwater,” says Payne. “We felt the deeper we go, the richer the brine is going to be.” At 350 feet, they hit pay dirt. “We were thrilled. We looked at each other and said, ‘What do we do now?’ We thought we might never get to that point.”

J.Q. Dickinson sold about 11,000 pounds of salt last year and expects that sales will stay strong in the coming year. In addition to tapping into interest in local sourcing, J.Q. Dickinson’s all-natural process taps into the sustainable sourcing trend, too. While most salt is mined with machines and then highly refined to remove impurities, J.Q. Dickinson relies solely on Mother Nature. “Only a few salt makers in the country were doing this through evaporation with salt water and noncooking methods. When we started a few years ago, Maine Sea Salt was the only one,” explains Payne.

The process unfolds over four to six weeks in one of two tanks that “clarify” and allow the iron in the salt to oxidize, then settle. It’s then moved into evaporation beds in one of four sun-houses. From there, the salt is evaporated to concentrate the salinity, before being pumped into the final crystallization beds, where the crystals are raked to separate them from the nigari (a mineral-rich liquid and naturally occurring byproduct of the salt, that can be used to make tofu). New beds are poured March through October.

The salt is a sight to behold. Against the black polyethylene-lined beds, the small, shimmering pure-white pyramid- and diamond-shape crystals float on the water like stars dotting the sky. “It’s important for a food product to be as clean and sustainable as possible,” says Bruns. “I think of the salt as an agricultural product that’s coming from the ground. We are letting Mother Nature do her work, and then we harvest it.”

Inside the offices, a few feet from the sun-houses, Payne and Paige sift through trays of salt that lay on cotton flour cloth for drying. They use hand-carved birch paddles to deal with impurities such as bugs and other organic matter that might land in the beds. It’s laborious, but it puts them in touch with their past. “Some days you think, ‘It had to be a fairy tale,’” says Payne. “But this brings it back to life. This isn’t just another product on the shelves. It’s something we take seriously, because using that name represents our entire family.”

Worth Its Salt

Most salts are at least 98 to 99 percent sodium chloride, but it’s what goes into that last 2 percent that distinguishes types of salt. Here’s a rundown on how to distinguish your salts.

Kosher Salt: Craggy crystals that come from either the sea or the earth. It’s fast-dissolving and can be used for all cooking.

Fleur De Sel: This sea salt is a special-occasion salt that comes from evaporating ocean water. The fleur de sel is the delicate crystals that form on the surface. Great on crudo or raw veggies.

Flaked Sea Salt: This is one of the fastest-dissolving salt of all grains, the most famous of which comes from Maldon, England. A great finishing salt to use on all foods.

Crystalline Sea Salt: Adds a powerful punch of flavor to anything from a salad to a steak. Depending on what minerals they contain, the crystals come fine or coarse and vary in color.