Education & Family

What It Feels Like

Essays on losing weight, giving birth, and other body-owning experiences.

what it feels like tO

Lose Weight

Julie Hagan tells her story to Jane Marion

Photography by Mike Morgan

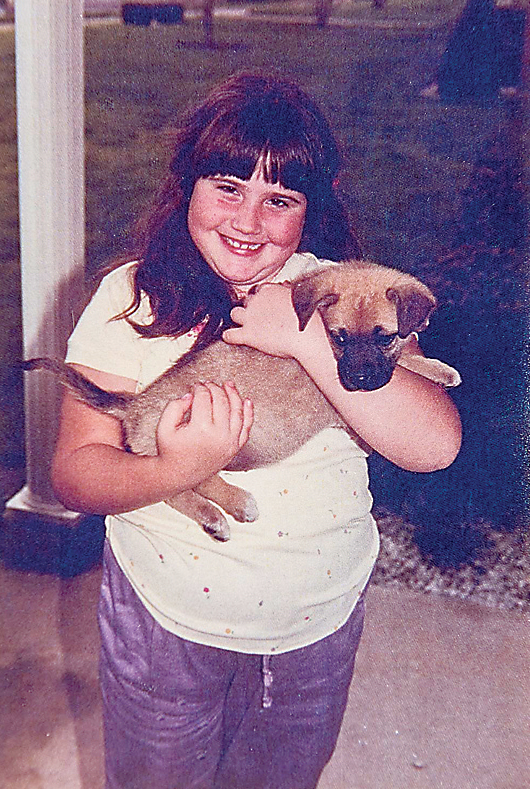

julie hagan as a young girl

Even in kindergarten, Julie Hagan recalls that she was the biggest girl in the class. “I had a weight problem my entire life,” says Hagan, sitting on the sofa in the living room of her Elkridge home next to jug-sized jar of protein powder for shakes. It impacted every aspect of her life, she says, and she learned coping strategies to avoid humiliating situations. “As a kid, it got to the point where I’d go to the doctor’s office and they’d weigh me with my back to the scale so I couldn’t see my weight,” she recalls.

Through the years, Hagan desperately tried every diet. “You name the diet, I tried it,” she says. “Weight Watchers more than you can count,” she says. “It was like, ‘Let’s try eating only salads or fruit or starving yourself.’” She tried to stay active, as well. “I did it all,” she says with a laugh, “from the ThighMaster to Richard Simmons’ Sweatin’ to the Oldies and Deal-A-Meal.”

Seemingly, whatever tactic she tried, Hagan continued to gain weight. By high school, she recalls, “I was wearing a women’s size 24.” Hagan would lose up to 25 pounds from her 5’9” frame, but she’d gain the weight back as soon as she went off her diet. “And I needed to lose 100 pounds,” she says.

Weight impacted every aspect of Hagan's life.

By age 29, Hagan was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, taking seven pills a day to control her disease and other health issues, while still trying to keep her weight in check. In 2009, she went on a radical liquid diet during which she drank nothing but protein shakes four times a day for six months. She lost about 50 pounds, but gained it back within a short period of time after resuming her normal way of eating, despite continuing to work out. “I was 36 years old,” she says, “and my doctor says, ‘I hate to tell you this, but your diabetes is getting worse.’”

For Hagan, the answer, while not a panacea, was surgery. Tired of yo-yo diets that didn’t work and exercise that barely made a dent, Hagan decided to undergo bariatric surgery with a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (a procedure that permanently reduces the size of the stomach and reroutes the small intestines) at Johns Hopkins Bayview. “The date was October 14, 2011,” she says. “I call it the rebirth day.”

“I did it all, from the Thighmaster to richard simmons’ sweatin' to the oldies and deal-a-meal.”

Within a month, Hagan had lost 27 pounds. Within about four months, she had lost another 48, and in less than a year, she had shed nearly 100 pounds. But a part of her still didn’t believe it.

