Robert Parker, the father of modern wine criticism, ages like fine wine.

Home & Living

The Wizard of Wine

Robert Parker, the father of modern wine criticism, ages like fine wine.

Robert Parker is serving me wine. And when the most famous wine connoisseur in the world hands you a glass of rosé, you take notice—as does he. The blush-colored Prieuré de Montézargues Tavel reveals notes of watermelon and berries, Parker says as he savors a sip, joking, “Now everyone will want to buy this wine.”

That’s how powerful Parker’s word is in the wine world. A nod from him sends acolytes and experts alike scurrying in search of his recommendations. “He has a sixth sense of a palate,” says longtime friend Bob Schindler, owner of Pinehurst Wine Shoppe in North Baltimore. “It put him on the map.”

Parker has come a long way from his meat-and-potato days growing up in Monkton—founding The Wine Advocate magazine, devising a 100-point rating system used around the world, and writing numerous books about wine.

But his life is on the cusp of change as he steps back from 80-hour work weeks that involved tasting more than 10,000 wines annually, just as The Wine Advocate, the industry bible he once helmed at his home, celebrates its 40th year. “It’s time to let the young people move in,” he says.

In his current role, he is no longer writing reviews for the magazine, but is still a minority shareholder and is listed as president on the masthead.

Wine cellar at Magdalena named in Robert Parker's honor. —Urban Row Photography

During this transition, Parker and his wife, Pat, are enjoying spending time in their comfortable, rambling house—Pat’s childhood home—that sits on more than four bucolic acres buffered by Gunpowder Falls State Park and Prettyboy Reservoir in Parkton in northern Baltimore County. They are amiable hosts, pouring wine, offering peach iced tea and artisan chocolates to guests as they shepherd their beloved English bulldogs, Buddy and Betty Jane, in and out of a sunny nook filled with stemmed glassware, whimsical objets d’art, and plants reaching for the ceiling.

They affectionately call each other “Mom” and “Dad” in the way partners do after almost 50 years of marriage. The couple, who are both 71, will celebrate their golden anniversary in July next year. He is dignified, yet casual, in a black sport coat, shirt, and walking shorts on a late spring day, his silver hair shaggy but stylish. She has been compared to actress Natalie Wood in looks. It’s an apt description.

They’ve had quite a lifetime so far, raising a daughter, Maia, whom they adopted from Korea when she was three months old and who is now 31, and traveling the world together. Pat, a former French teacher at Friends School of Baltimore and an avid master gardener and volunteer, says, “We’re in the process of uncomplicating our lives.”

A nod from Robert Parker sends acolytes and experts alike scurrying in search of his wine recommendations.

For starters, the wine expert is reclaiming his family nickname, “Dowell.” “It’s working in a sort of favorable way,” he says. “Robert Parker is the wine critic. Dowell Parker is like an unknown commodity. Going back to Dowell is a nice change.” Dowell originated from his middle name, McDowell. He used the childhood moniker until he attended the University of Maryland School of Law—yes, he was a practicing attorney, passing the bar exam on his first try—when professors called him Robert or Bob in class.

But his formal name will not be forgotten. Two area restaurants have christened rooms after him. Magdalena in The Ivy Hotel in Mt. Vernon has dubbed a private dining room the “Robert M. Parker Wine Cellar.” The elegant white-brick room is lined with 800 bottles of boutique wine, some of which were recommended by Parker, according to Rob Arthur, general manager of the exclusive hotel and restaurant. “We wanted to honor a Baltimore guy,” he says.

Vito Ristorante in Cockeysville is transforming an extra room into a dining area for 50 to 60 people that will bear Parker’s name. The owners, Tony and Vito Petronelli, want to show respect to Parker, a regular patron. Work is expected to be completed by the end of the year. “When Robert Parker is here, people are so impressed to see him,” says Tony Petronelli. “We do feel special. He’s done a lot for wine.”

