Arts & Culture

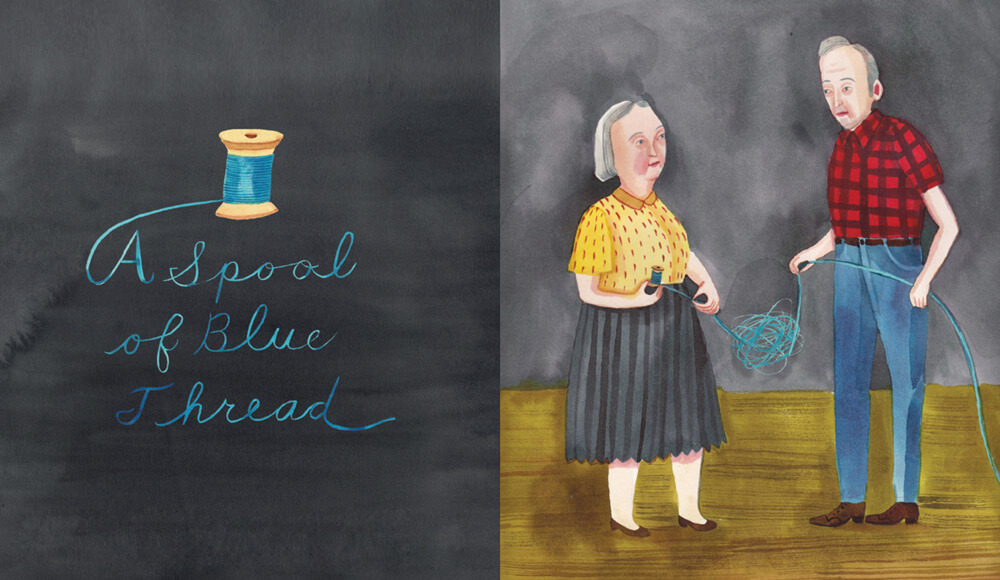

A Spool of Blue Thread

A sneak preview of Anne Tyler's 20th novel, which is, not suprisingly, set in Baltimore.

Anne Tyler published her first novel, If Morning Ever Comes, 51 years ago. Since then, she has ascended to lofty literary territory, winning the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1985 (The Accidental Tourist) and the Pulitzer Prize four years later (Breathing Lessons). Tyler’s recent books have focused on aging and mortality, with intensely personal and somewhat insular results. Her new novel, A Spool of Blue Thread, widens the parameters considerably to tell a sprawling, multi-generational saga involving many memorable characters. It is, of course, set in Baltimore, and the story revolves around Red and Abby Whitshank—a contractor and social worker, respectively—and their four children. Tyler depicts aspects of everyday family life with sensitivity and nuance, opting for understated resonance and poignant encounters at every turn. The following excerpt reflects the book’s durable charm. Rumors have circulated that A Spool of Blue Thread would be Tyler’s final book, but she assures us there’s another one in the works.

It was a piece of bad luck that one of Abby’s orphans showed up for Sunday dinner. Atta, her name was, and some complicated last name—a recent immigrant in her late fifties or so, overweight and putty-skinned, wearing a heavy, belted dress and stockings that looked like Ace bandages. (It was ninety-two degrees out, and stockings had not been seen in Baltimore for months.) The first anybody knew of her, she was standing outside the front screen door rat-tat-tatting and calling, “Hello? I have come to the right place?”

“Khello” was how she pronounced it, and “have” sounded like “khev.”

“Oh, my goodness!” Abby said. She was descending the stairs behind Stem, both of them carrying stacks of papers they were hoping to find space for in the sunroom. “Atta, isn’t it? Why, how nice to . . .”

She turned to pile her papers on top of Stem’s, and then she opened the screen door for Atta. “I am early?” Atta asked as she clomped in. “I think not. You said twelve-thirty.”

“No, of course not. We’re just . . . This is my son Stem,” Abby said. “Atta’s new to Baltimore, Stem, and she doesn’t know a soul yet. I met her at the supermarket.”

“How do you do,” Stem said. He wasn’t able to shake hands, but he nodded at Atta over his armload of papers. “Excuse me; I’ll just go set these down someplace.”

“Come and have a seat,” Abby told Atta. “Did you have any trouble finding us?”

“Of course not. But you did say twelve-thirty.”

“Yes?” Abby said uncertainly. Maybe the problem was her outfit; she was wearing a sleeveless blouse with a chain of safety pins dangling from the tip of one breast, and wide aqua pants that stopped just below the knee. “We’re pretty informal here,” she said. “We tend not to dress up much. Oh, here’s my husband! Red, this is Atta. She’s come to have Sunday dinner with us.”

“How do you do,” Red said, shaking hands. In his other hand he carried a screwdriver. He’d been fiddling with the cable box again.

“I do not eat red meat,” Atta told him in a loud, flat voice.