“When you look into the mirror, it just looks like you,” she says. “You’re changing so much that it takes a while for the brain to catch up. This is how I always saw myself, and I thought that this is how people saw me when I was walking around as a nearly 300-pound person, but they didn’t. I feel like I’m finally true Julie—this is how I was supposed to look.”

julie hagan at home admiring her figure

Hagan also learned that doors opened, quite literally, with her newfound frame. “I was walking up to my office one day and a guy ran to get the door for me. I guess if you’re 300 pounds, you’re perfectly capable of opening the door yourself, but if you’re 185 pounds, you’re not.”

Six years later, Hagan has kept the weight off, her diabetes has disappeared, and she’s never felt healthier. (Her success inspired her mother and husband to get bariatric surgery, as well.) “My dragon was a 100-pound dragon and it was ugly and snarly and vicious and wouldn’t go away,” she says. “I was taking pebbles and hitting it. It would back off a bit, but that weight dragon was unbeatable. This was the tool I needed to beat that foe, and it was the best thing I ever did.”

what it feels like to

be short

by Lydia Woolever

Photography by Mike Morgan

The importance of height first came into my consciousness around the time I entered elementary school. My grandmother would stand me and my cousin back-to-back to see which one of us, after the few months since we’d last seen her, had grown taller than the other. Jennifer, always one for theatrics, would shout with glee upon the announcement that she was centimeters my superior. I’d shrug it off and go outside to play.

By middle school, I was actually taller than some of my friends, but I should’ve known then, looking at my mom’s 5'5”, my dad at 5 foot 10, and my grandmother—barely 5 foot herself: Amazonian beauty was never in my cards. Alas, old Polaroid pictures live on as proof that I was indeed at least shoulder-to-shoulder with many of my classmates, and even taller than a sorry few. However, as we hit puberty, they shot skyward and out of the kids’ clothing section, while I stayed closer to the ground, doomed for eternity to fit into “preteen” at exactly five feet. Ever since turning 12, with my childhood doorjamb to prove it, I’ve never grown another inch. Everywhere I went, size suddenly seemed to matter. Big hair. Big-screen TVs. High heels. SUVs. In caveman speak, it all seemed to add up to one thing. Big: good. Small: bad.

Back in my bedroom, I yearned for a taller torso. (Maybe then shirts wouldn’t drown me like full-length dresses.) I pined for longer legs. (Then my jeans wouldn’t always have to be hemmed or awkwardly shoved over my socks). Sleeves swallowed my arms and sports jerseys blanketed my body like potato sacks. Capris are just pants on me.

I dreamed of being the gazelle that graced fashion magazines or landed the best roles in romantic comedies before hopping into a convertible and speeding off into the sunset. Julia Roberts. Geena Davis. I didn’t want to be the short, brunette Gal Friday carrying the suitcase—I wanted to be the star. Besides, how would I ever land a tall, hunky Hercules if he had to constantly look down at me? Surely we’d never see eye to eye.

Self-deprecation and a sense of humor became my mode of self-defense—a poorly veiled attempt to use my height to my advantage. In high school, I would joke that if the cops came to bust our house parties, I could always hide in the kitchen cabinets, because obviously they’d never look there. By college, I subconsciously befriended statuesque girlfriends who all dated Goliaths, and so began the running gag photograph: me, standing beneath their armpits, and them, casually using my head as an armrest.

At some point, those same grown men decided it was fun to pick me up. Not on dates, mind you. Instead, they would squeeze me around the shoulders and literally lift me into the air, my feet dangling helplessly beneath my defenseless, compact frame. I didn’t really get the point of this maneuver, but nonetheless, I’d laugh and squirm before begging them to put me down.

As I grew older, graduated from college, and came into a new (yet same-size) version of me, I learned to muster up the strength to say no before those meatheads even approached me with their wide arms and I’m-a-get-you grins. Instead, I said yes to the fact that I could wear high heels anytime I wanted to, no matter the stature of the man I was dating, and I could wear messy buns on the tippy top of my head and not worry about obstructing anybody’s view. Sure, I still can’t see anything at concerts and my seat almost touches the steering wheel in my car. But, at 29, I can duck through crowds like nobody’s business, and I rarely get whacked in the face by any rogue tree branches. Turns out, I love being small, and even though I know I’ll only shrink more as I get older, I’m okay with it. Because even when I’m 80 and barely perceptible, I’ll subscribe to Shakespeare’s famous line: “Though she be but little, she is fierce.”

