Arts & Culture

The Baltimore Museum of Industry Celebrates the City’s Historic Corner Bars

In the museum's latest permanent exhibition, curator Rachel Donaldson taps into the history of Baltimore watering holes from the Industrial Revolution until Prohibition.

There’s the long creak and sudden bang of a screened door as you enter the hottest new bar on Key Highway. To get there, first, you must walk through the corner store, over the black-and-white porcelain tile, past the fading boxes of McCormick spices and 25-cent cans of Eastern Shore tomatoes. But there in the back, beneath the tin ceiling, two chandeliers dangle above a few dozen beer bottles, beckoning visitors to come in and stay awhile.

The only other person in the place is Rachel Donaldson, who on this Thursday afternoon, just before happy hour, bellies up to the oak bar that she helped build for the latest permanent exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Industry, “The Neighborhood Corner Bar,” which opened to the public this past October.

“Everything you see here is an artifact,” says Donaldson, the museum’s new curator, with the exception of the brass-railed bar top, which is a prop hand-built by volunteer John Reuter.

The “Corner Bar” exhibit was Donaldson’s first big project upon arriving at the BMI in 2022. The New York native and former College of Charleston professor comes to the museum with an extensive background in labor and working-class history—both areas of study that are deeply entwined in the iconic corner bars of Baltimore.

“These spaces were a lot more than just drinking establishments,” says Donaldson, who focuses on the period of 1870 to 1920—essentially the Industrial Revolution until Prohibition. “This was a time when bars were referred to as workingman’s clubs. They were third spaces that did a lot for working-class notions of community and masculinity.”

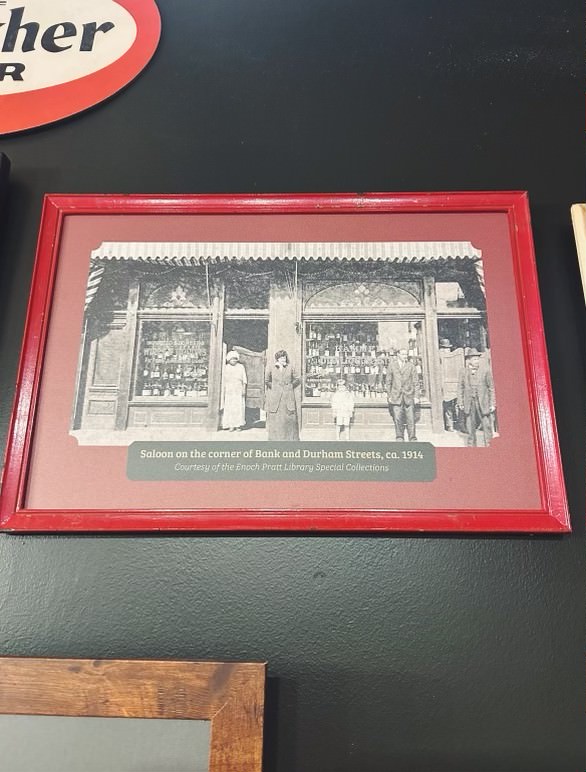

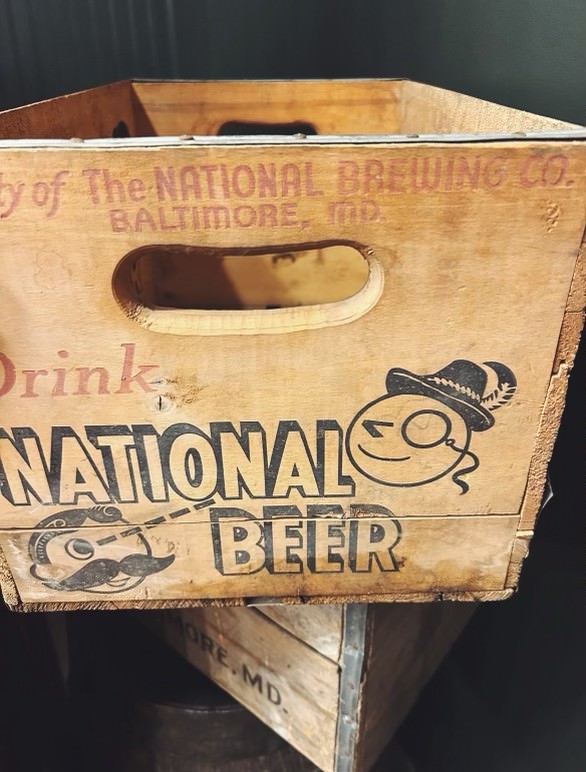

Back then, these men’s-only saloons were vital social hubs. Often sponsored by one of the city’s number of booming breweries—American, Globe, Monument, National—they had surprisingly refined digs, usually featuring a long standing-room bar where waterfront, railroad, and factory workers could find solace from poor housing conditions, 14 hours a day year-round. With the purchase of a five-cent house beer, patrons got a free lunch, the local newspapers, access to public bathrooms and telephones, conversation about sports and politics, and general camaraderie. Babe Ruth’s family owned a few of these bars. H.L. Mencken was a regular.

“These bars were often talked about as being the most democratic spaces, because you didn’t have to be wealthy, you didn’t have to pay dues—and for the white, male working-class, they were,” says Donaldson, noting that the local brewing industry was bolstered by an influx of German immigrants. “But if you were a person of color, you would not have been accepted,” with Black neighborhoods opening their own juke joints instead.

While the exhibit explores the communal and cultural identity fostered in these early bars, it also touches on their inequities. Women were often permitted inside, but only through the side “ladies entrance,” like the faded rust-red example hanging on the museum’s right wall. During the lunch hour, when boiled eggs, coddies, and bologna sandwiches were on offer, they could eat in the backroom, and after work, they could pick up to-go growlers to drink at home with other women while watching the children.

For her research, Donaldson dug through the BMI archives, interviewed multi-generation bar owners, and collected whatever materials she could from the community. Scholarship on bar history is limited, and many of these original spaces were destroyed in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, with even more shuttering during Prohibition.

But a few still stand, mostly with new names, though still bearing old details—the wooden bars, the side doors, the Natty Boh on offer. Now, there’s also Orioles on the TV, Utz above the cash register, a whole range of beer options, and, at their best, a broader, more inclusive clientele, seeking the same sense of belonging.

“We had no idea how popular this exhibit was going to be,” says Donaldson. “It’s tapping into something, and I don’t know exactly what. But personally, I love being a regular. I love going in and seeing the same people and being recognized. If someone knows your order, it’s this connection, not just to the wider community, but to your neighborhood, and to your place.”