Arts & Culture

Baltimore's Fascinating Relationship With Andy Warhol

The late artist's working-class roots and quirkiness mirror our city’s image.

Baltimoreans can feel some measure of pride visiting The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Located downtown in a renovated industrial warehouse—a “factory,” if you will—just a few miles from where Warhol grew up, the sprawling complex houses a gritty and glittering retrospective of his life, with some familiar artwork and Baltimore personalities in the mix.

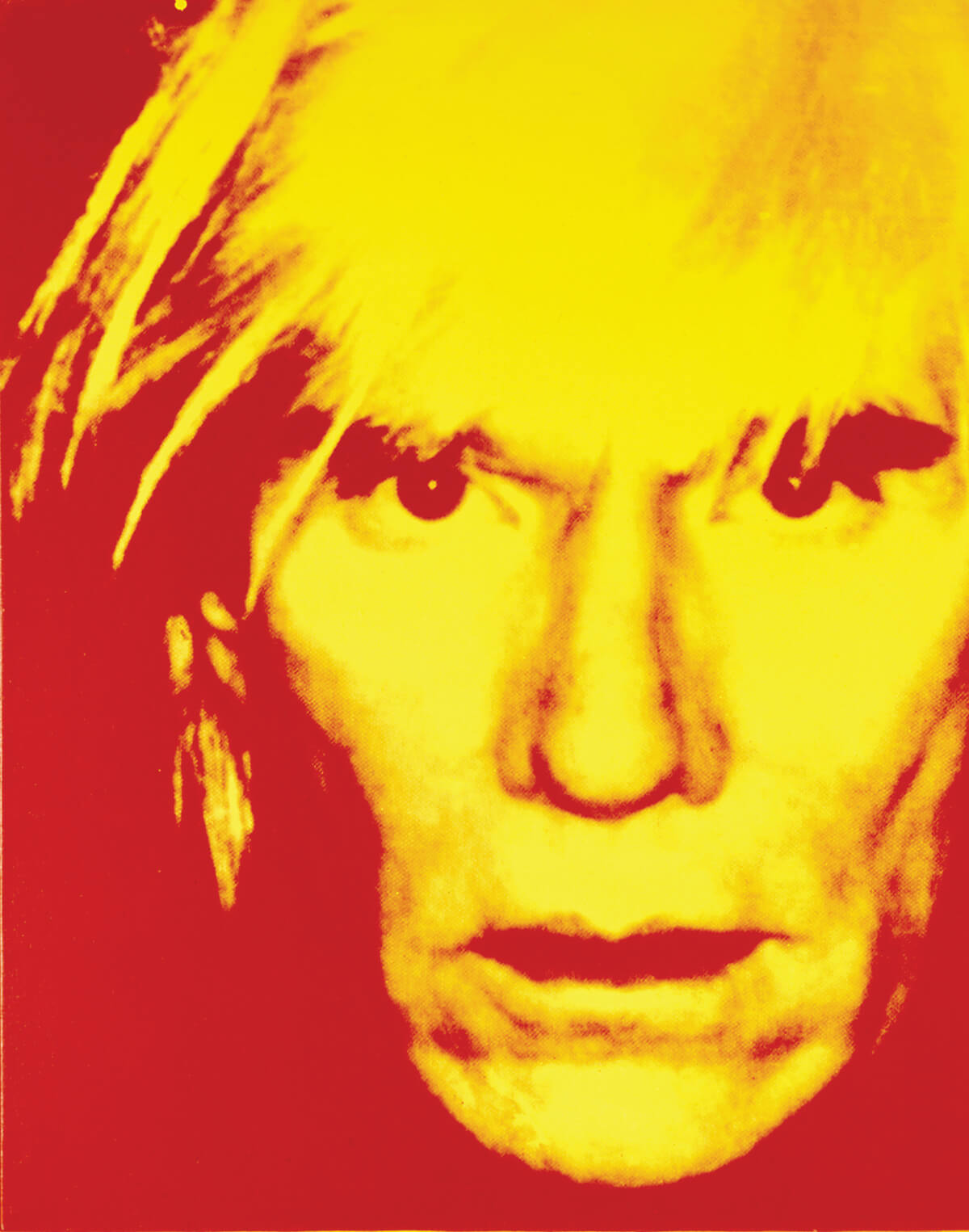

There’s a huge Last Supper canvas on view. And there’s a massive Camouflage painting and a “fright wig” Self-Portrait, too—just like at the BMA.