“Oh, no?”

“In my own country I eat meat, but here they put hormones.” (“Khormones.”)

“Huh,” Red said.

“Sit down, both of you,” Abby told them, and then, as Stem re-emerged from the sunroom, “Stem, sit down and keep Atta company while I go see to lunch.”

Stem sent her a look of distress, but Abby gave him a brilliant smile and left the room.

In the kitchen, Nora stood at the counter slicing tomatoes. “What am I going to do?” Abby asked her. “We have an unexpected guest for lunch and she doesn’t eat red meat.”

The dinner plates were practically touching, with the silverware bunched between them, and people kept saying, “I’m sorry; is this your glass or mine?”

Without turning, Nora said, “How about some of that tuna salad Douglas got at the grocery?”

“Oh, good idea. Where’s Denny?”

“He’s playing catch with the boys.”

Abby went to the screen door and looked out. In the backyard, Sammy was chasing a missed ball while Denny stood waiting, idly pounding his glove. “Maybe I’ll just let him be,” Abby said, and then she said, “Oh, my,” on a long, sighing breath and went to the fridge for the iced tea.

In the living room, Atta was telling Red and Stem what was wrong with Americans. “They act extremely warm and open,” she said, “extremely hello-Atta-how-are-you, but then, nothing. I have not one friend here.”

“Oh, now,” Red said, “I’m sure you’ll have friends by and by.”

“I think I will not,” she said.

Stem asked, “Will you be joining a church?”

“No.”

“Because Nora, my wife, she belongs to a church, and they’ve got a whole committee just to welcome new arrivals.”

“I will not be joining a church,” Atta said.

A silence fell. Red finally said, “I didn’t quite catch that last bit.”

Stem and Atta looked at him, but neither spoke.

“Here we are!” Abby caroled, breezing in with a tray. She set it on the coffee table. “Who’d like a glass of iced tea?”

“Oh, thanks, hon,” Red said in a heartfelt way.

“Has Atta been telling you about her family? She has the most unusual family.”

“Yes,” Atta said, “my family was exceptional. Everybody envied us.” She plucked a packet of Nutra-Sweet from a bowl and held it close to her eyes, her lips twitching slightly as she read the fine print. She replaced the packet in the bowl. “We came from a distinguished line of scientists on both sides, and we had many intellectual discussions. Other people wished they could be members.”

“Isn’t that unusual?” Abby said, beaming.

Red sank lower in his chair.

