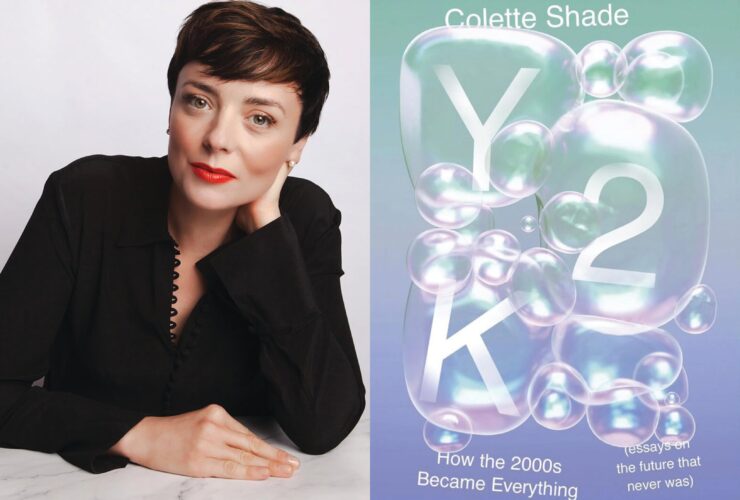

Arts & Culture

Cinema Paradiso

The Maryland Film Festival is no longer a hidden gem. But will it be ruined by success?

Jed Dietz looks surprisingly relaxed. A House of Cards baseball cap perched on his head, the puckish and genial director of the Maryland Film Festival is leading a small tour of the under-renovation Parkway Theatre at North Avenue and Charles Street. It’s January, four months before the Parkway’s grand opening to coincide with the first day of the festival.

Jed Dietz looks surprisingly relaxed. A House of Cards baseball cap perched on his head, the puckish and genial director of the Maryland Film Festival is leading a small tour of the under-renovation Parkway Theatre at North Avenue and Charles Street. It’s January, four months before the Parkway’s grand opening to coincide with the first day of the festival.

The Parkway represents a sea change for the Maryland Film Festival. Now, on top of hosting their annual movie festival and assorted member’s only screenings and panel discussions throughout the year, they’ll be running a full-time independent cinema.

