Arts & Culture

Down the Stretch

Legendary painter Raoul Middleman, at 80, seems intent on riding hard to the finish.

Raoul Middleman steps into the University of Maryland University College’s art gallery, starts chatting up curator Brian Young, and, looking around, stops talking mid-sentence. Seeing UMUC’s retrospective of his work, Raoul Middleman’s Romantic Expressionism: Honoring 55 Years of Artistic Excellence, for the very first time renders him speechless, though just momentarily. Middleman’s eyebrows rise over the frames of his glasses, and his eyes twinkle as he takes in the scope of the show, which features 80 of his best pieces and remains up until the end of August.

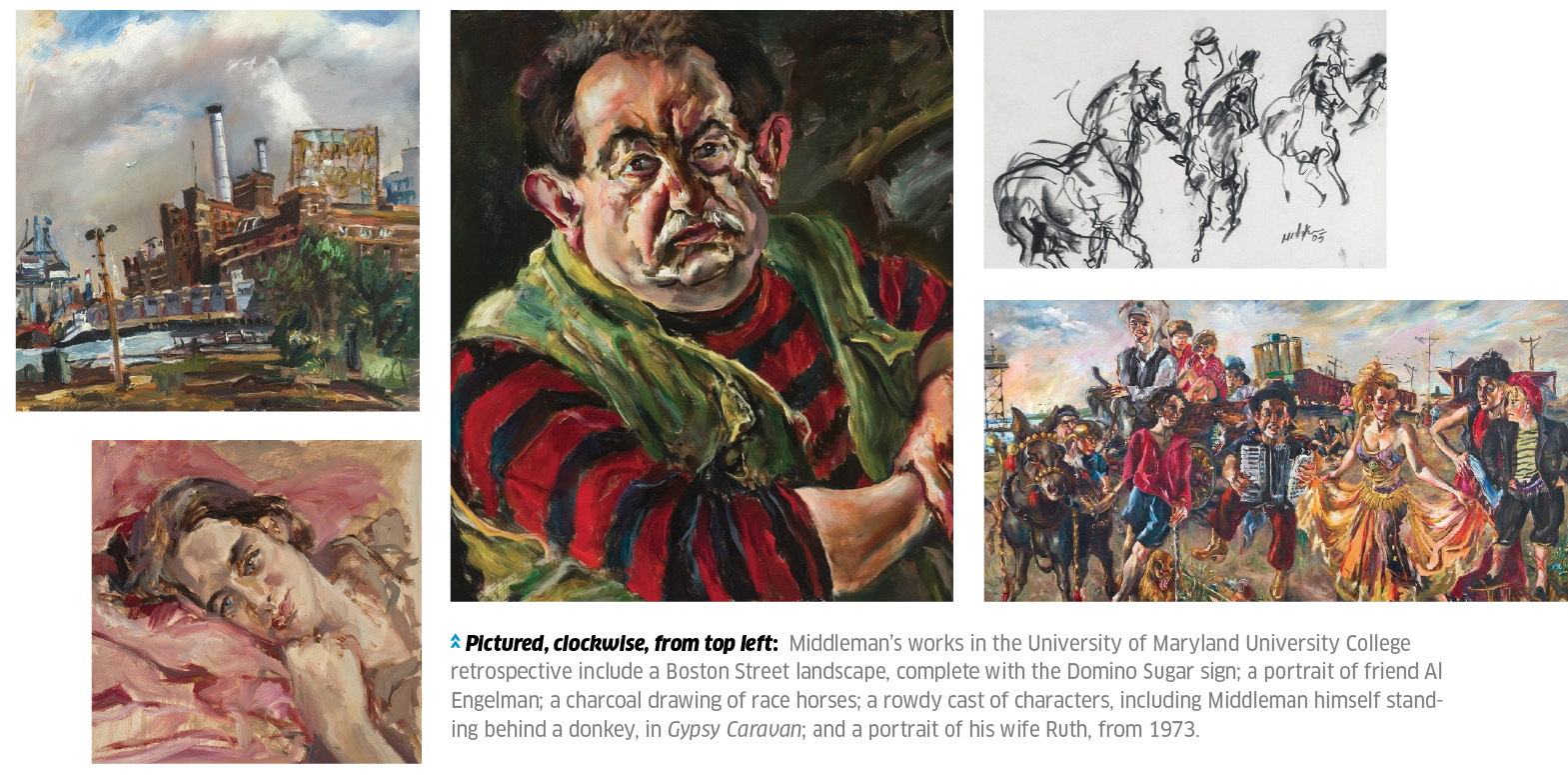

His surprise quickly gives way to recognition. “Look, it’s Al!” he exclaims, taking leave of Young and sounding as if he just spotted a dear friend, which he has. But the room is otherwise empty; friend Al Engelman is framed, larger than life on the wall. “That’s the first portrait I ever did of him,” adds Middleman, a warm smile spreading across his face.

