Arts & Culture

Telling the Whole Story

Museums and historic homes enrich the present by grappling with their own difficult pasts.

W alking through the halls of the Homewood Museum on the Johns Hopkins University Campus, there are reminders of its genteel former residents, the Carroll family, everywhere. Dignified portraits hang in front of intricately patterned wallpaper, and fine china is laid out in a sunny dining room, as if waiting for a multi-course supper. But turn a corner toward the butler’s pantry and you’ll come across a small alcove, a lone table, two chairs, and a low bed taking up most of the floor space. Presiding over the room is a dark, featureless mannequin in red and green livery. His portrait doesn’t hang anywhere in the house, but this faceless figure is meant to represent one of the other long-time residents of Homewood, William Ross.

Ross, his wife, Rebecca, and their two children were domestic servants in the Carroll house. Along with the Conner family, they made up a portion of the slave population at this historic Baltimore mansion throughout the early 19th century. They lived there, they worked there, and though their stories were long ignored in favor of architectural details and explanations of the Carrolls’ role in the foundations of Maryland, new research and programming from Hopkins has brought their lives to the forefront for the very first time.

Like many at historic estates across the country, the stewards of Homewood have spent recent years grappling with the harder parts of their building’s history. These homes offer windows into the past, but that past is by no means spotless. Slavery, indentured servitude, and the oppression of less privileged populations are embedded in their stately halls. But changes in education and expectations of visitors, as well as recognition by museums that they have a moral and ethical responsibility to tell the whole story, are altering these spaces for the better, and historical interpretation—the process by which historians describe, analyze, evaluate, and create an explanation of past events—is evolving.

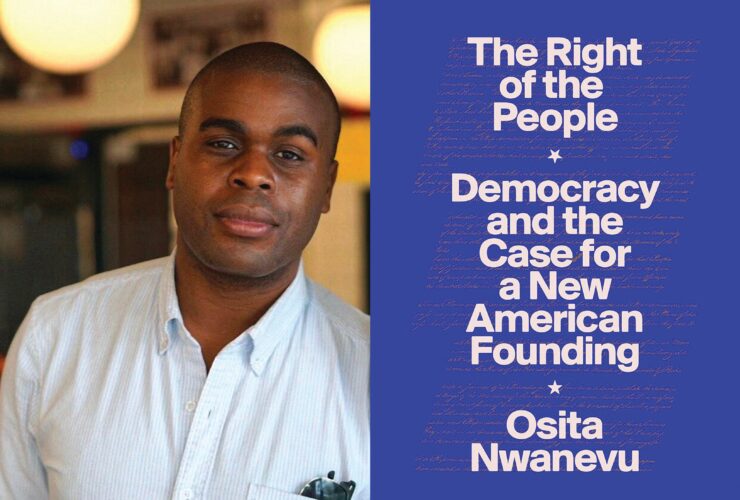

Can't Miss Fall Arts Events for 2019

Round out your fall arts experience with film, literature, exhibits, theater, music, and more.

M useums across the country have spent the past few decades wrestling with how best to address cultural traumas and connect with people whose histories have been ignored. Since 1999, the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience has been expanding its network of historic sites and cultural institutions that “connect past struggles to today’s movements for human rights” and “turn memory into action.” Included on the list are sites such as Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and James Madison’s Montpelier, both of which historically excluded slavery narratives from their programming, but today have dedicated themselves to researching and sharing the lives of those enslaved populations with visitors. While the only site in Maryland with this designation, Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park, sits on the Eastern Shore, other places across the state are working toward the same mission: to tell more truthful stories and present more complete narratives to help visitors better learn the lessons from the past.

Julie Rose, director and curator of Homewood, has been asking how museums can best present what she calls “difficult history” since the 1990s, even writing a book, Interpreting Difficult History at Museums and Historic Sites, on the topic. Her focus crystalized in 1995, when she was tasked with developing new programming for reconstructed slave quarters at Magnolia Mound Plantation in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Changes in education and expectations of visitors . . . are altering these spaces for the better, and historical interpretation is evolving.

