Health & Wellness

Back to the Future

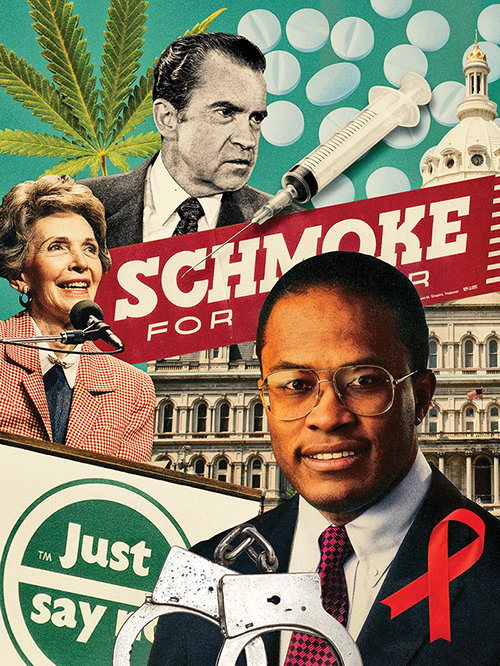

Kurt Schmoke was vilified for wanting to end the drug war. Today, his ideas are becoming reality.

Kurt Schmoke tore up the speech that had been written for him. It was April of 1988, and just months before, the 38-year-old former City College quarterback and Yale-, Oxford-, and Harvard-educated lawyer had become the first elected black mayor of Baltimore. The next morning he was scheduled to address a joint gathering of big-city mayors and police chiefs at the U.S. Conference of Mayors in Washington, D.C. Organizers had asked him to comment on the impact of the War on Drugs on cities and to focus on Baltimore.

“I had two speech writers, and Howard Lavine wrote a pretty good overview of the city and some of the issues we were facing related to substance abuse,” recalls Schmoke today. “But I thought, ‘No, this is a unique opportunity with the police chiefs and mayors in the same room.’ I had one night to rewrite it, and I didn’t show it to anyone, including my chief of staff, because I did not want to be talked out of it.” Only Schmoke’s secretary, who typed it up before he left for D.C., saw the speech.

By the time Schmoke returned to City Hall that afternoon, his political future was an open question.

“I walked through the door, and the first thing I heard from my staff was, ‘What did you say?’” says Schmoke, now the president of the University of Baltimore. “The Associated Press was already working on a story about the speech, saying I was in favoring of legalizing drugs.”

The first draft of history does not always get the facts straight. Schmoke had not proposed legalization. He suggested, in what would become a landmark address, the U.S. ought to seriously consider and debate an alternative approach to the War on Drugs. He also used the term decriminalization, not legalization. Schmoke had been thinking about national drug-control policies and the historical similarities to Prohibition—“the war on alcohol,” in his words—for some time. The issue had become more urgent and personal for Schmoke when an undercover detective was shot and killed during a drug buy three years earlier while he was the city’s state’s attorney.

“Marty Ward,” Schmoke says, the name of the fallen officer and circumstances still fresh three decades later. “He was married and a father. He was wearing a body wire, and I had to listen to the recording several times, because if there was intent to [knowingly] kill a police officer, then the death penalty would come into play. You could hear everything that happened.”

Schmoke had also begun reading critiques of the drug war by then-Princeton professor Ethan Nadelmann, who advocated a European-style, harm-reduction approach to drug use. “How could we improve communities without a war on drugs?” Schmoke says. “We didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. Law enforcement would make a show of the drugs and money they seized, but the problem persisted. Marty Ward and all that was floating around in my head before the mayors’ meeting in D.C. This group will be engaged, I thought. Hopefully, it will start a discussion.” How was the speech received in the room?

“Deafening silence.”

