Arts & Culture

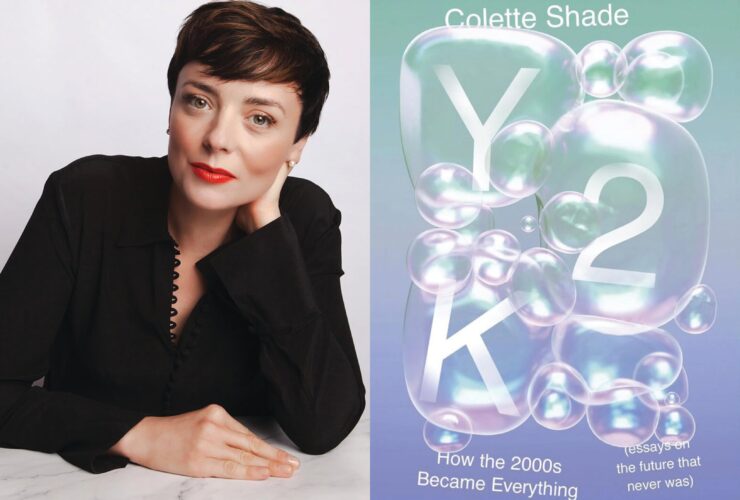

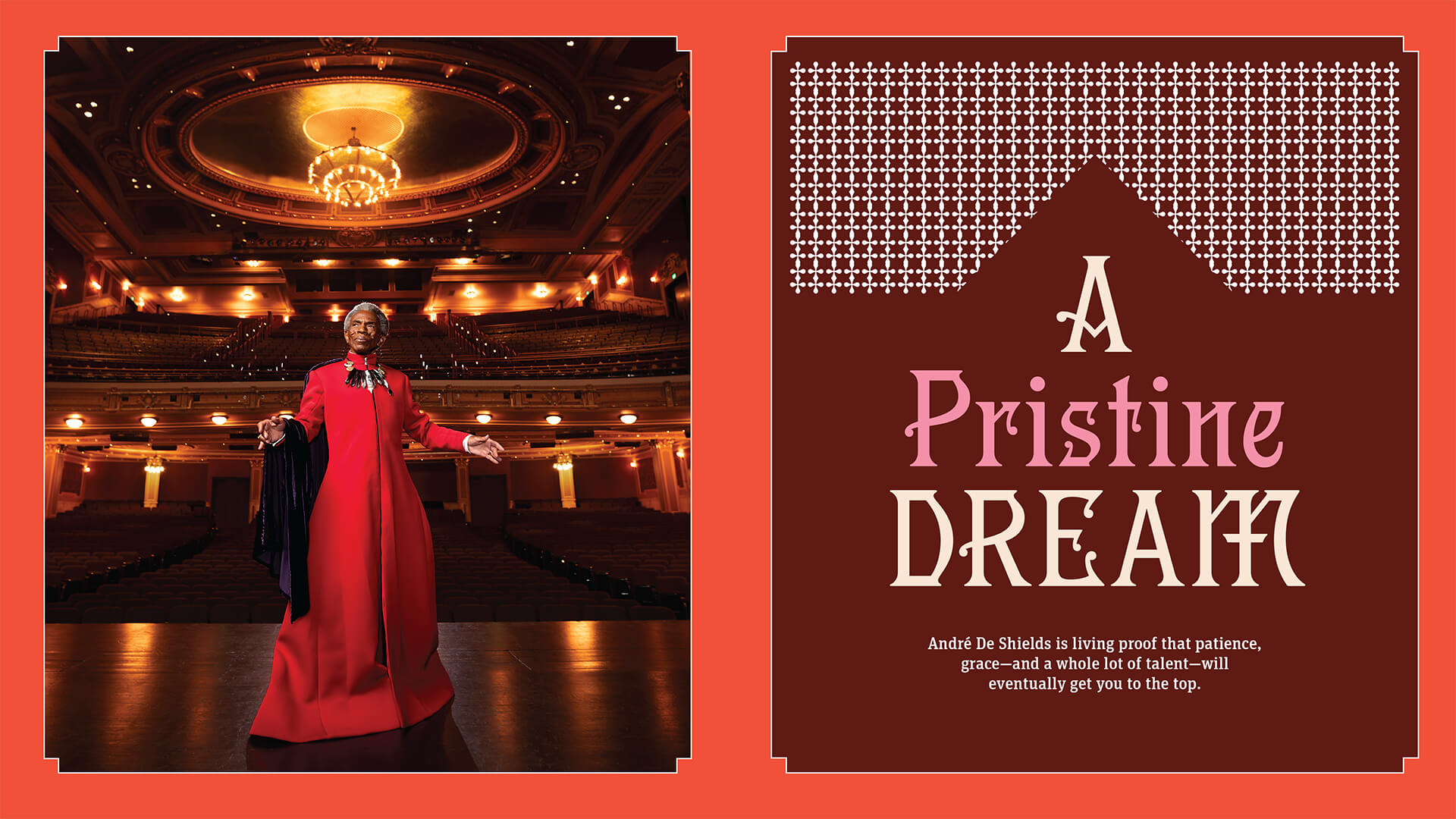

A Pristine Dream

André De Shields is living proof that patience, grace—and a whole lot of talent—will eventually get you to the top.

