News & Community

Can H-Town Kick Its Habit?

The worst drug epidemic in U.S. history could be a fatal blow to Hagerstown (and other small towns like it).

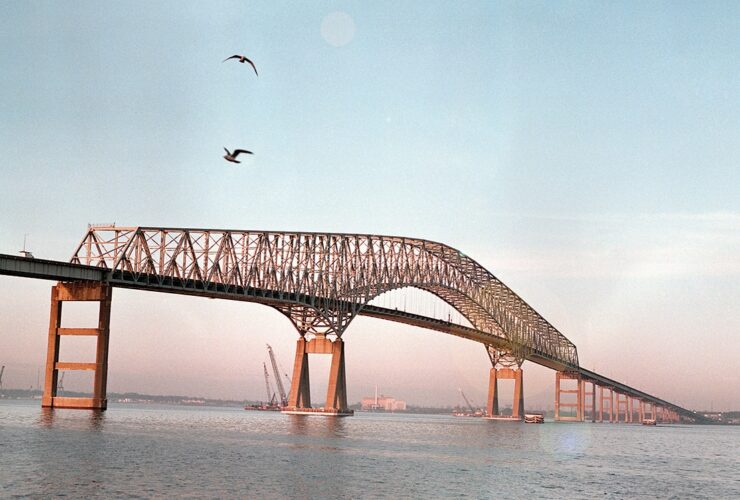

seventy-five miles

west of Baltimore,

the sun has yet to rise over South Mountain, but already a line of cars is arriving at the Phoenix Health Center in Hagerstown. Saturday mornings are the busiest days of the week because the drug treatment clinic is closed on Sundays—meaning that several hundred people begin showing up at 5 a.m. to ensure that they can collect their extra day’s supply of methadone or buprenorphine.

The substance abuse treatment center sits across the street from an abandoned hospital parking garage (the hospital moved out of downtown like nearly everything else), and a seemingly endless stream of addicts in late-model cars, minivans, and pickup trucks come and go until the pharmacy closes at noon. A local taxi company sporadically drops people off. Others walk from nearby apartments. Some folks—a waitress with an apron tied around her waist, a guy in construction gear—are clearly stopping by on their way to a job. Others arrive in pajamas and sweatpants, barely awake, clutching telltale lockboxes for take-home doses. A handful, with newer haircuts and cars, might be professionals somewhere in this politically conservative county. For the lion’s share, however—a nearly all-white mix of solitary adults, young and middle-aged couples, teenagers, and parents dragging along children—it looks like life has been a struggle for a while. Maybe longer. There’s an unmistakable world-weariness written into their faces. Most aren’t even here to get clean but to get by.

Washington street leading east at the hagerstown public square in 1957.

Perhaps as many as three-quarters of those in local methadone programs, according to recovering addicts interviewed for this story, still get high, using coke, crack, ecstasy, Spice, or benzos like Xanax, which are particularly dangerous in combination with methadone. Others sell or trade their methadone or bupe (opioid medications used to suppress withdrawal symptoms) to buy the real thing, faking drug tests to game the system. “Maybe 10-15 percent don’t give you any problem and are trying to do the right thing,” says Lee Green, an addictions counselor who is also an active member of a 12-step program. “That’s how strong the grip of this addiction is.”

When a methadone clinic was first proposed at this site, two blocks from Hagerstown’s “main street,” in the spring of 2001, it was met with vehement opposition. For the past 44 years, since Valley Mall was built on the outskirts of town, shuttering the department stores, retail shops, restaurants, theaters, and five and dimes, there have been hopes of reviving Hagerstown’s once-thriving city center. A methadone clinic was not a part of that vision. The mayor and City Council at the time didn’t want it. Neither did the Washington County health officer or then-Hagerstown Police Chief Arthur Smith, who questioned the wisdom of opening a methadone clinic in a city that, he claimed, did not have a heroin problem. It’s true that from the outside, the county seat of some 40,000 people still looks a bit like Mayberry, with its turn-of-the-century architecture, elegant City Park, church spires, tidy sidewalks, and walkable streets. The huge A&W Johnston clock, first built in 1836 and later refurbished, still stands four stories above the town square in a period brick building.

But the sad fact is that in 2018, Phoenix Health Center draws more people downtown than anything else on a Saturday. Two additional private methadone treatment centers have since opened in the area, not to mention the Washington County Health Department’s outpatient addiction program, which treated more than 11,000 patients between 2013 and its closing this spring due to state budget cuts.

It’s nearly impossible to find a family, including those among the Hagerstown Police Department and City Council, that has not been affected by the town’s still-escalating opioid epidemic. Kevin Simmers, a retired Hagerstown police officer, lost his 19-year-old daughter to an overdose and is now building a women’s recovery center, Brooke’s House. Thirty-two-year-old City Councilwoman Emily Keller, a go-getter single mom and insurance agent, lost her oldest friend to an overdose and ran for office specifically to lead the fight against the opioid epidemic. “There wasn’t a door that I knocked on when I was campaigning for City Council that people didn’t say heroin and the opioid crisis was the number one issue,” Keller says. “Everyone had a story.”