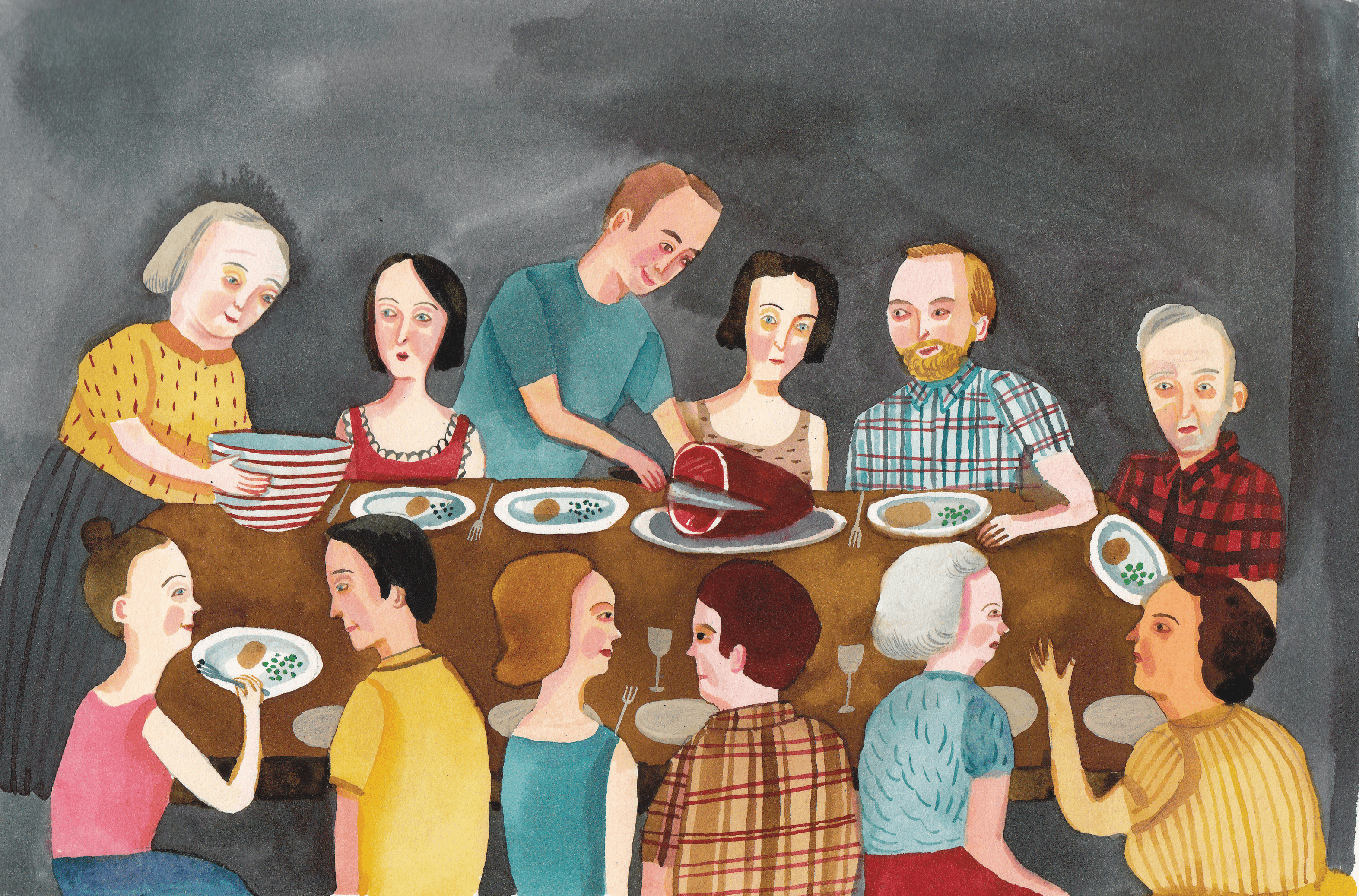

At lunch, there was such a crowd that the grandchildren had to eat in the kitchen—all but Amanda’s Elise, age fourteen, who considered herself an adult. Twelve people sat in the dining room: Red and Abby, their four children and the children’s three spouses, Elise, Atta, and Mrs. Angell, Jeannie’s live-in mother-in-law. The dinner plates were practically touching, with the silverware bunched between them, and people kept saying, “I’m sorry; is this your glass or mine?” Abby, at least, seemed to find the situation exhilarating. “What a multitude!” she told her children. “Isn’t this fun?” They eyed her morosely.

Earlier there had been a little huddle in the kitchen, where most of them had retreated soon after being introduced to Atta. When Abby made the mistake of walking in on them, they drew apart to glare at her. “Mom, how could you?” Amanda asked, and Jeannie said, “I thought you’d promised to stop doing this.”

“Doing what?” Abby asked. “Honestly, if you all can’t show a little hospitality toward a stranger . . .”

“This was supposed to be just family! You’re never satisfied with just family! Aren’t we ever enough for you?”

By now, though, things had settled down to a simmer. Amanda’s Hugh was making his usual production of the carving (he had taken a special course, after which he always insisted on doing the honors), although Red kept muttering, “It’s boneless, for God’s sake; what’s the big deal?” Nora glided in and out of the kitchen, quieting the children and mopping up spills, while Mrs. Angell, a sweet-faced woman with a puff of blue-white hair, did her best to draw Atta into conversation. She inquired about Atta’s work, her native foods, and her country’s healthcare system, but Atta slammed each question to the ground and let it lie there like a dead shuttlecock. “Will you be applying for American citizenship?” Mrs. Angell asked at one point. “Decidedly not,” Atta said.

“Oh.”

“Atta has been finding Americans unfriendly,” Abby told Mrs. Angell.

“My heavens! I never heard that before!”

“Oh, they pretend to be friendly,” Atta said. “My colleagues ask, ‘How are you, Atta?’ They say, ‘Good to see you, Atta.’ But do they invite me home with them? No.”

“That’s shocking.”

“They are, how do you say? Two-faced,” Atta said.

Jeannie leaned across the table to ask Denny, “Remember B. J. Autry?”

Denny said, “Mm-hmm.”

“I just suddenly thought of her; I don’t know why.”

Amanda snickered, and Stem gave a groan. They knew why. (B. J., with her strident voice and her grating laugh, had been one of their mother’s more irksome orphans.) Denny, though, studied Jeannie for a moment without smiling, and then he turned to Atta and said, “I think you’ve made a mistake.”

“Oh?” she said. “’Two-faced’ is an incorrect term?”

“In this situation, yes. ‘Polite’ would more accurate. They’re trying to be polite. They don’t much like you, so they don’t invite you to their homes, but they’re doing their best to be nice to you, and so that’s why they ask how you are and tell you it’s good to see you.”

Abby said, “Oh! Denny!”

“What.”

“And also,” Atta told him, apparently unfazed, “they say, ‘Have a nice weekend, Atta.’ How should I do that? This is what I should ask them.”

“Right,” Denny said. He smiled at his mother. She sat back in her chair and gave a sigh.

“Behold!” Amanda’s Hugh crowed, spearing a slice of beef with his carving fork. “See this, Red?”