By Lawrence Burney

Photography by Mike Morgan

round this time last year, the 1800 block of Division Street in the city’s Upton neighborhood looked a little different than it would on a regular day. For one, the street was blocked off, which would typically be a significant inconvenience for Westside residents trying to cheat the steady traffic flow going up and down Pennsylvania Avenue. Secondly, there was a podium set up in the middle of the street, prepped for city officials like Mayor Brandon Scott and City Council President Nick Mosby to speak.

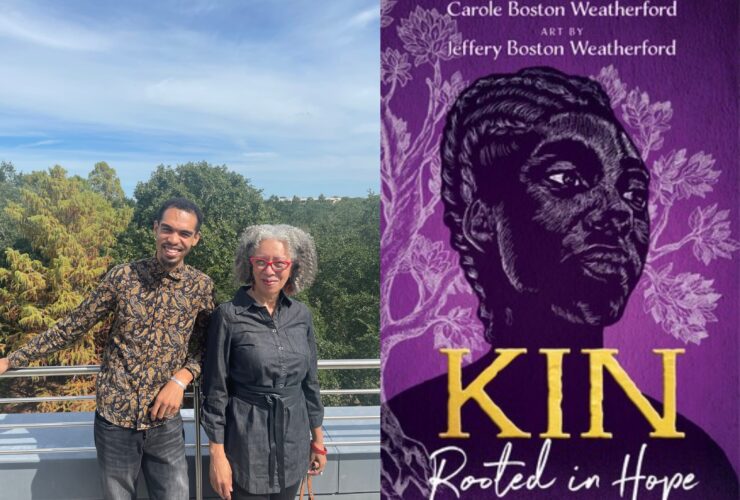

In Baltimore, scenes like this, unfortunately, are often associated with responses to tragedy in which politicians show up to assure folks of how they’ll do everything in their power to guide the city to a place of healing and restoration. But luckily, on this day, all of the commotion—students dancing, news cameras everywhere, and community members passing by—was in celebration of André De Shields, the 78-year-old theater virtuoso whose formative years were spent on this very street, which was now being named after him.

“I always want to create opportunities to celebrate individuals while they are still here, to feel the love we have for them, and that’s what brings us all here: sharing the love, respect, and admiration we have for Mr. André De Shields and all that he has done to represent Baltimore and make us proud on the world stage,” Mayor Scott told the crowd. “He is many, many things: an artist, activist, philanthropist, Broadway deity, culture connoisseur, and one of the best dressed men on the planet.”

It’s true. Dressed in a perfectly tailored maroon suit, accented by a baby-pink shirt and socks, with a masterfully manicured short gray Afro, De Shields let out a thunderous laugh at the compliment. Throughout the ceremony, the man of honor sat perched up in a folding chair behind the podium, gleefully taking in kind words from fellow Baltimoreans.

“To know him is to love him, because he is mesmerizing and just everything,” says Tonya Miller Hall, the city’s senior advisor for the Office of Arts & Culture, who was in the crowd that day. “He’s a big deal, a legend.”

Many people’s first knowledge of De Shields—including my own—came only a few years ago, when, in 2019, he won Best Featured Actor in a Musical at the Tony Awards for his role in the Broadway musical Hadestown. But more than the honor itself, it was his speech that captivated people watching in all corners of the world, especially ones on the journey of achieving their own creative pursuits in a world that seems to prioritize those who can make the biggest splash in the shortest span of time.

But as he stood in front of the mic on Division Street last September, his head to the sky, De Shields offered a handful of equally razor-sharp mantras to sit with: “Surround yourself with people whose eyes light up when they see you coming.” “Slowly is the fastest way to get where you want to be.” “The top of one mountain is the bottom of the next—so keep climbing.” But before he got there, the first words he uttered—yelled, really—when stepping on the stage were “Baltimore, Maryland!” Then, continuing, “I hope you’re watching at home, because I am making good on my promise that I would come to New York and become someone you’d be proud to call your native son.”

The speech spread far and wide the second it hit social media, as it was a testament to the power of persistence, perseverance, and a lifelong dedication to one’s calling—the kind of moment that can achieve evergreen status, as its relevance is infinite. What was most evident from the speech, though, was that De Shields readied himself for it long before his name was called.

“There was never a time that I didn’t know what I was going to be as an adult,” De Shields said over the phone back in July, quick to check me when I asked him to recall the particular moment he knew he was meant for the stage. “That’s important to note, because many people spend all of their childhood, adolescence, and young adult lives wondering, ‘What is my purpose? What is my direction?’ Well, I knew. I knew that my eye was on the prize.”

