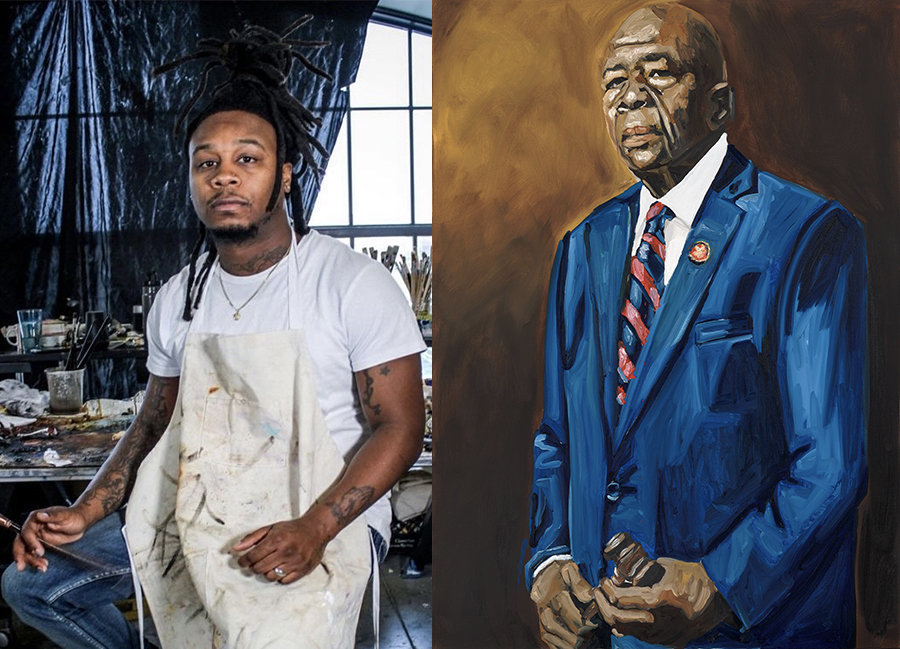

Baltimore artist Jerrell Gibbs stands near six feet tall. His locs—which he says have been growing since 2015, the year he started to focus on his painting—flow just over his shoulders. His approach to growing and maintaining such a beautiful hairstyle, rich in history and culture, isn’t unlike his approach to portraiture, which he says takes both patience and practice.

An MFA graduate of MICA—whose work is in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles Museum of Art, CC Foundation, X Museum, and our own Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA)—Gibbs adapts his work from small Polaroids and grows them into life-size paintings. Throughout his career, the 33-year-old has become known for examining his Blackness, class, and personal life—both the joyous moments, as well as issues surrounding politics, race, and economic disparities—in his work.

It was for this reason, in part, that he was chosen by a BMA selection committee to paint the official portrait of the late Rep. Elijah Cummings, which will be on view at the BMA through January 9 before moving to its permanent home at the U.S. Capitol. Congressman Cummings, who represented Maryland’s 7th District for more than two decades, was perhaps best known for his legacy as a civil rights leader, fighting for his constituents on issues including voting rights, gun control, and restructuring the criminal justice system.

“We are exceedingly pleased with the result,” Cummings’ widow, Dr. Maya Rockeymoore Cummings, who spearheaded the commission, said in a statement issued last month. “Jerrell Gibbs is a masterfully expressive painter and his stunning portrait perfectly captures Elijah’s essence and majesty. It is a timeless masterpiece.”

Before the piece heads to Washington, D.C., we caught up with Gibbs to discuss his local upbringing, artistic process, and capturing the iconic civil rights leader and Baltimore advocate.

Tell us a bit more about how you were selected to paint the official portrait of Rep. Cummings?

They started out with 30 or so artists and then they narrowed it down to three of us, [myself,] Monica Ikegwu, and Ernest Shaw. They did studio visits, and my first one was actually on my birthday, March 8, 2021. [BMA director] Christopher Bedford, Maya Rockeymoore Cummings, and some other folks came to visit me when I was working out of my home in March during the pandemic. After the studio visits we had to submit a sketch by April 2021 to render what we might do if given the opportunity to execute the portrait of Elijah Cummings. I opted to submit an actual painting after a number of sketches that just didn’t resonate with me. The painting really swayed the committee to go in my direction.

What are some of the things that stood out to you about Rep. Cummings while looking for inspiration?

I met Elijah Cummings in person one time at a mayoral inauguration—it had to have been 2015 or 2016. He didn’t know me, but he knew someone that I was with, and we all spoke. And then we ended up taking a picture together, all of us, it wasn’t just me and him. Even in that short meeting, I had recognized that he had a presence and an aura. But he obviously wasn’t trying hard, it was just natural. He wasn’t trying to be loud or over the top to make himself known. In preparing for the painting, I did a lot of research. I watched a lot of videos, listened to a lot of audio clips, and read his book. What really resonated with me the most was the command that he had in the courtroom, the presence that he brought, the integrity and his strength, you know? Those were the things that really sat with me. And those were the things that I was interested in. I could gather that he had to have been very strong.