Eventually, a single police chief from Minneapolis weighed in. Anthony Bouza had begun his career in New York City, previously serving as police commander of the Bronx. He had witnessed the collateral damage of the early modern drug war firsthand. Initially launched with federal policies by Richard Nixon in 1971, the drug war was dramatically ratcheted up on the state level two years later, when New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller enacted a series of draconian statutes. Known as the Rockefeller Drug Laws, they included mandatory minimum sentences of 15 years to life for possession or sale of some drugs and sent drug arrests skyrocketing. They made, however, no discernable impact on crime. In fact, crime and homicides spiked along with the state prison population, which soared by 500 percent in the ensuing decades. Schmoke had recognized similar scenarios disproportionately impacting minority communities playing out in Baltimore and across the country. In Maryland, the state prison population more than tripled from 1980 to 2000.

“Kurt Schmoke was a very impressive young mayor,” says Bouza, the author of several books on law enforcement. “All of us sitting there participated in the War on Drugs, and we all lost. Nobody else would admit it.”

The quiet national policy discussion Schmoke hoped to inspire among elected officials and law enforcement leaders did not quite unfold the way he imagined. The response that ensued was more like national outrage, particularly after his testimony that September in front of the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control.

Rather than compelling him to retreat from his call for debate, the intervening months had only reaffirmed his belief that the drug war was unwinnable and counterproductive. Since the anti-narcotics Harrison Act of 1914, Schmoke told the House committee, the U.S. had been conspicuously ignoring the reality that drug prohibition increased crime and did not prevent addiction. He was now openly advocating for the decriminalization of marijuana and a public-health and treatment approach to addiction regarding harder drugs.

“We have spent nearly 75 years and untold billions of dollars trying to square the circle, and inevitably we have failed,” Schmoke said. Later, he would refer to the drug war as “our domestic Vietnam.”

New York City Mayor Ed Koch, according to The New York Times, responded by telling the panel that Schmoke was “a brilliant spokesman for a bad idea.”

Controversial television appearances soon followed—on Nightline with Ted Koppel, where Congressman Charles Rangel, chair of the House select committee, blasted Schmoke and the idea of decriminalization; with Morley Safer on CBS; on The Phil Donahue Show; on PBS, and elsewhere—as well as countless print and radio interviews and speaking engagements. Schmoke was in such demand that he turned down Oprah when her producers called; he was worried constituents might think he was neglecting his day job. (“Dumb move,” he jokes.)

First Lady Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign was cresting, and the backlash was so reflexive that Schmoke began introducing himself at public speaking events as “the young man people say used to have a political future.” Forgotten by many critics was that he had campaigned for City State’s Attorney in 1982 as a dedicated drug warrior and had overseen the prosecution of thousands of drug offenses. “Like everyone else in 1982, I thought that you could arrest your way out of it—cut off the distribution,” But his experience and evolution on the issue did not seem to carry weight. Instead, political opponents and the media treated him as a pariah, and public opinion kept tilting further in the other direction. By the fall of 1989, one year after Schmoke’s Capitol Hill testimony, 64 percent of Americans in a Times/CBS poll cited drugs as the nation’s most important problem—at the time the highest number ever recorded for a single issue in the poll. Seven in 10 also approved of new President George H.W. Bush’s plan, which he had presented in his first prime-time television address, calling for a major increase in local law enforcement action, stiffer penalties for first-time drug offenses, and more federal prisons for drug offenders.

Meanwhile, Schmoke kept at his lonely battle, addressing public forums in Baltimore and elsewhere. He’d start by asking the same questions: Do you think we are winning the War on Drugs? Do you think more of the same will make a difference? And if not, are you willing to consider something else? “Kurt Schmoke was brave. You have to remember this was also on the heels of [former Maryland basketball star] Len Bias’ death. Drug use and decriminalization was a third-rail issue,” says Kevin Zeese, who served as executive director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) from 1983-1986. “But look at where Portugal, which had a huge heroin problem, is today. They passed decriminalization in 2001 and have seen a 75 percent drop in drug cases.” Drug-induced death rates and HIV infections have fallen dramatically as well. “And look at Baltimore, where prohibition continues to make life more dangerous, and look at the Gun Trace Task Force case—prohibition breeds corruption, too.”

