Arts & Culture

Rock Steady

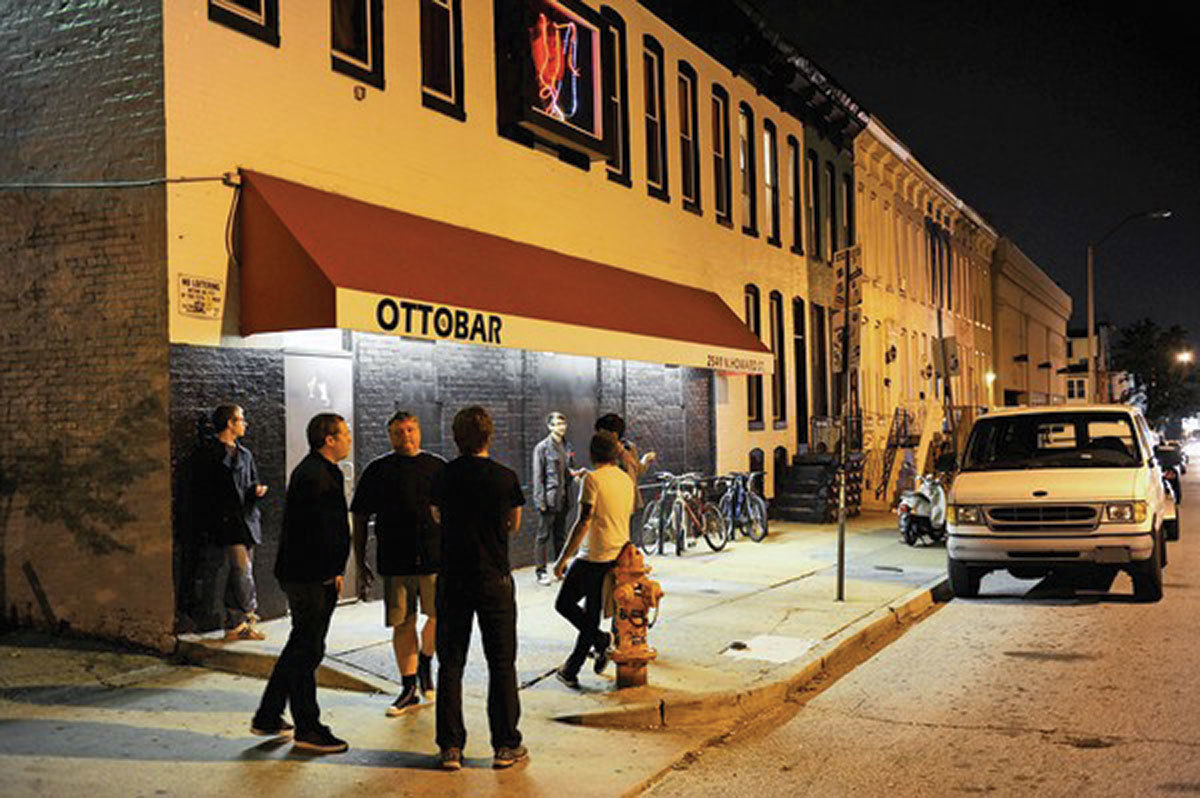

As the city evolves, the Ottobar plays on in Remington.

On his first Tuesday in Baltimore, Sam Herring went to the Ottobar with his bandmates. “Because we were broke,” says the Future Islands frontman. “Because we were broke and you could drink a lot,” adds bassist William Cashion. In 2008, the North Carolina transplants didn’t know anyone in the city, but they knew about the Remington music venue and its infamous Two-For-Tuesday nights. “We were like, we’re going to meet some people,” laughs Herring with mock enthusiasm. “We’re going to meet some babes.” They settled into the L-shaped sofa upstairs, double fisted Natty Bohs, and didn’t make any friends that night. But that wouldn’t be their last time on Howard Street.