“Now it’s everywhere. It’s a phone call away.

They’ll deliver. Quicker than ordering a pizza.”

n its heyday, Hagerstown built the massive Fairchild transport planes that carried U.S. troops across the Pacific during the Korean War; post-war, they made Boeing jets. Hagerstown built automobiles, bottled Coca-Cola, made shoes, clothing, furniture, and Breyer’s ice cream, and was the world’s largest manufacturer of pipe organs. But today, while Frederick, just 25 miles east down I-70, is regularly named among the best places to live in the U.S., Hagerstown more closely resembles a microcosm of Baltimore—essentially a small town with big-city problems, continually in survival mode. In truth, Hagerstown has a higher poverty rate than Baltimore City, a higher percentage of people under 65 with a disability, lower home-ownership rates, and a lower percentage of its workforce with college degrees. (It also broke a record last year with eight homicides, sending its per capita murder rate past Philadelphia and Chicago.)

n its heyday, Hagerstown built the massive Fairchild transport planes that carried U.S. troops across the Pacific during the Korean War; post-war, they made Boeing jets. Hagerstown built automobiles, bottled Coca-Cola, made shoes, clothing, furniture, and Breyer’s ice cream, and was the world’s largest manufacturer of pipe organs. But today, while Frederick, just 25 miles east down I-70, is regularly named among the best places to live in the U.S., Hagerstown more closely resembles a microcosm of Baltimore—essentially a small town with big-city problems, continually in survival mode. In truth, Hagerstown has a higher poverty rate than Baltimore City, a higher percentage of people under 65 with a disability, lower home-ownership rates, and a lower percentage of its workforce with college degrees. (It also broke a record last year with eight homicides, sending its per capita murder rate past Philadelphia and Chicago.)

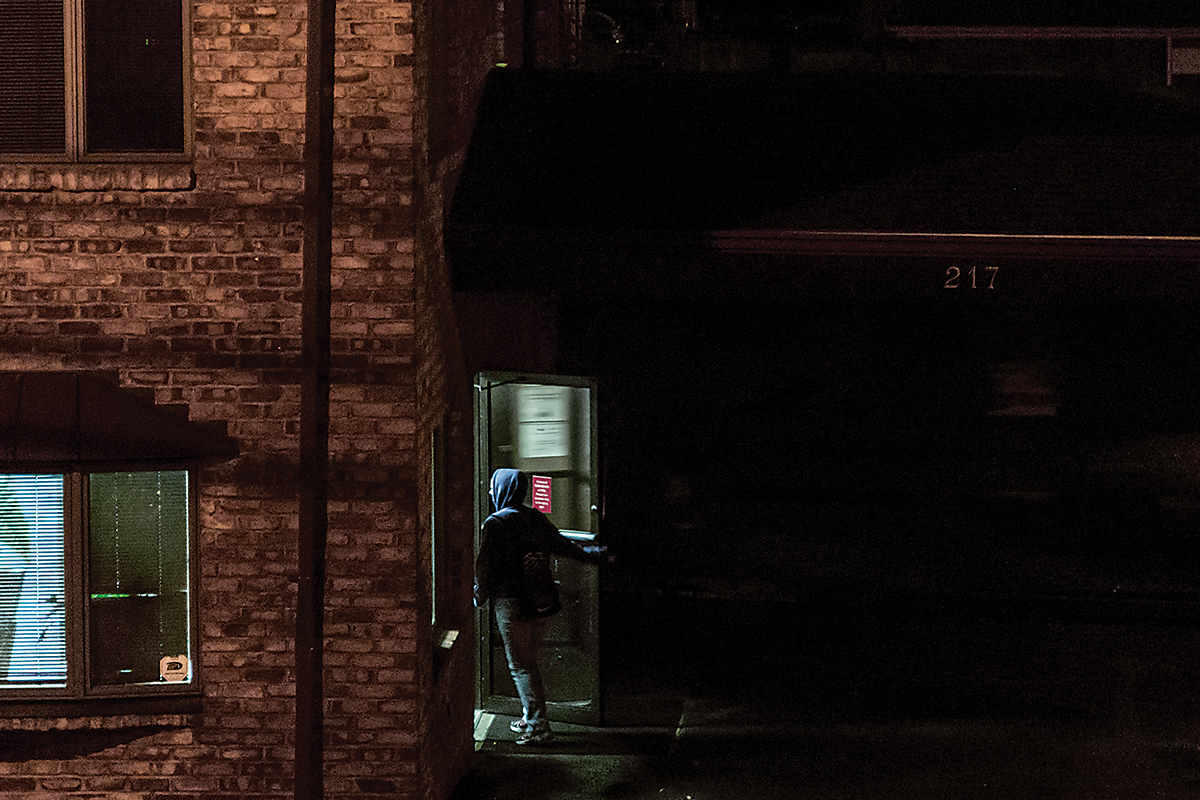

A Pedestrian on north Prospect Street.

