Black artists are finally receiving recognition in the mainstream art world, but it has been a long uphill battle toward equity, and it's one that they’re still fighting.

Arts & Culture

The Color Line

Black artists are finally receiving recognition in the mainstream art world, but it has been a long uphill battle toward equity.

On a rainy summer afternoon, Myrtis Bedolla, a highly respected gallerist and art dealer, sits in her second-floor office overlooking North Charles Street to talk about the shifts she’s witnessed in her 30-plus years in the field.

Myrtis Bedolla at the opening of Ronald Jackson's exhibit at Galerie Myrtis. —Ken Fletcher

Books and files on black art and its history line the walls. A piece by Anna U. Davis, one of the artists she represents, hangs prominently above her desk. One floor below, brick walls display oversized, solemn portraits of black men and women by figurative painter Ronald Jackson, as part of his solo show, Profiles of Color III: Fabric, Face, and Form. This floor below her office and home is Galerie Myrtis, the gallery she founded in 2006 in Washington, D.C., and moved to Baltimore two years later.

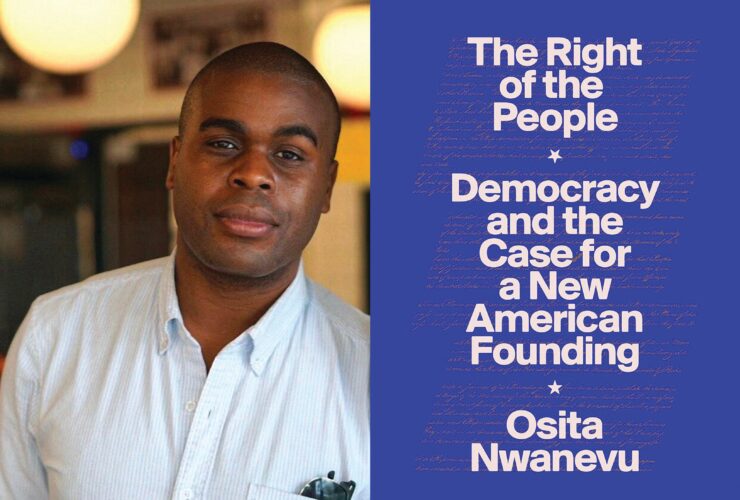

It’s a few weeks after the publication of the controversial New York Times article “Why Have There Been No Great Black Art Dealers?,” and though hints of frustration and disappointment come through at times, Bedolla’s eyes remain soft and thoughtful, her voice sweet, her mind and body composed, as she talks about how black art has been ignored by major institutions because our country is still living with the vestiges of slavery.

“This art is the visual pedagogy for teaching the African-American experience—our past and current experiences—but museums have failed to embrace that truth, that voice,” she says. “It’s finally starting to be seen as a part of American history, rather than just African-American history. We’re being put into context.”

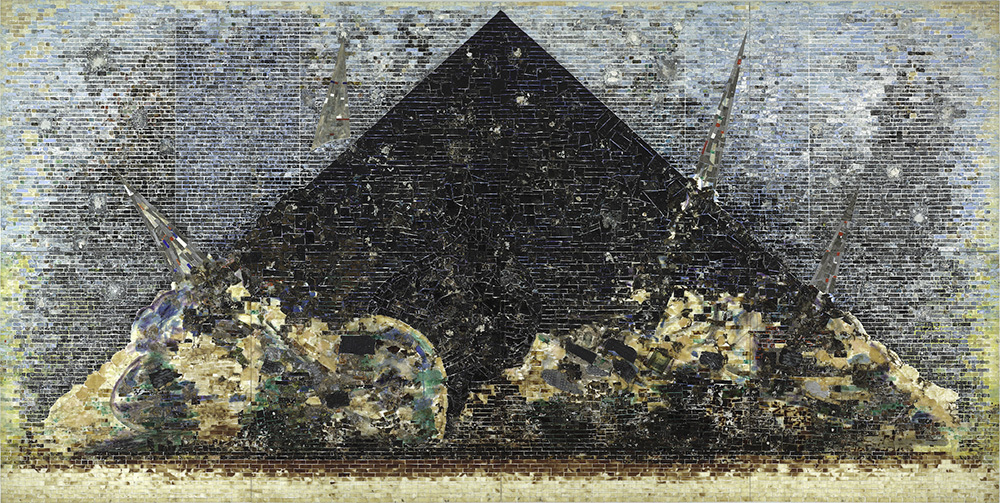

She cites The Baltimore Museum of Art’s recent retrospective Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963-2017, a major ticketed event that moved from Baltimore to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in September.