Parker points out that he pays for his meals and wines at both restaurants. “I don’t profit from it,” he says. “[But] it’s a nice recognition.”

On a recent visit to Parker’s office in a small white house near the main house, he is relaxed, sitting behind a desk cluttered with papers. On the floor is a giant painting of him and Pat, given to him as a gift by a Chinese art-gallery owner who is a fan. There is a companion piece at home, stashed behind containers of wine, which depicts him drinking straight from a wine bottle. He finds the scenario amusing, though out of character, and doesn’t know where to hang these over-the-top portraits.

When asked about his own wine collection, he pauses. He’s lost count and doesn’t keep accurate records, he says, offering, “It’s much bigger than it should be.” Suffice it to say, a dusky cellar in his house is crammed with bottles, including a 27-liter whopper (as big as a carry-on suitcase) of 2003 Sine Qua Non Grenache he had made for when Maia gets married. It’s stored in a box he calls a “little coffin.”

Despite his relative good health, Parker struggles when he gets up from a chair and hobbles to a door. In recent years, he has had a knee replacement and a hip replacement that later needed to be repaired. He recovered from those surgeries. But a failed spinal fusion five years ago left him without the functional use of his left foot. He uses two canes to get around and spends an hour and a half each day doing aqua therapy in a specially designed tank at home.

Even so, he’s not bitter about this unexpected twist of fate. “My whole life has been very fortunate, to marry your teenage sweetheart and to have the career that I’ve had,” he says.

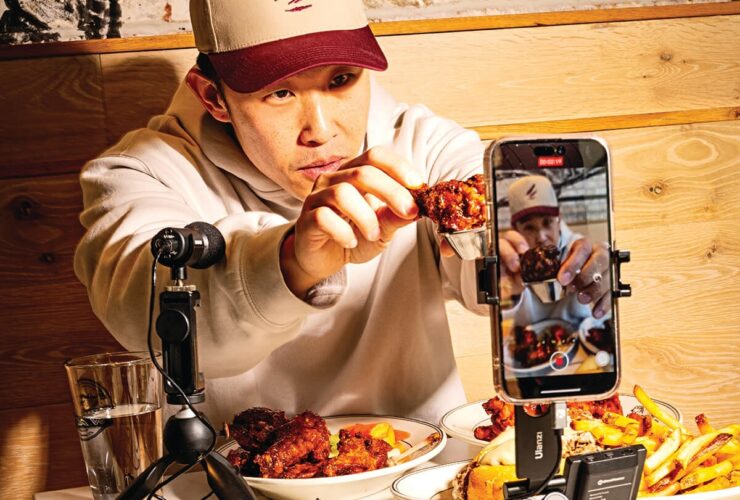

Parker samples wine in his cellar. —Mike Morgan

His goal is to bike the Northern Central Railroad (NCR) Trail that stretches from Cockeysville to the Maryland state line. He was a devoted cyclist at one time and is eyeing a tricked-out adult tricycle to carry him along the scenic path. “It’s drop-dead beautiful,” he says. “I’d like to get back to it.”

His physical limitations also make his self-imposed, partial retirement easier. “I thought it was going to be harder adapting to getting off the road and not tasting thousands and thousands of wines,” he says. “I think, because of the handicap, it’s been easier because you realize you can’t travel like you used to and can’t move at the speeds you’re used to moving at.”

But wine is still a big part of his life. He and Pat enjoy a glass almost every day at home, preferring red wines from southern France. “It’s got an immediate gratification,” he says.

Robert Parker met Pat in seventh grade at Hereford Junior-Senior High School in Parkton. He has her to thank for his discovery of wine. His parents didn’t drink wine. He was a country boy who worked on his grandparents’ dairy farm and was focused on playing soccer and furthering his education.

Then, love came along. By ninth grade, he and Pat were holding hands. By college, they were inseparable, although he went to University of Maryland, College Park, and she attended Hood College in Frederick. When Pat decided to take her junior year abroad in France, Parker visited, and they met in Paris. “From the very first day, she said, ‘You’re going to drink wine,’ and that’s what we did,” he says. “In the course of six weeks, we pretty much had wine every day.”

