Arts & Culture

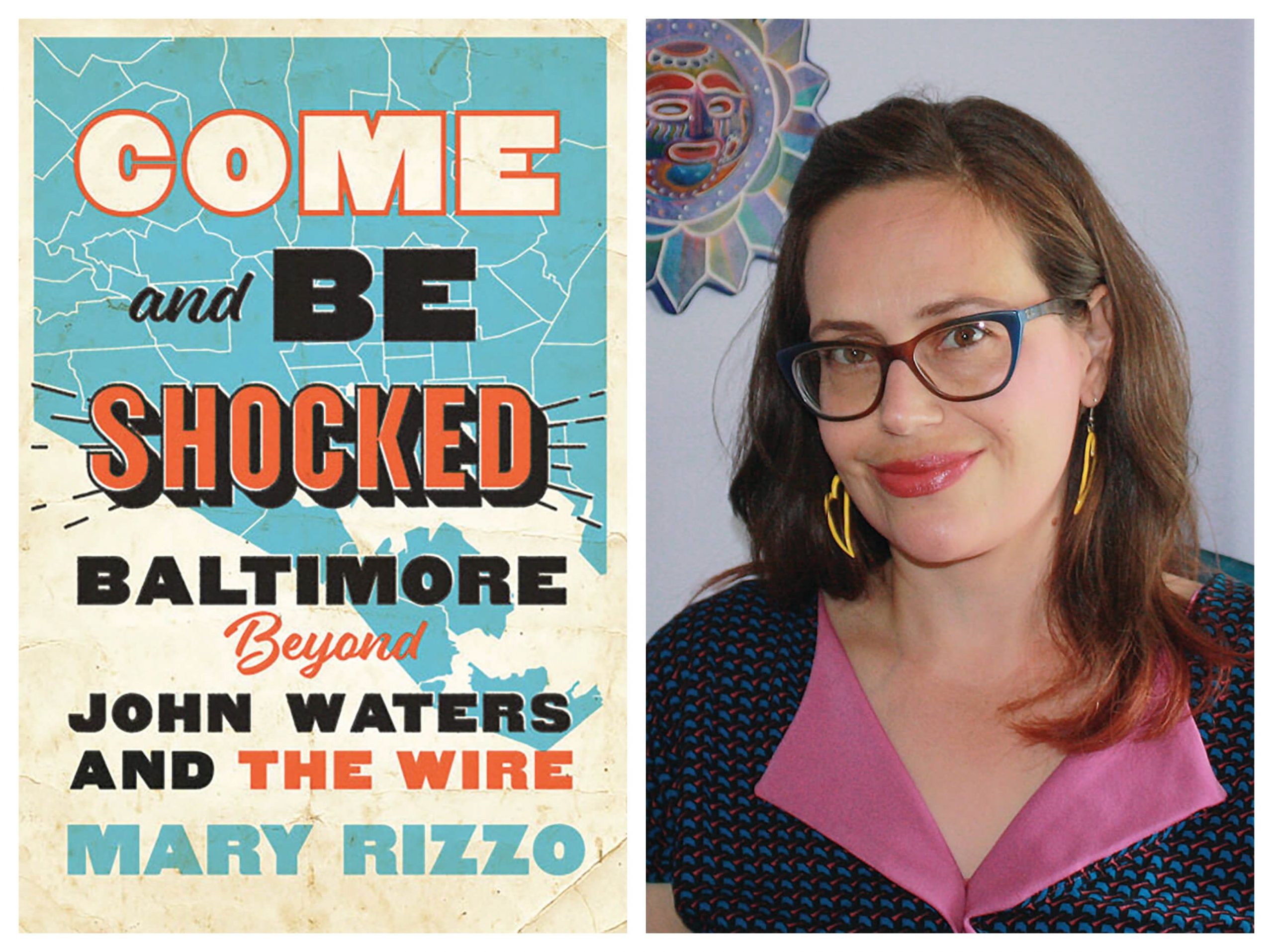

Author Mary Rizzo Examines The Arts’ Role in Baltimore’s Identity

We talk to Rizzo about her new book, ’Come and Be Shocked.’

You study U.S. history. What struck you about Baltimore’s identity in particular that made you want to write this book?

I’d been studying HonFest for a few years when I got the idea for this book. About a decade ago, I was being filmed for a reality TV show pilot about a group of Baltimore Hons, which was a surreal experience. But even though the show never got picked up, it made me realize that Baltimore had a cultural meaning. It meant something to people, even those who had never been there. Culture was part of what defined that.