“The public hasn’t been able to engage in that work because of black prejudices and stereotypes. But people want to engage in it. Black art is so powerful and engaging—it just is—and we’re all better for being exposed to it,” Bedolla says. “Somehow it’s been believed that the work of a black artist is not relatable to a white person. Wouldn’t it be beautiful if we could take the race out of it and just allow the experiences to come forth? As human beings, we could see how we fit into that narrative and how much we’re connected and alike rather than how different we are.”

Like many others across the nation, she has made it her life’s mission to celebrate and support emerging to mid-career African-American artists by exhibiting their work and connecting them to collectors.

“It’s rewarding work to see an artist rise,” she says. “If I’ve done my work to help build the artist’s career, I’m happy if they move on and find their way into the limelight.”

She knows this feeling firsthand. She once represented Baltimore-based Amy Sherald, whose portrait of Michelle Obama launched her into art-world stardom overnight, with rabid collectors and dealers from around the world wanting to purchase her work, which she makes in her studio at Motor House in Station North.

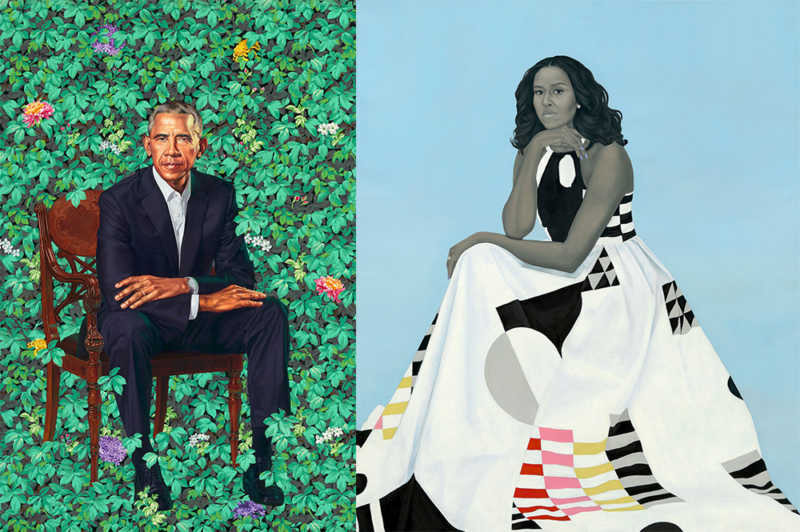

When the official National Portrait Gallery portraits of the Obamas were unveiled in February, both were painted by black artists—Sherald and Kehinde Wiley—a first in our country’s history. The museum experienced record-breaking attendance in the weeks that followed—so much, that Sherald’s portrait had to be moved to accommodate the crowds.

Brion Gill stands at the site of the proposed Black Arts and Entertainment District. —Mike Morgan

The time is ripe for such a recognition, if long overdue.

Although black music has been a part of American popular culture for decades—in part because of its accessibility—art, film, theater, and literature by black artists has not had the same fortune. But in the past five to 10 years, the popularity of black-made work is on the rise. Moonlight, a story about the coming-of-age of a black gay man, won Best Picture at the Academy Awards in 2017, and the 2016 film Hidden Figures, which tells the true story of three African-American women at NASA during the Space Race, dominated the box office in sales, surpassing La La Land and Jason Bourne. In 2016, Hamilton, the Broadway musical featuring actors of color rapping as they portray America’s founding fathers, earned a Tony for Best Musical, a Grammy for Best Musical Theater Album, and a Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Nowhere does black work seem to be exploding so suddenly as in the visual arts. A recognition of black art and culture is surfacing inside America’s major museums, infiltrating the mainstream art world. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture opening in Washington, D.C., is a prime example. It not only validated work by black artists but confirmed that the public wanted to see this work that had been neglected; it opened in September 2016, and free passes sold out through March, with 30,000 people trying to get in on some days—four times more than the museum had predicted and could accommodate.

“We as black artists have not had the luxury of just being artists.”

In addition to Sherald, Baltimore’s Paul Rucker is another important Baltimore figure in this emerging scene. Awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, he explores slavery and the black narrative in his work, and his exhibition Rewind, a collection of life-sized KKK outfits made with colorful, patterned material in his studio at the Creative Alliance, has toured the nation.