He then spots more friends, Uncle Sid—”my favorite uncle, the first one to buy my paintings;” Bow Davis, a former colleague at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), where Middleman has taught since 1961; renowned painter Grace Hartigan, another MICA friend; his wife, Ruth; his three sons: Ben, Nate, and Raphael; Carole Jean Bertsch, “a great spirit”; and Gloria, a night guard at MICA.

The 80-year-old artist appears genuinely moved by these encounters and the images and stories they conjure. “It’s a lot of family in my paintings,” says Middleman. “All these people are close friends, people I know.”

Middleman moves through the gallery like he’s navigating a receiving line, past the portraits, landscapes, still lifes, watercolors, and a selection of graphic work that includes lithographs and a woodcut. At one point, he turns a corner and practically shouts, “It’s Balthus!” after spotting a favorite dog in a piece titled Gypsy Caravan.

The painting is quintessential Middleman, with its full-palette bravado, industrial backdrop, bawdy vibe, and cast of characters including a one-armed waif, swirling belly dancer, and accordion-playing dwarf, all old friends of his. Middleman is in there, too, standing behind a donkey. It pulses with possibility, like anything could happen, and feels epic. Middleman, who is known for working big, quips that it is “fairly large.” It measures 16 feet long by 10 feet high.

Impressed, he hollers to Young: “What a job you’ve done here! My ego can’t get enough of this. It’s a Raoul museum, and seeing all this work together makes it kind of wild and rowdy. It’s a Raoul-dy museum!”

He laughs at that, before stepping back and taking in the entire room. “It’s my life,” he says, “that’s for sure. But you know what? After all these years, I still wonder where all these ideas come from. They never seem to stop.”

Middleman lives, and paints, in a Mt. Vernon row house that he has owned since 1975. He bought it for a buck, when city revitalization efforts included luring young families to this part of town with a promise of cheap home-ownership. At the time, he was married with young children. It’s a spacious three-story house, with afternoon sunlight pouring through the back windows, and a creaky wooden staircase leading to Middleman’s second floor painting studio.

“Raoul goes deep and isn’t afraid to tell a few whoppers along the way.”

Sitting in a wooden armchair, Middleman is dressed in a blue-green flannel shirt, brown corduroys, and athletic shoes. In conversation, he comes across like an erudite longshoreman, mentioning Plato and classic French poetry one minute and referring to “Bawlmer” the next.

With works in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the National Academy Museum, he is arguably this city’s preeminent painter. The New York Times‘ Holland Cotter has praised his “choppy Expressionist brushwork and romantic atmosphere”; The Sun‘s John Dorsey succinctly described his work as being “strong and true”; and Gerald Ross, MICA’s director of exhibitions, claims that “Raoul goes deep and isn’t afraid to tell a few whoppers along the way.”

The room around Middleman is a riot of paint, painting supplies, and paint-splattered furniture. Dozens of works, all self-portraits and still lifes of flowers, are tacked, grid-like, across two walls. Some of them are still wet; all of them were done in the past week or so. He points to a still life of a bouquet, flowers popping against a black background. “That was a 20-minute thing,” says Middleman, who is notoriously prolific. “Everything worked on that one. It was, ‘Bam, there it is,’ one of the best little things I’ve ever done.”

Besides this current stash, Middleman supplies two galleries—C. Grimaldis Gallery on Charles Street and Troika Gallery in Easton—with a selection of work, and he stores an additional 15,000 pieces at a Belair-Edison warehouse. For a recent MICA show of self-portraits, Selfies, he submitted more than 1,000 pieces for consideration; 400 were used.

“My whole life has favored a certain excessivity,” he says, “although my parents didn’t expect me to focus my energies on art. They didn’t want me to be an artist, and I don’t blame them.”

An only child, Middleman grew up in Ashburton, then a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, and attended School 64 and Garrison Jr. High School. His father was a Johns Hopkins University grad, trained as a mathematician and aviation engineer, who eventually landed at the family tobacco business. His mother was eccentric and imaginative, 12 years older than her husband and born in 1893, “the same year as Soutine, the painter,” notes Middleman.

His parents frequented Woodholme Country Club, but that social scene wasn’t to Middleman’s liking. He became infatuated with an altogether different world, after his Uncle Sid took him riding with Jimmy Hector, a legendary horse trainer, for his 11th or 12th birthday. Middleman, who’d been fantasizing about riding horses while playing cowboys and Indians around the neighborhood and watching cowboy movies at the Gwynn Theater, was smitten with the real thing.

