Arts & Culture

Changing of the Guards

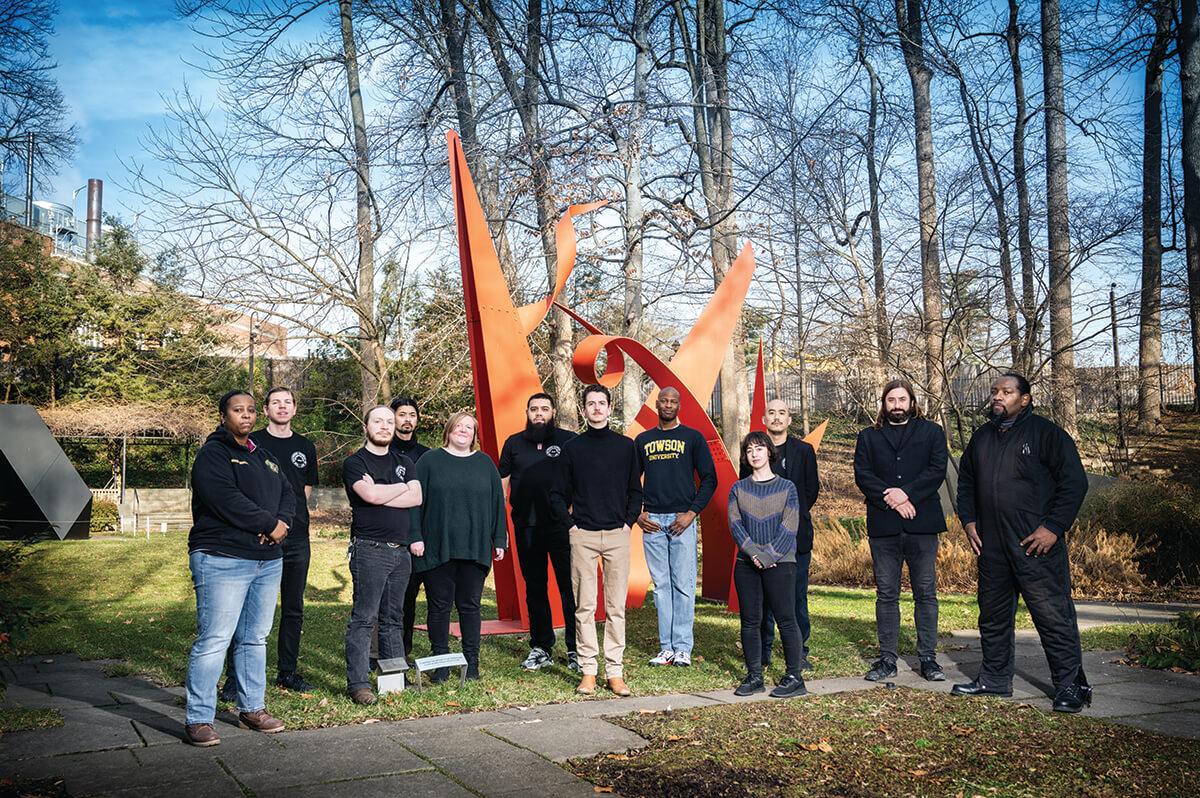

Security guards showcase their curatorial talents at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

he last time the Baltimore Museum of Art was in the headlines (excluding director Christopher Bedford’s resignation announcement in February,) it was for the deaccessioning scandal that rocked the art community. So it must’ve been a happy surprise—maybe even a bit of a relief—when, last July, the museum announced its new “Guarding the Art” exhibit, and there was so much enthusiasm, it crashed the museum’s website.

he last time the Baltimore Museum of Art was in the headlines (excluding director Christopher Bedford’s resignation announcement in February,) it was for the deaccessioning scandal that rocked the art community. So it must’ve been a happy surprise—maybe even a bit of a relief—when, last July, the museum announced its new “Guarding the Art” exhibit, and there was so much enthusiasm, it crashed the museum’s website.

It’s not so much the content of the new exhibit that makes it remarkable, though the works do come from the 108-year-old Charles Village institution’s world-class collection of over 95,000 objects, some of which have never been shown before—but rather those who have chosen it.

The exhibit, to be on display in two large galleries adjacent to the museum’s famed Cone Collection starting on March 27, is being curated by 17 of the museum’s security guards.