Stephen Towns, who works from his studio at Area 405 in Greenmount West, landed a career-making solo show of his story quilts at the BMA this year. The fiber art pieces, which tell the story of Nat Turner's slave rebellion, have a distinctly painterly quality and have been called a genre all their own by Mark Bradford, a black abstract painter who represented the U.S. at the 2017 Venice Biennale.

And we can't forget Joyce Scott, long-known in Baltimore for her sculptural beadwork and named a MacArthur Fellow in 2016.

Still, “the lack of museums hiring black curators is egregious,” says Bedolla. “I’ve seen art not interpreted properly, not even labeled properly. We have to have black people in place to bring equity to museum collections.”

The BMA is one of the country’s major institutions leading this shift. Christopher Bedford, who was named director of the BMA in 2016, recognized the importance of incorporating more diverse work into the museum, as well as its staff and board (Sherald was appointed as a trustee to the board in January), and he made this integration part of his mission.

“Some of the most important work being made right now—abstract and figurative—is by black Americans,” says Bedford, who is British. “Great art is bred where the artist is closest to their core humanity, and I think sometimes adversity breeds that.”

Museums, like the art installations within them, Bedford asserts, should be site specific, their context provided by geography. To have a museum in Baltimore, a 63 percent black city at the most recent Census, that is showing work by nearly all white artists (as genius as that work may be) is an inaccurate representation of the diverse community it’s meant to serve, he argues.

In spring of 2018, the BMA deaccessioned seven works by white male artists (Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Franz Kline, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski) in order to acquire contemporary pieces by predominantly black artists, among them Mark Bradford, Zanele Muholi, John T. Scott, and Jack Whitten.

The museum’s programming has also shifted in recent years to include art talks with Towns, Sherald, and Bradford, as well as an Afrofuturism discussion with Ta-Nehisi Coates in May (that sold out) and an Afropolitanism-themed Art After Hours party in June that Baltimore music artist Abdu Ali headlined. Its fall schedule is looking just as diverse, showing new work by artists of color, including Maren Hassinger, Ebony G. Patterson, and Tavares Strachan, plus a major exhibition by Mark Bradford.

“I said, sort of flippantly, at a board meeting, ‘Baltimore is ready for this work,’” Bedford says. “Amy Sherald said, ‘This city has been ready for this work for decades.’”

Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Dwell: Aso Ebi. 2017. The Baltimore Museum of Art purchase

It’s not as if the art wasn’t being made. The earliest documented professional African-American painter, Joshua Johnson, lived in Baltimore in the 1700s. There have been black artists, dealers, gallerists, and scholars here and across the nation for decades—laboring, chipping away at what some call “the racial mountain”—but until recently they’d been overlooked by the predominately white institutions that largely control the art world.

David Driskell sees black art as the last element in American visual culture that society as a whole has not explored in more detail—and a last frontier for collectors who are beginning to ask what else is out there and also wanting to fill the gaps in their collections, now that black art is being valued. “You look at the omissions and the misrepresentations, and people in good will are trying to correct that mistake,” he says.

A renowned scholar of African-American art, Driskell, 87, attributes the rise in popularity of black art to a growing global interest in it, and America is just catching up. Major museums across the world, in European and Asian countries especially, have shown more interest in African-American work over the past decade, featuring it in major exhibitions, such as 2017’s Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at the Tate Modern in London. (Worth noting: Mark Bradford’s work sells for millions in Europe, on a par with white artists, but it goes for much less in the States.)

“There’s an explosion going on worldwide, and America doesn’t want to be left out,” Driskell says with a chuckle. “We’re still, unfortunately, tied up with race as a factor, but they’re leading us away from our set ways. Our history was so convoluted, we had to go back and look at black slavery and the black experience.”

When Driskell was an art student at Howard University in the 1950s, the chair of the art department, James A. Porter, considered the founding father of the field of African-American art history, told him, “You’re a good painter, but you also have a good mind, and we need people to help define and redefine the field,” Driskell recalls.

Driskell has since devoted his entire life to contextualizing the work of black artists, as have others, such as art historian Leslie King-Hammond, who founded the Center for Race and Culture at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

“We as black artists have not had the luxury of just being artists,” Driskell says. “We have to help define the field and keep the light burning. Otherwise it would go out.”

