Arts & Culture

Inside Annie Howe Papercuts’ Lauraville Studio

With just a knife and a pencil, artist Annie Howe turns pieces of paper into intricate works of art.

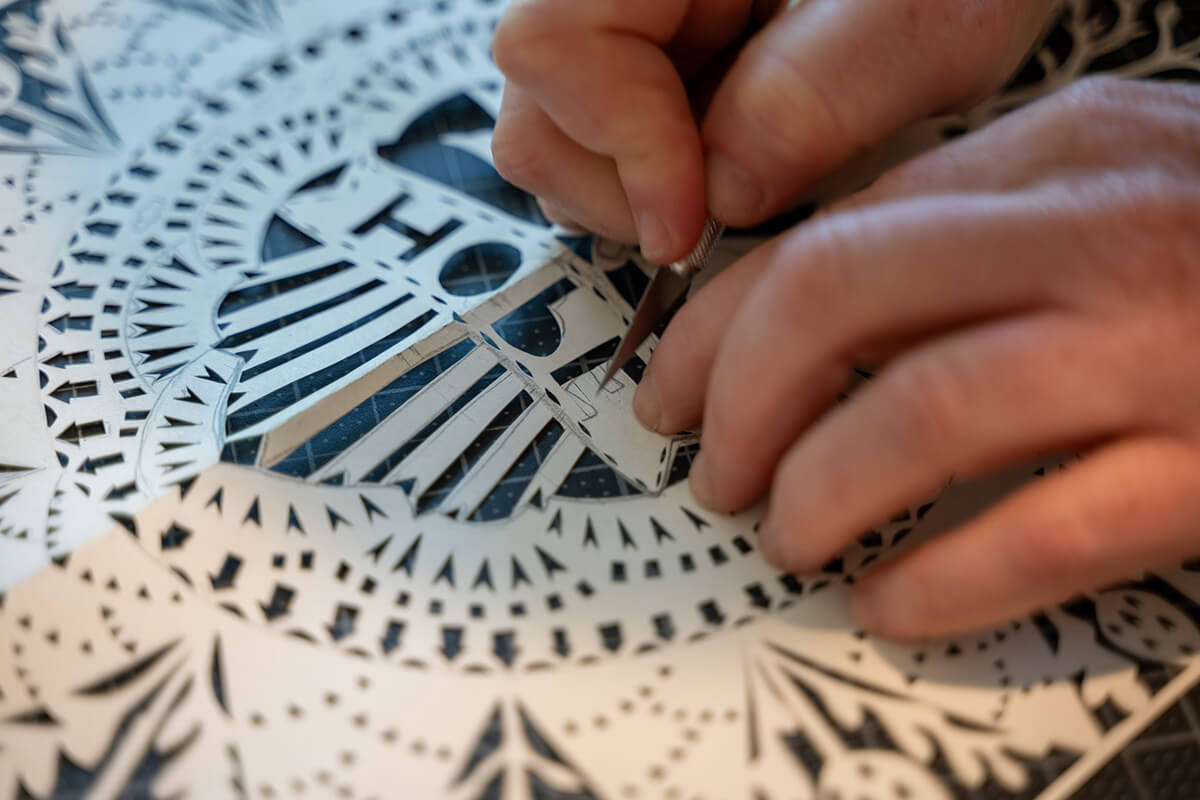

Annie Howe sits at her table, X-Acto knife in hand, working meticulously as little shards of discarded paper scatter around her like confetti. Her cuts are quick, controlled, and accurate—it’s like watching a skilled surgeon—and within a few seconds she’s created a beautiful border around a quickly sketched tree as she demonstrates her papercut technique.

A gallon Mason jar full of razor blades sits on her desk a few inches away from where she works in her sun-filled studio in Lauraville.