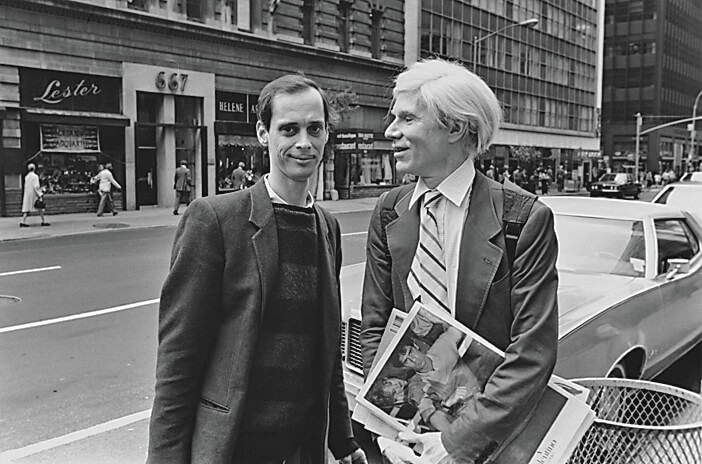

Standing at one of the 50 plus video monitors devoted to Warhol’s work, watching him create one of his signature pieces, you might notice that he’s listening to Billie Holiday as he paints; on another screen, he’s interviewing Frank Zappa’s kids, Dweezil and Moon; and on the most prominently displayed screen, there’s an interview Warhol did with John Waters, Divine, and Van Smith, the makeup artist who developed Divine’s distinctive look.

It’s a hoot listening to Waters tell Warhol about visiting the Enchanted Forest theme park and, in a Bawlmer accent, recall overhearing a mother tell a hilariously succinct summation of the Sleeping Beauty story to her children: “That’s Sleepin’ Beauty. She’s sleepin’.” The segment also includes film clips with locals such as Edith Massey and Jean Hill, and you can even buy Waters’s latest book (Role Models) and CD (A Date with John Waters) in the museum store.

“The Warhol [Museum] loves John Waters,” says the store’s clerk. “We like Baltimore, too; it seems like there’s a lot going on there.”

It’s particularly notable because Warhol has had a fascinating relationship with Baltimore, both during his lifetime and, especially, since his death in 1987.

Waters and Warhol were acquaintances, and without fanfare, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts—with Waters on its Board of Directors—has supported Baltimore arts groups with more than a million dollars in funding for exhibitions, publications, film festivals, and curatorial studies. There’s “a lot going on,” in part, because of Warhol money.

And the city has played a key role in enhancing Warhol’s legacy. The Baltimore Museum of Art has the world’s second largest collection of late-period Warhol works—topped only by The Warhol Museum—and Warhol is increasingly mentioned in the same breath as Matisse when discussing the BMA’s major collections. “Our Warhol pieces have become a signature holding for us,” says BMA contemporary curator Kristen Hileman. “And they’re growing in stature.”