Roberto Lugo at the wheel. —Walters Art Museum ; Joy Davis, founding director of Waller Gallery. —Mike Morgan

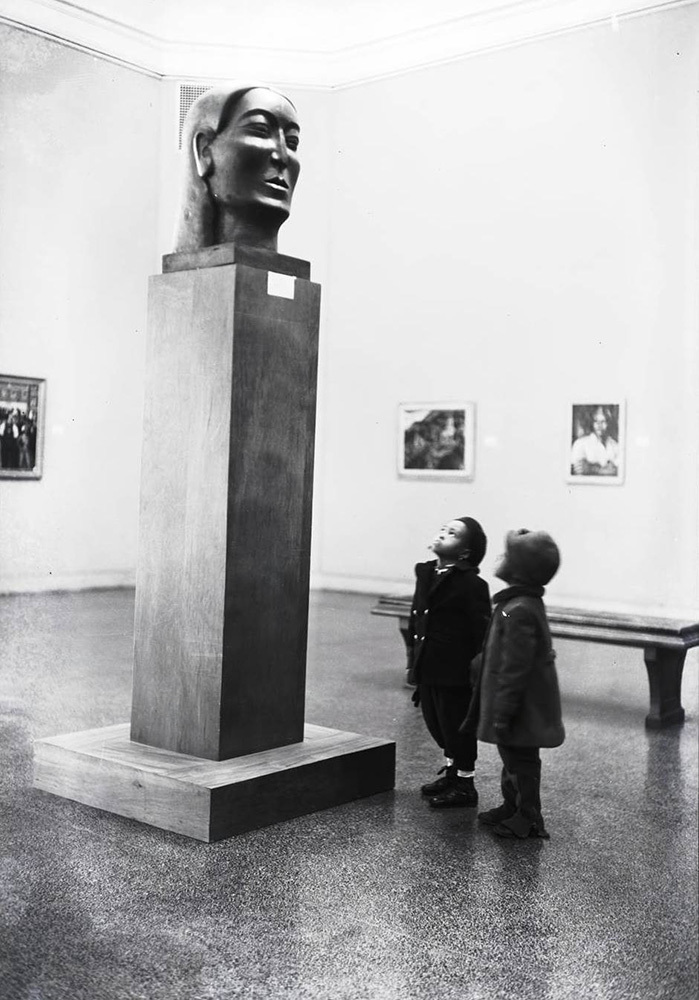

In 1939, the BMA hosted one of the first major African-American art exhibits in the country: Contemporary Negro Art. The board at the time sent a survey out to the community, asking what Baltimore’s people wanted to see in its art museum. Feedback urged the BMA to show work by black artists, and so in a collaboration among the board, the Harmon Foundation, and “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” Alain Locke, the BMA exhibited more than 100 works by 29 black artists, among them Jacob Lawrence and Hale Woodruff.

In honor of this history, a condensed exhibit, 1939: Exhibiting Black Art at the BMA, is on display now through Oct. 28 at the museum, featuring more than a dozen pieces by artists included in the original show.

“These artists might not have the name recognition of Jack Whitten or Mark Bradford, but Whitten and Bradford come from that lineage,” says BMA prints, drawings, and photographs curatorial assistant Morgan Dowty, who curated 1939. “The BMA is being very intentional about being inclusive,” she goes on. “This was a moment in 1939 when we saw something very similar.”

Jack Whitten. 9.11.01. 2006. The Baltimore Museum of Art purchase

Meanwhile, nearly 80 years has passed, and aside from the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African-American History and Culture, the only major museum in Baltimore that has consistently shown work by black artists, is the American Visionary Art Museum, which opened in 1995 and exhibits “outsider” or “naive” art—work not by nationally recognized, sought-after artists but those who are self-taught, and in many cases unknown.

The Lewis, the second-largest museum of its kind on the East Coast after the National Museum of African American History and Culture, is known primarily for its historical collection and less for its contemporary art holdings but has nonetheless served an indispensable role in the city for black artists, exhibiting work by the likes of Devin Allen, Amy Sherald, and Joyce Scott.

“I think artists are the most important chroniclers of our history,” says Jackie Copeland, director of education and visitor services at the Lewis. Then, more frankly, she adds, “It’s wonderful that these artists, like Amy Sherald, are going into major museums and white galleries, and white dealers are now validating them, but the black community has been valuing them for decades—and now we’re being priced out of the work.”

Copeland worked at The Walters Art Museum about 10 years ago and helped them to identify and acquire four pieces by African-American artists, she says, to diversify the collection there.

