Arts & Culture

The Day The Music Died

Independent music venues fight for their lives.

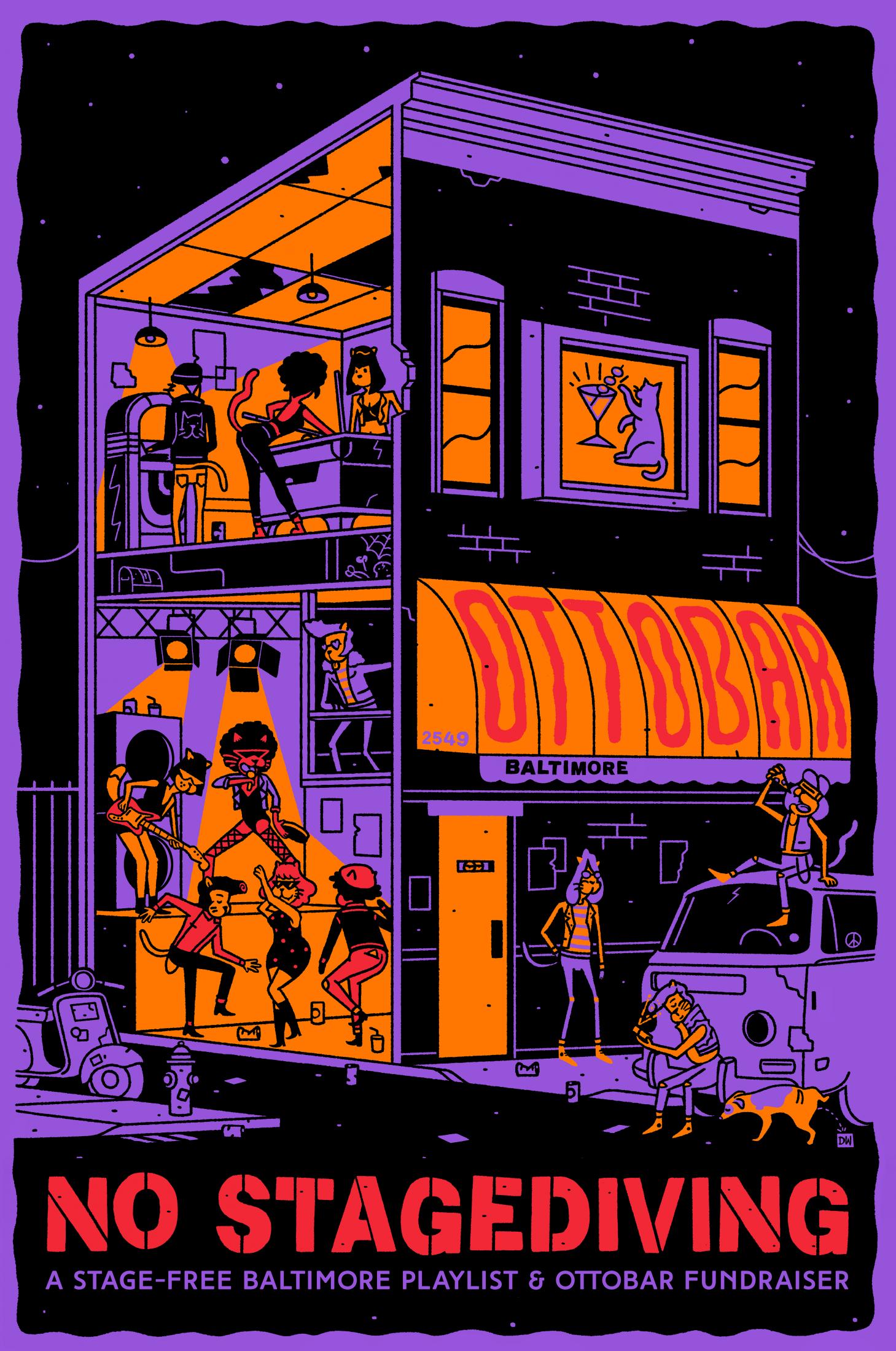

Last spring, a collective sigh of relief spread throughout the Baltimore music community when it was announced that the Ottobar, the beloved, rough-and-tumble rock club in Remington and a local institution for the past two decades, would be purchased by its longtime bar manager, Tecla Tesnau.