Opioids may be the deadliest catastrophe to hit Hagerstown, but the current crisis follows a long string of blows to a city that never made the transition from a mechanical to a hi-tech economy. While the most pressing question confronting Hagerstown—and other resource-deprived towns in Maryland such as Frostburg, Cumberland, Cambridge, Snow Hill, Elkton, and Edgewood—may be how to get immediate help to those struggling with addiction, the broader question is more vexing: How does an isolated, blue-collar town recover from the worst drug epidemic in U.S. history on top of 45 years of deindustrialization? Economists studying national trends say people should simply vacate towns like Hagerstown—and seek work elsewhere.

“The epidemic has not peaked yet by any means,” says Mike Piercy, director of the Washington County Department of Social Services. “If we were somehow able to turn around the [addiction] numbers today, it would take another 20 years to shake off the damage.”

police investigating a burglary on West Franklin Street

o understand the DNA of Hagerstown, you have to go back to the 19th-century industrial boom. Situated near the Potomac River and what was once Western Maryland and West Virginia coal country, Hagerstown served as a vital gateway to the fertile Midwest. The National Road, Route 40, began carrying wagon trains through Hagerstown to the Ohio River Valley in 1818. The steel tracks of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad started carrying locomotives from Baltimore in the same direction, straight through the heart of Hagerstown, two years after the end of the Civil War. The C&O (Chesapeake and Ohio) Canal, which passes through Washington County and primarily transported coal, was already in operation by then, having been completed in 1850.

o understand the DNA of Hagerstown, you have to go back to the 19th-century industrial boom. Situated near the Potomac River and what was once Western Maryland and West Virginia coal country, Hagerstown served as a vital gateway to the fertile Midwest. The National Road, Route 40, began carrying wagon trains through Hagerstown to the Ohio River Valley in 1818. The steel tracks of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad started carrying locomotives from Baltimore in the same direction, straight through the heart of Hagerstown, two years after the end of the Civil War. The C&O (Chesapeake and Ohio) Canal, which passes through Washington County and primarily transported coal, was already in operation by then, having been completed in 1850.

But the current economic picture in Hagerstown stands in stark contrast to the days when it earned its Hub City nickname—when five major passenger and freight lines merged here in a way that resembled the spokes of a wheel. Consider, for example, that three of the four railroad properties on the Monopoly board were spokes in that Hagerstown hub, connecting the city to Richmond, Washington, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York.

In the first decades after World War II, during the early rumblings of the automobile age, Hagerstown continued to thrive, becoming a trucking hub as well a rail hub. Now, however, nearly all of the rails leading into downtown have been removed. After the public schools and hospital, the largest employers in Washington County today are the sprawling Citi and First Data call centers.

a view from the abandoned hospital parking garage across from the antietam street clinic.

Even as other Rust Belt towns decline—losing union jobs, community, status, and a general hope for a brighter future—the numbers in Hagerstown are startling when you step back and look at them. In a Brookings Institution study of 114 metropolitan areas that specialized in manufacturing from 1980-2005, the Hagerstown-Martinsburg (West Virginia) area had the second-highest percentage of industry job change in the U.S., a staggering 70 percent. Meanwhile, health care, housing, and education costs have skyrocketed over the ensuing decades, but wages, adjusted for inflation, have remained essentially flat in Hagerstown, growing just 5 percent in total over that 25-year span.

More than 80 percent of students at three Hagerstown public schools receive free or reduced-priced lunches.

And now, Hagerstown’s unique coordinates, once its greatest asset, play a leading role in enabling its public health crisis. Six years ago, at an I-81 coalition meeting of stakeholders, Western Maryland state police commander Lt. Mike Fluharty coined the phrase “Heroin Highway” to describe Hagerstown’s I-81/I-70 nexus. Stretching from New York to Tennessee and Baltimore to Utah respectively, I-81 and I-70 are two of the longest interstates in the U.S., and they intersect in Hagerstown. It’s these fast-rolling interstates that carry the deadly opioids, including heroin and fetanyl, flooding Maryland’s western counties.

The opioid trade has become so lucrative here that dealers from Baltimore and even New York travel to Hagerstown, and often farther into West Virginia, because they can earn up to $40 more a gram for heroin and a similarly higher profit margin for fake pills, like the counterfeit, fentanyl-laced “Vicodin” that killed Prince. “Dealers now have their own pill presses,” explains Drug Enforcement Administration agent Robert Grob at a recent Drug Take Back Day, a collaboration between the Hagerstown Police Department, county health department, and the DEA that encourages local residents to turn in leftover medication for safe disposal. “All it takes is a little fentanyl—or a microgram of carfentanyl, which is 100 times more potent. They buy the stuff to cut it, the right color dye, and press in a number or an initial, and it looks like the real thing—Percocet or whatever.”

Hagerstown Suns’ Municipal Stadium.