When 1 West Mount Vernon Place, the newly revitalized wing of The Walters (formerly known as the Hackerman House), was unveiled in June, curators went to great lengths to research the history of the 19th-century mansion and include, through visual art and an app for a self-guided tour, the stories of both its wealthy, soiree-throwing owners and the slaves who lived and worked there.

Work by African-American ceramic artist Roberto Lugo—who grew up in a rough neighborhood in Philadelphia and entered art by way of graffiti—is given prominence in the new space, merging past with present through his pieces depicting such cultural figures as Frederick Douglass.

Former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama's portraits. —National Portrait Gallery

Amy Sherald. Planes, rockets, and the spaces in between. 2018. The Baltimore Museum of Art purchase

In Baltimore, the stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue near Penn-North remains, in many ways, a vital component to the heartbeat of Baltimore’s culture, a constant whose history spans 100 years. Jazz and blues artists, among them Duke Ellington, Etta James, and Louis Armstrong, came through this area to perform at the Royal Theatre; Warner’s Metropolitan Theatre screened first-run films here; Rainbow Theatre, later named Lenox Theatre, provided a venue for film and vaudeville performance; the Sphinx Club operated as one of the first black-owned nightclubs in the country.

Today, the legendary Arch Social Club, commonly said to be the oldest continually running black nightclub in America, stands at the intersection of Pennsylvania and North Avenue, where hip-hop blasts from cars and handheld speakers, and massive murals and graffiti art line every block.

This cultural hub was also ground zero for the 2015 protests following the death of Freddie Gray, as well as the riots in ’68, when scores of clubs and prominent businesses either permanently closed or moved elsewhere. Where the Royal Theatre once stood is now a grass field, the only remnant being a marquee standing tall in the lot’s corner. A lone statue of Billie Holiday singing stands across the street.

“I don’t think this area ever bounced back,” says Brion Gill, an activist and spoken word artist who goes by Lady Brion. “It gained the narrative of being this crime-ridden area where you don’t want to go, but that’s just not the narrative that I see.”

She wants to help this stretch along Pennsylvania Avenue—from Dolphin Street up to North Fulton Avenue, which includes such anchor institutions as the Shake & Bake roller rink; the Avenue Bakery, which hosts jazz; Upton Boxing Center; Jubilee Arts, which holds art and dance classes; and Avenue Market—reclaim its former narrative by designating it as an official Black Arts and Entertainment District. She and others in the Baltimore group Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle are in the midst of the application process through the Maryland State Arts Council and will learn in December if it receives the designation, which would make it the fourth recognized arts district in Baltimore, alongside Highlandtown, the Bromo Tower, and Station North.

“I want to revitalize the economic engine of West Baltimore and bring it back,” Gill says. “It had everything in the recipe for an arts and entertainment district.”

On a larger scale, the MSAC is disbanding the diversity outreach committee it formed five years ago, which had been created to ensure that the council was inclusive about whom it served. “In our new strategic plan, cultural equity is woven within everything we do,” says Carla Du Pree, who had chaired the committee. “We decided we shouldn’t need a separate committee for that.”

The same conversations are being had among the board of directors of the Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance, she says, where she serves as a board member, and at CityLit Baltimore.

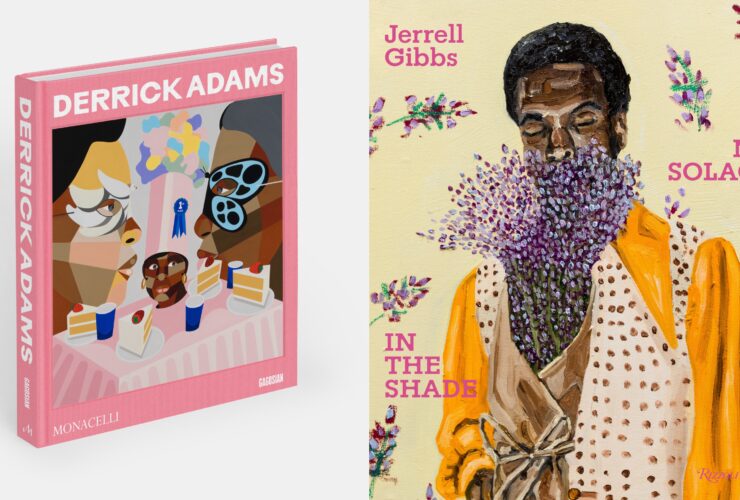

Through her work at the MSAC, GBCA, and as director of CityLit, Du Pree has worked hard to support underrepresented artists, having witnessed inequity firsthand. She’s helped to diversify the featured writers and audiences within CityLit but notices that in a general context, authors of color don’t have the advantages that white writers do. A recent book launch of a white author packed 100 or so people into a Baltimore club, she recalls. “It was beautiful. But I realized I was the only person there of color outside of the help, the servers. A lot of books were getting sold, and I just wondered, for a black writer, how that happens. It would be nice to see black writers supported in that same way.”