Ranging from a grandmother of nine to a Towson University senior majoring in classical voice performance, the participating museum guards bring a diversity of backgrounds and life experiences to this innovative exhibit. One guard is a former healthcare worker, another a bartender, another an adjunct instructor at the Maryland Institute College of Art, who teaches courses on horror movies. It’s these unique perspectives that the museum aims to put on display, along with the actual artworks.

“Being a guard is so much more than telling people to turn off their flash, to take a step back,” says Elise Tensley, who has been a security guard at the BMA since 2017. “This isn’t just a show about the BMA’s collection, it’s a show based on what we have to offer.”

After all, the security guards might be more familiar with the museum’s collection than most people who walk its halls.

“They probably spend more time than anyone at the museum thinking about and connected with the art,” says Amy Elias, a BMA trustee who conceived the exhibition with chief curator Asma Naeem. The two also enlisted the help of noted art historian and curator Dr. Lowery Stokes Sims, currently the Kress-Beinecke Professor at the National Gallery of Art’s Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, who also provided mentorship to the guards.

“I WAS IMMEDIATELY STRUCK BY THE

FRESH EYES THAT THEY CAST ON WORKS FROM

THE MUSEUM’S COLLECTION.”

“I was immediately struck by the fresh eyes that they cast on works from the museum’s collection,” says Sims. “Hearing their intensely personal rationales for their choices of objects revived my initial feelings of love and awe in museums, and reminded me why I got involved in art and curatorial work in the first place.”

The guards were given access to the BMA’s full collection, including its massive digital database of material, only a very small percentage of which is ever on display. Each guard could pick up to three objects of their choosing—an individualized, intimate alternative to the typically academic process.

But from the outset, the idea was to have the guards do more than just pick the art. They’d be involved in designing the installation, developing the accompanying catalog, working with the conservation team, and planning the relevant programming. For all that extra work, they’d also be paid, in addition to their salaries. Fundraising for the exhibit, which was ultimately financed by a lead grant from the local Pearlstone Family Foundation, included imbursement to the guards for their involvement.

Tensley, a painter herself who has sold commissioned work, chose “Winter’s End,” a 1958 painting by the late Abstract Expressionist and Park School graduate Jane Frank that has only been exhibited twice. “I wanted to give Jane Frank her moment again, as a female artist with Baltimore ties. I’m 37, and in my entire lifetime, this painting hasn’t been displayed.”

While some guards purposely sought out art from the depths of the museum’s archives, others chose works that were deeply familiar. Dereck Mangus, who has had his own artwork exhibited locally in group shows and whose writing has been published in art journals, selected Thomas Ruckle’s “House of Frederick Crey,” a painting he’d come to know over the course of the six years he’s worked at the BMA, because it depicted the Mount Vernon neighborhood where he lives.

“Every museum I’ve ever worked in has had some sort of staff art show,” says Mangus, who has worked as a guard at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and Harvard Art Museums, as well as the Walters Art Museum, but had never been asked to participate in the curatorial process before. “We’re putting on different hats.”

For Ricardo Castro, a guard since 2019, the familiarity was cultural. Being from a large Puerto Rican family in Delaware, he chose works by artists from Columbia, Equador, and Costa Rica, as a way to honor his heritage.

“It’s a job made of waiting, but it’s also a job of contemplation—we’re seeing everything,” says Rob Kempton, a Maryland native with a master’s in museum studies from Johns Hopkins University who has been a guard since 2016. “It’s a lot of, ‘Where’s the bathroom?’ But you can create experiences, just by getting into a conversation.” He selected works by two renowned local painters, Washington, D.C.’s Alma Thomas and Baltimore’s Grace Hartigan.

This on-the-floor ability to interact—with both the museum-goers and the art itself—was another key element driving the exhibit. Security guards may often blend into the background of a museum, as quiet and stationary as the artifacts they oversee, but they can also participate in the experience—answering questions, offering guidance, becoming part of the discussion.

“There are times when people have questions and there isn’t anyone else to ask besides the security officers,” says Kellen Johnson, the Towson senior who, between his shifts at the BMA, is also a member of the Towson University Chorale and Men’s Chorus groups, and has held solo recitals at the museum.

Johnson chose paintings by the 20th-century German painter Max Beckmann and American painter-muralist Hale Woodruff to reflect his interest in music. Beckmann’s wife, Mathilde, who is featured in the 1939 “Still Life with Large Shell” painting that Johnson picked, was a violinist and singer. Woodruff’s 1928 “Normandy Landscape,” demonstrated his interest in showcasing work by Black artists.