Opening Spread: ON THE HIPPODROME STAGE IN BALTIMORE THIS PAST JULY. —PHOTOGRAPHY BY MIKE MORGAN. GROOMING BY BRIAN OLIVER, T.H.E. ARTIST AGENCY. WARDROBE BY DEDE AYITE (RED CLOAK) AND QUEEN JEAN (PURPLE CAPE). STYLING BY ZINDA WILLIAMS.

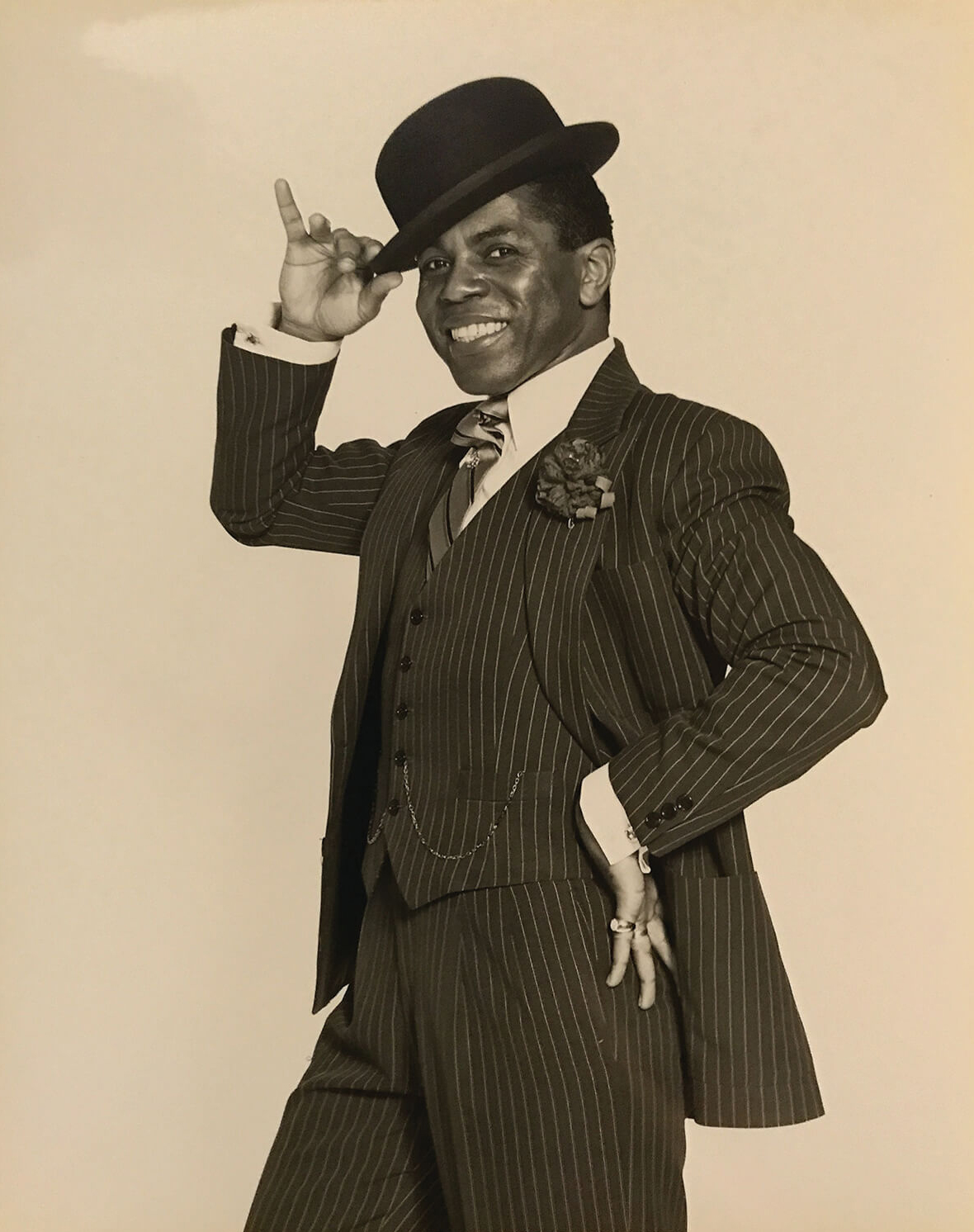

A promo photo for

Ain't Misbehavin',

circa 1978. —COURTESY OF AGENCE FRANCE/MATTHEW MURPHY AND EVAN ZIMMERMAN

The prize, some seven decades ago, was to be like Sammy Davis Jr., an “entertainer extraordinaire,” as De Shields puts it. Davis Jr., at that time, was the most accessible image of the Black American superstar. Although De Shields was born in Dundalk—the ninth of 11 children—his father, a tailor, moved the whole family to Upton when André was just five. And in the Upton of the 1950s, larger-than-life entertainers weren’t just on the silver screen or radio broadcast, they were around the corner. Back in those days, just one block west of Division Street was a Pennsylvania Avenue that sounds more like myth than reality to anyone born after the ’60s.

