Arts & Culture

Baltimore Painter Documented ’70s and ’80s in Photorealism

Painter Jim Voshell quickly became a leading documentarian of the changing city.

After five years teaching art in Baltimore County Public Schools, Jim Voshell ditched the steady paycheck to paint full time, moving in 1971 into a former flophouse squeezed between the old Fish Market and police stables, near the still “thriving” red-light district known as The Block.

“A 90-foot room with 11-foot ceilings, $40 a month, and I fixed the plumbing and kitchen so I could live there,” the now 77-year-old Voshell says, smiling. “It was the perfect place for a working artist.”

“If you opened the windows on one side, the smell of fish hit you,” he recalls. “If you opened the windows on the other side, the stench of horse manure wafted in.”

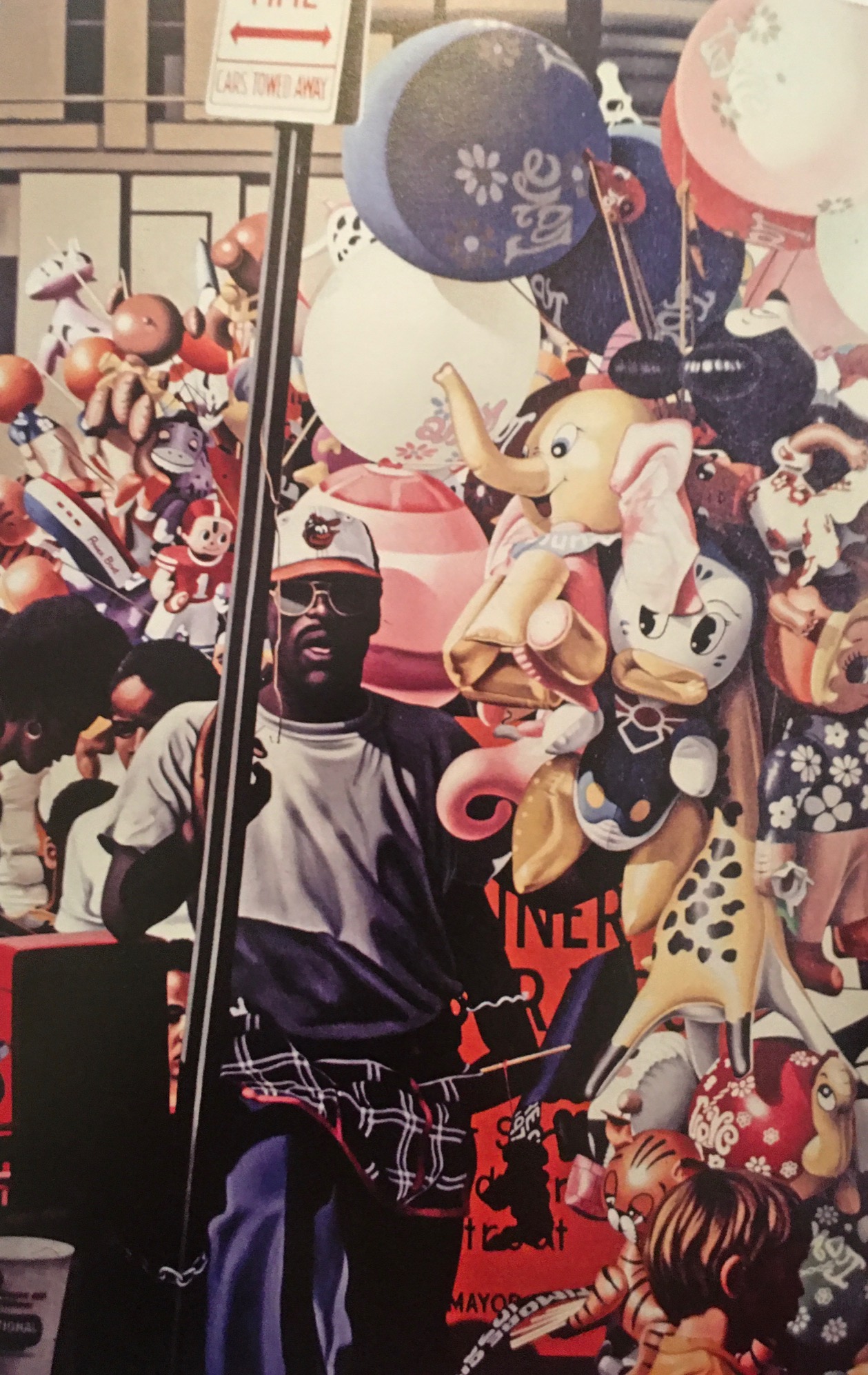

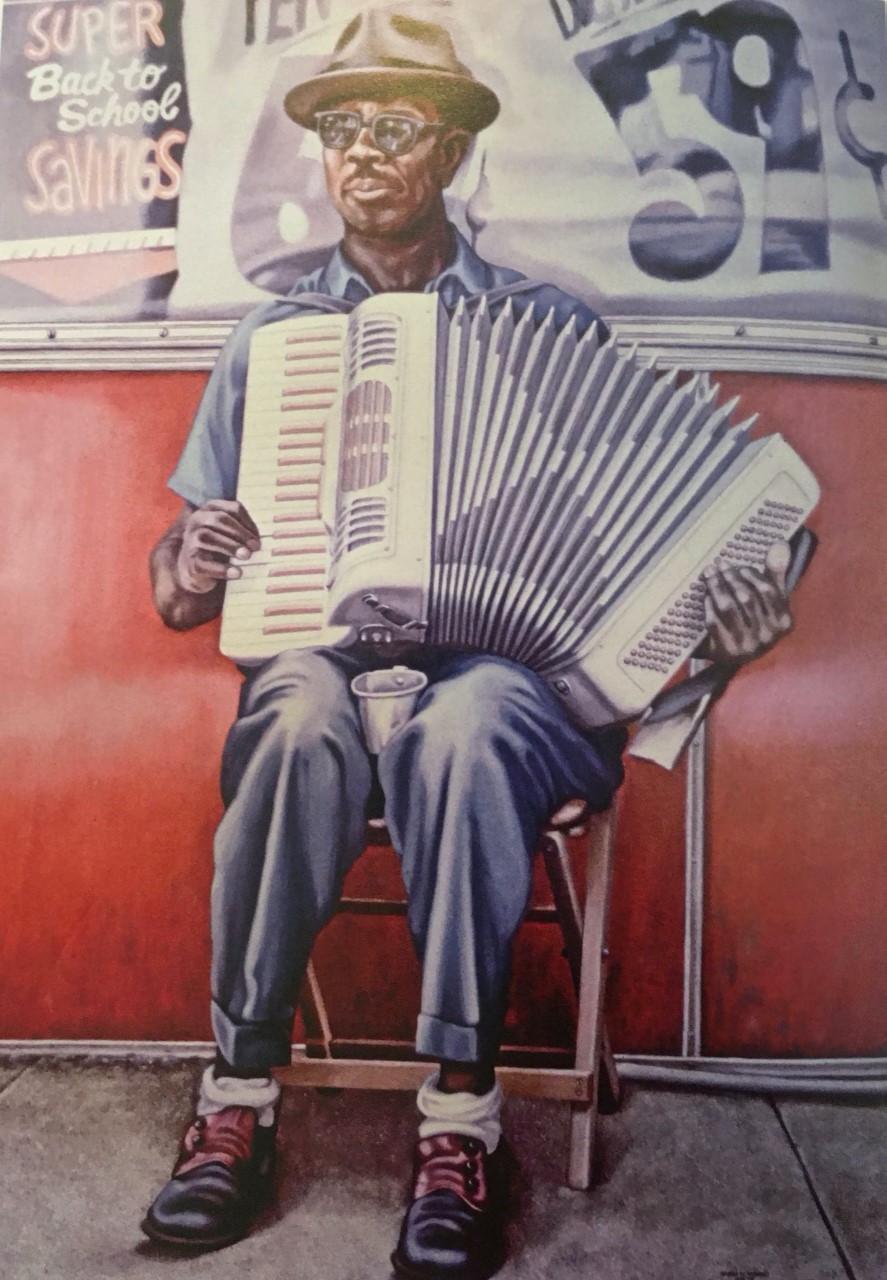

The bearded, burly, photorealistic painter from the Eastern Shore, who graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art, quickly emerged as a leading documentarian of the changing city. He painted street corners, sidewalks, and bus stops as he found them: full of arabbers, balloon vendors, strippers, alcoholics, fortune tellers, cops, trash, and, at least once, a dead rodent.

Capturing the 1970s in various stages of life and decay, he eventually had pieces exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Baltimore Museum of Art, and was one of the first artists selected by the then-new Baltimore Mural Program, which continues to this day.