Johnson now cites interacting with museum-goers among his favorite aspects of the job, but when he first started working at the museum in 2013, he initially kept his distance.

“It was just: stand still, don’t interact, and be this invisible presence, except to say, ‘Please don’t touch that,’” he says. “That got very boring,” so he attended lectures, signed up for docent trainings, and read up on the artists, the art, and even the collectors—all so he could bring that knowledge to work. Visitors would ask if he was a docent, says Johnson. “No,” he’d tell them, “I’m just a guard.”

Christopher Bedford, the BMA’s director, would like to give the guards the option to be more than just guards.

“I’m keenly interested in the show because it empowers and foregrounds the authorship of a group of people not traditionally given that role,” says Bedford, now in his sixth year at the museum. “There are [guards] who are interested in ascending the ranks of a museum and exploring the world of art history and curatorial work. This is a way of doing that.”

Bedford sees the informal mentorship of “Guarding the Arts” as one of its most crucial elements—a means to explore, and perhaps ultimately change, how the museum has historically worked.

“There are aspects of the way that we function that just need to be completely turned on their heads,” he says, referring to addressing larger themes of equity, representation, and shared authorship. “This is a way of doing that.” (According to the Association of Art Museum Directors, in 2018, only four percent of curator roles in U.S. art museums were held by African Americans.)

“[Mentoring] is the engine that’s propelling this forward,” Naeem says about the exhibit, “to perhaps create new futures and new careers for some of the guards.” Those guards, she says, “are a true mirror to the public.”

Baltimore native Sara Ruark, who came to the BMA in 2018 and studied film at Towson University, agrees, seeing the guards as a sort of bridge.

“WE SEE NOT JUST WHAT’S GOING

ON IN THE MUSEUM, BUT WHAT’S

GOING ON IN THE COMMUNITY.”

“We’re both outsiders and insiders,” says Ruark, who selected Dutch painter and sculptor Karel Appel’s 1962 painting “A World in Darkness,” as well as a mid-20th century miniature totem pole by an unidentified Haida artist, neither of which she had seen before. “We see not just what’s going on in the museum, but what’s going on in the community.”

This gives the exhibit a sense of accessibility, she says, one that’s particularly relevant to Baltimore’s multifaceted artistic community.

“I think people who don’t realize how rich the art world is here give Baltimore a lot of flack,” says Ruark. Beyond the big-name institutions and exhibitions, “[There are] local artists who sell stuff under a bridge that’s simply stunning, craft shows in decrepit churches—I love that about this city.”

Though this isn’t the first time a museum has put on an exhibit with participation from its own security guards—New York’s Museum of Modern Art staged a show called “Beyond the Uniform” in 2020 that included a playlist from its guards—Bedford says the BMA show wasn’t patterned after anything else.

“It was modeled around the idea that shared curatorial authorship around our hierarchy would yield really unexpected results,” he says. “[Baltimore] is a place that is willing to embrace unorthodox ideas. It’s bold, a little quirky…I’m really hopeful that this will be the first of many exhibitions that will be unconventionally authored, by guards or others. I think it can become a hallmark of the museum.”

“This was a chance to have a real tangible project, with real feedback and results,” says Kempton, who is looking forward to seeing Hartigan’s 1957 abstract painting “Interior, The Creeks” and Thomas’ 1972 work “Evening Glow” on display. “Dr. Sims has said that this show privileges and deprivileges at the same time. It’s demystifying the entire museum process. To see that and to play a meaningful role in that is significant.”

On display through July 10, the exhibition will feature as many as 26 objects. As of press time, an opening reception was still in the planning stages.

Traci Archable-Frederick, a Baltimore native who served in the U.S. Army and Maryland National Guard before coming to the BMA in 2006, chose Mickalene Thomas’s 2021 “Resist #2,” as she wanted a piece that reflected the times, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and in relation to the demonstrations that swept the country in the wake of the George Floyd’s murder.

Thomas’ piece, a collage that combines protest images with acrylic paint, rhinestones, and glitter, was recently acquired by the BMA and joins the Brooklyn-based artist’s installation, “A Moment’s Pleasure,” that has transformed the museum’s East Lobby.

“This was it right here,” says Archable-Frederick. “It was speaking to everything that was happening.”

By choosing art works that speak not only to the contemporary world but to themselves, these 17 guards will be giving a very personal perspective. And yes, they’ll be watching.