Kristie Lockhard, a 38-year-old recovering addict volunteering at the event, says when she first started using heroin in 1999, she would drive to Baltimore two or three times a day to buy it.

“Now it’s everywhere here,” she says. “It’s a phone call away. They’ll deliver. Quicker than ordering a pizza."

More than 1,000 pounds of prescription medicine is collected in the first two hours of the event, which is held in an empty parking lot outside the county health offices. Two more telltale signs of Hagerstown’s plight are present here as well: The county’s storefront offices sit in an all-but-abandoned shopping center, and nearby is a Superfund site, less than a mile from three public schools, and still in need of remediation two decades after it was added to the EPA’s National Priorities List.

Add to all of this one more factor: Three prisons in Hagerstown, includings two state penitentiaries, have had a habit, according to local law enforcement officials, of leaving ex-offenders in town once they’re released. “It’s a problem,” says former Hagerstown police chief Victor Brito, who resigned in May to lead the Rockville force. “With the highways and economic factors, it’s all a perfect storm.”

a shuttered barber shop on Jonathan Street.

“People began to say, ‘Oh, if it can happen to that family, it can happen to my family.’”

y any definition, the epidemic in this part of Maryland, a state with one of the top five death rates from opioids in the country, is among the worst anywhere. Since the start of the addiction crisis, which now kills more in the U.S. than car accidents and gun violence combined, emergency rescue calls have tripled in Hagerstown.

In 2016 (the most recent year available), an average of 113 prescriptions for opioids were written for every 100 Washington County residents—nearly twice the national average. At Meritus Medical Center outside of downtown Hagerstown, nearly three children a week are born addicted to opioids.

y any definition, the epidemic in this part of Maryland, a state with one of the top five death rates from opioids in the country, is among the worst anywhere. Since the start of the addiction crisis, which now kills more in the U.S. than car accidents and gun violence combined, emergency rescue calls have tripled in Hagerstown.

In 2016 (the most recent year available), an average of 113 prescriptions for opioids were written for every 100 Washington County residents—nearly twice the national average. At Meritus Medical Center outside of downtown Hagerstown, nearly three children a week are born addicted to opioids.

Home to one-fourth of the county’s population, Hagerstown accounts for the majority of those seeking treatment, as well as the majority of overdose fatalities, which included 21 city residents in the first four-and-a-half months of this year—a pace that would, if it continues, triple last year’s total. In a town with two traditional public high schools—North High and South High—it has become the norm for incoming generations to attend several funerals before seeing their first classmate get married. “I cannot count the number of friends who have died after I almost did,” says Katie Wetzel, 27, a recovering addict in Hagerstown who is now married with three kids. “A lot of them are just taking their normal dose and get hit with this new shit cut with fentanyl. They don’t stand a chance.”

The societal ripple effect of the opioid epidemic can’t be overstated, says Piercy, who doesn’t have to look any farther than outside his downtown Potomac Street office window to witness people nodding and passing out. The crisis, he says, is driving a dramatic increase in infant mortality rates, a bellwether for other social problems. “We had 13 infant deaths over the past two years, eight of whom were born substance exposed and later died at home because of neglect or some other cause,” Piercy says. “We have more kids living with their grandparents and a greater need for foster parents. The number of child abuse cases has gone up. I’m not in economic development, but you also can’t help but wonder, how do you build a workforce and attract new businesses—which we desperately need—when this is happening everywhere in your community?”

A sitting train and truck behind a lot along West Franklin Street.

he one place in Maryland that has had a long struggle with heroin use is Baltimore, of course. And for the past two-and-a-half decades, the city has taken a public health approach to addiction, offering methadone programs, needle exchanges, HIV testing, and inpatient treatment opportunities before the pharmaceutical industry dumped OxyContin and other opioids onto a naïve market. The rest of the state did not share that history, and Hagerstown and towns like it are dealing with something entirely new. These kinds of places are where non-college-educated, white working-class people have been dying in increasing numbers from what Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton referred to in their landmark 2015 paper as “deaths of despair”—suicide, drug poisoning, and liver disease—which are reversing the life expectancy progress that the U.S. has seen over the past 50 years. A mortality rate increase for any first-world demographic group had been virtually unheard of for decades, with the exception of Russian men after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a phenomenon blamed on soaring alcoholism rates. It is a cruel twist that Hagerstown, on the receiving end of so much heroin from Baltimore, has such a shortage of addiction specialists that the Wells House, one of the largest outpatient clinics here, utilizes Baltimore doctors via telemedicine to treat its clients.

he one place in Maryland that has had a long struggle with heroin use is Baltimore, of course. And for the past two-and-a-half decades, the city has taken a public health approach to addiction, offering methadone programs, needle exchanges, HIV testing, and inpatient treatment opportunities before the pharmaceutical industry dumped OxyContin and other opioids onto a naïve market. The rest of the state did not share that history, and Hagerstown and towns like it are dealing with something entirely new. These kinds of places are where non-college-educated, white working-class people have been dying in increasing numbers from what Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton referred to in their landmark 2015 paper as “deaths of despair”—suicide, drug poisoning, and liver disease—which are reversing the life expectancy progress that the U.S. has seen over the past 50 years. A mortality rate increase for any first-world demographic group had been virtually unheard of for decades, with the exception of Russian men after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a phenomenon blamed on soaring alcoholism rates. It is a cruel twist that Hagerstown, on the receiving end of so much heroin from Baltimore, has such a shortage of addiction specialists that the Wells House, one of the largest outpatient clinics here, utilizes Baltimore doctors via telemedicine to treat its clients.