This was solidified for me in 2016 when former Baltimore Mayor and Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley ran in the Democratic primary. It seemed like someone at every debate and interview asked him about The Wire, a fictional TV show about Baltimore’s drug trade. This cultural text about Baltimore had become the image of the city, so much so that it affected national politics. I wanted to dig into how that happened historically.

How did you get involved with HonFest?

I learned about HonFest through a documentary film about social class in America called People Like Us in 1999. At the time I was in grad school, studying class identity and culture and was fascinated by HonFest. I went that summer. Back then, HonFest was more a regular neighborhood festival, rather than the behemoth it is now. But it still had the Best Hon competition in which women dress up as Baltimore Hons, or white working-class women of the 1960s. That year, and for a few years after, I interviewed Hons, business owners, neighborhood residents, and people on the street, trying to understand this phenomenon of reviving this kitschy history while Hampden was gentrifying.

While I’m critical of how HonFest simplifies Baltimore’s history to make it palatable for tourists, through this research I got to know some of the Hons, like Rita Moore, Heidi Moore Trasatti, and Charlene Osborne, who are lovely, generous people, and who dress up as Hons with a great deal of respect and love for their family history.

Why was it important for you to look at Baltimore’s history through the lens of the arts, rather than, say, business/industry, ethnic customs, neighborhoods, or other factors that play into a city’s identity?

The arts are connected to all those things. We often think of art as a separate sphere unsullied by the base concerns of the world, but the arts have been connected to politics, the economy, and racial, ethnic, and neighborhood identity in Baltimore for decades. In fact, it’s the deep relationship between politics, the economy, and the arts that makes it an important lens to see Baltimore’s history through. I argue that starting with Mayor William Donald Schaefer’s administration in 1971, the arts explicitly became a way to create an image of Baltimore to draw visitors and new residents and an economic force in their own right. From the Charm City PR campaign in 1974 to Artscape today, the city government has made art and image central to the city’s renaissance.

In what ways can the arts can be more effective than politics in ushering in new movements?

Look at John Waters’ early movies. In Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble, he’s got these great scenes of Divine with full makeup, dress and heels, sashaying through downtown Baltimore like she’s on a fashion runway. Those are real people reacting to her, not extras. Imagine what it was like for queer kids around the country to see someone so unabashedly and visibly queer walking on public streets in the middle of the day. At a time when a gay rights movement was still cohering, Waters’ films had a pretty radical vision of gender and sexual non-conformity. I think you can draw a line between those films and what trans and gender nonbinary activists are doing today.

You, as well as others, write about Baltimore being a city divided. Do you see ways in which people or ideas are bridging that gap, or do you see it widening?

One of the points I make in the book is that Baltimore is a microcosm. Its problems are the problems facing all medium-sized cities in this country. Baltimore’s problems are America’s problems.

I’d like to be hopeful, but I don’t see substantive, positive change happening in our current political climate, either locally in Baltimore or nationally. It’s not just a republican versus democrat issue. It’s an issue of promoting policies that will benefit average people, not just those at the top. For decades, Baltimore prioritized its image to outsiders over the needs of its people, which exacerbated divisions by pumping money into downtown areas to spur gentrification and displacement. That needs to change.

Art has a role in this, by the way. Artists have big imaginations. They can help us understand the problems facing the city in nuanced ways, like David Simon does in The Wire or Theo Anthony in Rat Film. They can also help us come together to find solutions. I’m so inspired by the young poets I’ve met through Writers in Baltimore Schools and DewMore Baltimore who definitely have the vision to help us map out a better future if we listen.

Can you talk a little about the Chicory magazine you discovered during your research for this book, and why you were inspired to make it available online?Chicory was a magazine published by the Enoch Pratt Free Library from 1966 to 1983, thanks to two librarians, Evelyn Levy and Thelma Bell. Using money from the War on Poverty, they hired local poet Sam Cornish who worked with kids and teens in East Baltimore, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city, to create a poetry and art magazine.

What made Chicory special was that it wasn’t edited. What people submitted was basically published as is. They even published what the editors overheard as a kind of poetry called “Street Chatter.” For a historian, this is an amazing peek into what regular people thought about the world during a tumultuous time in the city’s and country’s history. People wrote about local and national politics, from the 1968 riot to police suppression of the Black Panther Party. They also talked about their daily lives. This magazine was the voice of black, working-class Baltimore in its time. And some people who published in it went on to become well-known writers, like poet Afaa Michael Weaver, Terry Edmonds, the first African American presidential speechwriter, and journalist Rafael Alvarez.

Because its content is still relevant, I wanted to make sure that it was accessible to folks today. I worked with Pratt to digitize the collection, which is now online through Digital Maryland. You can also follow on Instagram, where we feature poems and art from the magazine.

Read our review of Rizzo’s latest book, here.