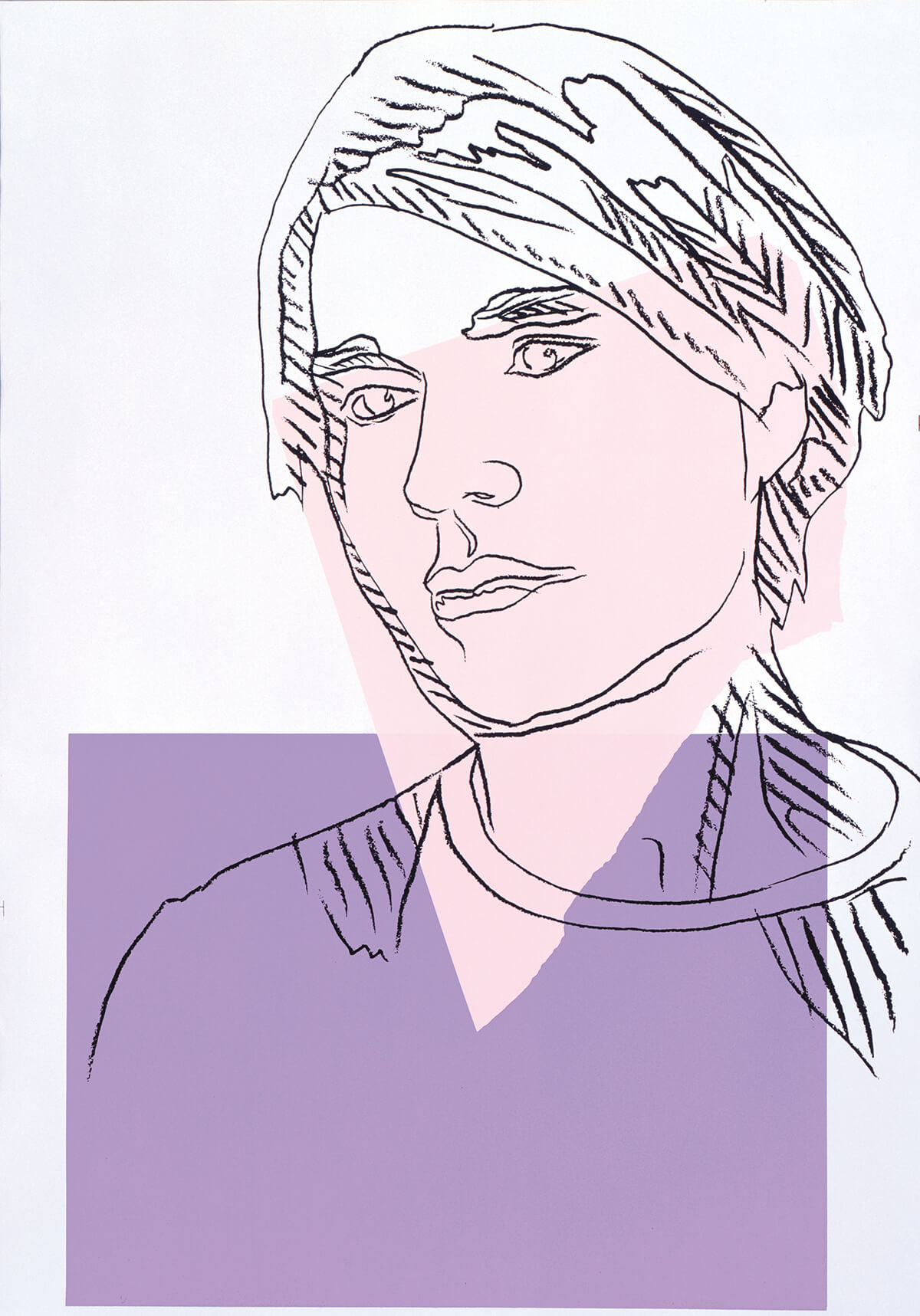

Now, a major traveling exhibition, Andy Warhol: The Last Decade, begins a long run at the BMA and figures to deepen the city’s relationship with the iconic artist. In fact, the BMA is a major lender to the show, which opens October 17 and closes in January 2011.

It seems that Baltimore’s relationship with Warhol has been fruitful and practically inevitable, given that his working-class roots and quirkiness mirror our city’s image.

But we haven’t always been so sure about courting Warhol. The BMA’s acquisition of Warhol paintings in the late-1980s/ early-1990s sparked controversy and even outrage at the time.

For years, critics have suspected that Warhol and his estate were scamming us and that his 15 minutes of fame would come to an abrupt end.

They were wrong.

Brenda Richardson is responsible for bringing Warhol to Baltimore. In fact, she literally brought him to town in 1975 for a now-legendary appearance at the BMA. Sitting in her art-filled living room near Cedarcroft, Richardson, who was at the BMA for 23 years, doesn’t waver a bit when assessing the importance of Warhol’s work. “Andy Warhol will always be huge,” she says. “He changed our world.”