Across the country, rural addiction rates have surpassed those in urban areas, yet there is still not a single inpatient drug treatment facility in Washington County.

“People often use the term ‘self-medicating’ to describe why people use drugs or alcohol,” says Ron Zuskin, a licensed clinical social worker and former University of Maryland faculty member who has worked in Western Maryland. “It’s not as conscious a decision as that. But there is often trauma, or simply the stress of living in poverty, that is putting them under intense pressure.”

“It’s not the white picket fence. you can’t find work, can’t pay your bills. who wants to think about that?”

A dog tied up behind Byers Market on North Burhans Boulevard. Men outside a Hammond Street garage.

osh Morningstar could be the poster boy for the use of prescription opioids gone awry. Ten years ago, the Hagerstown native started having seizures once or twice a week that left his muscles tense, his bones aching, and his head feeling like it might explode. Along with a prescription for the anti-seizure medication Topamax, his family doctor prescribed him Vicodin to be taken after each episode.

osh Morningstar could be the poster boy for the use of prescription opioids gone awry. Ten years ago, the Hagerstown native started having seizures once or twice a week that left his muscles tense, his bones aching, and his head feeling like it might explode. Along with a prescription for the anti-seizure medication Topamax, his family doctor prescribed him Vicodin to be taken after each episode.

He liked the feeling the Vicodin gave him and began to sometimes take the pills just for that hydrocodone buzz. The seizures, and the refills, continued for about eight months, then ceased, but Morningstar found himself dependent on the narcotic—physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Over a period of about three years, he went from prescription Vicodin to shooting up heroin. Though extreme, the transition seemed gradual. When his Vicodin prescription ended, he started buying it on the street, until 5-milligram Vicodins weren’t enough. He moved on to 10-milligram Percocet, then 30-milligram. Then he went from eating it to snorting it. Before long, he was buying heroin because it was cheaper than pills, and he went from snorting to injecting it, simply to maintain the same high—and eventually just to function, if you could call it that.

Addictions counselor Lee Green.

He couldn’t hold down a job for more than a month or two, he says, and bounced around from one employer to the next: cleaning bathrooms, painting houses, waiting tables, making pizza.

“October of 2011, I woke up one day and thought, this is the day you die or the day you get clean. I legitimately thought about that for five or six hours that day. I was gonna overdose and kill myself.”

Instead, he sought help by way of Suboxone (the commercial name for a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone), which he considers a miracle. Methadone, he argues, “is a drug just like heroin.” He found an opiate specialist doctor and took Suboxone for about a year, then safely weaned off.

“Life is great now,” he says. He’s married with children and living his dream of being a full-time musician, touring his original folk-country songs across the U.S. But he moved his family to Pennsylvania a couple years ago, leaving Hagerstown behind.

“It’s low-income, and I think it’s hard for people to find and keep employment there,” he says. “It’s not the white picket fence. When you can’t find work, can’t pay your bills—who wants to think about that? Instead, you go get high and forget about it for a while.”

Forty-year-old Brooks Zombro, who has lived in Hagerstown his whole life, puts it another way: “Hagerstown is a manufacturing town, then we lost all those factory jobs our parents and grandparents had, [and] it has become a playground for big box retail that has all but eliminated and destroyed our downtown’s small business district. We kind of got shit pie handed to us.”

