History & Politics

Know Them By Their Fruits

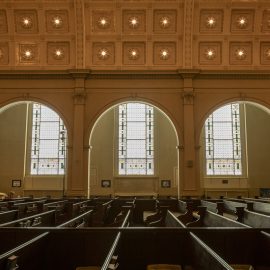

The beautiful First Unitarian Church in Mt. Vernon opened 200 years ago this month.

The early members of the First Unitarian Church in Baltimore were heretics by the standards of local, established Christian congregations. They were also movers and shakers. They founded the church in February 1817, chose an architect in March, picked a site on the outskirts of town, in an area then called Howard’s Woods, in May, and had the cornerstone in place that June. Sixteen months later—200 years ago this month—they opened the doors to the first Unitarian church built in the U.S., the beautiful 17,000-sqaure-foot example of French Romantic Classicism that still stands on the corner of North Charles and Franklin streets today.

The church is significant in the history of American religion, serving as the site of what became known as William Ellery Channing’s “Baltimore Sermon” of May 5, 1819, which laid the foundation for the Unitarian denomination. It is also significant to the spiritual and cultural development of Baltimore, church historian Catherine Evans notes during a recent tour, highlighting early members who created much of the marvelous architecture of Mt. Vernon that grew up around the church.

Congregants George Peabody and Enoch Pratt, respectively, founded the nearby Peabody Institute and one of the nation’s first free public libraries—“for all, rich and poor without distinction of race or color,” in Pratt’s memorable words—around the corner. Rembrandt Peale, one of the church founders, brought the first gas streetlights to Baltimore (and the country), and made the church the first public building in the city with gas lighting, inspiring gawking crowds. The bricks from the Mulberry Street rowhouses that were torn down to make way for Pratt’s cathedral of learning? They were repurposed to build the parish hall, where services are still held each summer Sunday.

Pratt also bought the church its renowned Niemann organ in 1893, a massive 1,500-piece instrument that was restored last year. The church’s seven not-to-be-missed Tiffany stained-glass windows arrived during a major renovation several years later.

“The building, a pilgrimage site for Unitarians, is a precious jewel,” says Rev. David Carl Olson, the lead minister at First Unitarian. “Not just for us, but for the country.”

Despite its independent streak and outsider beginnings, or possibly because of those qualities, Unitarians count four early U.S. presidents among their ranks, including John and John Quincy Adams. Thomas Jefferson never formally joined, but espoused religious beliefs very much aligned with Unitarianism and even predicted the whole country would eventually become Unitarians. (That’s been a disappointment,” says Clare Milton, the church’s 100-year-old assistant treasurer, with a wry smile and a laugh.)

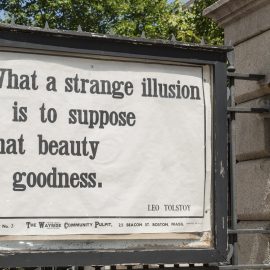

The contentiousness around the upstart Unitarians arose from their rejection of the Trinitarian God (three entities as one being: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) of conventional Christian theology—and rejection of doctrine in general. The Unitarian movement, which influenced the New England Transcendentalism of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, has always embraced an open-minded approach to religious seeking, as well as an appreciation for the natural world and a radical commitment to social justice, starting with the abolition and women’s suffrage movements.

In 2007, First Unitarian hung a giant banner from its façade, declaring “Civil Marriage is a Civil Right” in LGBTQ rainbow colors.

Currently, an equally bold Black Lives Matter flag flies alongside a banner commemorating the church’s bicentennial.

Enoch Pratt, a lifelong Unitarian, says Evans, would have said, “Right on.”

The First Unitarian Church will celebrate the 200th anniversary of the dedication of the church Oct. 28 with an illustrated lecture, “Enlightenment & Architecture,” by Dell Upton, distinguished professor of architectural history at UCLA. The 3 p.m. event and reception afterward is free and open to the public.