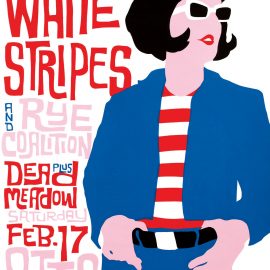

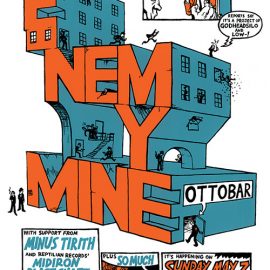

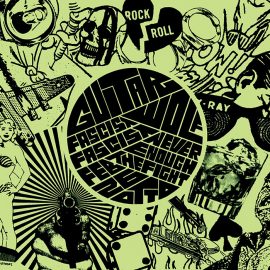

This month, the Ottobar turns 20, and over the past two decades, it has become a stomping ground for artists and musicians, city-dwellers and out-of-towners, who march to their own alternative beat. From its early days downtown to its present digs up north, the local rock club has witnessed thousands of concerts—some performed to empty rooms; others to a crowd packed body-to-body and covered in sweat. It has watched the city and its music scene grow and evolve, managing to stay open—even thrive—as smaller clubs closed down and larger venues opened up. Under those bright lights, audiences rocked out to The White Stripes, swayed to the sounds of Norah Jones, and watched as a few hometown kids turned into international stars.

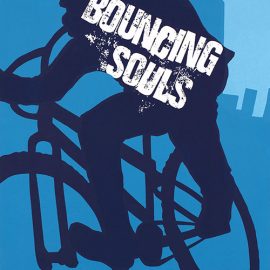

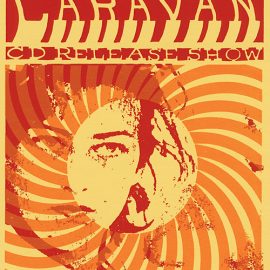

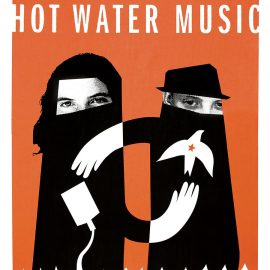

It would be easy to call the Ottobar our 9:30 Club, our Stone Pony, even our CBGB—but none of those clubs have stayed as unapologetic and underdog as their original iteration, if they even still exist. After all these years, the Ottobar remains as decidedly dark and dingy as it ever was, smelling of cigarette smoke, body odor, and last night’s stale booze. Old fliers still cover the walls, sloppy graffiti stays scribbled across the bathroom stalls, and gruff doormen wait at the back door armed with hand stamps that linger like a hangover. And every night of the week, the small black stage still represents the Ottobar’s original M.O.—and the spirit of Baltimore: We’ll take you, any way you come.

“Think about all that’s changed in Baltimore over the last two decades, but the Ottobar’s still there.”

“You never really felt left out at the Ottobar, which is probably one of the reasons it’s been around for so long, because—20 years?” marvels Sam Sessa, former entertainment editor at The Sun and music coordinator at WTMD. “Think about all that’s changed in Baltimore over the last two decades, but the Ottobar’s still there.”

In September 1997, the venue opened its doors on 203 Davis Street in the old Chambers nightclub. At the time, there was no Rams Head Live or Baltimore Soundstage, no Metro Gallery or Sidebar. “There was kind of only one club at any given time,” says Lee Gardner, former music editor at City Paper. “The Ottobar came along and became the cool place to play. It was this professionally run rock club on one hand and this sort of weird, crazy space on the other.”

At the time, two of the town’s most popular venues were the larger, IMP-partnered Fletcher’s in Fells Point and the underground Memory Lane in Pigtown. “When Memory Lane closed, that left a giant hole for something like us to step in,” says Ottobar co-owner Michael Bowen, who was a musician himself as lead singer of the punk-pop goofballs Buttsteak. “Baltimore definitely needed a space that would be a little more adventurous, so when Davis Street opened, we became a natural place for shows without as much red tape.”