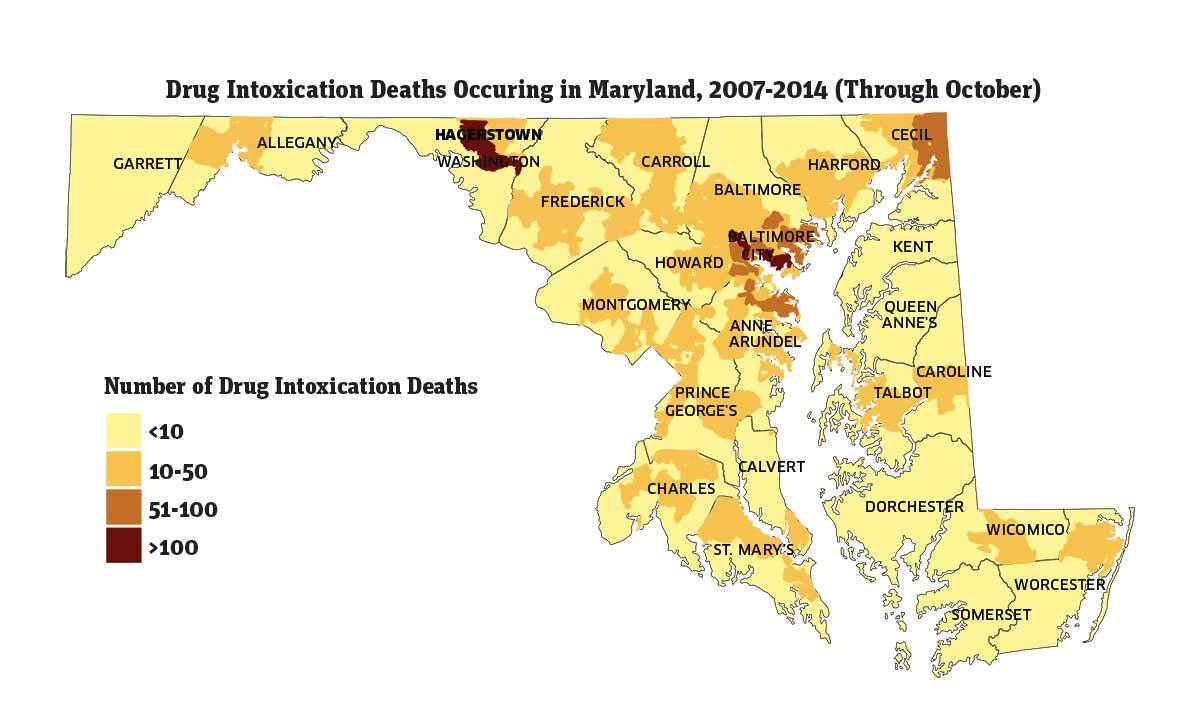

Source: Maryland Vital Statistics Administration

HAGERSTOWN MORE CLOSELY RESEMBLES A MICROCOSM OF BALTIMORE—ESSENTIALLY A SMALL TOWN WITH BIG-CITY PROBLEMS, CONTINUALLY IN SURVIVAL MODE.

s the former managing editor of Hagerstown’s daily newspaper, The Herald-Mail, Dave Elliott witnessed firsthand the city’s downward spiral. He blames forces beyond the city’s reach, as well as futile and often misguided leadership. Plainspoken but good-natured, and a well-respected journalist, Elliott started at The Herald-Mail in 1970. He moved to The Frederick News-Post in 1989 but lived in Hagerstown until 2000.

s the former managing editor of Hagerstown’s daily newspaper, The Herald-Mail, Dave Elliott witnessed firsthand the city’s downward spiral. He blames forces beyond the city’s reach, as well as futile and often misguided leadership. Plainspoken but good-natured, and a well-respected journalist, Elliott started at The Herald-Mail in 1970. He moved to The Frederick News-Post in 1989 but lived in Hagerstown until 2000.

Big out-of-town industries such as Fairchild Aircraft, which once employed 10,000 people and closed its plant in ’83, and Mack Trucks, which arrived in 1961 (and still makes trucks here, although it employs fewer people), were controlled from a distance and had no stake in the community, Elliott asserts.

Those kind of manufacturing jobs generally pulled up stakes for cheaper labor in the South or overseas, a trend that has continued.

Politically, Washington County has always tilted right. George Wallace campaigned here in 1968 and 1972. President Donald Trump spoke to a packed hangar at Hagerstown Regional Airport during his campaign in 2016 and won the county vote by a 2-1 margin.

councilwoman emily keller.

Herman Mills, a Republican mayor from 1965-1973 who owned several gas stations and stores, was a “sort of kingpin of the local ruling class,” as Elliott puts it—and the last in a long line of businessmen and factory owners investing in Hagerstown. “From the early 1970s onward, there was a vacuum—economically, socially, politically, culturally. There were a few people dedicated to establishing a Maryland orchestra, a few people trying to revive the Maryland Theatre. There were things going on, but no cohesiveness at the top.”

One (seemingly) solid mayor, Republican Donald Frush, who served from 1981-1985 and was known as “the Father of Planning” in Washington County, disappeared during his campaign for a second term and was found by a reporter at a Johns Hopkins psych ward.

Mayor Richard Trump (no relation to the president), who ran for office on a slate that promised to return God to City Hall, abruptly resigned without explanation after nine months in office in 2006.

One of the biggest mistakes city officials made was failing to sufficiantly upgrade Municipal Stadium, the nearly 90-year-old home of the minor league Hagerstown Suns, or build a new ballpark downtown. The team lost its Orioles affiliation in the 1980s when the O’s said goodbye to Hagerstown and hello to nearby Frederick. (Currently affiliated with the Nationals, the Suns draw a South Atlantic league-low 896 fans per game; Frederick led the Carolina League in attendance from 2012-2016, attracting nearly 5,000 fans a game.)