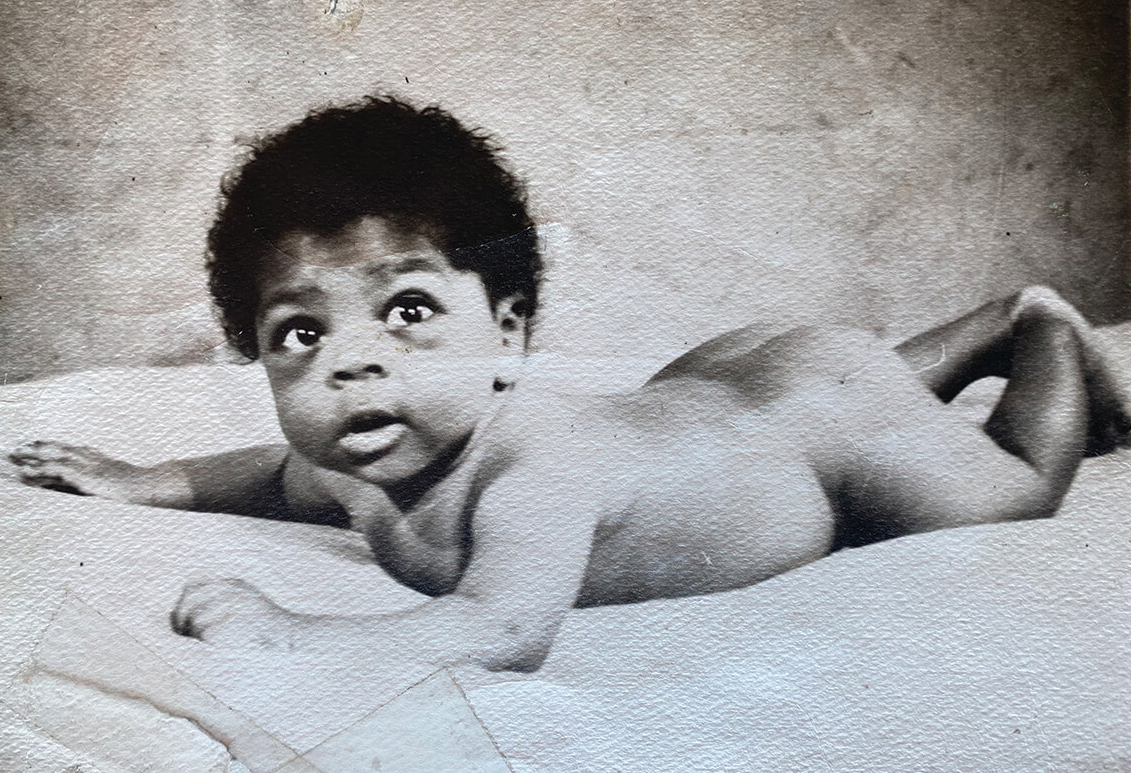

Baby André. —Courtesy of Lia Chang

De Shields’ childhood was spent frolicking up and down The Avenue when The Royal was still open, when comedic superstar Red Foxx had a nightclub on the strip, and when it wasn’t uncommon to see Black stars like Duke Ellington or Etta James strolling down the street while they were in town for gigs. “It’s where we would get our entertainment, our social education—it’s where I saw my first Motown revue,” remembers De Shields fondly.

In some ways, De Shields picked up on his parents’ dreams. In a Baltimore Sun profile of him from 1993, his sister, Mary, shared that their father was a singer who, on occasion, performed with a local group called the Elite Singers. Their mother had aspirations of being a dancer. So when a young De Shields wanted to participate in grade school pageants, he received support from parents who knew what it felt like to have creative inclinations.

The event that sealed his destiny, he says, came when he was nine years old, in 1954. He went to The Royal to see the 1943 film Cabin in the Sky, which starred some of the most prominent Black stars of the time: Ethel Waters, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Rex Ingram. The film was also an adaptation of a popular Broadway show, foreshadowing De Shields’ future career.

One scene in particular captivated him, cementing his desire to entertain. It was when the musical duo Buck and Bubbles performed a routine in which Buck played the piano and Bubbles took the floor, singing a tune about how women liked his pearly-toothed smile, and proceeded to hit a medley of light-footed Black dance moves of the early 20th century. He practically floated. “Each of us has this voice in us that speaks to us quietly—it doesn’t shout, but it also doesn’t lie,” says De Shields, remembering his first time witnessing it. “When I saw him in this film doing this unbelievably smooth routine, that voice said to me, ‘André, that’s what you are going to do.’”

He carried that internal voice with him, but largely decided to keep his aspirations to himself. “If one is living in a segregated city and is impoverished, the surest way to achieve your goal is to keep your dream close to your chest,” he says. “Because if you share it, then they’ll say, ‘Oh, you just a crazy nigga.’ If you expose your dream to that kind of conversation, just as if you pick cotton long enough, you believe that you are afraid. So you have to keep that dream pristine in your heart. But, at the same time, you use those people who would disparage you as life lessons. You don’t know me. You can’t advise me. I’m not going where you are headed.”