The New York Times recently reported that there were actually some components of your original concept painting for Elijah Cummings’ portrait that didn’t make the final cut. How much did the concept of simplicity, perhaps in the work of other artists you’ve studied, sway that decision?

Mentors—folks I really respect and admire, like my wife, Sheila, elders, and others—always say things like “less is more.” At times I’ve felt insecure about something I might be working on, or I’ve felt like I’m not able to do something, or I’m not enough. We’ve all had those moments where we might be comparing ourselves to other people. By doing all of that, we end up over-thinking or doing too much. But when you’re really in the groove, you know how to just do whatever you need to do and not add anything extra, and that’s certainly how I felt in doing this portrait. I like to focus only on what’s important in my art. I’m actually comfortable with doing less these days.

How has your family (in Baltimore and beyond) responded to you being selected for this? Does the conversation at family dinners shift to talk about these accomplishments?

It’s weird right…It’s not a space that Black people outside of the art space really occupy. A lot of us don’t really stay current on what’s happening in the art world. Because my family isn’t necessarily in the art field, when something of this magnitude happens it’s definitely something we celebrate and talk about. But it’s really a blessing, too, because when I’m with my family I just want to be Jerrell, I want to spend time with my family, I want to know what they’re up to. [It’s nice to] chill and allow family to be family and for my art world to be separate.

Where in Baltimore are you from?

I was born, raised, and always lived in West Baltimore. We lived in a lot of different neighborhoods because we moved a lot after my father was killed. I lived in Park Heights close to Hilltop Shopping Center, Woodlawn, Liberty & Garrison, Chadwick. Just so many different areas, but I always just say West Baltimore to make it simple. I went to Hilton Elementary, Chadwick Elementary School, Johnnycake Elementary School. But by the time I got to high school and things started to settle down for my family, we really nestled in Baltimore County. I’ve lived in Baltimore County pretty much since then. I lived in the city again with my aunt for a short stint during graduate school at MICA, but now I’m back in the county with my wife and our daughter.

Everyone has those defining Baltimore moments. What are some of the things you did with your family here that helped to shape who you are today?

Something that I used to always do every weekend was get together with matriarchs of my family and my sister. We would always go over to my aunt’s house and my grandmother’s house, who all used to live off Lewiston Avenue in West Baltimore. They literally lived like two houses from each other. With them all living so close together, every Friday we had our ritual to get together and walk to the local Chinese food spot where we’d get our egg foo young, shrimp fried rice, and all that. The store was on the corner of Park Heights and Rogers Avenue. It was right across from this liquor store named Peppers. There was also this field of grass with a clear-bleached grass path in it where people would walk to Hilltop Shopping Center. One of my favorite memories growing up was walking through that field to get Lemonheads and Boston Baked Beans with my grandmother. The MVA stands where that field used to be, and some of the store’s names have changed, but I still have those memories.

What inspired you to start painting six years ago?

I don’t know what necessarily inspired me, but I remember how the process went. I’m very process-driven. After I dropped out of college for the second time, I left Bowie State University and I was working two jobs—one during the day and my second shift was from 11 p.m. until 7 a.m. One night at my second job, I just got the urge to draw again. I actually used to draw when I was a kid, and then left it alone. I consistently kept drawing and I would show my wife pictures of the things I had drawn. That Father’s Day, following my inclination to start doodling again, she got me some painting supplies and an easel. Once I started painting, I knew it was something that I was passionate about because I didn’t want to do anything else. All I wanted to do was paint, learn about other artists, study, read about painting, watch YouTube videos. It’s all I could think about.

Who were the first artists whose work you were able to familiarize yourself with and relate to?

The first person that comes to mind is Jacob Armstead Lawrence, who was a Harlem-based painter known for his portrayal of African-American historical subjects and contemporary life. The impact of his work has really resonated with me. I gravitated to Lawrence obviously because he’s an African-American artist, but also because he focused on our culture, which I also love to do in my own work. Ernest Eugene Barnes Jr. is another artist whose work has significantly portrayed African-American culture.

To what, or whom, do you owe your success?

Black women have supported me my whole life, and they still continue to. Black women—like my mother, my wife, my grandmother, my aunt, and even my daughter—are all my foundation. In my formative years when my father was killed in Baltimore, and even as I made room for myself in the arts world, Black women were there for me. There’s something about women, they have this ability to take on anything of any magnitude and still make it happen. Especially Black women, they have the capability to do things I’ve never seen done before. Watching my mother raise three children as a single mother in Baltimore, seeing my wife do what she does, my mother-in-law—it’s all just inspiring. They have all helped mold me and allowed me to grow myself further than I could have ever imagined. And I’m sure Elijah Cummings would’ve said the same about Maya Rockeymoore Cummings and the women in his life.

[Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]