Arts & Culture

AVAM’s New Mega-Exhibit Brings Art and Sports Into the Same Arena

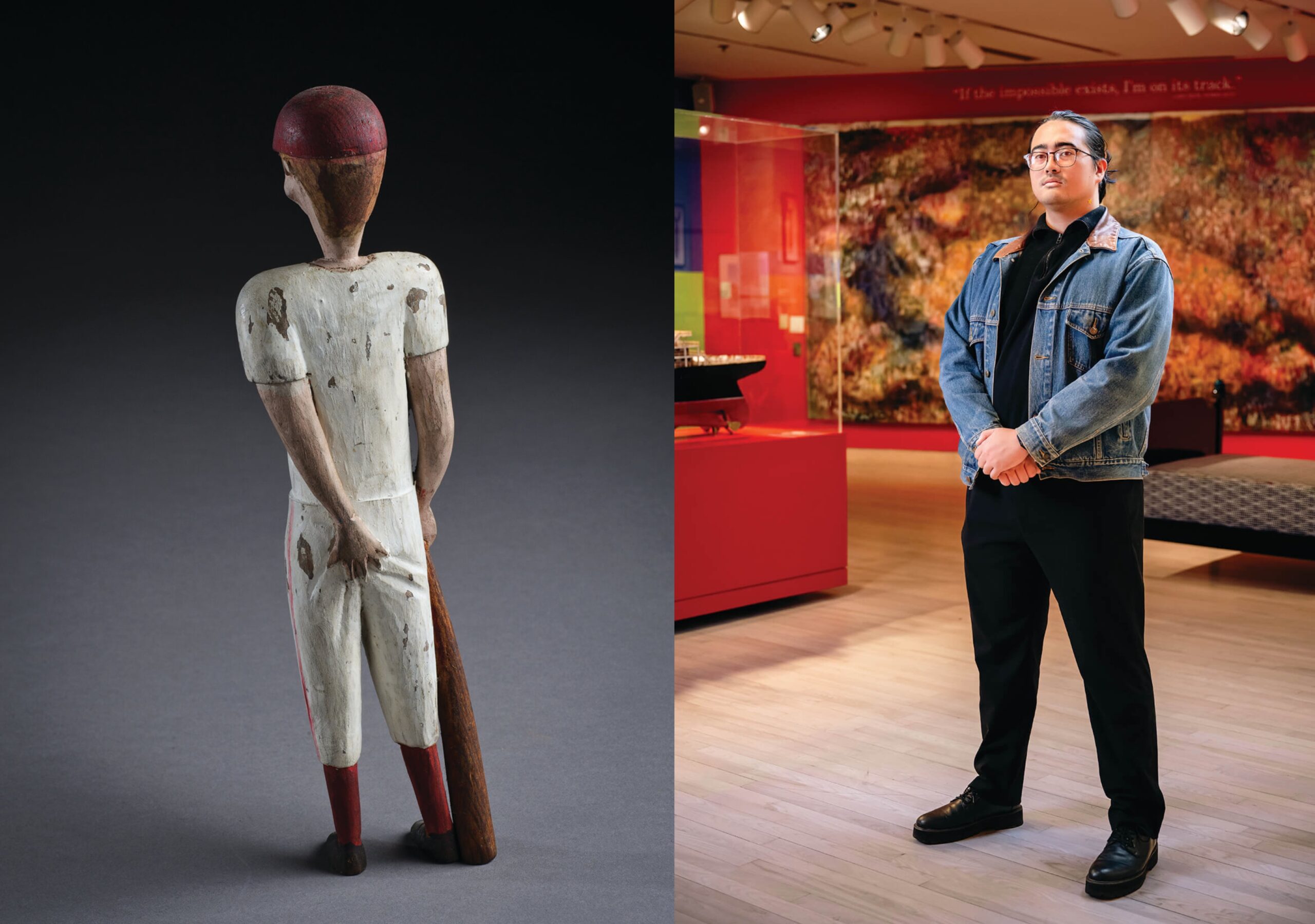

Curator Gage Branda discusses ‘Good Sports,' which focuses on the struggles, values, and plain fun that sports bring to the human experience.

Sports and art generally operate in different arenas, rarely crossing paths on the ball field and court, museum and gallery. So, leave it to Federal Hill’s unconventional

American Visionary Art Museum to mount an exhibit featuring works by a diverse group of visionary artists focused on sports and play, and the struggles, values, and just plain fun they bring to the human experience.

Curated by Maryland Institute College of Art graduate Gage Branda, the wide-ranging Good Sports: The Wisdom & Fun of Fair Play covers sports and competitions from baseball, basketball, and boxing, to old-school pinball. The various mediums include painting, photography, sculpture, linocuts, mixed-media works, artifacts, oral histories, and a diorama of a historical soccer match, whirligigs of runners, and a visual homage to Mexico’s lucha libre professional wrestling.

It’s not all whimsy, however. Included are stories of social justice, childhood, camaraderie, and even religious transcendence.

The opening night party included sports-themed music—John Fogerty’s “Centerfield” to name one—and guests dressed in ball caps, jerseys, and warm-up suits. Definitely out of the ordinary for a major art opening. What was the spark for this show?

This exhibition came from a series of conversations we had within the museum. What began to resonate was a feeling of perceived division in the country, which stands in contrast to ideals around sportsmanship, which values treating each other with respect and dignity and winning and losing with grace. We’d like to believe that there are conflicts in our lives and in the world around us that could be resolved if we viewed our perceived rivals or adversaries in the same way that someone views a rival or adversary on the field. We saw it as a good opportunity to take some of that wisdom from athletes who push themselves to be their very best, but also display grace and civility.

One of the panels that stuck with me included an explanation of the English word “compete.”

It is derived from the Latin verb competere, which means to strive together, to meet, to come together, agree. It puts the focus on the camaraderie of competition. Yes, in Latin, it’s not antagonistic; it means to strive together. So, we reframed it, which was a brilliant idea from [AVAM founder] Rebecca Hoffberger. It’s her practice to look at words and examine their meaning as they were coming into the language, and what they mean today. I agree. It changes the context, the nature, of competition.

Did you play sports? Or, given your degree in sculpture, did making art always come first?

I played a little bit of sports growing up. I liked skateboarding a lot. There are competitions in skateboarding but, for me, it was always about, “How can I be better next time than I was this time?” When you look at the story of Roger Bannister, for example, the first person to run a sub 4-minute mile, he was only thinking about how he could get faster. In that way, athletes and artists do share something in common—the way they work at their craft, their “practice.”

I love the whimsy in the show, like Tom Wilborn’s carved piece of the baseball player in the on-deck circle scratching his rear end. We don’t necessarily associate whimsy with sports.

I tried to concentrate on artworks that weren’t about the spectacle of sport, but pieces that were more personal. It’s not a sculpture of Babe Ruth. But if you played or if you’ve watched baseball, if you watch your kids play baseball, you’ve seen this. I played some baseball and there are moments when you daydream and chew on gum or the grass you pulled up in the outfield because you’re bored. It’s one of those moments.

I also love William Wells’ memories of playing in Baltimore’s James Mosher League, the oldest continuously operating African-American youth baseball league in the country.

He tells a charming story about how he didn’t get a hit his first or second season but had a lot of fun. He learned about what it means to be on a team, what it means to cheer for your friends, what it means to care about each other, and just to have good mentors and leadership around you. I thought it could pertain to any social group, but it’s especially the kind of thing that youth sports, at their best, are all about.