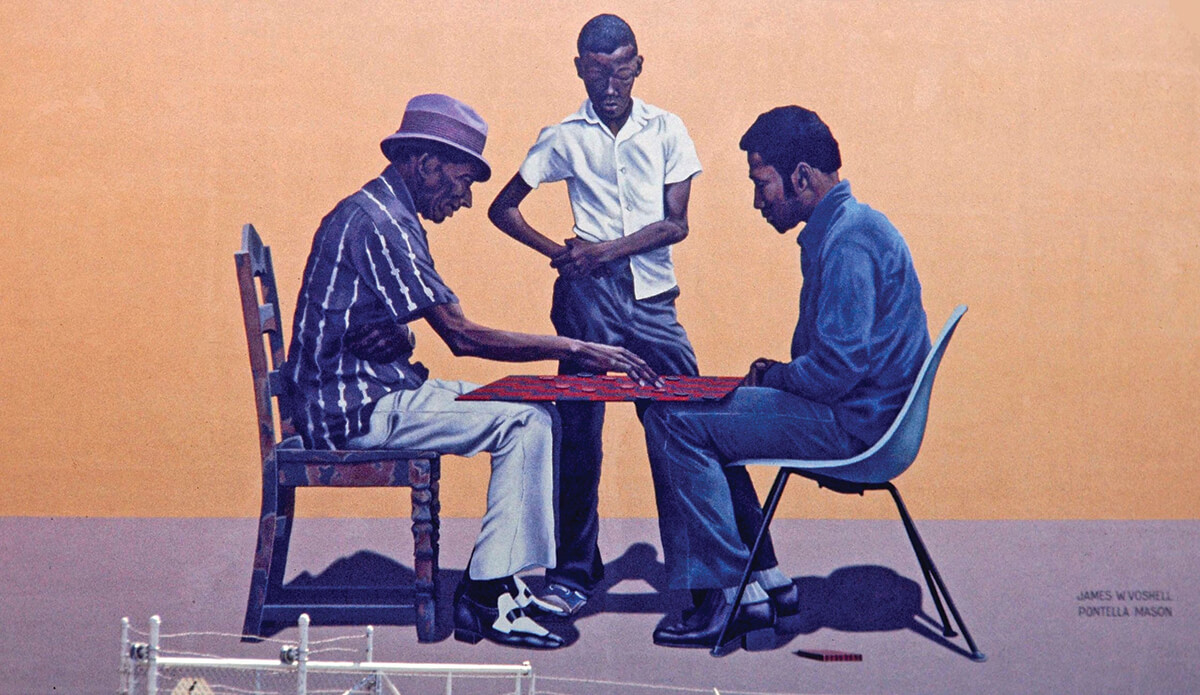

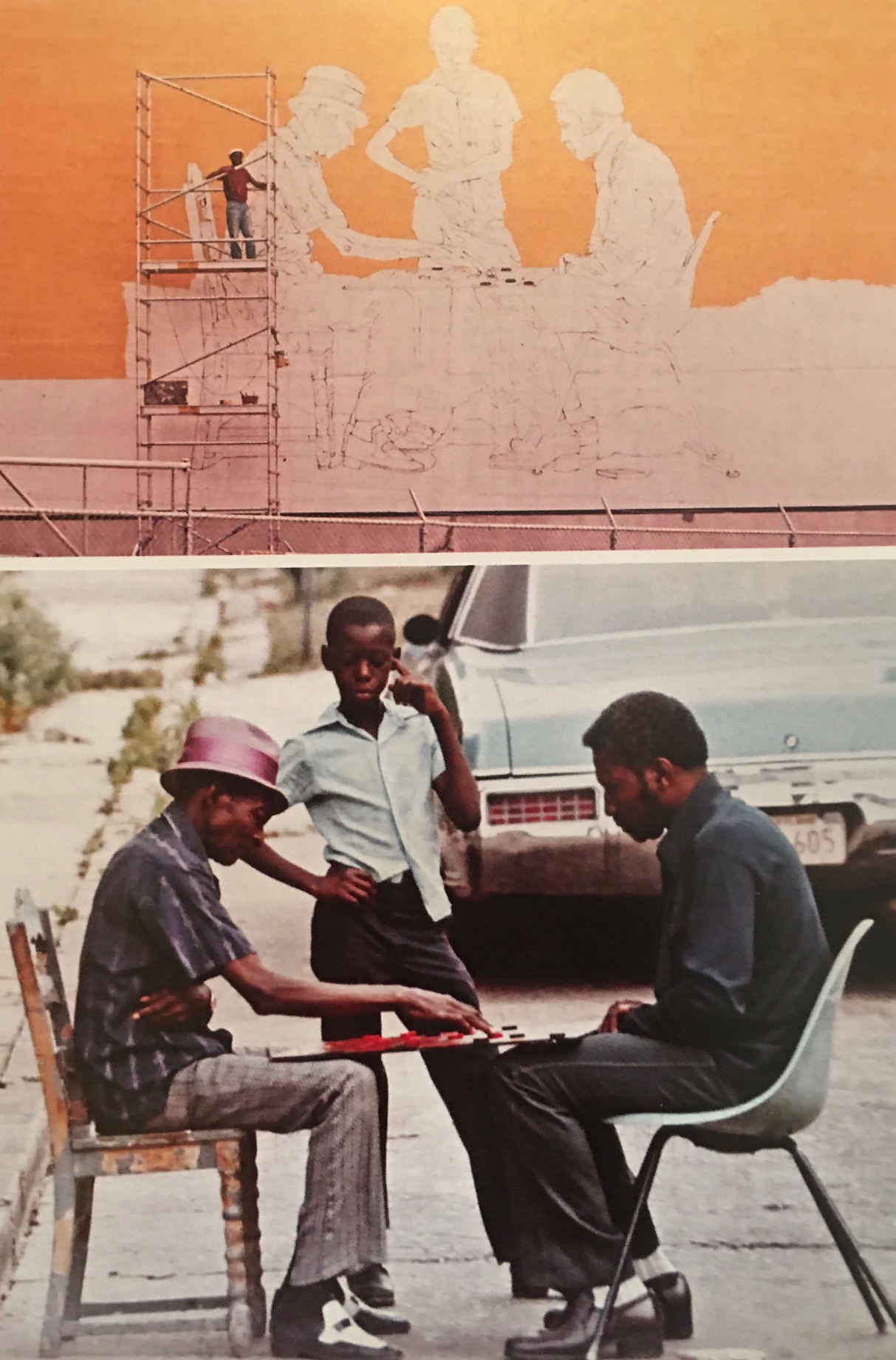

Voshell is probably best-remembered for some of those early public works, including a scene initially caught with his ever-present camera: the towering, three-story, 1975 mural of two men playing checkers (see above)—up for nearly three decades at the city’s Edmondson Avenue gateway—and a favorite of then-Mayor William Donald Schaefer.

Following the demolition of his downtown building, Voshell moved to a similarly gritty Frederick Avenue warehouse in Southwest Baltimore where he meticulously chronicled, with permission, and often gratitude from local residents, everything he encountered for another 22 years. (Oprah Winfrey, then with WJZ, once stopped by and shared a donut.)

“I always felt that realism had the widest bandwidth of viewers, consistently and unambiguously,” Voshell says of his affinity for that style. “I learned to paint with the sound of babies crying from open rowhouse windows and passersby shouting questions from the sidewalk.”

Two of his original street murals survive, if barely. One, another massive, three-story painting at Carrollton Ridge depicting neighborhood life there in a collection of oversized, Kodak-like snapshots, is largely covered with weeds and vines. The second, a commissioned football-field-length series of keys and locks, remains on the side of the EZ Storage facility on Reisterstown Road, but after 30 years, it’s fading.