It wasn’t long before he was hitchhiking to stables on Old Court Road and working for Hector. “For a suburban Jewish kid, it was an escape,” says Middleman. “I had this whole other life at the stables, grooming horses and shoveling shit.”

During high school—he went to Poly, like his father—Middleman spent the early-morning hours riding at Pimlico with Hector, whom he considered an “ersatz dad.”

He recalls a time when his father wouldn’t loan him the family car for a much-anticipated date, despite the fact that the couple would be attending a country-club dance. Hector stepped up and loaned him a truck for the evening. “It was the manure truck,” says Middleman, “and we hadn’t unloaded it.” He still remembers the look on the valet’s face when he handed him the keys.

Smiling, he adds: “She never went out with me again.”

At Poly, he excelled at math and science and finished after the 11th grade. He enrolled at Hopkins as a physics major but, inspired by professors like esteemed philosopher George Boas, exited with a philosophy degree. At the time, he fancied himself a poet, or novelist.

Four days after college graduation, Middleman hitchhiked west in search of ranch work. He spent a few years as a ranch hand in Montana and as a wrangler in the High Sierras. Discussing this period, Middleman, a consummate storyteller, digresses through various adventures: ” . . . we had dates with these hairdressers in Miles City . . . my head went through the windshield . . . a telephone—which was attached to a tree—rang, so I answered and it was my mother . . . ”

He wrote a novel about his experiences and eventually moved to New Orleans, where an artist girlfriend lived. After he developed writer’s block, she vowed to turn Middleman, who had enjoyed drawing as a child, into a painter. He bought oil paints and painted all over New Orleans, favoring places like the Jax Brewery Wharf near Decatur Street and its “rough seamen and tough broads.”

He worked shelving books at the public library, lingering over the art books, and painted portraits of tourists for 50 cents apiece in the French Quarter. Nine times out of 10, they would tear them up and not pay him. “I was told I was an uglifier,” says Middleman. “But I also learned I had a natural instinct for art.”

“I’ll go someplace I didn’t know I’d ever go, and that’s what keeps it interesting and spontaneous.”

Middleman honed those instincts during a hitch in the Army. He was company clerk for a Virginia-based railroad battalion before his artistic talents were noticed, and he was sent to the College of William and Mary for instruction. That was followed, after his discharge, by stints at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Maine’s Skowhegan School of Painting & Scultpure, and the Brooklyn Museum Art School, where he studied with landscape painter Reuben Tam.

He returned to Baltimore in 1961 and migrated to Martick’s restaurant and bar, where he found a community of similar-minded, artistic spirits. Needing work, he was about to start bartending at Martick’s, but first placed a call to MICA president Bud Leake in hopes of landing a teaching job. Leake, a fellow painter, hired him to teach freshman painting for $32 a week.

Middleman was, from the outset, “a quirky teacher.” He taught at MICA’s B&O station building, before it was cut up and divided into studio and gallery space. In those days, it was so wide open that Middleman rode a bicycle from student to student to check on their progress. At times, he might have students paint with the brush between their toes. Or he’d have them paint with the coffee they were drinking, “anything to loosen them up,” he says. He started drawing with the students, a practice he continues to this day.

He met Ruth, an artist herself, while on sabbatical in Paris, and they embarked on an extensive trip through Europe, leaving as friends and returning as lovers. He convinced Ruth, who’d been living in France for about six years, to come to Baltimore by telling her it was a lot like Naples. “I know,” says Middleman, turned momentarily sheepish by the memory. “But everything worked out.”

As late afternoon throws shadows across the studio, Middleman reflects on his longevity. His artistic output and overall philosophy bring to mind something his fellow Hopkins alum, the novelist John Barth, told Baltimore in 2008: “I intend to reach my peak at about age 80. Then, I’ll go into a very slow decline.”

At this point, Middleman shows little sign of slowing. He sometimes compares himself to a jazz musician improvising on a standard theme, as he might paint the same face over and over. “Each one is a new take, a new feeling,” he says. “Sometimes, I’ll go someplace I didn’t know I’d ever go, and that’s what keeps it interesting and spontaneous.”

But the key, Middleman swears, is being able to ride the feeling, which he relates in terms that would make Jimmy Hector proud. “You always need to have good hands on a horse,” he explains. “If you pull too hard, you deaden the mouth, and they can get away from you. If you give them too much rein, they take over, and you aren’t in charge.

“It’s the same thing with painting. You need to have a good hand on the brush, where you assert yourself, but you’re also resilient to the will of the paint. You have to go with it, but not encumber the creative act.”

That way, it remains fresh, says Middleman, “because doing something conventional is like riding a nag.”