Not the great Bordeaux, Burgundies, or Champagnes he would later sample, but cheap table wine that whetted his palate for more. “I was fascinated by the beverage because it was unlike anything I’d ever had,” he says. “It gave you a mild sense of euphoria and, at the same time, seemed to work with food, and I always loved to eat.”

He brought his new appreciation of wine back to the University of Maryland, organizing a wine-tasting group for several students. They would pool their resources and buy inexpensive wines, learning about the vintages from books. As the years passed, Parker and Pat continued to go to Europe to sample wines, and he sought out professional wine tastings to develop his palate.

Even before he started The Wine Advocate, he realized he had an exceptional recall and memory for odors, tastes, and textures, “sort of a 3-D grasp of wine when I smelled and tasted it,” he says. He doesn’t see a difference in his palate as he’s aged. “I love wines with personality that say something, whether quietly or boldly,” he says. “The worst thing for a wine is to be indifferent.”

The wine cellar named in Parker's honor at Magdalena. —Urban Row Photography

Parker still has a fondness for food, ordering gourmet ingredients—such as spot prawns from Santa Barbara, California, white truffles from Italy, and black truffles from France—to be delivered to his home, where he likes to grill. He and Pat, who sharpened her cooking skills at LaVarenne in Paris, take a simpler approach to meals these days. “I was an extremely serious cook,” Pat says. “We were big-time entertainers. We were crazy, cooking and entertaining.”

They also appreciate a good meal out. “I really like [chef] Mark Levy at Magdalena,” Parker says. “The guy has genius. He can hit you with some dishes that are flabbergasting in how good they are.”

But he saves his highest accolades for the forces behind the Foreman Wolf restaurant group. “The two people who changed the culinary direction of Baltimore were [chef] Cindy Wolf and Tony Foreman,” he says. “They sort of revolutionized the whole approach to cooking.” The restaurateurs, who operate Charleston and Cinghiale in Harbor East, among other properties, have known Parker since they opened their first restaurant, Savannah, in Fells Point in 1995. “I don’t think you can underestimate Robert Parker’s influence on American wine drinking,” says Foreman, a respected wine director. “I don’t know if there’s one writer in my lifetime who has had that kind of consistency.”

After Parker was awarded the Legion of Honor medal—France’s highest decoration— for his wine writing by former French President Jacques Chirac, he invited Foreman and Wolf to a celebratory lunch. “We were super thankful,” Wolf says.

“I love wines with personality that say something. . . The worst thing for a wine is to be indifferent.”

She also appreciates the attention Parker has given to Charleston, where beef Wellington is a favorite. He has written numerous favorable reviews on robertparker.com over the years and picked the restaurant as having served one of his best dinners of 2016 (along with Magdalena at The Ivy Hotel and Shuko in New York in a three-way tie). “The most highly respected wine writer in the world comes here,” Wolf says. “I’m grateful for the help he has given Baltimore and the help he has given us.” The business partners also note his benevolence. “Bob is extremely generous with his cellar,” Foreman says. “He does so many charity events.”

Bob Dickinson, chairman emeritus of Camillus House, which battles homelessness in southern Florida, recalls a wine dinner he coordinated at Charleston in 2006, when Parker contributed wines from his cellar and picked up the cost of the meal. “It’s not just the money raised,” he says. “It generates more passion. People on the periphery see the possibilities of wine dinners.”

There have been many other benefits since then. A recent Robert Parker wine dinner with a menu of spring lamb and wild salmon was held at Magdalena in May to benefit Camillus House and the Savannah Music Festival. Parker agrees to host the dinners—which can bring in from $55,000 to $117,000— as long as he can split the proceeds with a charity of his choosing.