“One of my first assignments was to develop school programming and tours to use this new historic structure,” Rose says. “I said to [my director], ‘This sounds great. Where’s the research about the enslaved community at Magnolia Mound?’ She just looked at me and said, ‘Well, there is none.’”

It’s not an uncommon problem. While the lives of the prominent families who lived in these homes are often well-documented, the paths of those who labored on the estates are harder to track. The Walters Art Museum did not know the name of either of the enslaved women who worked at Hackerman House, now called 1 West Mount Vernon Place, until 2016, when students from the Baltimore School for the Arts brought to their attention a letter previously only known to nonprofit Baltimore Heritage. And up the road, the 11-person Hampton Ethnographic Team has spent nearly three years doing research and locating descendants of the hundreds of enslaved men and women who once lived on the estate at Hampton National Historic Site in Towson.

Dr. Cheryl LaRoche of the University of Maryland is partially responsible for this new, expanded look at Hampton’s history. Along with historian Patsy Fletcher, who has since passed away, LaRoche submitted a proposal to the National Park Service detailing their plan to research the descendants of the enslaved population at Hampton. Both had visited the site and found themselves disappointed by the lack of discussion of slavery at the Ridgely family estate, which could not have thrived without it.

“I took the grand tour and was told that some distance away were the slave quarters. We were not given a tour of them, but we went on our own, and that interpretation from many, many years ago never left me,” LaRoche says. “I was curious about the people who had been enslaved there and was frustrated by the fact that there had been no substantive discussion whatsoever.”

What began as a project to research the descendants of those freed when former Governor Charles Ridgely died in 1829 became much broader as LaRoche lobbied to extend the scope to include the estate’s entire enslaved population of around 800 people.

“That original interpretation would have continued the narrative of the benevolent governor who [freed] these 350 or so people,” she says. “And I think it would have reinforced this narrow discussion by only tracing back to the people who had been [freed]. In order to do a credible job, we really couldn’t narrow the interpretation to that select group.”

The results have stunned even LaRoche. When her research began, she told herself that if they managed to find 12 descendants, the project would be a rousing success. After all, in the 70 years that NPS had owned Hampton, not one had been found. Instead, they’ve traced hundreds through intense genealogical research, oral histories, and an expansion of previous research protocol. At a special presentation of some of the new narratives discovered at Hampton in October, LaRoche says the presenters had to explain to attendees time and time again that it was a one-time-only event and that the project itself was still ongoing. People were so moved by the stories that they were already asking when they could return or bring others back with them to hear more.

Although the research into these lost narratives is often incomplete, it offers much in the way of altering perspectives and shifting the conversations that visitors and educators have around these spaces. It can help reshape the way entire historic places are viewed.

The history of 1 West Mount Vernon Place inspired artist Roberto Lugo's ceramics for the reopened space's first exhibition.

F or years, Hackerman House was known primarily for its architecture and ceramics collection, but through the letter provided to them by BSA students, historians at The Walters learned of Sybby Grant, who was the cook at the house in the 1860s. While they’ve still yet to identify a second enslaved woman who worked in the home during that period, Grant’s story is now an integral part of the Mount Vernon mansion’s new life.

“From that moment, we realized that we actually could tell in a very concrete way stories about different kinds of individuals,” says Julia Marciari-Alexander, director of The Walters. “It created a sense of responsibility around the way that we use the interpretation of the materials that we have to think differently about the past and now—using these objects to create connections with people out in the community.”

For the first exhibition in 1 West Mount Vernon Place, which reopened in June 2018, The Walters commissioned ceramist Roberto to create pieces inspired by the museum’s collection, history, and occupants, including Grant. While the exhibition has since closed to make way for a new contemporary show (which will use Antonio McAfee’s interpretations of W.E.B. DuBois’ Exhibit of American Negroes and Jay Gould’s evocative portraits of modern-day Baltimoreans to explore class and labor across time), the museum acquired some of Lugo’s works, as well as the original Grant letter. Both are now on permanent display.

