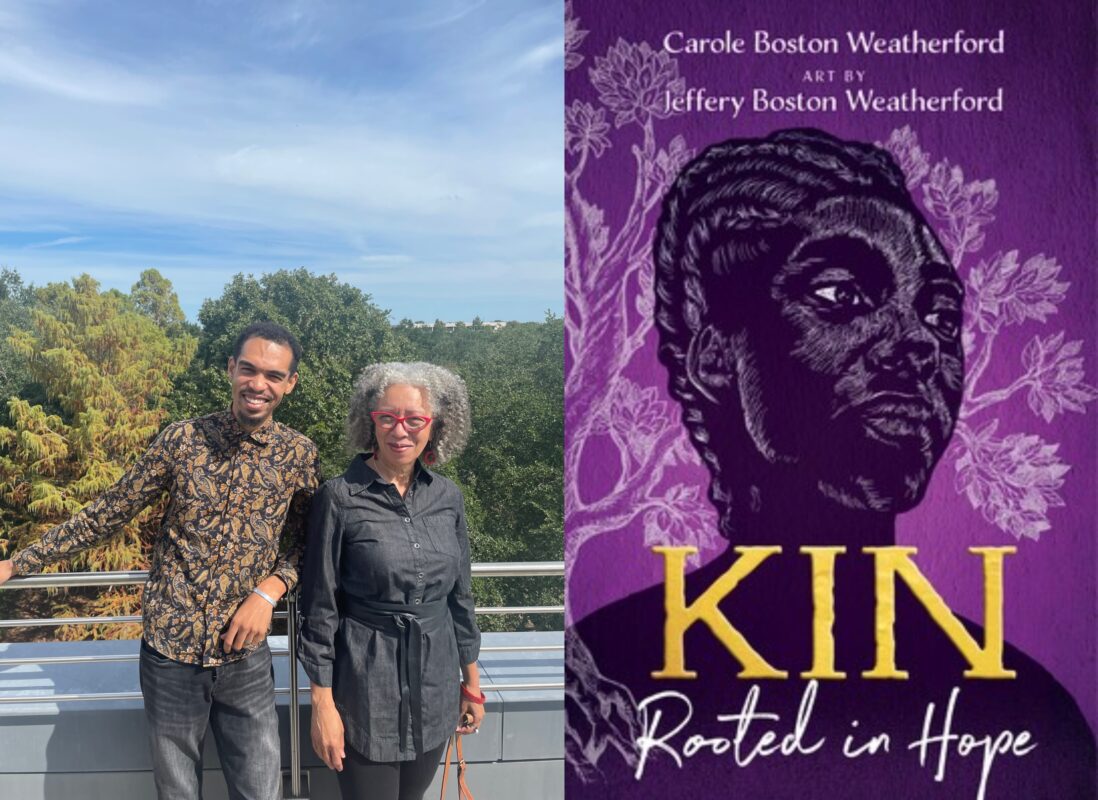

Baltimore native Carole Boston Weatherford has written more than 90 books for young readers, garnering two NAACP Image Awards and 18 American Library Association Youth Media Awards, among many other accolades along the way. But her 2023 novel-in-verse, Kin: Rooted in Hope, is by far her most personal work.

Illustrated by her son Jeffrey Weatherford, Kin reimagines the lives of their ancestors: Black Marylanders who lived through slavery and reconstruction on the Eastern Shore, including those who founded the Black towns of Copperville and Unionville in Talbot County.

Kin was recently announced as the 2025 One Maryland One Book winner, and the nonprofit Maryland Humanities will be providing thousands of free copies for community book discussions across the state.

As Weatherford prepares for her fall 2025 OMOB author tour, she spoke with us about the power of reclaiming her family’s history.

As you were reimagining stories about your enslaved ancestors, what did you allow yourself to make up, and what did you want to be sure was accurate?

I assembled as many facts as I could and then I built stories around them. For example, one of my favorite poems in the collection is about an enslaved girl named Prissy. From the historical record, I knew the year of her birth and who her parents were—my fourth great-grandparents. I knew through my research that house servants often wore hand-me-downs from the master’s family, so I have her discuss that.

I also have her glancing at her reflection in a gilded looking glass, because I knew Wye House [the former plantation in Talbot County where Weatherford’s ancestors were enslaved] had the longest mirrors in North America at the time. I knew from Frederick Douglass’s autobiography that entertaining at Wye House [where he also grew up] was a lavish affair, and that sometimes guests stayed for days or weeks. And I knew from other accounts written by enslaved people that sometimes the white men propositioned women working in the house.

So I constructed this story where Prissy is approached by a guest who says, I’d like to have a taste of you, and she imagines that she would like to tell him, you already have because I spat in your soup. I constructed the story around what I did know, and then I embellished. And I don’t have any problem with doing that, primarily because it’s the story of my people. They didn’t get a chance to tell their stories, so I am free to imagine what her life might have been like.

In addition to reimagining the lives of your enslaved ancestors, Kin also highlights the important role Black families had in state history. When did you realize that yours were two of the “founding families” of Maryland?

I first heard my ancestors referred to as founding families when I went to the [2015] Ruth Star Rose exhibition at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum. I had read that residents of Copperville and Unionville were depicted, but I was not prepared for the scope of the exhibition and to see my ancestors’ faces in these paintings.

I was overwhelmed. There was a photo on the wall of the gardener who worked at Hope House [in Talbot County], and it was my great grandfather, whose face I had never seen. There was a portrait called “Moaney Boy on the Stairs,” whom I’m pretty sure is my dad.

The exhibition’s curator, Barbara Paca, called these folks “founding families,” so that was how I got the term. I knew that my ancestors founded these little villages, but I didn’t think about them in the same way that I thought about Lord Calvin and Lord Baltimore—all the folks we learned about in Maryland history. I’m very proud of this fact in my family lineage. Kin is ultimately a story about Black excellence and the role that my ancestors played, both during enslavement and after emancipation, to make Maryland what it is today.

What advice do you have for other Black Marylanders who are hoping to learn more about their family history?

Don’t be discouraged. Many African Americans hit a brick wall at 1870, because that’s the first census when African Americans were counted as individuals. Prior to that, we were counted as property. So trace your lineage back as far as you can, but understand that while names and dates and places are the roots and the branches on the family tree, the stories are the foliage. Free yourself up to tell stories, to collect stories, to reconstruct stories, to reclaim narratives. That’s very important.

One reason why I wrote Kin, and why I continued to write about the enslavement period, is because of the millions of Africans and their descendants who were enslaved in the Americas, only some 200 had their first-hand stories published. Not only have names and dates been lost, but stories have been lost, and it’s up to us to reclaim them.

This October, you and your son, Jeffrey, are going on a One Maryland One Book tour, with stops at several locations in the state. What do you want Marylanders to get out of these presentations?

I want people to understand why enslaved people didn’t revolt. I want them to understand that the specter of family separation was perhaps one of the greatest fears that enslaved people had. I want them to know the value of research, and genealogy, and of reclaiming lost narratives. Every family deserves to have stories, and every family needs to have stories. They get passed down. Knowing your history is generational wealth—you can’t take it to the bank, but nobody can take it away from you, either.