Arts & Culture

Baltimore Architect Jerome Gray Paints the City in Watercolor

Since 2016, Gray has posted more than 3,300 architectural watercolor sketches—complete with brief histories—on his popular Instagram feed.

“I once heard Quincy Jones tell an interviewer when he had an idea, he got it down as fast he could,” architect Jerome Gray says, opening a palm-sized watercolor set across the street from The 501, a midcentury modern apartment building on the edge of Seton Hill. “If it was 3 a.m. and he needed the best bass player in LA, he’d bring him to the studio tired, drunk, hungover, whatever. Better if they were tired because they wouldn’t overthink anything. You’re just capturing the essence.”

With that, Gray counts The 501’s front-facing windows and dashes off the frame of the building in a few pencil strokes. He immediately begins adding color—the pale blue sky absorbed in the building’s white facade, the midday sun reflected in its glass, its rust-orange accents. He chats through the entire exercise, which lasts just minutes. Then he walks to the corner, takes in the new perspective, and does it again, this time without an outline, only watercolor.

In a previous iteration, The 501 was owned by The Hardest Working Man in Show Business and named the James Brown Motor Inn. Opened in 1964, it mostly served a white business crowd before Brown purchased it for $5,000,000 in 1970. An FBI raid and developing “reputation for rowdiness” at the inn’s nightclub soon forced Brown to sell.

As Gray notes on his popular Instagram feed, where he posts brief histories alongside his watercolors, The 501 was designed by Baltimorean David Harrison, who also did Dolfield Plaza and Brooklyn’s Patapsco Theatre, which today has been repurposed into a church.

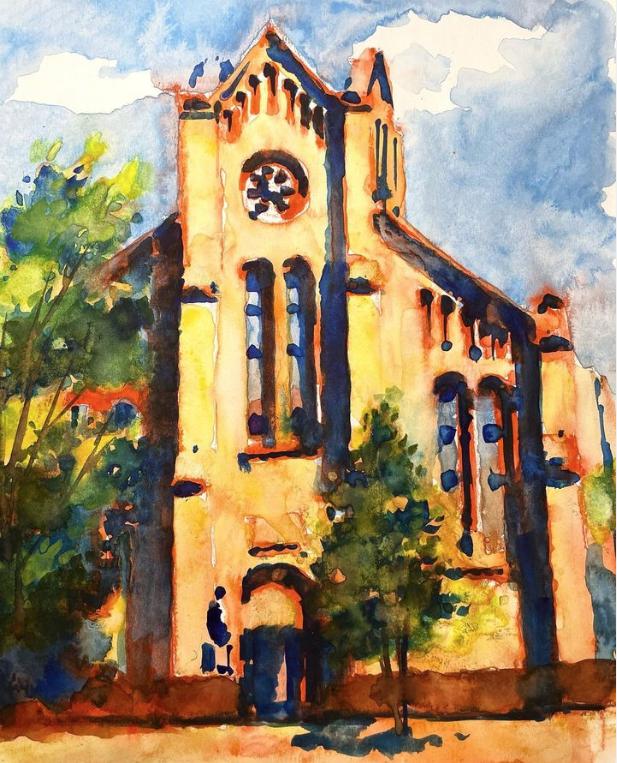

Over ensuing lunch breaks, Gray returns to Seton Hill, capturing the former home of a candy company and a furniture store owned by a man who also operated an illegal saloon during Prohibition. Many of his subjects are familiar—Camden Yards, the city’s gothic cathedrals, the American Visionary Art Museum, and the Art Deco Senator Theatre (pictured above), designed by John Jacob Zink, who studied at the Maryland Institute and did the iconic Patterson Theater as well. Everything is fair game and the watercolors that get the most engagement are often the fading, occasionally vacant wonders most of us pass by without noticing, including the 1870-built Home of the Friendless building on Druid Hill Avenue.

Since 2016, Gray has posted 3,300 sketches. “I’d gone into business for myself and it wasn’t ‘going’ yet, and my wife told me I needed to get out of the house,” he recalls. “She said, ‘Didn’t you used to draw?’”

Most of his works depict Baltimore’s built environment, although there are sketches of D.C., Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland—“a city with great architecture”—and Detroit, his hometown. Emulating an older brother who drew, Gray got good with a pencil at a young age and excelled in the architecture program at Detroit’s legendary Cass Technical High School, whose notable alumni include John DeLorean and Diana Ross.

“I was in a good-size class of Black kids, if you can imagine this in the 1970s and 1980s, who were put through the wringer,” he says. “My best friends were in the program, and we were all going be architects. Lo and behold, three of us became architects. The fourth one became an engineer.”

Completely unplanned, his watercolors garnered attention from local architects, historians, and preservationists and became a career boon, leading to exhibitions and commissions. Gray gave the keynote address for the 2019 Doors Open weekend sponsored by the American Institute of Architects-Baltimore and joined the Baltimore City Historical Society board. He now regularly presents on urban architecture and history.

Are there buildings he wants to get to? “Always,” he says, naming WEBB’s old radio studio, which James Brown also owned, in West Baltimore’s Fairmount neighborhood. He also wants to check out the views from Johnston Square on the east side.

“The one I want to do, but can’t, is the Mechanic Theatre, which was demolished. There are good reasons to knock down buildings, but there was no reason to demolish the Mechanic. It was designed by an important American modernist architect, John Johansen, whose work in other places is celebrated. The Mechanic was an amazing exercise in broken-form concrete. It was this complex, broad-shouldered, tough building that was honest to what it was—a concrete building. It was corrupted over its time, but it should’ve been loved. Instead, we still have a big hole in the middle of the city eight years later.”

(Gray warns not to get him started about McKeldin Fountain, another brutalist landmark demolished with support from the Downtown Partnership.)

“One of the significant things about modernism, which is about the only architecture movement people don’t seem to like, is brutalism,” Gray explains. “You may not like it, but it played with form and depth and shadow and light better than just about anything. I think what people like [in my sketches] is the color and the contrasts, but that’s the thing, the architect’s vision, I’m trying to communicate.”