“I wanted to do one of those things where you’re like, ‘Guess how many jelly beans are in the jar,’” she says with a laugh in her distinctive voice—a mix of her Rhode Island upbringing and her 27 years in Baltimore. Today, she’s wearing a cat apron, the bow neatly tied at her waist, her arms freckled exactly like you would expect from a strawberry blonde like her. She nods to the jar. “I mean, this is probably years and years, but it’s like that because the blades are so small.”

Those little blades have made a big impact.

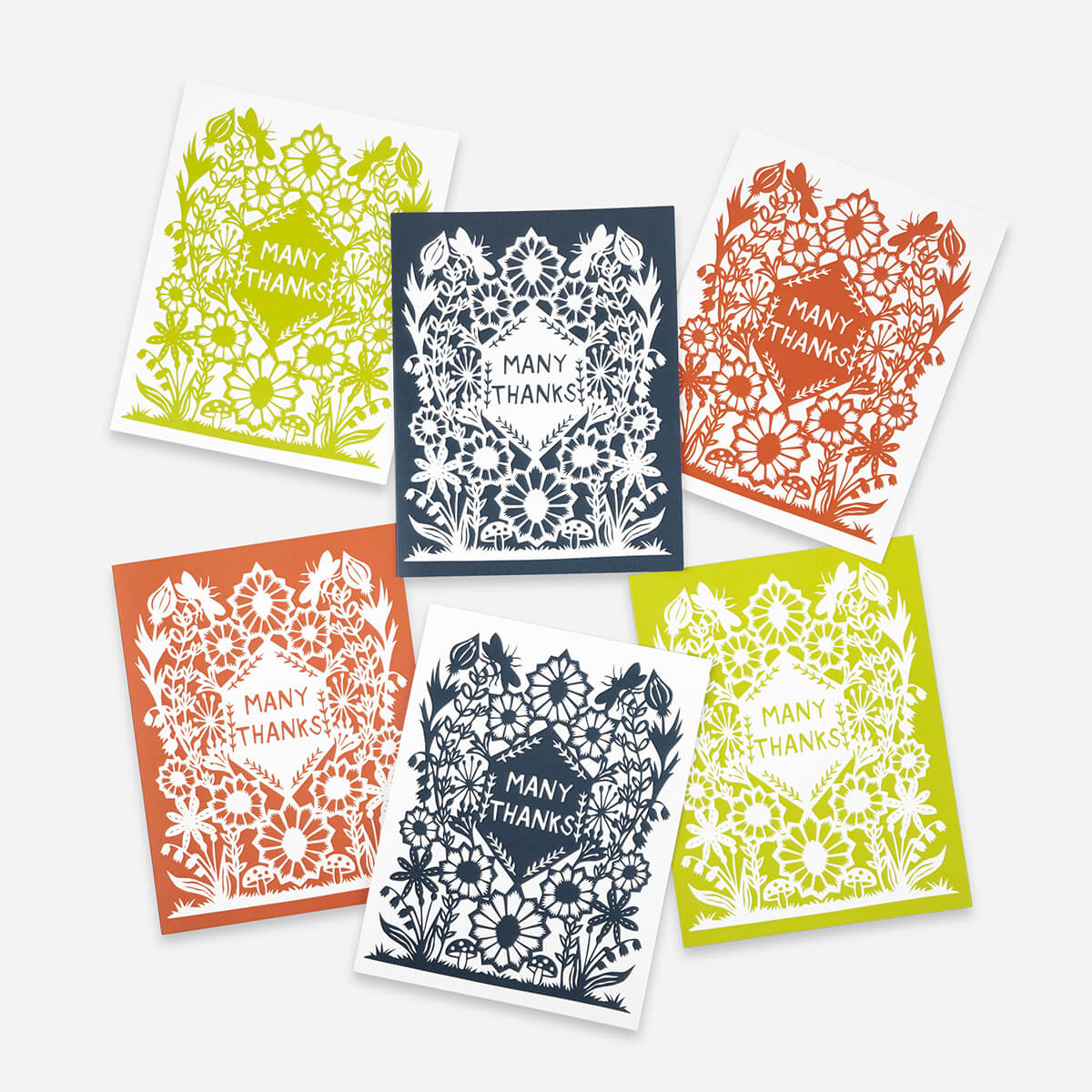

A year ago, Howe moved into a new studio upstairs at Found Studio Shop to accommodate all the work she’s doing. Her papercuts are sold downstairs, at Mount Royal Soaps, and on her website, and her work has adorned everything from Eddie’s of Roland Park grocery bags to gift tags sold by Anthropologie.