This sense of helping others explains Parker’s inspiration for starting The Wine Advocate in 1978. He wanted to introduce an independent wine guide for consumers with no advertising. “I was shaped by the Ralph Nader era,” he says. “In law school, we were also shaped by the Watergate era.”

After practicing law for 10 years, Parker left the legal field in 1984 to focus on wine full time. “Everybody thought he was crazy to leave his job,” says his friend Bob Schindler. “Now, he’s the number one wine guy on the planet.”

Law school was also the source of Parker’s well-known point system, which was based on the same scoring structure used to grade classes, from 50 points for the lowest ranking to 100 points for the highest rating. “It caught on everywhere. I’m even amazed at that,” Parker says. “It’s used in Japan. It’s used in Korea. It’s used in France. It’s everywhere.”

He awards points based on factors such as color, appearance, aroma, bouquet, flavor, and balance, rating wines within their peer groups. For instance, if an Oregon pinot noir rates a 90 or above, that means it is an outstanding wine among its type. It’s not being judged against, say, California pinot noirs. According to his system, wines with a numerical range between 60-69 are considered “below average,” meaning they have noticeable deficiencies; those from 50-59 are deemed “unacceptable.”

Parker and his wife, Pat. —Mike Morgan

During Parker’s reviewing days, he would spend three months of every year tasting in vineyards. The remaining months would involve tastings and writing.

But Parker says that “the tasting notes are much more important. That’s really where the verbiage is that describes the wine. The score is the shorthand.”

Parker is working 20 to 25 hours a week now and confers with editor-in-chief Lisa Perrotti-Brown, whose office is in Napa, California. She has known Parker since 2003. When she first met him, she worried that he would have a big ego and be demanding. “I couldn’t have been more wrong,” she says, laughing. “He’s humble and laid-back and is a great person to work with.”

Her mission is to maintain the legacy of The Wine Advocate. “We look to do everything that Robert Parker set out to do with all the integrity and dedication,” she says. “We have no agenda. We have no financial links. We’re completely unbiased.” From The Wine Advocate’s founding until Parker scaled back in 2014, the publication was 100 percent subscriber funded. Now, some of the funding comes from wine-tasting events for subscribers only and from non-wine-connected sponsors including airlines, credit card companies, and luxury cars in addition to subscribers, he says.

Despite his good intentions, Parker has had detractors over the years, people who claim he had too much power, and even death threats in 1990 traced to an irate wine retailer. “That’s part of the territory,” he says. “I was the most influential wine critic for a long period of time. . . . It created a segment that naturally wanted to hate me.”

But will there be another Robert Parker? Tony Foreman doesn’t think so. “We’re in a different place. Wine journalism has changed,” he says. “I don’t think the role exists anymore.” Perrotti-Brown agrees. “Bob was the first person to do this. He’s the father of modern wine criticism,” she says. “There’s never going to be one view so powerful and globally significant.” Parker came on the scene before the internet. Now, free wine blogs are in abundance, so that no one person is capable of rising above the others, he says. “Millennials started this sort of [negative] reaction to experts,” he continues. “It’s the mob that rules—that’s all part of the younger generation.”

At home, Pat Parker reflects on the couple’s early days when “we had no money . . . and, at first, knocked on doors together.” She spent 35 years as The Wine Advocate’s copy editor in the cottage industry that blossomed steps away from their living room. “You can’t talk about Bob without talking about Pat,” says Dickinson of Camillus House. “They’re joined at the hip.”

Pat, whom Parker calls his “daffodil princess,” enjoys showing visitors around their lush gardens, complete with a pond with flashy koi and goldfish, and a chicken coop. She gave her husband hens for his 70th birthday. “He watches them from the house,” she says, smiling.

Their journey together is continuing in different ways. This year, they went on their first cruise, traveling through Alaska. They’re contemplating an anniversary trip, maybe to Paris, where it all began. “It’s been a wonderful ride,” Pat says. “Who ever knew he would become a world-wide phenomenon? It has been incredible.”