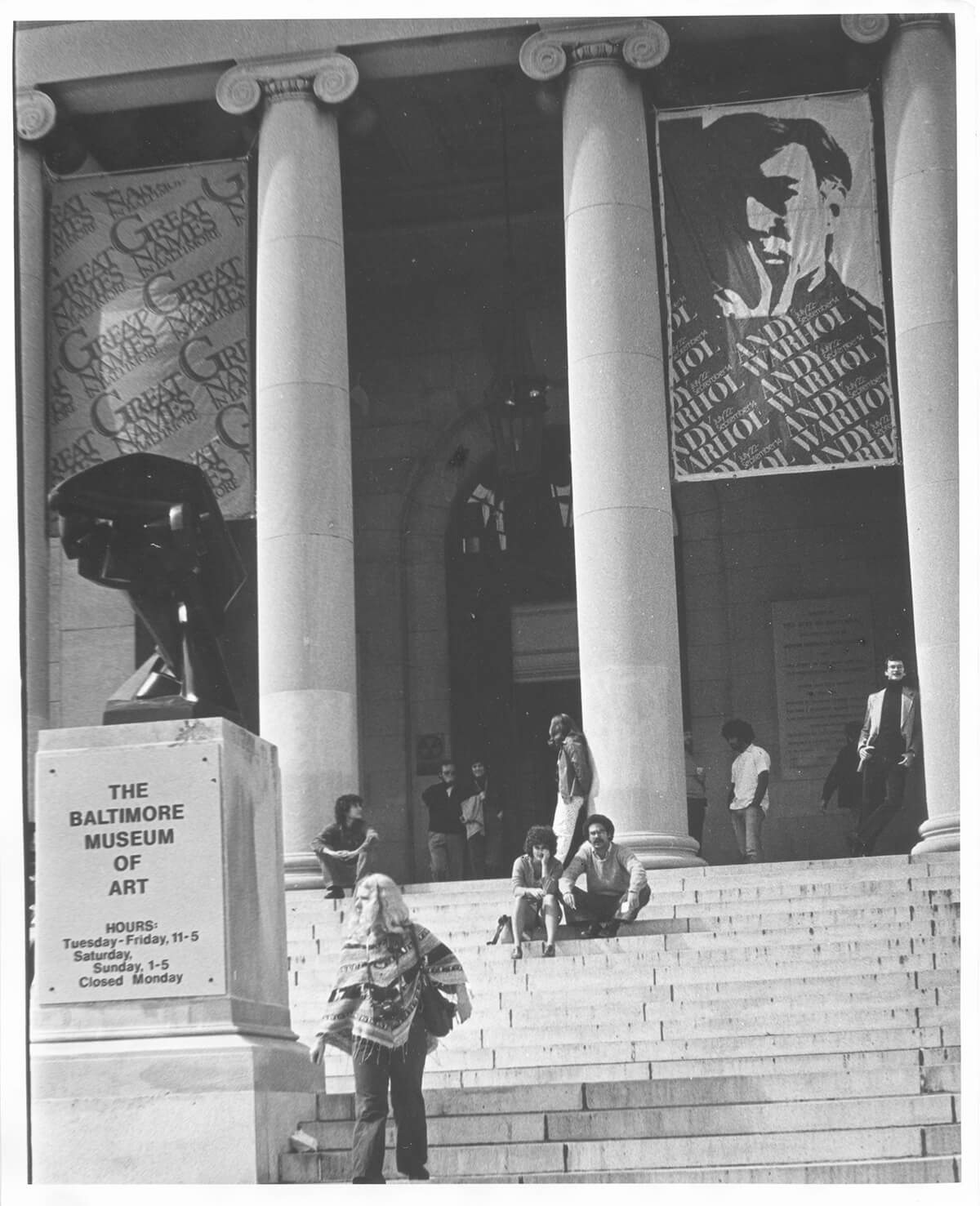

Richardson came to Baltimore from Berkeley University’s art museum in 1975, tasked with developing a contemporary art collection for the BMA. From the outset, she focused on Warhol and mounted a retrospective of his work, Andy Warhol: Paintings 1962-1975, during that first year. “Putting together that show, I went to lunch with Andy and Leo Castelli [Warhol’s art dealer] in New York,” she recalls. “Then, I selected the works for the show from Andy’s studio and Leo’s gallery, 40 paintings in all, and arranged for them to be brought to Baltimore—in one truck, if you can believe that.”

By that time, Warhol had revolutionized the art world, become a figurehead of the Pop Art movement, and cultivated his image as a sleek, international celebrity. His 1962 paintings of Campbell’s soup cans and silkscreened portraits of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley redefined what was considered fine art, and his production methods—working with a bevy of assistants—rattled critics and raised even more questions about his validity. And Warhol’s jet-setting lifestyle often drew more attention than the art itself. Still, his art and influence were everywhere.

A BMA press release by Alice Steinbach—director of public information at the time, she later wrote for The Sun and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1985—noted that “this major exhibition will offer Baltimoreans their first chance to see all the famous Warhol ‘Pop’ paintings (soup cans, Liz Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, etc.), which have filtered down into the mainstream of everyday life. . . .”