In 1992, Voshell packed up for the last time, moving to a Parkton farmhouse owned by his life partner, Lynne Jones. After focusing on the concrete realities of urban life, he wanted to turn his attention to the complexity and beauty of nature, which he continues to do, despite diabetes, which has cost him several toes, and open-heart surgery last year.

“I grew up fishing and crabbing,” he says. “I always ‘saw’ the light on the water, the lines and groves in the tree bark. That never went away.”

This past August, Voshell and one of his former high school students, writer William Waters, collaborated on a 262-page hard-cover retrospective. Among the 200 images is the aforementioned rodent painting, titled “Dead Warrior,” which Voshell immortalized on a five-foot canvas in 1974. At the time, he was looking out from his Market Place studio when he witnessed a construction worker jump from his truck and beat a large rat to death with a board. Voshell ran down with his camera and then brought the lifeless rodent to his studio.

“It took a month to block out, draw, and paint. I included bits from the street, a beer tab that was nearby. I painted the pads on its feet, put some light on its toenails, added a hair at a time. My friends said, ‘You’ll never sell it.’”

Yet, during a three-day arts festival, a Johns Hopkins biologist kept inquiring, telling him he was either going to take a summer vacation or buy the painting. When the artist later delivered it to the scientist’s upscale apartment, the buyer hung it over his living-room sofa.

“It just shows you. The whole world doesn’t have to love your work. Or every painting,” Voshell says. “He had studied rats for 20 years in India. If one person likes it, that’s what matters in the end.”