Arts & Culture

Baltimore Carpenter Creates a Literal Old-School Smalltimore

By day, Matt Hankins is a shop supervisor at Worcester Eisenbrandt, a historic restoration company that's nearly 100 years old.

“Norman Rockwell originally painted that billboard image for Amoco,” says Matt Hankins, holding a tiny, once-upon-a-time gas station in the palm of his hand. “That woman in the advertisement? It’s Grandma Moses. They were friends, and he occasionally painted her portrait,” Hankins adds, gesturing to the kindly visage of the elderly woman reaching for a few coins in the worn poster. (Amoco tag line: “Easy on the purse.”)

The entire billboard, the size of a couple of postage stamps, is situated atop a diorama of a very real Amoco service station that decades ago sat at the intersection of Park Heights and Oakford avenues in West Baltimore.

The unique, white-stucco structure remains today, but with the pumps and repair bays long gone. In the uncannily precise recreation, there’s a mechanic checking beneath the hood of a mid-1940s Ford sedan, a man and woman in polite conversation on the corner, a mother in front of her rowhouse pointing her son’s attention across the street—perhaps to an Arabber—and a middle-aged guy in an undershirt who looks like he’s ready to crack open an afternoon Natty Boh on his stoop.

The human figures, exquisitely designed and painted, are all of three-quarters of an inch tall. “It’s funny,” says Hankins, a preservation carpenter by vocation and model builder by avocation, “everybody does the same thing. They start inventing stories about the people. I do it, too.”

By day, Hankins is a shop supervisor at Worcester Eisenbrandt, a Baltimore-based renovation and restoration company, which itself is nearly 100 years old.

Most of the buildings in their portfolio are either listed on, or potentially eligible for, the National Register of Historic Places. Local efforts have included work at the Hippodrome Theatre, Peabody Institute, Clifton Mansion, the Canton Library, and the Recreation Pier at Fells Point—now the Sagamore Pendry hotel. In 2015, Worcester Eisenbrandt, with Hankins assisting, performed the facelift for the Washington Monument’s 200-year anniversary.