For a century, Hagerstown had been the dominant city, and Frederick a little cow town. In recent decades, they’ve swapped roles. Frederick, which seems worlds away rather than a mere 20 minutes, has benefitted from its MARC train station, which has grown the town into a bedroom community of D.C. It’s also close enough to Baltimore that people make the I-70 commute. Because of that, its residents have more money and higher expectations, and a strong restaurant base and downtown arts and culture district has grown there, sustained by its community. “Hagerstown is still a meat and potatoes kind of place,” says Elliott.

But after 50 years of decline, Elliott and others say downtown is finally showing signs of recovery, even if it is a long road ahead.

The rear of North and Locust Food Mart. A Hagerstown pawn shop.

orking with Philadelphia-based Urban Partners, the city has put together a 10-year City Center Plan, which began in 2014, to enhance the town’s quality of life and attract new developers, investors, and businesses. With a projected $125 million in investments needed to fully develop the proposal—a big if—the project, according to city officials, has the potential to create 875 jobs. Eight planned downtown catalyst projects include an expanded City Farmers Market and the creation of a cultural trail, part of which has already been implemented. A huge component of this initiative includes a $40-million effort, started in 2017, which will expand three key institutions—the University System of Maryland at Hagerstown, the Maryland Theatre, and Barbara Ingram School for the Arts—with a slated completion date of spring of 2020.

orking with Philadelphia-based Urban Partners, the city has put together a 10-year City Center Plan, which began in 2014, to enhance the town’s quality of life and attract new developers, investors, and businesses. With a projected $125 million in investments needed to fully develop the proposal—a big if—the project, according to city officials, has the potential to create 875 jobs. Eight planned downtown catalyst projects include an expanded City Farmers Market and the creation of a cultural trail, part of which has already been implemented. A huge component of this initiative includes a $40-million effort, started in 2017, which will expand three key institutions—the University System of Maryland at Hagerstown, the Maryland Theatre, and Barbara Ingram School for the Arts—with a slated completion date of spring of 2020.

When the University System of Maryland satellite campus at University Plaza was established in the city center in 2005, it was the first time anything like that had moved into town in decades: something big, with money behind it and staying power. A block away, two restaurants that would become staples—Jone and Don Bowman’s Bulls and Bears and E. Jay Zuspan III’s 28 South—soon opened. In 2009, an old theater was transformed into BISFA, a magnet arts high school.

As the former Supervisor of Visual and Performing Arts for Washington County Public Schools, Rob Hovermale was involved in conversations as early as 2000 about opening a public arts high school in Hagerstown—talks that were largely dismissed at the time.

“Had we not gotten this building donated, it never would’ve happened,” says Hovermale, who’s lived in Hagerstown most of his life and now serves as principal of BISFA.

Recovering opioid user Katie Wetzel.

The school started with 85 students but this year surpassed 300, even though that meant holding classes in hallways and stairwells. They’re bringing in students from nearby counties and occasionally out of state. “We have a long way to go, but the school has brought life downtown,” Hovermale says. “It’s a huge step forward.” A block away, the City of Hagerstown opened the artist-run Engine Room Art Space and four artist apartments above it in 2015, which also breathes some life into the city.

“You’ll see people dressed up nice to see a play or film, and you have addicts walking around,” says Matthew Hast, a sculptor who lives at Engine Room. Daily, he watches people, mostly in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, selling and scoring drugs in the city’s central parking lot behind the gallery.

Another resident artist, Anthony Jones Jr., is a recovering cocaine addict and alcoholic who credits art—and Engine Room—as part of his salvation, giving him a sense of purpose and allowing him to be creative rather than self-destructive. “This place is a blessing. We get to engage and feel like we’re being a positive influence on the city.”

These ongoing efforts build on one of Hagerstown’s legacy assets, the lush City Park, utilized year-round, as well as the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts therein, where the new Cultural Trail begins before it winds toward downtown.

“Having beautiful open spaces is important, and it’s important to have a connection to your community,” says city engineer Rodney Tissue, who moved to Hagerstown in 1986 and raised his two daughters here. The trail, which he helped develop, is primarily for economic development but also gives residents a sense of place and pride in their community.

Although the city has seen little interest from developers for the empty lots along the trail, Tissue says several nearby buildings have been purchased and rehabbed. “I’ve seen growth in investor confidence,” says Director of Community & Economic Development Jill Frick Thompson, attributing it to the city’s 10-year plan.