In some ways, the colossal tragedy of AIDS, profoundly felt in Baltimore, would prove a turning point. Schmoke began talking about the drug epidemic as a three-headed monster—crime, addiction, and AIDS—two of which were clearly public-health, not law-enforcement issues. In 1994, after three years of trying, he finally won approval for a needle-exchange program from the state legislature.

Today, two-thirds of Americans favor treatment over incarceration for the use of hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine, and recreational marijuana is legal in nine states and the District of Columbia. Medical marijuana—not on the radar in the late ’80s and early ’90s—is available in 29 states. Baltimore’s current health commissioner, Leana Wen, has called Schmoke an inspiration as she pushes for treatment on demand and open access for residents and first responders alike to naxolone, a nasal spray medication that reverses the effects of overdoses.

Sitting in a conference room outside his office, Schmoke, dressed in a tie and cardigan, evokes a grandfatherly image. He does not express frustration that the country has taken so long to come around to his once-renegade ideas. He says he is pleased to see progress. He also cautions that, given current U.S. Attorney General Jeff Session’s hardline positions, the drug war is hardly over. It is interesting, too, that reports of Schmoke’s political demise proved greatly exaggerated. “As his campaign manager, was I concerned about the speech he had made and the repercussions?” asks University of Maryland law professor Larry Gibson. “That would be an understatement. But I think people in Baltimore knew he was earnestly seeking solutions. It may have been what he was known for nationally, but it also wasn’t the only issue he faced as mayor. Over time, he began to win people over.”

Schmoke won the Democratic primary in 1991 by a wider margin than he had defeated incumbent Du Burns four years earlier. He also easily won reelection in 1995 and would’ve been favored if he had run for a fourth term.

“By ’95, at [mayoral] forums with other candidates, people would stand up and say, ‘We know where Schmoke is on the drug issue. Tell us where you are.’ And my opponents gave the same old line,” Schmoke recalls. “My opponent would be more on defense than I was.”

Schmoke decided not to run for a fourth term in 1999, in part because he felt like he didn’t have anything new to offer in terms of the city’s escalating deadly violence, which continued to produce more than 300 murders a year. By then, crack cocaine and new gangs had blown apart the city’s older and comparatively stable heroin and marijuana operations in East and West Baltimore. “I thought we were still making progress in some areas, but Baltimore was still a tale of two cities,” he says.

He briefly toured the state and considered a run for governor in 1994, but his heart wasn’t in it. The job he really wanted after leaving City Hall was in the U.S. Senate. But when Paul Sarbanes decided to run for one more term, he looked elsewhere. By the time Sarbanes stepped down in 2006, Schmoke was dean of the Howard Law School—“a job I absolutely loved.”

Schmoke still refers to himself as a “recovering politician,” and he laughs when he looks back at a visit at the White House—for another U.S. Conference of Mayors meeting—shortly after Bill Clinton was elected. In the 1992 presidential race, the drug war, which had strong bi-partisan support, was not a debate topic. Nonetheless, Schmoke was not about to waste another opportunity in front of a potentially important audience.

“I asked President Clinton if he realized the conference was sponsored by a tobacco company,” Schmoke recalls, displaying an oh-so-slight subversive joy in the memory. “Rich Daley [then mayor of Chicago], who had organized the meeting, shot missiles at me with his eyes. Then I asked the president, ‘If I had a green leafy substance in each hand and I told you one of them for certain would kill 400,000 people this year and the other would produce no known deaths, which would you criminalize?’

“He didn’t respond. He just smiled.” When Schmoke came into office in 1987, he wanted to be known as the mayor of The City That Reads. It was his slogan. He wanted to improve the city’s schools, public libraries, and community college.

“I didn’t plan for my name to become associated with decriminalization,” he says. “It just happened. But if that is my legacy, that doesn’t upset me at all.”