Her needs for papercutting are simple—a pencil (she prefers Ticonderoga), 70-weight paper, an eraser, a pencil sharpener, her cutting knife, and always Excel branded blades. It starts with a sketch in pencil on the paper—and then she gets to work.

“I tell people in my workshops—this is the way I do papercutting. I don’t know if this is the way everybody else does it,” says Howe. “That’s the thing I love about papercutting, there’s really no right or wrong way to do it. There are no right or wrong materials to use. It’s highly up to you, which is so cool.”

Her pieces are complex, playful, and stunning and often involve woodland creatures, florals, or familiar cityscapes. She can expertly add words that seem to be hanging by a thread—and the fact that all her sketching is done backwards on the back of the page makes it all the more mind-blowing.

“I didn’t realize, when I got into it, the depth and history of papercutting as an art form,” admits Howe.

Papercut art first appeared during the Jin dynasty in 4th century C.E., after Chinese official Cai Lun invented paper in 105 C.E. Papercutting continued to be practiced during the Song and Tang dynasties as a popular form of decorative art. By the eighth or ninth century, papercutting appeared in West Asia and, in the 16th century, Switzerland and Germany established scherenschnitte (“scissor cutting”).

According to the Guild of American Papercutters, located three hours outside of Baltimore in Somerset, Pennsylvania, the “Pennsylvania Germans brought the art of scherenschnitte to America in the 1700s and used the cut work to decorate birth, baptismal, and marriage certificates.”

Howe came into papercutting in kind of a circuitous way. She grew up in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, before moving to Providence as a teenager when her mom got a job in Boston. “I have always loved art from the beginning,” says Howe.

That was solidified when she ended up at a high school with a strong art program that included continuing education classes at the nearby famed Rhode Island School of Design. She knew she wanted to study art in college, but also wanted to get out of Rhode Island—so she headed to the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). The first time she stepped foot in Baltimore, she was completely smitten.

“I was totally charmed by the architecture of Bolton Hill,” says Howe. “Baltimore seemed really cool.”

Her plan was to be a painting major, but she felt she was “not as talented as many of the other painters”—so she switched to fibers and quickly found her niche.

“I think I was drawn to printmaking and fibers because what I really liked was the processes of doing things,” she says. “I liked fabric dyeing, silk screening—the technique, the physical nature, and the repetitive tasks, which papercutting is sort of in a way too.”

Howe became involved in performance art, including costume and mask making and puppetry. That all came to fruition when MICA’s community art partnership paired Howe with an after-school art program and she, alongside fellow student Kate Cusack, was tasked with creating a big spring festival in Bolton Hill with the kids.

“That was really an exciting experience, because I was like, ‘Oh, this is a way that I can use my interest in giant puppets and street parade and fiber arts and organizing.’”

She also spent summers interning with performance group Big Nazo back home in Providence, where she crafted puppets, did street theater, and was even able to join the troupe on a trip to Scotland. “I always like to be part of a team, which is funny, because now I work mostly on my own; but I’ve always loved collaborations.”

After Howe graduated in 2001, she spent a few years teaching art after school at the Chesapeake Center for Youth Development in Brooklyn and South Baltimore. She was introduced to Molly Ross at a lantern-making workshop. Ross was the director of Nana Projects, a group consisting of self-proclaimed visual alchemists and lanteeners, who were responsible for the design and production of the Creative Alliance’s Great Halloween Lantern Parade.