Oh, and I found myself a tall, hunky dude of my own after all. He’s nearly a foot higher than me and our hugs are perfect. He calls me “little lady,” and instead of lowering his eyes, he looks up to me—and all of the big things I can do despite my size. Though he did have to buy me a step stool so I can reach the highest shelves.

what it feels like to

give birth

By Megan IseNnock

Photography by Mike Morgan

I can sum up my second pregnancy in four words: I must have forgotten. As I heal from my second C-Section in two years, I’m stunned by how much I must have failed to recall in that short amount of time. I clearly forgot that, during pregnancy, my already tenuous relationship with sleep turns into full-blown insomnia, which I self-medicate with empty carbs and general unpleasantness. I must have let it slip my mind that, due to daily blood draws and injections to combat my fertility issues, I quickly lose my fear of needles (until it’s time for my epidural, in which case my stance on needles reverts to total terror). There’s no way I remembered that, during my third trimester, my stomach stretches out before me, tight as a bass drum, and makes it impossible to do things like wear shoes with laces or walk between cars in a parking lot. I was also extremely surprised to relearn that, as my due date approaches, my navel turns a bruised bluish color then flips to an outie, giving me a freaky humanoid Troll doll belly button. And the memory of what it’s like to voluntarily allow a stranger to temporarily paralyze me so another relative stranger can pull a baby out of an incision in my stomach clearly vanished from my personal history.

It seems I forgot all the little delights of recovery, too. Like the demonic trick the nurses played by removing my catheter hours after surgery to force me out of bed. Or how those same nurses came around every two hours to knead my poor torso like angry bakers. I definitely forgot that I was offered a squirt bottle in lieu of toilet paper, and ibuprofen instead of the intravenous morphine I so clearly deserved. And I simply couldn’t have remembered that, before my first shower after birth, while I was alone and quiet and naked, I’d cried while surveying the damage. The poor woman hunched over in the mirror with her doughy arms and deflated (yet also bloated) stomach and massive incision couldn’t have been me.

six weeks after giving birth to edie.

Because if I’d remembered this—any of this—then surely I wouldn’t have sought out my reproductive endocrinologist to conjure up the science needed to get me pregnant again. No sane person would do this to themselves twice, especially not so very much on purpose.

And yet, 11 months after the birth of my son, I started the process again. Pills, shots, invasive sonograms, weight gain, mood swings—all just to launch myself into the nine-month orbit of reflux, migraines, stretched skin, swollen feet, kicked organs, confounding patches of cellulite, and constant peeing.

But how could I look at my son and not need another? How could I not trade a combined 18 months of discomfort and 16 weeks of surgical recovery for these babies? Our son, Lou, all light and love. And our daughter, Edie, who is still so tiny and new, but feels like she’s been here the whole time. My seven-inch scar isn’t pretty, but it’s how our family got here. I’d hang a portrait of it in a museum if that were in any way appropriate for public consumption.

Now that I’m once again on the other side of the brutal miracle of birth, it already feels nostalgic. As time slowly undoes the damage to my body, I’m left with less tangible evidence of what it went through, and though I’m grateful for the softer memories and smaller waistline, it’s the scar I appreciate most now. My children’s births are written on my body—a beautiful line there to remind me of anything I might forget.

what it feels like to

Get a boob job

By JANE MARION

Illustration by Andrea De Santis

My body and I go way back. Fifty-four years to be exact. It saw me through years of daily ballet practice in my teens. It helped attract my husband of 31 years. It allowed me to scuba dive and practice martial arts for more than a decade. It helped me carry and bear three children.

Despite some wear and tear at this point, as well as the occupational hazards of being a food editor, people have always been quick to compliment me on what my mother, Millie, calls “my figure.” I’m your average non-supermodel—a 5-foot-4 redhead with green eyes and a slightly softened middle, but I look decent enough in a pair of jeans.

But like most people, I had an area of my body I felt self-conscious about. Namely, I always longed for bigger breasts. As a kid, my friends affectionately called me Mahogany, or “Ma” for short, after the then-flat-chested Diana Ross, who was starring in the 1975 movie about a design student who becomes a runway model. (This was plausible, of course, because clothes hang more smoothly without bumps in the road.)