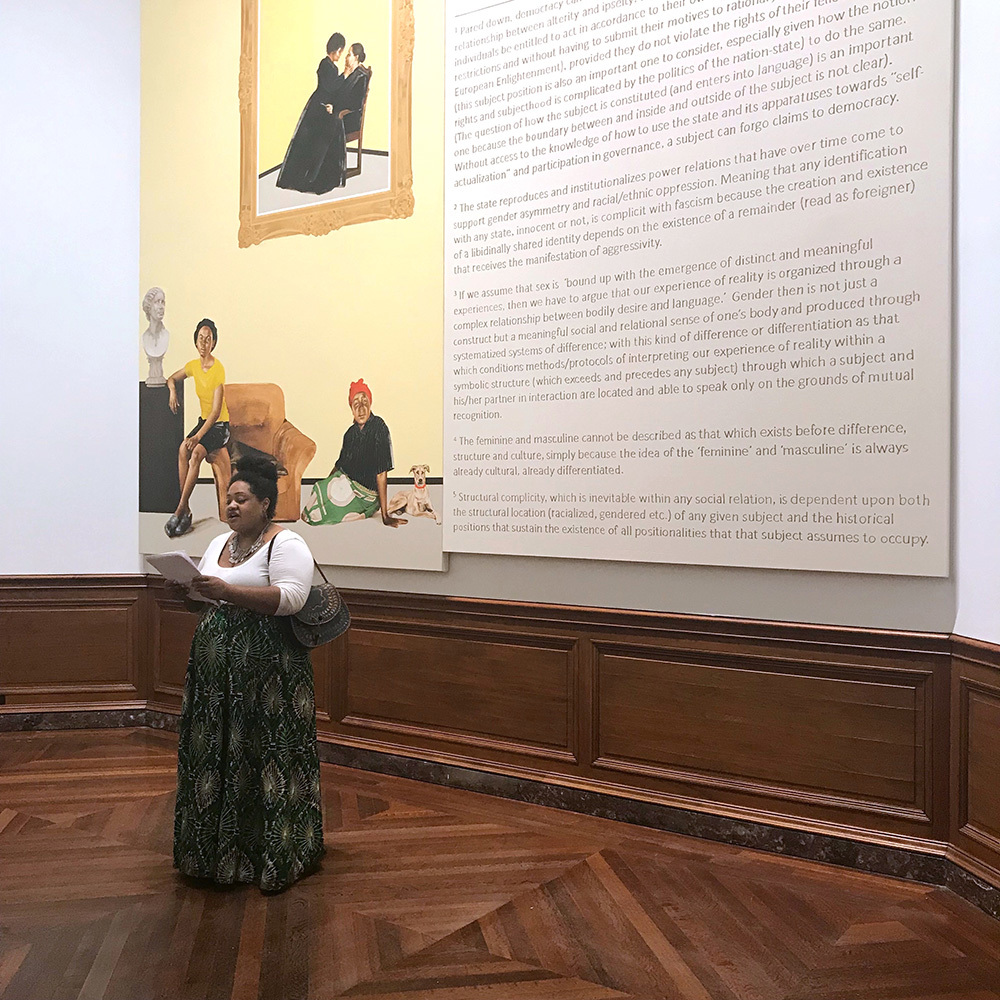

Saida Agostini reads her poetry during The Baltimore Museum of Art’s Afropolitanism-themed Art After Hours in June. —Lauren LaRocca

Even with growing successes in the black arts arena—the Jack Whitten retrospective, the BMA’s recent acquisitions, even the record-breaking sale earlier this year of a piece by African-American artist Kerry James Marshall at Sotheby’s (scooped up by Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs, no less)—those within the network of black creatives are quick to ask: How much of the financial benefits of these shows and sales trickle down to black galleries, black dealers, or the laboring artist—i.e., the black communities?