Just six months earlier, it went up for sale, leaving fans of all ages wondering what it would mean for the city’s cultural landscape if that small black room and dimly lit dance floor was no longer packed with sweaty bodies. Or worse, if the graffitied walls were painted over to become just another slick venue without the same gritty heart and soul.

Behind the bar since its inception downtown on Davis Street, Tesnau had seen the Ottobar through many changes over the past 23 years, from the digitization of the music industry to the gentrification of Baltimore—none of which would prepare her, of course, for what would arrive six months after she took over, when the novel coronavirus swept around the world and left a sea of shuttered concert halls in its wake.

“After I got handed the keys, we were running full tilt, 100 miles per hour, setting records left and right, the lineup was absolutely stellar—even my accountant at one point was like, ‘Good work, kid,’ which is high praise from someone who is usually all about the books,” says Tesnau on a Tuesday afternoon in late September. “Then, boom, COVID landed, and we hit an absolute cinderblock wall. We got knocked on our ass.”

Since early March, the Ottobar stage has stood mostly empty. No crowds have gathered beneath its sparkling disco ball. No feet have dangled from the second-floor balcony. No lines have wrapped out the door, down the alleyway, and around the corner onto Howard Street. The bar is tidy, the barstools tucked in, not a drop of liquor spilled on the floor beneath them for months.

Shortly after the first case of COVID-19 arrived in Maryland, Governor Larry Hogan announced restrictions on public gatherings, first limiting groups to 250 people—half of the Ottobar’s capacity—then 50, then 10, before a statewide lockdown. For most venues, the weeks that followed meant navigating the quagmire of canceled concerts, refunded ticket sales, unemployment applications, and gathering paperwork for the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program.

“We were literally building the airplane as we were flying it, and are still continuing to do so,” says Tesnau. “The space feels so different now. It smells better, for one—I’ve taken to cleaning it a lot. But it’s cavernous, absolutely cavernous. I can’t tell you how much I miss having music in there. Honestly, if I had known that last show was going to be our last, I would’ve been in the mosh pit, too.”

Much like restaurants, the very existence of music venues—particularly small, independent clubs that don’t have the parent companies or shareholders of those in cahoots with conglomerates like Live Nation and AEG—was upended this year as, overnight, their entire business model became virtually obsolete.

Suddenly, COVID-19 made concert-going as we know it simply unsafe, with the virus spread through respiratory droplets, be it coughing or singing, plus close proximity and indoor environments increasing the risk of transmission. Tours were called off, and venues became some of the first businesses to close.

“No one knew then what extreme toll the virus was going to take on the music industry at large,” says Tesnau. “It has absolutely decimated and devastated the music industry. And it’s this massive trickle down.”

“A lot of people don’t realize how many people work in this industry,” says Abigail Janssens, owner of The 8×10 in Federal Hill. “It goes from the artists to the bus drivers who drive them to the tractor trailers who carry the equipment to the people who load the stage to the sound engineers, the light technicians, the box-office person, the security, the bartenders. It takes many, many people to put on a show.” (Not to mention that for every $1 spent on a ticket at independent venues, an estimated $12 is generated within local economies on restaurants, hotels, transportation, and retail.)

Janssens and her husband, Brian Shupe, took over their tiny Cross Street stage in 2005, breathing new life into the live music staple that dates back to the 1980s, when it hosted the likes of Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers before they were famous. The couple added multi-night residencies and cemented the venue as a hidden gem for both local and national rock-spectrum talent. Their last show was on March 12, the same day that Governor Hogan announced his first restrictions, causing them to cancel the final round of the Charm City Bluegrass Festival’s Battle of the Bands the next evening.