“Eh?”

“This slice has your name on it. Observe the paper-thinness.”

“Oh, okay, thank you, Hugh,” Red said.

Amanda’s Hugh was famous in the family for asking, once, why there seemed to be a diploma under the azalea bushes. He’d been referring to the white PVC drainage pipe leading from the basement sump pump. The family never got over it. (“Seen any diplomas out in the shrubbery lately, Hugh?”) They liked him well enough, but they marveled at how astonishingly impractical he was, how out of touch with matters they considered essential. He couldn’t even replace a wall switch! He was trim and model-handsome and accustomed to admiration, and he kept seizing on new careers and then abandoning them in a fit of impatience. Currently, he owned a restaurant called Thanksgiving that served only turkey dinners.

Jeannie’s Hugh, by contrast, was a handyman who worked at the college Jeannie’d gone to. The other girls had had their hearts set on pre-med students, but evidently one look at unassuming Hugh, with his sawdust-colored beard and his tool belt slung low around his hips, had made Jeannie feel instantly at home. Now, here was someone she could relate to! They married during her senior year, causing some discomfort among the college administrators.

At the moment, he was asking Elise all about her ballet, which was considerate of him. (She’d been left out of the conversation up till then.) “Is it on account of ballet that you’re wearing your hair so tight?” he asked, and Elise said, “Yes, Madame O’Leary requires it,” and sat up taller—a reed-thin, ostentatiously poised child—and touched the little doughnut on the tippy-top of her head.

“But what if you were frizzy-haired and couldn’t make it stay in place?” he asked. “Or what if you were one of those people whose hair will only grow so long?”

“No exceptions are made,” Elise told him severely. “We have to have a chignon.”

“Well, shoot!”

“And also these flowing skirts,” Amanda told him. “They tie them on over their leotards. Everyone expects tutus, but tutus are just for performances.”

Abby said, “Oh, Jeannie, remember when Elise was just born and we dressed her in a tutu?”

“Do I!” Jeannie said. She laughed. “She had three of them, remember? We dressed her in one tutu after the other.”

“Oh, they pretend to be friendly . . . but do they invite me home with them? No.”

“Your mom had asked us to babysit,” Abby told Elise. “It was the first time she was leaving you and she felt safer starting with family. So we told her, ‘Go on! Go!’ and the instant she was gone we stripped you down to your diaper and started trying clothes on you. Every single piece of clothing you’d gotten at your baby shower.”

“I never knew that,” Amanda said, while Elise looked pleased and self-conscious.

“Oh, we’d been dying to get our hands on all those cunning outfits. Not just the tutus but a darling little sailor dress and a bikini swimsuit and then—remember, Jeannie?—navy-ticking coveralls with a hammer loop.”

“Of course I remember,” Jeannie said. “I was the one who gave them to her.”

“Well, we were sort of punch-drunk,” Abby explained to Atta. “Elise was the first grandchild.”

“Or else not,” Denny said.

“What, sweetie?”

“You seem to be forgetting that Susan was the first grandchild.”

“Oh! Well, of course. Yes, I just meant the first grandchild who was close; I mean geographically close. I wouldn’t forget Susan for the world!”

“How is Susan?” Jeannie asked.

“She’s good,” Denny said.

He ladled gravy over his meat and passed the tureen to Atta, who squinted into it and passed it on.

“What’s she doing with her summer?” Abby asked.

“She’s in some kind of music program.”

“Music, how nice! Is she musical?”

“I guess she must be.”

“Which instrument?”

“Clarinet?” Denny said. “Clarinet.”

“Oh, I figured maybe French horn.”

“Why would you figure that?”

“Well, you used to play French horn.”

Denny sliced into his meat.

“What’s Susan doing over the summer?” Red asked.

Everyone looked at him.

“Clarinet, Red,” Abby said finally.

“Eh?”

“Clarinet!”

“My grandson in Milwaukee plays the clarinet,” Mrs. Angell said. “It’s hard to listen to him without giggling, though. Every third or fourth note comes out as this terrible squawk.” She turned to Atta and said, “I have thirteen grandchildren, can you believe it? Do you have grandchildren, Atta?”

“How would that be possible?” Atta demanded.

Another silence fell, this one heavy and muffling, like a blanket, and they all turned their attention to the food.

Anne Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread published by Knopf will be available in stores February 10.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Anne Tyler continues the tradition of providing us with an exclusive preview of her new novel. This one, A Spool of Blue Thread, is her 20th—the fifth she’s shared here—and, like her others, is set in her hometown of Baltimore. “It was supposed to be the book that never ended. That’s why I made it an extended family saga, and why it travels backward through time rather than forward,” she says. “I didn’t want to run out of generations, but once I reached 1926, the generations ran out of their own accord; I’d finished it in spite of myself.”