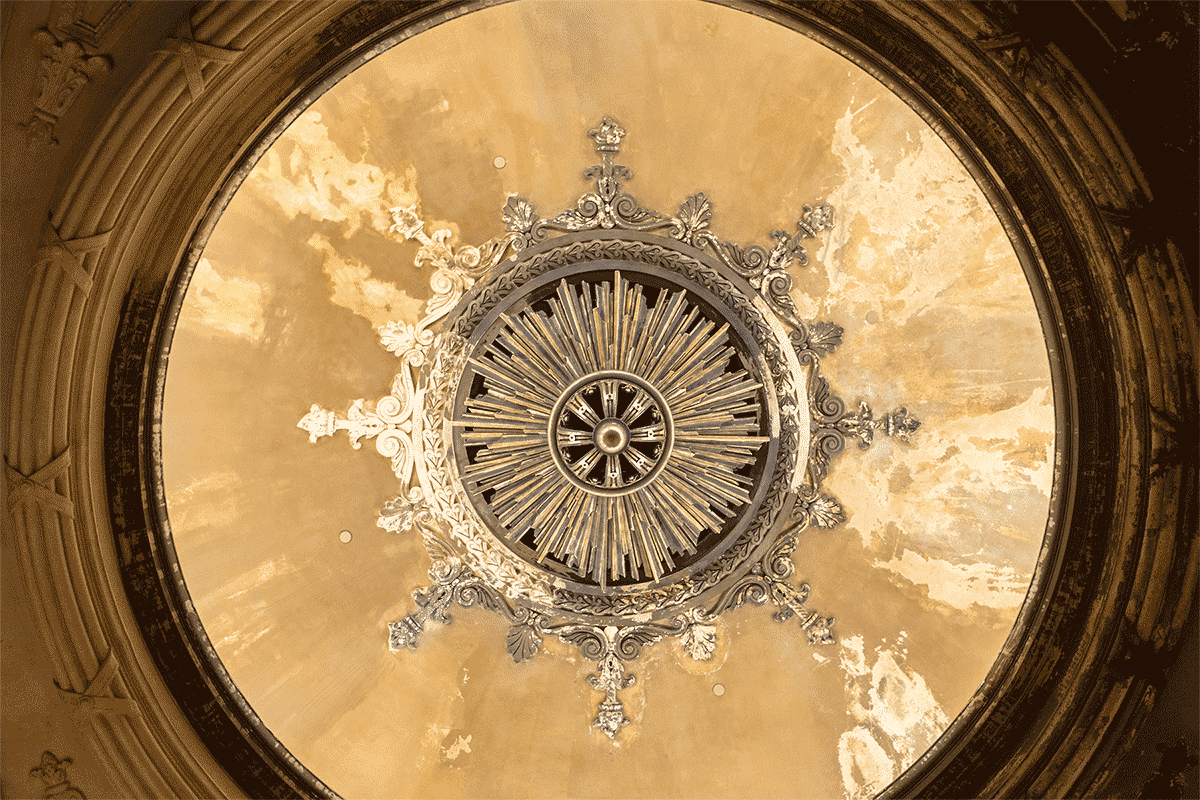

The tour group—composed of a few donors, a handful of educators and nonprofit leaders, and curious film lovers—follows Dietz dutifully past piles of insulation and spools of construction tape into the Parkway’s main theater. It’s an impressive structure, with a domed roof, hand-painted murals, and the kind of ornate plasterwork that was popular in 1915, when the theater was built (it was one of the country’s first theaters built strictly for the display of film).

▶ eric hatch, jed dietz, and scott braid at the new parkway theatre

At this point, there are no seats, there is no stage, and, notably, there is no movie screen. Eventually, there will be a lobby, a small cafe that sells local wine, beer, and food, and two smaller theaters in two adjacent buildings—Dietz hands out blueprints to those who are interested. Still, one has to use a lot of imagination to envision the finished product.

Ed Peres, a former MFF board member who is intimately acquainted with the project, is thrilled with the progress. “No hard hats this time!” he enthuses. And project engineer Matt Novak, who is tagging along with the tour, explains that a lot can happen very quickly. “We make progress every day,” he promises. For his part, Dietz, looking like a proud papa, reiterates his confidence that the theater will be up and running by May.

“It’s going to be great!” he says, then he adds with a chuckle, “Did that just sound like Donald Trump?”

Maybe Dietz does sound a little overly gung ho, but then again, it would be foolhardy to underestimate him—or the Maryland Film Festival.

Here’s a thing you may not know: Every state in America has at least one film festival. Some, like Sundance, Telluride, and Austin, Texas’ SXSW, are brand names. Others have a very specific niche, like, say, San Francisco’s Frameline festival (devoted to LGBTQ film) or Rochester, New York’s High Falls Festival (devoted to women in film). Some only appeal to locals. Some only play documentaries or shorts.

Dietz, a transplant from Syracuse, New York, who ran a film incubation company called Film Development Partners, arrived in Baltimore in 1991 with his wife, Julia McMillan, who had just been hired to run the Pediatric Residency Program at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. He says at the time he was surprised Baltimore didn’t already have a major film festival. He officially launched the Maryland Film Festival in 1999.

One idea Dietz had was to make it a shorts-only festival, but then he decided that scope was too narrow (the festival does do an all-shorts program on its all-important opening night). A few things, however, would make the Maryland Film Festival tick: A representative of the film—usually the director or one of the stars—would have to be present for the screening to be scheduled; the festival would be laser-focused on independent cinema; and the festival would go out of its way to be a nurturing and welcoming place for emerging filmmakers.

There would be other things that distinguished the fest: It wouldn’t be a commercial festival, like Sundance, where pressure is intense and film distributors, trade journalists, and other industry types prowl screenings and parties to get exclusive interviews and make deals. And there wouldn’t be a competition. No audience prize. No jury prize. No prize whatsoever. The festival would strictly be film for film’s sake.

There was another thing the Maryland Film Festival wouldn’t be—and that’s a John Waters festival. Waters agreed to host a screening of one of his favorite films every year (they’ve included films as diverse as Joseph Losey’s Boom! and Terence Davies’ The Deep Blue Sea) and he sits on the board, but he’s not directly involved in the festival’s programming or promotion.

“It’s not my baby,” Waters jokes. “It’s Jed’s baby. I’m just a fan. I go to it and I support it.”

▶ john waters leads a film discussion; Film festival badge; staff and volunteers getting silly on Closing Night

And yet, of course, Waters’ DNA is all over the fest—all over Baltimore for that matter. Baltimore has a particular appreciation for the experimental and the weird. As a result, our film festival audiences are just a little more adventurous than most.