“Are these museums looking to black galleries to purchase art? For the most part, no,” Bedolla says. “Most of these artists are represented by white galleries. When artists reach a certain level, the white galleries come in and harvest them, as I call it, even though black galleries have done the lion’s share of the work.”

And aside from a select few—Jean-Michel Basquiat, Romare Bearden (whose mural Baltimore Uproar is at the proposed Black Arts and Entertainment District site, and whose work will hit the Lewis in November for a major solo exhibit)—how long overdue is the recognition of these artists?

Joyce Scott’s work is now gradually being collected in places of honor, but, in the opinion of several artists and scholars here, not enough.

Same with D.C.-based Sam Gilliam.

Abstract expressionist Norman Lewis had been at it for a long time before getting attention, and the value of his work is just beginning to increase; his record is $1 million, while that of his white contemporary Jackson Pollock is $200 million.

Still, it’s looking like the next generation of artists—the Amy Sheralds and Paul Ruckers of the world—are rising into the spotlight more quickly than their predecessors, in part because of the groundwork that has been laid by black gallerists, dealers, and scholars over the past 100-plus years—major players not just in Baltimore but across the country: art dealers June Kelly and the late Merton Simpson; The Studio Museum in Harlem’s director and chief curator Thelma Golden and former president Lowery Stokes Sims; and going back further, Alonzo Aden, curator at Howard University’s Gallery of Art, one of the first black art galleries in the country.

Historically black colleges and universities—particularly Fisk University, Hampton University, and Howard University—were among the first places to provide a space to exhibit work by black artists.

“Historically, we didn’t have the necessary income to sustain galleries. The infrastructure is still very weak but getting stronger,” Bedolla says.

Children viewing Ronald Moody’s Midonz (1937) at The Baltimore Museum of Art’s Contemporary Negro Art exhibition. 1939. Photograph Collection, Archives and Manuscripts Collections

Some younger black artists aren’t waiting for the gatekeepers of the art world to acknowledge them; they’re creating cultural institutions of their own. The Fray opened this summer on a residential street in Reservoir Hill. Founders describe the space as the “headquarters to the Baltimore renaissance,” made specifically by and for black creatives.

Bright and cozy rooms—each adorned with plants, paintings by local artists, tables, and sofas—are designated by craft: a reading/writing room, the “Messy Room” (i.e., an art space), a lounge for conversations and meetings, and a room and balcony for music jams.

“It’s important to have designated safe spaces,” says cofounder and co-owner Diamon Fisher, who’s in her 20s and of Afro-Latina descent. She’s been working alongside an advisory board of more than a dozen people—representing the visual, curatorial, literary, fashion, and culinary arts—to create a vision for the space, which is open to the public on a $5 drop-in basis.

The Fray is about more than art; it’s about fostering culture and dialogue in a nurturing environment. Shoes are left at the door. A communal altar invites guests to give or receive blessings or smudge themselves with sage. There are Self-Care Mondays.

“artists are the most important chroniclers of our history.”

In similar fashion, young African-American scholar and artist Joy Davis opened Waller Gallery this spring on a residential block of North Calvert Street, envisioning it as providing a community space where the visual art and coinciding programming will generate conversation, not just sell paintings. She primarily features work by artists of color, including those of Chinese and Vietnamese descent, for instance, and frankly is drawn to any artist who has been seen as “other.”

Davis grew up in Baltimore County but spent the past several years in New York. When she returned, she expected to see mostly white artists at her gallery events. When she’d lived here before, she knew of black artists and spaces, like Jeffrey Kent’s former Sub-Basement Artist Studios, but saw the scene as being “super white,” she says. “Things like Wham City would get covered by media, it seemed like, every month. But African-American artists would only get a mention once every year or two. Like, Joyce Scott was here for how many years?”

Nevertheless, her events have brought in a diverse crowd, not just racially but also age-wise.

Still, she says, “It’s hard for us. We’re always the last to be called for a panel discussion—and it’s because they need diversity and suddenly have to find a black or brown scholar,” she says.

Like many other black art scholars who came before her, she ultimately wants to see the integration of all marginalized communities, a world where there are not “black art” shows or “all-women” shows but simply shows that include important work by everyone.

“Black art is American art, and that is the larger context,” Driskell says. “And don’t leave out women or Asians or Latinos. They, too, in the words of Langston Hughes, ‘sing America.’ And they sing it with a great song.”