Baltimoreans weren’t particularly impressed. The show included one of Warhol’s large Mao portraits, and dozens of BMA members cancelled their memberships in protest. “To my shock and amazement,” says Richardson, “they claimed we were Communists.”

The press wasn’t much kinder. The Sun called Warhol “boring” and “old news,” while The Columbia Flier referred to him as “a humorless, self-contained freak.” They didn’t think much of the paintings, either.

There was a similar reaction after Richardson and the BMA acquired Warhol’s later work after his death. When the museum bought The Last Supper for $682,000—the most it had ever paid for a single work of art—in 1989, “all hell broke loose,” recalls Richardson.

Comprised of two silkscreened images of Leonardo’s painting, the piece was religious in subject matter, massive in size—six-and-a-half feet high and 25-and-a-half feet long—and tinted yellow, or “puke green” as John Waters describes it.

“People howled about it,” says Waters, himself a BMA trustee in the 1990s. “Everybody flipped out.”

City Paper called it a “dubious transaction” and a “massive con job,” pointing out that it cost more than $4,000 per square foot. The Sun asked museum-goers their opinions: “I don’t see the point,” “it’s awful,” and “it’s phony” were among the responses. The museum was inundated with letters and phone calls from community leaders, clergy, and others who considered the painting sacrilegious.

Still, Richardson and Arnold Lehman, then director of the BMA, remained certain that it was, as Lehman notes today, “a great prize for the museum.” So they made special arrangements for the doubters to visit the BMA, view the painting, and hear Richardson talk about it. “I just told the truth,” she says. “With Andy Warhol, it’s so easy—the guy is such a heartbreaker. He’s an overwhelmingly emotional person himself, who puts it all out there in his work, contrary to public opinion.”

Richardson seems moved, as she speaks: “I talked about yellow being the color of betrayal and what it means to be betrayed. I asked them to look into their own lives and think about the times they’ve had any kind of personal betrayal, with a spouse or a friend, and what that means in human terms. I talked about Andy and the fact that he had almost certainly felt betrayed by members of his entourage at various points. And I told them that Andy wasn’t making fun of their beliefs, because he was a believer, too. They were surprised to learn that he was a devout Catholic and went to Mass with his mother every week.”

Richardson says that, in the end, “it seemed like everyone was persuaded.”

“Once people heard Brenda talk about it,” says Waters, “they shut up.”

WARHOL’S LATE WORK WAS LARGELY DISMISSED BY CRITICS AND RARELY SHOWN DURING HIS LIFETIME.

Five years later, Richardson was at it again. The BMA had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to acquire more paintings, when The Warhol Foundation—established in Warhol’s will for “the advancement of the visual arts”—offered select museums a chance to buy his work for 50 percent of its appraised value (as determined by Christie’s).

The offer was good for just 18 months. “It was an extraordinary moment for museums to purchase work they normally couldn’t afford,” says Vincent Fremont, a founding director of the Foundation and currently its sales agent for paintings, drawings, and sculpture. “Andy’s work was very undervalued, and by 1994, the prices still weren’t all that expensive.”

Richardson and Lehman leapt at the chance to acquire a body of work for the BMA’s New Wing for Modern Art, which was set to open later that year. With the early paintings—the soup cans and Marilyns and such—sure to bring top dollar, they focused on late work that was largely dismissed by critics and rarely shown during Warhol’s lifetime.

They put together a proposal, secured funding from a pair of donors—Laura Burrows-Jackson and Richard Pearlstone—wooed the Board of Trustees (winning key support from Chairman James Riepe), and bought 15 paintings and three drawings in all. The haul included the massive Camouflage, Hearts, and Physiological Diagram paintings, two Oxidation pieces (which Warhol created by applying urine to metallic paint), the “fright wig” Self-Portrait, and drawings of The Last Supper.

“I started with the Self-Portrait, which was absolutely essential, and built around that,” says Richardson. “I was thinking about education and was determined to show our audience that Andy had a heart, that this was really personal stuff and not rubber-stamped. I got multiples of some things to show the variations.”

“It turns out Baltimore made the biggest purchase,” says Fremont, “and they made really excellent choices. Brenda knew what she was doing.”

But others weren’t so sure. There were rumblings around town that, once again, Warhol had pulled one over on us. Although a sum was never disclosed, the price tag was rumored to be as high as $1 million.