“We’ve been closed ever since,” says Janssens, who called off some 100 shows through September. “Our space is so small. There’s almost no way to socially distance, and I’d be devastated if anybody came in and got sick or spread the virus to other people. No way did I think we were going to be shut down for more than a couple weeks, a few months at most.”

“NO WAY DID I THINK WE’D BE SHUT DOWN FOR MORE THAN A FEW MONTHS AT MOST.”

It has now been nine months since her staff was laid off, joining the millions of Americans who went on unemployment this year due to COVID-19. And although she received the PPP and took out a small-business loan, she has still had to take another job in order to keep the lights on at The 8×10, which was already an uphill battle prior to the pandemic, as it is for many independent club owners.

“We’re definitely not in a business to become millionaires,” says Janssens. “It’s very, very tough. There are fans that come and go, there are bands that move on from a small venue—which is great for them. Being closed, we still have to pay $12,000 a month just for bills: rent, insurance, utilities, and all the other things that go along with owning a business. Now we’re almost out of the money from our loan, and it’s starting to get scary.”

The coming months will be critical for these clubs, with cold weather forcing the world back indoors, and spiking COVID-19 cases causing cities and states to clamp down again. It is estimated that 90 percent of independent venues will close permanently within the next few months without financial help from the federal government, according to the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA), a recently established advocacy group. They are currently lobbying Congress to pass the Save Our Stages Act, which would establish a $10-billion grant program for this portion of the industry.

Locally, Governor Hogan announced state-wide emergency funding for live entertainment venues in late October, with grants up to $500,000. But even with this vital aid, without a vaccine distributed widely in the near future, and with Maryland once again in a state of emergency, the situation remains precarious.

“I feel terrible for some venues who are struggling to decide whether they should get out now or wait,” says Janssens. “Luckily, we’ve been in business for 15 years. We have good credit and were able to secure a loan. Otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to make it either. I’m saying this hoping to be open by next spring at the latest. If it goes on longer than that, then we might be in trouble.”

So far, no Baltimore venues have announced permanent closure, but the two-year-old Soundry shuttered in Columbia in July, and the decade-old U Street Music Hall went dark in D.C. in October. Several spaces, like Joe Squared, a live music respite for 15 years on North Avenue, and The Sidebar, a veteran punk club around the corner from City Hall, remain temporarily closed. As does Rituals, a DIY newcomer that opened just last summer in the former Windup Space, whose owner, Émile Weeks, described the waiting game as “moving through stages of grief.”

“Seeing so many clubs teetering on the brink of bankruptcy breaks your heart,” says Sam Sessa, Baltimore music coordinator at WTMD. “These spaces are part of what makes Baltimore’s music scene one of the best in the nation. Their loss would be a huge blow.”

Without ticket sales, not to mention food and drink—an important source of revenue for many venues—some have been able to stay afloat through alternative outlets. The Crown in Station North has shifted operations into its secondary restaurant space downstairs, with the club’s bouncer, Tony MacDonald, still checking IDs, but now also temperatures. The Ottobar, with its alleyway patio, and the Creative Alliance, with its roving Sidewalk Serenades, were able to utilize the outdoors during warm weather.

Others have tried their hands at smaller indoor concerts as Maryland entered new stages of its coronavirus recovery plan this fall. At press time, however, Baltimore City has just reverted to Phase One, with venues now allowed to operate at only 25 percent capacity, including staff. This creates an economic pickle for smaller spaces who have to decide if those numbers make any financial sense.

“Fifty people doesn’t even begin to pay a band, and is it worth it for my bartenders to come in and possibly get sick for nothing that they’re used to making?” says Janssens, whose 8×10 typically holds 250 people.

“It’s going to help us maintain, but it’s still a very big challenge to keep hanging on,” says Adam Savage, music manager at Baltimore Soundstage, which launched limited-seating concerts at its downtown venue that typically holds 1,000 people. He also works at the Metro Gallery in Station North, which has remained closed since March, as it’s difficult to social distance in a 240-person room.