“Maybe it’s because of the John Waters effect,” muses filmmaker Joe Swanberg, a festival regular. “Or an inherent quality in Baltimoreans. They’re the most open audience I’ve ever shown work to. You can’t offend that crowd.”

For his part, Waters says that Baltimoreans have “unorthodox” taste and, more importantly, “humorous taste.”

Over the years, the festival began to grow in reputation, not just among Maryland residents but also among the film cognoscenti.

In 2011, Richard Brody, the famously esoterically minded film critic for The New Yorker, wrote this: “May I be forgiven for thinking that, for the span of a few days, the center of cinematic gravity had shifted from wherever you’d usually look for it (Hollywood, New York, Paris) to Baltimore. . . .”

Brody, who makes a point of attending the festival every year, explains it further over the phone. “It made me feel like I was in the epicenter of contemporary filmmaking,” he says. “And that in and of itself was thrilling.”

▶ the parkway under construction.

Joe Swanberg describes the first time he showed a film at the festival, in 2006, as “heavenly.” He and the other filmmakers showing their work were flown in, put up at hotels, given all-access passes to all festival events, and treated to some other, Baltimore-specific perks.

“Cal Ripken donated his Camden Yards seats to us!” Swanberg says, almost disbelievingly.

It was Swanberg, one of the progenitors of the low-budget, naturalistic “mumblecore” movement, who helped launch the filmmakers’ conference that has become one of the hallmarks of the fest. On the second day of the MFF, filmmakers and invited guests are encouraged to freely share ideas and discuss the challenges they face making and distributing art with generally small budgets. The conversations tend to be freewheeling, intimate, informative. Bloody Mary’s are always involved. This conference is one of the many reasons why the festival is so beloved.

Swanberg points out some other festival high points: The festival’s Station North location makes it easy to navigate. The MFF is unusually convivial, in that unpretentious, Baltimore way. (“It felt like everyone was hanging out together all the time,” Swanberg says.) It’s ideally timed, after Sundance and SXSW but before Cannes. And again, there are those crowds.

▶ Ramona Diaz's Motherland

“They’re down to show up for weirder, smaller movies,” Swanberg says. “They’re not fixated on name talent or celebrities.” Internationally acclaimed documentary filmmaker Ramona Diaz (Imelda), who lives in Mount Washington, has her own special relationship to the festival and its audiences.

▶ local filmmaker ramona diaz

She ran into Dietz at the Sundance Film Festival in 2004 and he invited her to show a film at the MFF. The timing couldn’t have been any better.

She had just moved to Baltimore from Austin that year, and the festival was a way of getting to know her new city better. She jokes that, the first year, she was a “poseur,” faking it when fellow filmmakers asked her for recommendations of what to do around town. Now she’s an expert. “I know all the cool restaurants,” she jokes. What’s more, the festival has connected her to the city. “I’ll be walking down Charles Street or eating at a restaurant and people will stop me,” she says. “They want to talk about my work. They really know it.” She notes that the Baltimore audiences are particularly insightful and engaged. “They’re close watchers. It’s very satisfying and validating to watch one of my films with them.”

Other filmmakers echo her sentiments. “[The MFF] is like summer camp for filmmakers,” says Alex Ross Perry (Listen Up Philip). “It’s the purest expression of what a film festival should be.” He adds, jokingly, that when he and other festival regulars talk about it, “We sound like members of a cult.”

Agrees David Lowery (Pete’s Dragon): “I’m always telling everyone I know that Maryland is the coolest festival around.” The response back when his friends show up? “Yes, it’s exactly as cool as you said it would be.”

To them, the MFF has the feeling of a secret treasure, an indie gem—like a favorite underground band or dive bar.

“It’s really small in the best way,” says filmmaker Kris Swanberg (Unexpected), who is Joe Swanberg’s wife. “It’s just the right size.”

But as the festival continues to grow, and with the Parkway’s imminent opening, is there any worry that the festival might get too successful or—God forbid—sell out?

▶The sunburst is a common motif found throughout the Parkway Theatre, most notably on its domed ceiling.

Those devoted to the fest are surprisingly unconcerned about this prospect.

“I believe in [the MFF],” says distributor Matt Grady, whose Factory 25 has released many films that he first discovered at the festival. “They’ll stick with their roots—the programming of quality films.”

Adds David Lowery, “Knowing Jed and Eric and Scott and knowing their tastes and what they want to do, I just don’t think that would ever happen. I’ve been there seven times. They keep getting better at doing the thing they want to do.”