As King Louie in

The Jungle Book, 2013. —Courtesy of Lia Chang

In costume as The Wiz, 1975. —Courtesy of Lia Chang/Martha Swope

While his 10 siblings went on to high schools like Douglass and Carver, De Shields set his eyes on Baltimore City College, which, at that time, was a prestigious institution with only male students and very few Black ones. From there, he went on to Wilmington College in Ohio, where he starred in a production of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, before transferring to the University of Wisconsin and eventually finding his way on the musical cast of Hair in Chicago. Soon, he would land the title role of The Wiz in New York City—a moment that would set the track for a legendary career that hasn’t come to a pause since.

When The Wiz comes to mind, many think solely of the Michael Jackson and Diana Ross-starring feature film from 1978. But the cult classic piece of cinema was adapted from the 1974 Broadway show of the same name, in which De Shields played the original wizard. And when it debuted—in Baltimore, no less, at the now-closed Morris A. Mechanic Theatre on South Charles Street—it was larger than life.

“In addition to the Civil Rights Movement, entertainment was a house of healing,” says De Shields. “People go to the theater to have questions answered. I mean, the audiences might not articulate it this way, but if you don’t answer a question, if you don’t resolve a crisis, if you don’t lift the burden, they’ll let you know.”

Maybe what De Shields meant was that, coming out of a transformative yet turbulent decade like the ’60s, Black Americans were in need of entertainment that transported them—that helped them dream of a world in which they were the orchestrators and conductors, navigating a rugged terrain with shady characters and unexpected twists at every corner—and doing it together.

If so, The Wiz succeeded in that regard. “We knew that we were doing something magical and something miraculous because it brought Black audiences to the Great White Way, which had been an inhospitable terrain for 200 years prior to that,” he says, noting that during his childhood, he was unable to attend performances at the Hippodrome, then a segregated theater. “There would be no Broadway if it had not been appropriated from the natural talents of the Black people who were enslaved here and who thrive and survive and now are prevailing through their natural ability to forgive those who do them wrong.”