“I was looking to hire staff for the next Lantern Parade, and she seemed perfect,” remembers Ross. Part of Howe’s job was creating miniature shadow puppets that would be shown on overhead projectors for the finale of the Halloween parade. Howe took the technique and supersized it. “She cut these large-scale papercuts to be decorations for a fundraiser we were having,” says Ross. “And they turned out to be gorgeous.”

Everything about it felt instantly innate to Howe. “I think it came really naturally, and that’s part of the reason why I gravitated to it,” she says.

She started experimenting with different techniques. “I would fold the paper in half—I still mostly do that—fold, draw, and cut what I can,” she says. “That is just part of the fun of it; it’s always a little unpredictable. You never know exactly how it’s going to turn out.”

“THAT IS JUST PART OF THE FUN OF IT…YOU NEVER KNOW EXACTLY HOW IT’S GOING TO TURN OUT.”

For Christmas that year she made paper-cuts for her family. “I think they were like, ‘Okay, that’s cool, I guess. I don’t know, a little weird,’” she says, laughing. Up until that point, it was still just a part-time job and hobby. And then in 2008, Howe’s friends Winston Blick and Cristin Dadant opened the restaurant Clementine in Hamilton and needed artwork for the walls. “I was making a lot of veggie-themed work [for them] and Winston told me I needed some meat.”

Customers loved them. “And that’s part of the thing about Baltimore,” says Howe. “Just from day one I felt like people were so encouraging.”

That included the now-closed Trohv (then Red Tree), which became Howe’s first retail shop. “I emailed them, and they helped me figure out prices and presentation. I just didn’t know any of that stuff.” (In a full-circle moment, she created a stunning full window display for their 10th anniversary in 2016.)

“When we first met Annie, I was stunned by her ability to portray a story with such precision, scale, and with such a kind and visionary spirit,” says Trohv owner Carmen Brock.

Buoyed by the exposure, Howe began doing the craft show circuit and Woodberry Kitchen approached her about creating a T- shirt for their staff. That was her lightbulb moment. “I realized this is something I could do for other people.”

At that time, through a MICA AmeriCorps program, she was working full-time at Nana Projects while also doing more and more papercutting, including commissions. When Nana Projects ended after Ross moved to Florida, Howe took a somewhat mundane part-time sales job with a produce distributor, and soon realized that what she was making there she could easily earn if she dedicated herself to papercutting full-time.

It didn’t hurt that she had some safety nets in place. “I was married at the time. We had a house. I could do my artwork in the basement. I wasn’t totally just going out on my own, so I said, ‘Let me see if I can do this.’”

That was 2012, and she hasn’t stopped creating. That includes partnering with other artists and businesses to make products such as book covers, window displays, ornaments, public artwork, posters—even a “Welcome to Mathias” billboard for a town in West Virginia.

“Annie is one of those artists who is a retailer’s dream—she is focused, creative, fun, open-minded, and thoughtful,” says Brock. “Without a doubt, she played a formative and important role in Trohv’s history and expression of notable artwork.”

Ross says a few years ago she was in an Anthropologie store and saw an advent calendar that looked like Howe’s style. “I picked it up, and it was indeed her work.”

Her collaborative work continues to grow as she finds new ways to take her art to the public, including as Ladew Gardens’ artist-in-residence this past September.

“Annie’s work is so elegant and joyful, and she has been hugely popular with the Ladew community,” says Emily Emerick, executive director of the Gardens. “Her work is both intricate and ageless.”

For Howe, it’s not a matter of wanting all these different partnerships—she does—but making sure she has the bandwidth to do it all. “The cool thing about having your own business is that the sky’s the limit,” she says. But she also has to be able to keep up with all the work.

For now, she’s bent over her table diligently working away, adding another blade to the jar. Says Howe, “I just keep cutting and cutting and cutting until it’s ready.”