The Eric and Scott that Lowery refers to are the festival's director of programming, Eric Hatch, and its associate director of programming, Scott Braid. Along with Dietz, they curate every film that plays at the festival.

▶The Parkway under construction.

“As long as one of us strongly loves a film, we will show it,” says Hatch. (A clue: Look to see who writes up the capsule description in the festival’s program guide. That’s usually the film’s champion.) Programming the festival is a full-time job. Submissions are accepted by mail or online—at this point, the volume is so great that they’ve recruited a committee to help screen them—and, during the year, Hatch, Braid, and Dietz attend festivals like Sundance and SXSW, looking for under-the-radar gems. The festival has garnered a reputation for having great taste, particularly when it comes to challenging or avant-garde works.

“The key to any film festival, obviously, is the programming,” says Richard Brody. “And I have discovered remarkable films there.”

“They’re one step ahead of everyone else,” says Joe Swanberg. That’s partly what makes the festival’s formula inimitable. “You couldn’t teach people to have their taste.”

Both Hatch and Braid will program the films at the Parkway, although there will be full-time support staff, as well. Which leads to the next question: Is the Maryland Film Festival biting off more than it can chew?

“It’s definitely a little bit of the Be Careful What You Wish For department,” cracks Hatch.

At the same time, the opening of the Parkway—technically, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Film Center, which, like the festival, will be run as a nonprofit—is the culmination of many years of preparation and a dream come true for the entire festival staff.

At the same time, the opening of the Parkway—technically, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Parkway Film Center, which, like the festival, will be run as a nonprofit—is the culmination of many years of preparation and a dream come true for the entire festival staff.

▶ Ornate scrolls add to the Italian Renaissance look.

There is, however, one venerable establishment in Baltimore that is less than enthused about the Parkway. That is The Charles Theatre, the independent cinema house that is located a mere block away from the new theater. Longtime fans of the festival know that the Charles used to partner closely with the MFF. It was, in fact, the festival’s signature theater and its parking lot served as the festival’s “tent village,” where tickets and T-shirts could be bought, panel discussions were held, and the closing night party took place. All that changed once the MFF started making its plans to open the Parkway.

The Charles severed its ties with the festival, leaving the MFF scrambling for new venues (they ended up spreading the festival all around Station North and Remington, from MICA’s Brown Center to the Single Carrot Theatre). The folks at the Charles say they had no choice.

“The development of the Parkway creates a real problem for the Charles,” admits Kathleen Lyon, who co-owns the theater with her father, James “Buzz” Cusack. “We have some serious concerns about how the two will coexist and remain viable.”

Lyon’s argument is basically that, even with the best intentions, the Parkway will drain customers from the Charles.

But Dietz and co. claim that their model is different. For example, they will program deeper-cut indie films and not “corporate curated art house films,” as Hatch puts it. The Parkway will play films that have a tiny distributor, or perhaps no distributor at all. And they plan to bring something of a Maryland Film Festival vibe to the theater, hosting Q&As and student filmmaker series, and doing lots of grassroots promotion in schools and online. (The Parkway is partnering with the film studies programs at MICA and Hopkins.)

Dietz argues that the Parkway will help create a kind of “film district” in the Station North area and that, if anything, the Parkway could actually help the Charles. “If they’re playing the latest Woody Allen film, we might do a Women in Woody Allen’s Films series,” he says.

Hatch offers another example: “If the Charles is playing Moonlight, we might play Medicine for Melancholy”—director Barry Jenkins’ first film.

Lyon, however, remains unconvinced.

“They’re opening up spitting distance from us with virtually the same programming model we have,” she says.

When asked to weigh in on the debate, John Waters is diplomatic. “I’m not going to make Sophie’s Choice,” he says. “Let’s hope Baltimore supports both.”

▶Workmen contemplate the domed roof of the Parkway.

We won’t know for sure, of course, until the theater opens. Until then, the Parkway has some more immediate concerns—getting the toilets installed, for example.

Two months after the tour of the Parkway, Dietz expresses his trademark optimism. “We’re on budget and on schedule, which is remarkable,” he says. “The biggest things—projection equipment, screens, seats—we’re very confident about. We’re in good shape—but that doesn’t mean we get to take our eye off the ball.”

Mostly, he says he can’t wait to share the Parkway with Baltimore on May 3, when the festival’s 19th season begins. “That’s what I’m most excited about.”

So no concerns at all?

“I have this recurrent nightmare going into every festival that, after all our hard work, nobody comes,” he admits. Then he gives a tiny chuckle. “And then they always show up!”