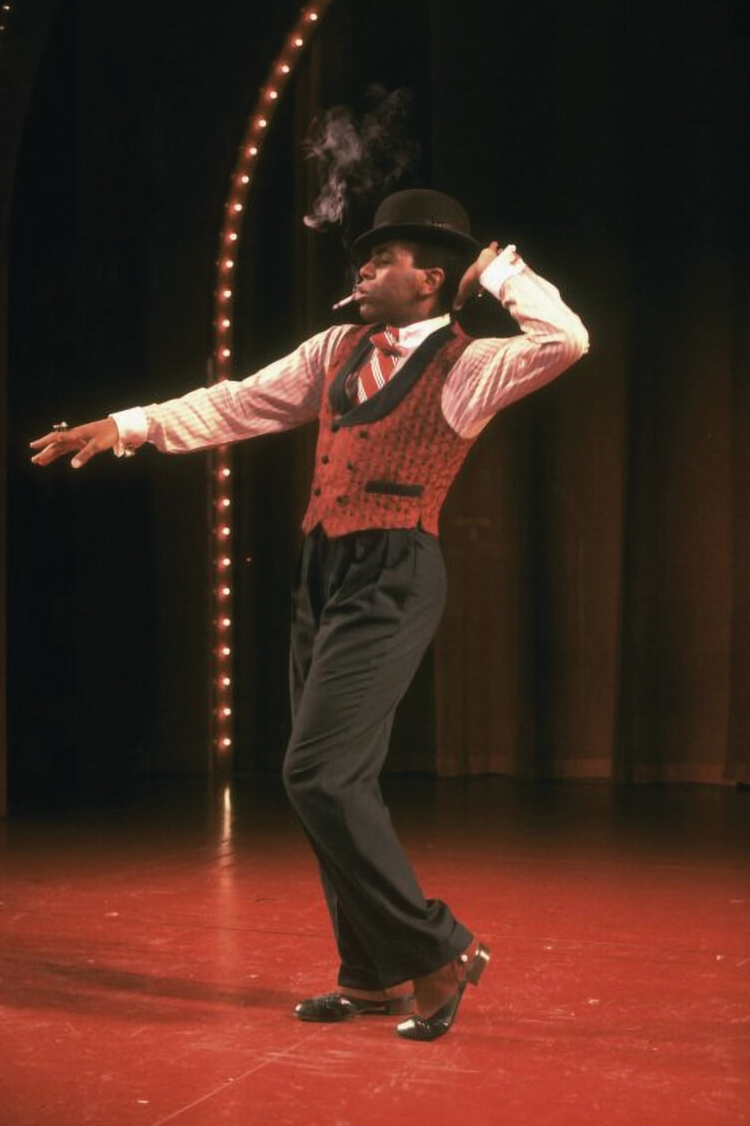

Performing in Ain't Misbehavin', 1978. —Courtesy of Lia Chang/Martha Swope

Decades later, in the early 1990s, De Shields was making his big return to his hometown as The Wiz was gearing up for revival shows across the country, this time at The Lyric. By that time, he was an established theater standout, with decades-spanning key roles in productions like Ain’t Misbehavin’ and Stardust. He was unsure about how relevant this show could be in this new era—that is, until the Los Angeles Police Department’s brutal beating of Rodney King in 1992 was televised, sparking widespread uprisings out west. It brought him back to the play’s necessity in the ’70s. The revival was also timely for his own healing. That same year, his life partner of 17 years, the playwright Chico Kasinoir, died of complications from HIV. “ When Chico died in June,” he told The Sun in that 1993 story, “I would have had nothing to do in July—when The Wiz started rehearsing—except luxuriate in my misery, instead of using all that energy on a character that ultimately gave me an opportunity to give vent to all of that rage.”

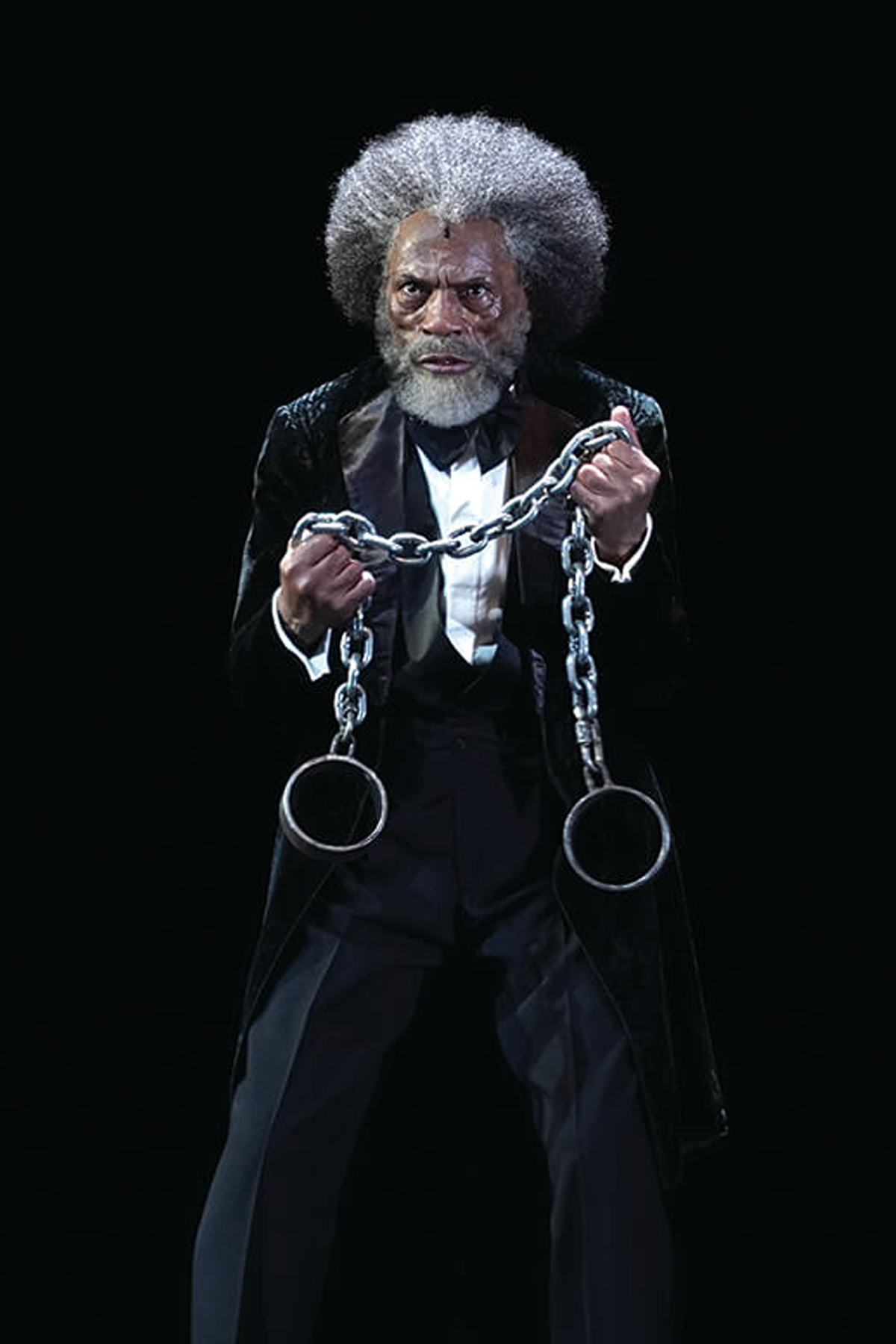

De Shields

as Hermes in Hadestown,

2019; as

Frederick Douglass, 2021. —COURTESY OF LIA CHANG

Arts & Culture

Fall Arts Preview: Can’t-Miss Cultural Events to Experience in Baltimore This Season

Over the next few months, brand-new seasons of cultural programming begin again at venues all across the city—bringing with them fresh exhibitions, plays, performances, and much more.

