Adam Lindquist, director of the Waterfront Partnership’s Healthy Harbor Initiative, cautioned that one year’s data is not enough to make a trend. Still, he could not help but smile over the apparently dramatic progress—documented in today’s annual report of the Baltimore Harbor—the city appears to making in cleaning up its most treasured asset.

At the beginning of the decade, the nonprofit Waterfront Partnership set a goal of making the harbor swimmable and fishable by 2020. At the time, it seemed an impossible task—a literal pipe dream given the state of the city’s century-old underground sewage system.

“[Waterfront board member] Michael Hankin said he’s planning to jump in right outside here,” Lindquist said after the release of 2018 report in Fells Point this morning. “We may need to find a bigger location for a public swim if things keep heading in this direction.

“There is phenomenal improvement,” Lindquist added. “Thirty-two out of 49 monitoring stations showed improvement, including every stream. There are parts of the Jones Falls [a key Inner Harbor feeder stream] that previously received a ‘0,’ in terms of meeting fecal bacteria standards for safe swimming, that met those standards 100 percent of the time in 2017.”

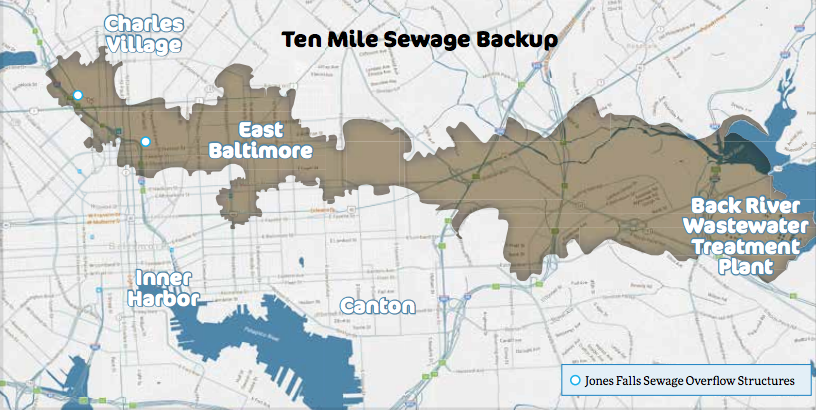

Lindquist and state officials on hand pointed to the start of a new $430 million infrastructure effort that will eventually reduce sewer overflows by 80 percent—the target for completion is 2020—as well numerous volunteer-intensive restoration projects around Baltimore’s harbor and streams. The target of the $430 million Back River Waste Water Treatment project is a 10-mile backup of raw sewage, first reported in 2015, from Charles Village to the city’s treatment facility in eastern Baltimore County.

State delegate Brooke Lierman, a leading environmental advocate in Annapolis, praised local volunteer efforts—which include the restoration of the Gwynn Falls and Harlem Park bio-retention and asphalt removal projects—with a quote from The Lorax, the environmentally conscious Dr. Seuss character: “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

She also touted the city’s recent ban on polystyrene foam, an effort, which she noted was led by city high school students and the youth group Baltimore Beyond Plastic.

Rudy Chow, director of the Baltimore Department of Public Works, said the city has been making significant progress in terms of repairs to the city’s storm water and sewage systems. Last year, the city finalized a renegotiation of an EPA consent decree order to overhaul its antiquated water sanitation infrastructure. “It was pushed off for decades, way too long,” said Chow, who has served as director since 2014. “It’s the prime reason water bills are now going up.”

The overhaul is projected to cost $2 billion when completed in 2031, but Phase I of the effort, repairing and relining the storm water pipes, is underway and expected to be done by 2021. Additional hydraulic improvements are planned after that. According to this year’s harbor water quality report, the number of city-resolved pollution investigations has doubled over the past three years. The 2016 Waterfront Partnership report gave the harbor’s today waters an “F” grade and streams a “D-.” This year’s report did not include grades as in the past, but instead offered more nuanced information.

Chow also pointed to the discovery and removal last year of an estimated 140-ton mass of congealed fat, oil, and trash under midtown—dubbed the “fatberg”—which was causing sewer overflows in the area, as a step in the direction. Education efforts have begun to inform local restaurants and other businesses about prevention

The top five takeaways from Harbor Heartbeat Report, from the Waterfront Partnership release:

1. Fecal bacteria levels in Baltimore’s streams and harbor, monitored by Blue Water Baltimore, substantially improved in 2017. Sewer repairs in the City and County are ongoing and there has been a 20 percent reduction in the number of reported sewer overflows since 2015.

2. Although data shows improved bacteria scores, Waterfront Partnership cannot state what specific actions caused these improvements. More years of data are needed to determine if changes are part of a larger trend.

3. Less trash—150 tons less—was collected from the Harbor in 2017, compared in 2016, which advocates attribute to less rainfall as well as the City’s decision to provide trash cans to all residents and increase street sweeping.

4. Conductivity in the streams continues to be the worst performing indicator with a score of eight percent. Salts and other pollutants are carried into our streams when it rains, raising the conductivity to unsafe levels for fish and other wildlife.

5. Over the last four years, Baltimore City DPW found and repaired 279 pollution sources in the city’s sewer and storm pipes and more than doubled its capacity to perform pollution investigations.

*The third annual Baltimore Floatilla, a fundraiser for the Waterfront Partnership’s Healthy Harbor Initiative, is slated for June 9 at Canton Waterfront Park.