Located in the heart of downtown, the Ottobar became a go-to for the city’s rebellious rock scene. From the start, it was open seven nights a week, booking everything from local indie, punk, and rock bands to national touring artists for its 125-person room. “We rarely turned anyone away,” says the venue’s booker and promoter Todd Lesser. “We didn’t have any real limitations. We just were eager from the start. There weren’t many rooms in town for loud, artsy bands—and the musicians needed a place to play.”

But Davis Street wasn’t some audiophile’s Shangri-La. Instead, many refer to it as a “tiny little box,” with a teeny stage and an even teensier upstairs lounge that held little more than a cigarette machine and pool table. “I don’t want to say it was the Wild West,” says Craig Boarman, who started at the venue as a promoter before becoming partner in 2001, “but it was pretty wild.”

The club brimmed with a cast of characters, like Rodney Henry of Dangerously Delicious Pies, who regularly performed with his rabble-rousing Glenmont Popes, and Geoff Danek of Holy Frijoles and Rocket To Venus, who bartended in his underwear. Even Bowen’s cat, the namesake Otto, was a fixture on Davis Street, slinking down late at night from the third-floor apartment where Bowen lived as the staff and musicians shared after-show beers. “If you were lucky,” says Boarman, “you’d see Otto.”

To fill the week, the venue started to develop its now-trademark theme nights and oddity shows. Think Smiths/Morrissey karaoke, championship towel and pillow fighting, and the “Salute to Porn” vintage Playboy swap. Sometimes employees would pull all-nighters and put on 6 a.m. breakfast shows. Other times bands would park out front, plug in an extension chord, and perform a full set in the back of their van. During one talent show, Bowen even tap-danced to Led Zeppelin in a meat bikini.

“God, those days were crazy,” says longtime bar manager Tecla Tesnau. “I don’t know if I should actually repeat a lot of this stuff because it might get us in trouble. There are a lot of moments I’m not proud of but that I don’t think I’d ever trade.”

In the dead cold of winter and high heat of summer, people would pack into the Ottobar like sardines, filling the space with the sort of frenetic energy that only comes with the close quarters of a live show. “It was just gritty and punkish and young,” says Tesnau. “We had no idea what we were doing—we were just putting on music and having a good time. But we started to make it happen.”

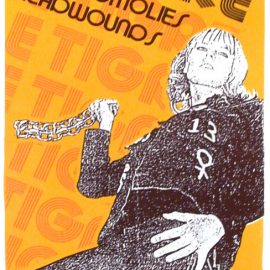

The staff still marvels at some of the bands that played in the early days. Besides the local favorites—Roads To Space Travel, Candy Machine, Lungfish, Oxes, The Oranges Band—they also reeled in soon-to-be national stars: At The Drive-In, Le Tigre, Queens of the Stone Age, My Morning Jacket, Spoon, The White Stripes. “These bands could go to Philly or D.C. and play a bigger venue,” says Boarman, “but they wanted to play the Ottobar.”

By 2000, it became obvious that the Ottobar was in need of a bigger boat, which led to the current digs on 26th and Howard in late 2001. The new spot was still a dive, but now it had space for a few hundred, a dressing room, and a stage that stood a few feet off the floor. “It’s a powder keg—the pit, the blocky stairs, the balcony where people are literally hanging over the sides—everybody’s stacked right on top of each other,” says rocker J. Roddy Walston, who played some of his first beer-soaked shows in Baltimore there and bar-backed on the side. “There’s something about it that feels like the whole place might erupt.”

But not long after the move, the Ottobar was confronted with something new: competition. By the early aughts, Hampden had started its evolution into a hipster haven, and Station North was quickly becoming an edgy enclave as the Wham City arts collective settled into the Copycat building on Guilford Avenue. On either side of the venue, new spaces were slowly opening up. “But that’s when the ideas started coming,” says Boarman.