Whether these efforts, which remain largely public investment—schools, libraries, parks—can spark enough commercial interest to compete with the Valley Mall, the two Walmart Supercenters, and the Premium Outlets remains to be determined. If effective, they will be a start in rebuilding Hagerstown’s economy and, ultimately, its quality of life. Indirectly, they could have a hand at reversing the public health crises in the long run, civic leaders say.

icki Sterling, director of the Washington County Health Department’s Division of Behavorial Health Services, says the turning point for the county in addressing the opioid epidemic was the death of former Hagerstown police sergeant Kevin Simmers’ daughter, Brooke, who overdosed on heroin 10 days after she had been released from a four-month prison stay. “People began to say, ‘Oh, if it can happen to that family, it can happen to my family,’” Sterling says. “This was a normal kid, the daughter of a respected ex-city cop. My daughter went to school with her.” Up until that point, most people in Washington County viewed addiction as a criminal justice issue. Including Brooke’s father.

icki Sterling, director of the Washington County Health Department’s Division of Behavorial Health Services, says the turning point for the county in addressing the opioid epidemic was the death of former Hagerstown police sergeant Kevin Simmers’ daughter, Brooke, who overdosed on heroin 10 days after she had been released from a four-month prison stay. “People began to say, ‘Oh, if it can happen to that family, it can happen to my family,’” Sterling says. “This was a normal kid, the daughter of a respected ex-city cop. My daughter went to school with her.” Up until that point, most people in Washington County viewed addiction as a criminal justice issue. Including Brooke’s father.

Christina Trenton Nee, COO, and Charlie Mooneyhan, CEO, of Wells House.

Simmers, an outgoing, thick-shouldered 53-year-old, joined the military out of high school in the early 1980s with the intention of going into law enforcement. “I fully bought into the War on Drugs and what Reagan was doing,” he says. “I wanted to be in narcotics. I wanted to knock down doors and haul bad guys off to jail, and that’s what I did for 30 years.”

Since his daughter’s death, Simmers and Brooke's stepmother, Dana, have been very public about sharing their experience, sparing none of their family’s worst moments and pain. Their daughter, who grew up playing soccer and basketball, became hooked on pills by 18 and then turned to heroin. She tried treatment and rehab several times, and even laid down on the family’s lawn once, begging her father to shoot her to put her out of her misery. “You can imagine as a police officer and a father how I felt,” Simmers says. “It’s like watching a slow train crash coming that you don’t know how to stop.”

For the past three years, the Simmerses have been working to build Brooke’s House in Washington County. The 16-bed treatment project for women is partly to honor their daughter, who once shared her wish of getting off drugs and opening such a center with her parents, but it is also borne of frustration, as the family repeatedly struggled to get the help their daughter needed. Brooke died while waiting for insurance approval for a $700 monthly shot of Vivitrol, which reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

According to a 2016 report from the U.S. surgeon general, only one in 10 people with an addiction problem receives treatment.

“I’ve been a right-wing Republican all my life,” Simmers says. “But how many people do you know that have been attacked by a terrorist? Or an illegal immigrant? Nobody I know. Now, how many families do you know that have been affected by addiction? That’s everyone I know. This isn’t political. This is across the board—and I’ll be the first to agree that attitudes are changing because more white people are dying—that’s totally fair. I was on the other side, and I get it, and people have every right to make that point.”

Kevin and Dana Simmers at the future site of Brooke's House.

Earlier this spring, Keller, the city councilwoman who lost her best friend to an overdose, announced that the city would be joining several hundred municipalities, counties, and states in pursuing legal action against the nation’s largest drugmakers, alleging that they played a key role in launching the opioid epidemic. She highlighted not just the personal toll of the opioid epidemic on families but decreasing property values, its effect on businesses and workforce participation rates, and the immense strain placed on the city’s police, EMS, and fire department budgets. The City Council will likely be forced to raise property taxes again this year.

In an emotional press conference, she pointed the finger directly at the pharmaceutical companies, including Purdue Pharma, which hired hundreds of sales representatives to promote their product and has been accused of using misleading information to hide the drug’s addiction potential.

“This epidemic, largely caused by the pharmaceutical industry’s complete lack of accountability or care about anyone or anything other than their pockets, has wreaked havoc on my city,” Keller said. (In 2007, three Purdue executives pleaded guilty to federal charges related to the misbranding of OxyContin and paid $34.5 million in fines, while the company agreed to pay $600 million to resolve a Department of Justice investigation.) The first three municipality lawsuits against drugmakers—all Ohio cases—are scheduled to be heard in U.S. District Court in Cleveland early next year. Still, they are something of a Hail Mary pass for municipalities. It's hard to imagine Hagerstown and similar cities receiving restitution anywhere near the true cost of the opioid epidemic and officials acknowledge that.

Later, outside a Rotary Club meeting, Keller talks more optimistically about the city’s current efforts to tackle the crisis.

She mentions the increased training for Narcan, a medication that can prevent fatal overdoses, across the city. She also cites the new safe needle program implemented by the county health department—albeit over the objection of a couple of state delegates—to combat Hepatitis C and HIV infections. She discusses plans for the rollout of a new awareness program, Washington Goes Purple, a symbolic color adopted by opioid prevention advocates, geared toward steering youth away from substance abuse.

She talks enthusiastically—and genuinely—about the $40-million downtown revitalization effort and Hagerstown’s future. “To me, the urban improvement project is huge. We’ve been struggling for decades and hopefully this will get the ball rolling,” she says. “We need to maintain a sense of hope. It’s hope or heroin out here.”