A Sun profile of Richardson written five months after the purchase speculated ominously that her decisions “aren’t always in the best interests of Baltimore.”

The one example given was “buying 18 works by Andy Warhol.”

As it turns out, the Warhol purchases were visionary, as their skyrocketing value and critical reappraisal attest. In 1987, The New York Times was calling Warhol’s late paintings “shallow” and “self-plagiarizing.” Eleven years later, a Times reviewer found them so “slight” that “you could pass them by without a thought.”

This summer, The Times changed its tune when reviewing The Last Decade exhibition during its run at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, where Arnold Lehman is now director. This time around, the reviewer found Warhol’s late work “ravishing,” “magnificent,” and “mind-boggling” and concluded that “Warhol made some of his best paintings during these years.”

Similarly, The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl, as recently as 2000, was dismissing the late work and claiming, “Warhol’s great moment was brief. Caught in the feedback of his own influence, he declined rapidly as an artist.”

In an August 2010 review of The Last Decade, Schjeldahl acknowledged that “anything negative you say, or even think, about Andy Warhol as an artist may come back to humble you,” noting that he had previously “discounted the late styles of [Warhol’s] painting . . . as the phoned-in flailings of a tired talent.”

He then lauded the exhibition’s “array of potent visual inspirations, grandly realized,” praised Warhol’s “heroic abstract art” and “marvels of color,” and concluded that the late work “stands up to the strongest art made by anyone else, anywhere, at the time.”

He ended with this blunt directive: “See it. Admit it.”

The dollar value of the late work has escalated in accordance with the critical reevaluation. Vincent Fremont notes that Warhol’s paintings of dollar signs, which he could “barely sell” in the early-1980s, now go for “a million and a half.” He also says that a Rorschach painting, like the one purchased by the BMA, sold for under $100,000 in the mid-1990s and sells for $2 million today. And in May, a “fright wig” Self-Portrait similar to the one owned by the BMA sold at Sotheby’s for $32.6 million.

AS IT TURNS OUT, THE BMA’S WARHOL PURCHASES WERE VISIONARY.

So what happened? Why the drastic change? It’s increasingly apparent that Warhol anticipated many contemporary images and trends, reality TV and celebrity worship among them. His 1968 declaration, “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes,” became prophetic in the age of YouTube and Facebook.

“It’s not unusual for a great artist’s work to be dismissed for many years after their death,” says Fremont. “But people finally come around.”

It’s a bittersweet reality for Richardson—now working as a freelance arts writer and independent curator—who tried unsuccessfully to organize traveling exhibitions of the late work in 1993 and 2000. “As time goes by, more and more people realize how important he is,” she says. “It’s just beyond question.”

“A whole discourse of probing into deeper meanings has developed around his work,” says the BMA’s Kristen Hileman. “He’s a pivot point in talking about trends in contemporary art and culture, because he sets the stage for future artists.”

Hileman, who’s in the process of reconfiguring the BMA’s Contemporary Wing, stresses that “the Warhols will continue to have a very central place in the galleries and in our collection.”

And Warhol figures to play an important role in the arts scene overall. Some observers speculate that the Warhol Foundation has, traditionally, been more inclined to send funding our way, because of the BMA’s long association with the artist.

Since the Foundation was established in 1987, Baltimore has received more than $1 million in Warhol funding—more than any city of comparable size, including Denver and Seattle. In the past year, The Contemporary Museum and Maryland Art Place have each received upwards of $100,000, while the Creative Alliance and American Visionary Art Museum have gotten $75,000 in the past few years.

Does the Foundation look favorably on the city, because of its Warhol holdings? James Bewley, the Warhol Foundation’s program officer, says it “has no bearing on our grant making.” He instead lauds the city for its “impressive range of artistic activity” and “arts organizations that support experimental and risk-taking work.”

But some think otherwise. “They would have to,” figures Lehman. “They all know Baltimore, because we established a wonderful relationship with the Foundation. And they love Brenda.”

“We made a pretty large commitment to Warhol,” says Richardson. “I have no doubt that the Warhol Foundation would look favorably upon a city that made such a statement.”

“I think Baltimore would be looked upon very positively, and it obviously has been,” says Fremont, noting that he doesn’t speak on behalf of the Foundation.

Either way, Baltimore is fortunate to have embraced Warhol to the extent we have, and The Last Decade exhibition drives home the point that his 15 minutes won’t be expiring any time soon.

See it. Admit it.