Rock shows alone were not going to save the Ottobar. Upstairs, they got rid of the old jukebox, expanded theme nights to include the likes of Metal Mondays, Two-For-Tuesdays, and Wednesday karaoke, and put the black-and-white-tile dance floor to good use with a new influx of DJs. “A lot of the old-timers said, ‘Oh, it’s not like the old days,’ and it’s true—it wasn’t,” says Tesnau. “When we moved to Howard Street, we didn’t just want to be a spot for our friends anymore. We wanted to showcase how amazing and diverse the talent is here in Baltimore. That’s how we’ve stayed fresh.”

In fact, while sports games and dance parties did not go down well with the local rock crowd at first, those events—including the “Underground” Brit-pop and New Wave dance nights and the more recent Beyoncé-fueled dance-offs—became some of the venue’s most popular happenings. “You could go to the Ottobar one night for an entire week and you would see seven totally different acts with seven totally different audiences,” says Sessa. “Yes, it’s a ‘rock club,’ but it’s so much more than that.”

“It’s a powder keg,” says J. Roddy Walston. “There’s something about it that feels like the whole place might erupt.”

Even as the neighborhood continues to experience a rapid renaissance, thanks to an infusion of movers-and-shakers such as Lane Harlan, Spike Gjerde, and Seawall Development, the Ottobar staff is excited about their future in Remington. They’ve endured enough change to know that they can make it; they’ve already survived worse.

In 2014, the team was devastated by the stabbing death of employee Tom Malenski, which took place outside of the venue. A couple months later, they were struck by a lawsuit over a broken neck caused by a crowdsurfer three years prior. “A lot of things have happened to them that could have really damaged or destroyed a business,” says Gardner, “but somehow they’ve weathered it.”

Indeed, those hardships have only made the Ottobar stronger. “We’ve definitely been through some rough stuff,” says Tesnau, “but we’ve come through the other side, and that’s because we stick together.”

That familial ethos extends beyond the Ottobar’s payroll, trickling down to the community it’s helped cultivate and an entire generation of Baltimore musicians it’s helped raise. “I’m having a hard time thinking of another venue that we’ve spent more time in,” says Jenn Wasner of Wye Oak. “Growing up in Baltimore, if there was a show coming through town that you wanted to see, chances are it would be at the Ottobar. We’ve certainly had some of our most moving and connected shows in that space, both performing and attending. There’s a lot of history there.”

It’s also the place many of those same bands choose to play when they return from their globetrotting tours. “The thing is, we don’t get nervous playing in front of 3,000 people in Berlin or 15,000 people at a festival,” says Future Islands’ Herring. “We get really nervous in Baltimore. Because those are the people who really know us.”

Sure, the Ottobar can’t stay a rebellious teen forever, and after all these years, it has certainly grown up. But the pit still smells like sweat, and the alley is still studded with cigarette butts, and they’re still booking seven nights a week, including many a hard, head-banging rock band. “You don’t know what’s going to happen until you have the 20/20 perfect vision of retrospect,” says Tesnau, “but even back in the day, we knew it was pretty magical.”

That magic was on full display during the first of Future Islands’ four homecoming shows at the Ottobar this spring. Now arguably Baltimore’s biggest band, they took to the small black stage and, after a quick thank you, launched into a lush new song off of their critically acclaimed fifth album.

“Baltimore has meant so much to us over the last nine years,” said Herring to the sold-out room. “It’s given us great life. It’s given us our loves. It’s really cool to be doing this shit at the Ottobar right now.”

Underneath that shimmering disco ball, he’d go on to sing some 100 songs that weekend, unleashing his shape-shifting dance moves and reaching out into the buoyant crowd that filled the room and hung from the balcony and spilled up and over into the mid-level bar.

Nearly a decade after those fateful beers, they now had rooms full of friends. “Future Islands, Beach House, Dan Deacon—many of them could play The Lyric,” says Sessa, “but they want to play the Ottobar, because it feels like home.”