Whether he knew it or not, at that time, De Shields was also coming out of a dry spell in terms of his theater career. After The Wiz’s revival, he experienced a career revival of his own. In 1997, he was cast as Jester in Play On!, the musical adaptation of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. And then, in 2000, as Horse in the Broadway adaptation of The Full Monty. Then, in 2019, he was cast in the role that changed his life: Hermes in Hadestown. He brought all of his insinuating elegance and charisma to the role and it came as a surprise to no one when he won that Tony.

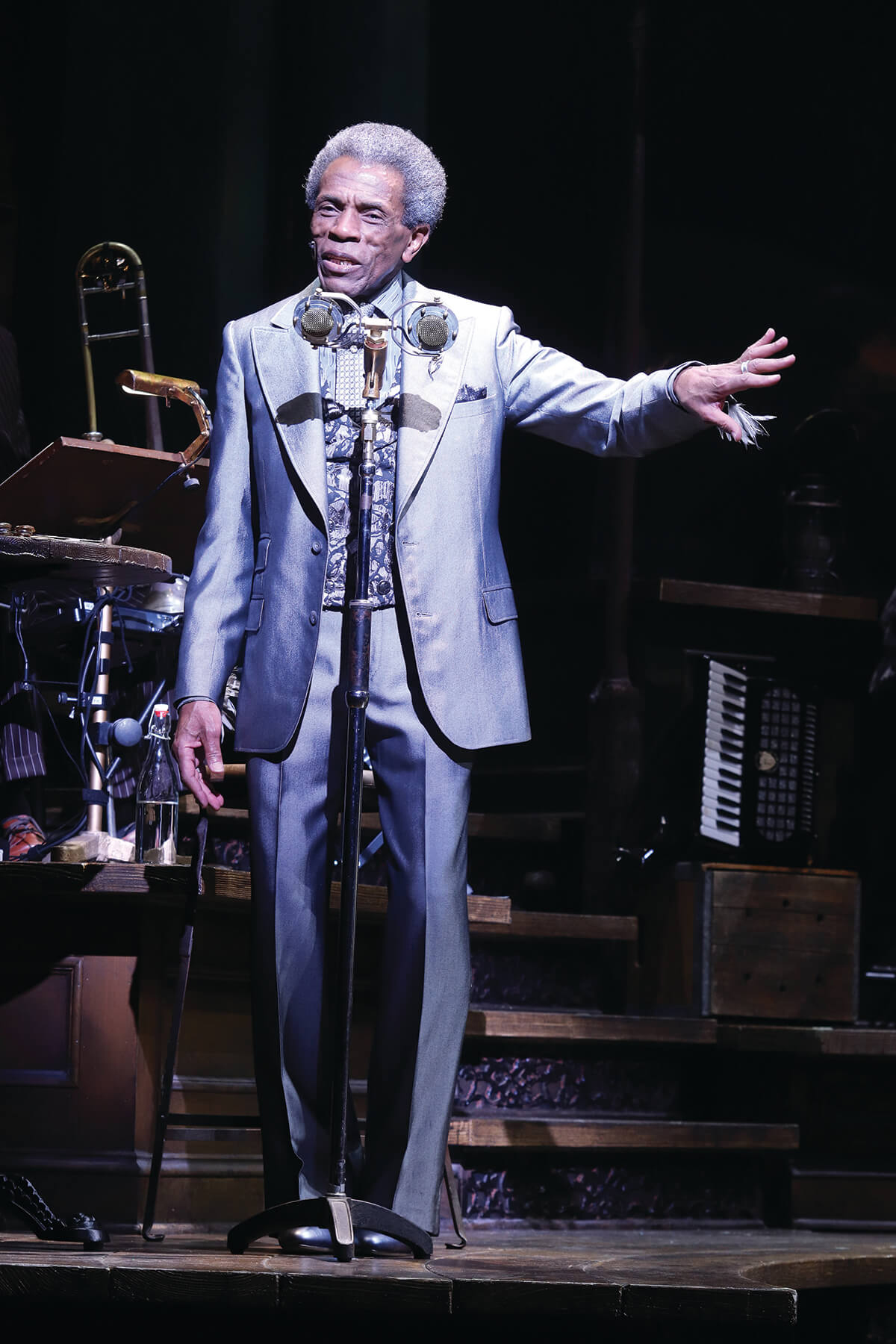

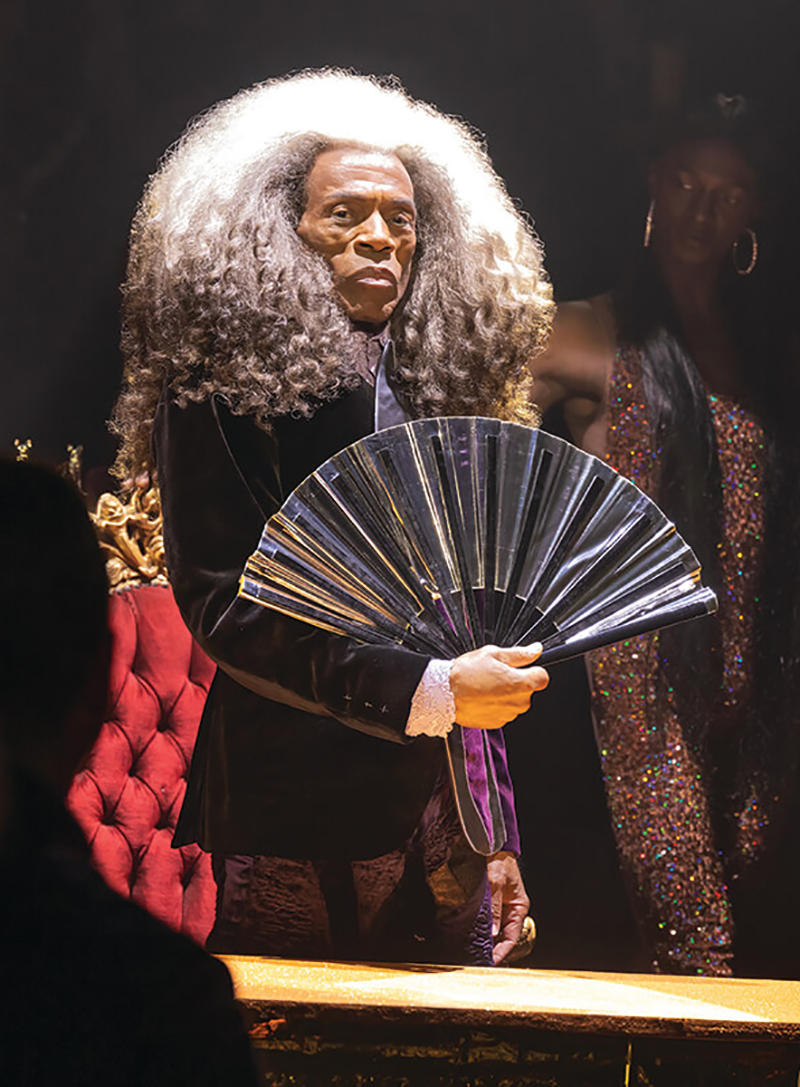

Currently, De Shields is making his rounds as Old Deuteronomy in a new rendition of Cats, which draws heavily from drag culture and New York City’s decades-long queer ballroom scene.

De Shields in costume as Old Deuteronomy in Cats. —COURTESY OF MATTHEW MURPHY AND EVAN ZIMMERMAN.

On a late July evening at the Perelman Performing Arts Center in Lower Manhattan, about a quarter into the show, the lights went completely dark, long enough for De Shields to appear on stage adorned in a purple suit and a flowing, shoulder-length gray wig, staring out into the audience as if he owned the place. When his face was revealed, the crowd let out a resounding scream in unison, just before he raised his hand to flex his supernatural powers over his fellow cats, who all fell to the ground when he pointed toward them. His command over the space was a pure joy.