“This house had not been a home for a long time when we got it,” says Marciari-Alexander. “Returning to the notion of telling the story of the families who’ve lived here, the various workers who worked on the building, the two enslaved individuals who lived here . . . it’s been wonderful.”

At Hampton, the Ethnographic Team is in the process of editing their final report. While the research project officially ends this October, the many historic threads they’ve followed over the past two years will influence new programming at the national park for years to come.

“We’ve already been incorporating new information into our daily tours,” says Abbi Wicklein-Bayne, chief of interpretation for both Hampton and Fort McHenry. “But there will definitely be themes and stories that will be incorporated into everybody’s tour once [the study] wraps up, and we will be working on an exhibition.”

Farther south in Hollywood, Maryland, Sotterley Plantation recently hosted a remembrance day that included a public reading of the names of those who were enslaved there and a bell-ringing in honor of the men and women who died on the plantation, as well as on the journey across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa. The estate’s slave cabin, thought to be the only such structure in the state open to the public, opened in 2017 after an eight-year restoration project inspired by the work of Baltimorean Agnes Kane Callum, whose grandfather was born into slavery at Sotterley in 1860 and who began giving her own tours of the cabin to friends and family in the 1970s.

Of course, there is still far more work to be done. LaRoche notes that Maryland as a whole has been reluctant to engage with its difficult past. There is still no one place for families and historians to access plantation research across the state, and many of the historic homes where people could engage with this history have been converted into venues for weddings and other events, closing them off from the public. But steps can be taken to begin correcting that, too.

“There’s a whole field of study waiting to be opened up,” says LaRoche. “What you’re seeing with Homewood and Sotterley are individual efforts. They have not come together as a collective. We need to continue to do the type of research we’ve done at Hampton . . . and really make these associations look squarely at all the different aspects of slavery and labor to give the full context.”

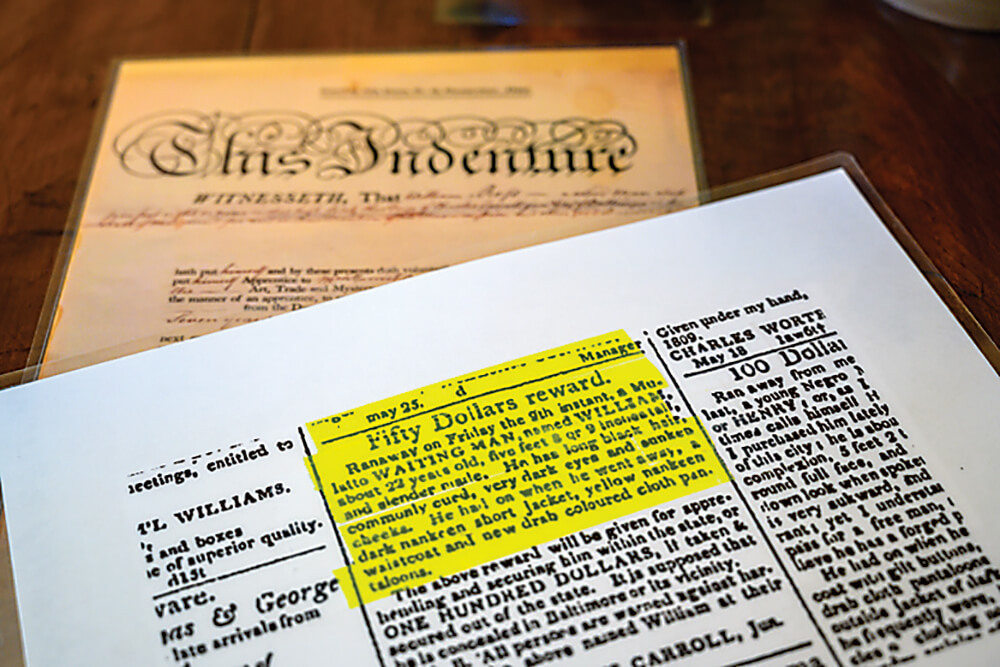

Copies of documents, including a posted reward for the return of William Ross and an indenture agreement, on view at Homewood.

