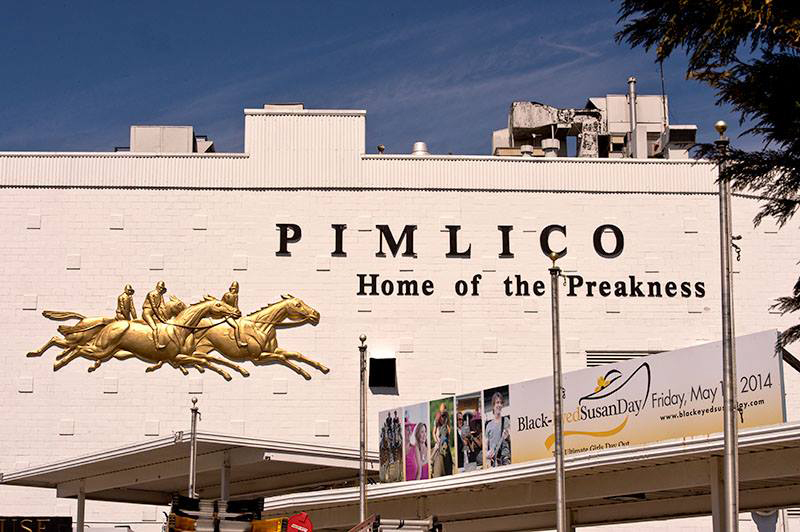

A Maryland Stadium Authority (MSA) study has recommended tearing down the dilapidated Pimlico Race Course and starting over—at a cost of more than $400 million. But while the operators of the track agree in principle with the report’s findings, they’re not up for paying the tab themselves.

The study, released today, envisions multiple, year-round uses for the facility, but focused in the short term on just replacing the clubhouse, grandstands, tracks, infield, and assorted racing-related outbuildings. Retail, residential, units—even a hotel—could be later phases on the sprawling track between Mt. Washington and Pimlico but would likely have to be funded by private enterprise.

According to the study’s findings, without a large investment in the track, Pimlico faces “significant challenges, which, if not addressed, may threaten its continued existence and the success of the Preakness Stakes.”

The study also suggests city and state officials, the track operators—the Maryland Jockey Club (MJC) and The Stronach Group of Canada, which owns Pimlico and Laurel Park—begin talks about the next steps, a recommendation supported by Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh.

“What we believe is, this is a path forward for the Preakness in Baltimore,” Pugh said. “We know this is going to require public-private partnerships, including the state.”

In a statement, Belinda Stronach, chairman and president of The Stronach Group, thanked the MSA for its “thorough and extensive job of understanding and responding to the challenges of the aging Pimlico Race Course. The final conclusions of the MSA report are in line with our assessment that, in order to bring the facility up to par, it will require several hundreds of millions of dollars.”

But the Stronach Group has consistently balked at the idea of paying for such a rebuild out of pocket, saying significant public investment is necessary. The company has suggested it’s open to discussing a public-private partnership.

Marty Azola, president of the Azola Companies, known for historic restorations across Baltimore and a national expert on adaptive reuse, served as vice president for facilities at Pimlico for several years in the late 1990s, and knows every worn-out corner of the property. While he has mixed feelings about dropping large sums on Pimlico, he acknowledges how important it is to keep the race in Charm City.

“The argument about where to run Preakness is not just about the facilities,” says Azola, who’s also author of the recent book Rebuilding Baltimore. “It’s about civic pride. It’s about our nation’s history in Baltimore. We have so few nationally prominent businesses and events in our city. Let’s not even consider losing Preakness.”

But he thinks a less ambitious redo might make more sense.

“I am very aware of the business realities for the MJC and support public financing of the Pimlico rebuild so the MJC can profit reasonably,” he said. “But you could also argue that record crowds keep coming notwithstanding the condition. It’s the event that draws them. I’d recommend a smaller year-round facility at Pimlico similar with state-of-the-art simulcasting, food service, banquet and other revenue-producing spaces. Then provide fair-weather grandstand facilities and all the infield amenities for the extra 100,000 fans that come on that one special day—Preakness.”

Preakness for the owners of Pimlico is like black Friday at the mall—that’s historically the day they show a profit for the year. It’s also the single biggest event of the year in terms of revenue for Baltimore.

“A revamped Pimlico would help support adjacent development indirectly but understand that racing fans are unlikely to venture off site for any meaningful amount of business,” adds Azola.” “It’s the same dynamic as casinos. You need all amenities on-site.”