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of except yourself, that’s what Cats is about,” he says. “And that is why the LGBTQ+ community are the ones who are now teaching the lessons, because they have been on the outside of the circle of life for so long, and everybody else is throwing up their hands and thinking the only way to achieve anything is to kill. That’s the exact opposite; killing only brings death. And what we want to do is promote life.”

It’s nothing short of awe-inspiring that De Shields still has the passion, at nearly 80, to continue on with his calling of being an entertainer extraordinaire, just like his adolescent hero, Sammy Davis Jr.

“He’s not only a Broadway legend—just really one of the industry’s most talented performers, singers, actors, choreographers, directors—but he’s a legend in Baltimore,” says Ron Legler, president of the Hippodrome, who saw the original production of The Full Monty. “They named a street after him, and it’s funny, because it’s called Division. If anything, André brings people together.”

Joyously celebrating on André De Shields

Way, photographed this past July. —PHOTOGRAPHY BY MIKE MORGAN.

GROOMING BY BRIAN OLIVER, T.H.E. ARTIST AGENCY. STYLING BY ZINDA WILLIAMS.

A lifelong career in the arts isn’t for the faint of heart, but, according to him, the 410 prepared him for this journey. Though he lives in New York full-time, he comes home often enough, for performances at the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, or to receive the official “keys to the city,” like he did back in 2019, or to help promote Artscape, like he did last year.

“When people speak of the Big Apple, they say if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere—that’s true,” he says. “But if I hadn’t first made it in Baltimore, I never would’ve made it in New York. It’s where the seeds of that radical courage were planted.”