When other girls were starting to develop in their early teens, my collection of undershirts fit just fine. Hitting puberty, I grew taller, and ever so slightly wider, but my chest remained as flat as the tiles on my kitchen floor. I often felt like a stick-figure drawing—only half complete, not quite anatomically correct. Just to give you a sense of how little there was to work with, the first time my then-boyfriend (now husband) and I fumbled in the dark, he thought that his hands had taken a wrong turn as he reached his destination (aka my training bra). “I could have sworn I was feeling your elbow,” he quipped years later. But I knew he wasn’t joking.

By the ’90s, the plastic surgery revolution was on the threshold of going big (so to speak), and enhancement was no longer only the provenance of Hollywood stars. So in 1998, at the age of 34, after giving birth to three kids in four years, I started to consider the possibility that if I couldn’t grow a pair, I would just buy them. At the time, I was living in Orlando, where skin is always in. In retrospect, my longing was likely some form of an early-onset mid-life crisis, the male equivalent of a red convertible, though slightly less expensive. But after three pregnancies, I simply wanted to reclaim my own body.

My husband, an orthopedic surgeon, does not believe in elective surgery and did not encourage me to tamper with my tatas. But on one memorable car ride to tour Cape Canaveral, he was finally feeling worn down. “If it means that much to you,” he said from the behind the wheel of the minivan, “then just do it.”

Once I made the decision, the hardest part was reconciling the notion that fake boobs and my Ivy League degrees did not mix. I definitely had my doubts. My identity was tied into being smart, not sexy. I thought of those traits as mutually exclusive at the time. I was sure that having big boobs was inversely proportional to one’s IQ, and I feared that they’d serve as a shield that might get in the way of people seeing the real me. Furthermore, I did not want to turn back the clock on bra burning (I mean, my sister attended Smith College, Gloria Steinem’s alma mater!), nor did I want to have to wear a bra at all times. Little did I know then, but that’s the beauty of breast augmentation—things tend to stay firmly in place without having to batten down the hatches. In time, vanity won out.

Wisely, I decided to stay small and picked something to fit my frame. (I always joke that I’m not a B-cup or a C-cup, I’m a 320 cc cup, as in cubic centimeters of saline solution.) Even so, in those first few weeks after surgery, seeing hills where there were once valleys was strange and felt very out-of-body. When I leaned over, I’d hear a weird sloshing noise and feel this strange rush of fluid. It felt like two snow globes were shaken, swirled, and stuck under my skin. Why had I done this to myself, I wondered? And yet, the sight of my new silhouette in the mirror quickly replaced that feeling.

Two decades later, these 320 cc’s of saline solution are as much a part of me as any other part of my body. Getting implants hasn’t changed my life in any fundamental way. They haven’t made me any happier or dramatically altered my appearance. Getting implants has not been a resume builder or given me some sort of special superpower. But getting them did complete me in a different way than I’d expected. Getting implants empowered me to realize that this was my choice for my body, which falls under my jurisdiction—and no one else’s.

It was only recently that I shared the news with my daughter, Sophia, because I’d always wavered on whether she needed to know at all. Twenty years ago, before heading to the surgicenter, the last thing I did was kiss the top of her infant head covered in fine red fuzz. At the time, I wondered how I might explain this to her when—and if—that day ever came. If I’m being honest with myself, I didn’t want her to judge me or send her the wrong message. But she turned 21 this month and has just returned from living abroad for three months in India. She saw—and experienced—female oppression firsthand. I reasoned that this was the right time for her to receive the news. Funnily enough, she already knew, though she wouldn’t reveal her sources. “I figured you’d tell me some time, and I guess that time was today,” she said nonchalantly.

I guess you could say it was a teachable moment—for both of us. She taught me that she'd always accepted me for who I was (and could keep a secret). I taught her that she’s lucky enough to live in a place where she’s free to be whomever it is she wants to be—and that the life she leads should be of her own choosing. She gets to decide. This is, in fact, a tenet of feminism, and there’s freedom in believing in that. And trust me, there’s nothing more liberating than being endowed and not actually needing a bra.