Still, it is uncertain whether or not audiences will even feel comfortable coming back inside. The Keystone Korner in Harbor East and Cat’s Eye Pub in Fells Point have already had some initial success—and Ticketmaster is now toying with the idea of verifying COVID test results and vaccination statuses before admittance to shows in 2021, which may be the way of the future—but for the time being, it’s not for everyone. “It’s unfortunate, but I don’t think people feel comfortable, and I don’t feel comfortable having a band on our stage, and I don’t think that’s going to change anytime soon,” says Tesnau.

For that, there has been a sort of second digital renaissance within the industry. Several years back, albums moved onto the internet, forever changing the way we consume music. Now, artists themselves have shifted to social media, with virtual concerts becoming the new way for performers big and small to reach fans in the comforts of their own homes.

Every Tuesday since late March, singer-songwriter Cris Jacobs has taken to Facebook Live for at-home concerts, accepting online tips to support his family and out-of-work band and crew. Rapper DDm and indie-rockers Future Islands also released new records via video performances, while dozens of jazz and classical artists, like Warren Wolf and Lafayette Gilchrist, have beamed out sets via YouTube through Mount Vernon’s An Die Musik. And audiences are tuning in, not just in Baltimore, but from across the globe.

“There’s definitely a democratization that’s happened to performance during this pandemic, which is wonderful—we’re all competing for the same eyeballs,” says Josh Kohn, performance director at the Creative Alliance, whose Virtual Front Row livestream series, featuring local artists such as Lea Gilmore and Super City, has evolved into a hybrid in-person offering. “But it leaves the question: what is the role of a venue right now, when you can’t put people in a room together?”

“WHAT IS THE ROLE OF A VENUE WHEN YOU CAN’T PUT PEOPLE IN A ROOM TOGETHER?”

It also raises the question of longevity. Artists and venues are making investments into livestream technologies, like better sound and camera equipment, but most acknowledge the reality of screen fatigue, perhaps due in part to an increasingly technology-tied world in quarantine. Even more likely, it’s because online performances miss something harder to grasp or define—that kinetic electricity of a tiny room reverberating with sound.

“There’s just this vibration during a live performance that you can’t replicate in any other way,” says Kohn. “There’s an energy and a magic when something powerful happens in front of a group of people together. Personally, I came to the Creative Alliance because I love that room. I really miss it.”

Of course, the absence of venues has also had an immense impact on the musicians themselves, who use these stages to not only make a living but also hone their craft and feed off the exchange with a live audience.

“I’m used to it now, but the first few weeks, there was just silence after I played a song, which was really strange,” Cris Jacobs told us this summer. “Playing [virtual] shows made me realize just how much I do miss live music. It’s what I’ve done for so long. Until it’s gone, you maybe don’t realize all the ways it served you, and everybody.”

In recent years, one venue in particular, The Crown, has become a pivotal proving ground for a diverse array of DIY artists, with the small blue room and main red room serving as stepping stones to bigger clubs. This is where Abdu Ali started their iconic Kahlon parties back in 2013 that helped put Baltimore’s music scene on the map and launch the avant-garde rapper on a trajectory toward indie stardom.

“So many young, new artists come through there—it’s really one of the last underground venues in America, as gentrification has hit cities so hard so that places like The Crown literally cannot exist,” says Ali, who also tips their hat to Metro Gallery and mentions the important work that more venues need to do to nurture marginalized creatives. “It’s very important for artists to have the comfort of knowing they have a space where they can do their thing in their city, in their community, in their own backyard.”

For now, for the foreseeable future, most music venues will stay closed, as many states shut down, and the reopening of businesses remaining a point of national debate. In last-ditch efforts to buy more time, the Ottobar and 8×10 launched GoFundMe campaigns this fall, receiving an outpouring of community support, and perhaps a glimmer of hope.

“There is still a huge hunger for live music in people’s lives,” says Savage, who helped Soundstage put on drive-in concerts at the Frederick Fairgrounds this summer. “We’ve been gathering around drums in caves since the very beginning. Live music is part of human existence. It’s something we need on an absolute fundamental level. It just can’t go away.”