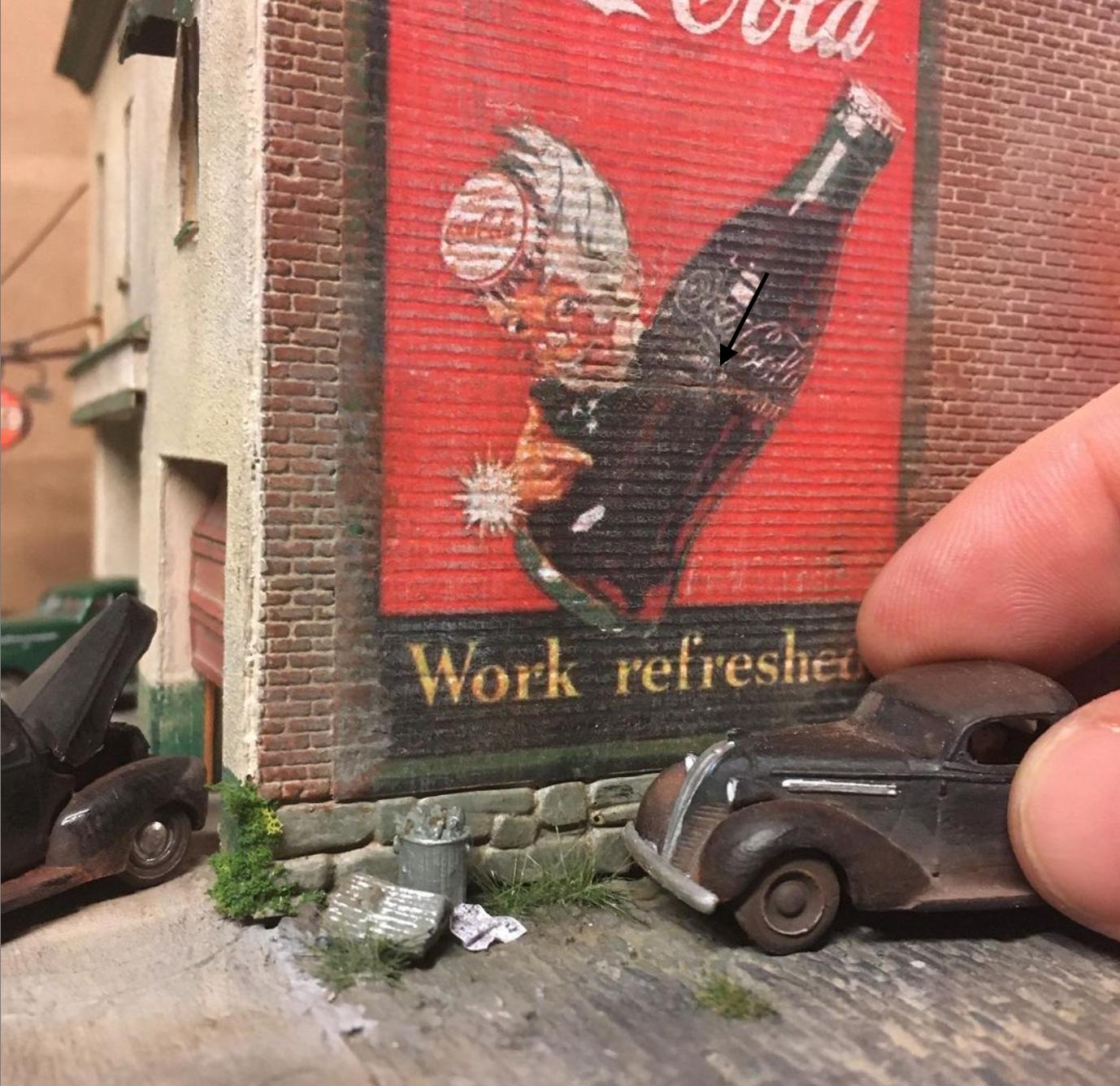

Hankins loves his job and pursues his hobby with equal passion in the vast basement workshop of his Charles Village rowhouse. Hankins not only recreates, but appropriately ages, what are essentially train-model size cityscapes to scale (1:87).

Some projects are based on personal observations of fading facades and “ghost” sign advertisements that linger on the sides of old Baltimore buildings, promoting brands that were produced here, like Noxema and Arrow Beer.

Other times, he builds things that no longer exist, but did. He rebuilt the since-demolished Light Street Pier ferry station from archived photographs, adding several nuns in full habit among the passengers.

“Everyone always asks where the nuns are headed,” he says. Like all good hobbies, modeling requires skill and creativity. Miniscule green “grass” fibers, for example, are made to stand up by sending small electrical shocks into the glue in which they’re placed. It also requires the ability to procrastinate real-life demands.

“When we bought our rowhouse, I told my wife it would be a 30-year renovation project. That was 16 years ago. Progress-wise, I’m about two years in.”

In photographs of his work, which he posts to Instagram (@restocarp) and Twitter, but even more so in person, the seemingly impossibly miniature size and detail of his work has something of a fantastical effect. Normally, of course, a person can’t hold a city block or street corner in his or her hand and turn it around for closer examination.

“There’s a hyper-realistic quality that captures people’s imagination,” Hankins says. “They begin to consider certain details they haven’t before.”

In December, Hankins plans to display some of his historically informed work as part of a much larger train garden at the TownMall of Westminster, per Maryland Christmas tradition. He’d also like to display his work at a venue like the Baltimore Museum of Industry at some point. Meanwhile, he jokes, all his models inevitably remain works-in-progress, forever available for tinkering and additions.

“The only thing ever completely finished was a model train garden that my father—who taught woodworking at St. Paul’s—and I did together when I was a kid. We finally got trains running one Christmas,” Hankins recalls. “It was really nice. Built into a coffee table, working perfectly. Then, our cats climbed up underneath and ate the exposed wiring.”