A s this new research evolves these spaces and their exhibits, museum staff have also had to adapt. Many of those who give tours and engage directly with visitors are volunteers, and most are untrained in how to discuss cultural trauma or help people work through the intense feelings these new exhibitions can inspire.

Rose has already seen the change in visitor reactions at Homewood. While many are engaged and curious about the varied lives of those at the home, others have had more emotional responses. A visiting graduate student left the room during an anecdote about the life of Cis Conner, an enslaved woman who worked as a house servant and spinner for Harriet Chew Carroll. Conner bore six of her 13 children while living at Homewood and was eventually sent to a Louisiana sugar plantation with her husband, Izadod, and their family in 1836. While she and the children returned to the Carrolls’ plantation in Ellicott City in 1838, Izadod disappears from record after leaving Homewood. The student met with Rose in a hall to compose herself before moving through the rest of the tour.

“Her lower lip was sort of aquiver, and she was uncomfortable and she was unhappy,” Rose says. “I said, ‘What can I do?’ and we talked and I asked her, ‘Are you going to be okay?’ She said, ‘This is really important, don’t get me wrong. I know this information has to get out there. I just need to grapple with it.’”

The Butler’s Pantry at Homewood.

“One of the things that I’ve learned over time is that we can’t just give [staff] the stories, because [they] don’t know what to do,” says LaRoche. “Personal attitudes and ideas and understanding can cloud the research. So part of what we have to look at is truly the kind of comfort level people have with talking about slavery . . . and the willingness or unwillingness of the docent, the interpreter, to engage with the difficult history beyond this irresponsible narrative that has been perpetuated for so long. If we cannot begin to penetrate the psyche of the docent and the volunteer, we lose that effort.”

To that end, places such as Homewood and Hampton are actively training their volunteers and docents on how to have hard discussions with visitors and the best ways to present these stories to the many groups who pass through the museums, be they children on a school field trip or retirees revisiting a home they once toured purely to admire the silver. In July, Homewood received a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to bring in Linnea Grim, director of education and visitor programs at Monticello, and Shawn Halifax, who trained the frontline staff at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, to educate their staff.

“We really need to be sure that our docents feel confident that they have the tools to assist visitors in grappling with difficult history,” says Rose. “We’re a work in progress, because we continually need to learn not only the parts of history that we continue to uncover, but how to assist our visitors in learning.”

Hampton, too, is taking steps to better educate its staff, hosting a two-day training session this month that will cover both the new stories unearthed by the Ethnography Project and the art of interpreting tough subjects. They, like others, are preparing themselves to answer challenging questions and have hard conversations, ones that they should have been having all along.

“We continually need to learn not only the parts of history that we continue to uncover, but how to assist our visitors in learning.”

“To stand up as a docent and just give a lecture . . . it really doesn’t work for anybody anymore, because what [visitors] want is to have a conversation,” says Marciari-Alexander. “That’s what art has always been. It’s about conversation. It’s about standing in front of someone and sharing what you know and hearing what the other person knows.” The hope is that these conversations, these stories, these windows into long-forgotten lives, will help fill the gaps in our histories that past generations allowed to widen.

Untethered by its mission to any specific period, 1 West Mount Vernon Place is in a unique position as a repurposed historic home to explore meaning across history. Marciari-Alexander hopes to use it to challenge people to consider different points in time simultaneously and blend contemporary works with their historical inspirations. For now, in the same room where Sybby Grant once set plates around a table, McAffe’s ghostly, bust-like portraits from the 1900 Exhibition of American Negroes look out at the room as they seem to float in place, asking visitors to consider representation over centuries.

And even as tour groups loop through the halls of Homewood, some holding informational cards connecting them to a member of the Ross or Conner family, research is being done to lengthen their threads and connect them to the present. “The more you uncover, the more questions come up,” Rose says. “Many people ask about descendancy, so we have work to do. What happened to the next generations? Where are their descendants in Baltimore now? Maybe this will help bring them to light and maybe a descendant will contact us. It’s wishful thinking, but it would be so helpful.”