Arts & Culture

Diner: An Oral History

Thirty years after its release, Baltimore gives its most famous film the respect it deserves.

Earlier this year, when Vanity Fair marked the 30th anniversary of Diner by proclaiming the Baltimore-set movie, written and directed by native son Barry Levinson, “the most influential movie of the last 30 years,” it led to lots of head-scratching: “Not E.T., not Reservoir Dogs, not Titanic, but . . . Diner?”

Well, yes. By using pop-culture-driven small talk to create rich characters rather than advance the plot, this little 1982 film about nothing paved the way for everything from Seinfeld and The Office to Pulp Fiction and Superbad. Filmmakers and authors from Judd Apatow to Nick Hornby have lined up to declare their adoration.

And while Baltimore, portrayed so lovingly in the film, would like to say it always knew Diner’s greatness, local test audiences hated it and The Baltimore Sun gave it a terrible review. Thanks to Baltimore, Diner almost didn’t make it into theaters.

We talked to Levinson, producer Mark Johnson, cast members Kevin Bacon, Steve Guttenberg, and Paul Reiser, and others, to compile a definitive history of the film, its origins, its secrets, and its legacy, including plans for a Broadway musical with music by Sheryl Crow. (Yes, really!)

Barry Levinson, director: Diner happened by accident. I worked with Mel Brooks on his movie High Anxiety. I used to tell Mel some Diner-esque stories, and he said, “You should write that as a screenplay,” but I never really followed up on it because I couldn’t figure out what the hell it was about.

I wrote And Justice for All . . . with [ex-wife] Valerie Curtin, and then we did another couple movies together. She was also an actress, and she went off to be in some film. I had some time, and I sat down, and suddenly I wrote “Diner” at the top of the page, and three weeks later, I finished it. When Valerie went away, I thought, “Oh, it’s all about male-female relationships, lack of relationships, lack of communication.”

Mark Johnson, executive producer: I met Barry when I was the assistant director trainee on High Anxiety and Barry was one of the four writers. We struck up a friendship. I didn’t know anything would ever come of it.

Barry was immediately likeable. Not a big, outgoing person, but he clearly liked to laugh and was friendly. It’s not easy to work with Mel Brooks—because he’s hard to compete with—and Barry somehow stood out. There seemed to be a lot more going on with him than you were first led to believe.

Levinson: I was always at the [Hilltop Diner in Northwest Baltimore]. Some of those conversations in the movie came right out of conversations I had at the diner. The argument about Sinatra and Mathis and who you make out to, and the influence of Presley used to come up.

The big fallacy is that the guys in the movie were really the guys in the diner. I put people together, mixed them up. I took things from my cousin, Eddie, from other friends, and they became composites for the characters. Boogie might’ve been the closest in that he was a hairdresser, he did get involved in bets, he dressed differently. Eddie and Shrevie and Billy and Modell are all put together from different people.

“The studio didn’t like it. They wanted it to be one of those screw-around movies. they wanted it to be Porky’s.” -Mark Johnson

Johnson: I started working for Jerry Weintraub at MGM, and Barry was writing Diner. I loved Diner when I read it. And that’s why it’s so universal: I didn’t know these characters. I hadn’t grown up in Baltimore. I’m not Jewish, and yet I understood these characters. I understood them as guys hanging out, but I understood, more importantly, what they were all sort of hungry for.

As soon as he had a script, I gave it to Weintraub, and he set it up almost immediately at MGM. We were very low-budget. The good news was that MGM had a lot of higher-profile movies at the time, and they kind of left us alone. At $5 million, they weren’t worried about it.

For casting, we used Ellen Chenoweth, who was just starting her career. Now she’s a big deal: She casts the Coen brothers movies and several Clint Eastwood movies.

Levinson: I think I saw about 600 guys. And that was before you taped people, so you just met them. You know what you want to get, to a degree, but you want to be open enough to see what some actors bring to it.

Kevin Bacon, Fenwick: I had been on Guiding Light for a year, and I had just been offered another year, and that’s tempting when you’ve been out of work or working as a waiter for so much of your life. But it just didn’t feel right to me, and, even though I had no prospects, I quit the show. A week later, I got a call to audition for Diner, and it was like a message from the gods.

It was a massive call. They said I could read for any part, so I chose Billy because he was romantic and got the girls, and Boogie ’cause he was cool. Barry said go back out and read for Fenwick. It wasn’t something I related to, but I did it, and I got a call back.

In the callback, I was really sick, like 103 fever, but I had to go in—I’m sorry if I made anybody else ill. I had a slowed down, out-of-it quality, just based on the illness, that sorta worked for the character, and, in a funny way, I held onto that for the movie.

Levinson: Paul Reiser came with a friend, not there to audition—not even an actor—but Ellen saw him and started talking to him and said, “You oughta see this guy.” He came in, and I met him, and I cast him.

Paul Reiser, Modell: It was a very serendipitous accident that I happened to walk in with a buddy. They actually came to New York to look at comics, and, even then, I wasn’t included in the group. But, for some reason, they flagged me.

The thing that always amuses me is that it was so in the wheelhouse of what my comedy was. I had just started taking acting classes, and I was eager to show my great depth and range, and Barry kept saying, “You don’t have to work that hard.” I said, “Well, if I don’t, it just sounds like guys having coffee in a diner.” And he said, “Yeah, that’s exactly what I’m looking for.”

Levinson: Mickey [Rourke] came in, and I liked him. It just took some time to sort it out in my head, because, of course, he’s going to be different than the real Boogie—you’re not trying to do the real Boogie, you’re just trying to find the essence of a character that you respond to. It was very key, because he becomes a real dominant character, and you want an actor that can step up to that.

Steve Guttenberg, Eddie: I met Jerry Weintraub, Barry Levinson, and Mark Johnson at Weintraub’s offices and we had some nice discussions about the script and the character. It was thrilling because Jerry and Barry and Mark were all really, really good at what they did. Barry described Eddie as a little hard-headed and independent, liked to live with and stay close to the family and the old friends. He was a good character.

Levinson: I only saw one person for the role of Beth and that was Ellen Barkin.

Johnson: At some point, Ellen, Barry, and I just knew we had the right cast. There was no doubt. The more we worked the cast, the more we knew we had the right people.

Reiser: It was literally my first job. I had never been in anything. Johnson still teases me, cause I didn’t know anything. I was like, “So, what, do I take a bus to the set?” “No, you idiot, we got a guy and a truck.” “Oh, I didn’t know that, that’s awfully sweet.”

Johnson: I remember we were a big deal. There had not been a lot of movies shot in Baltimore. The city couldn’t have been nicer.

Levinson: We shot mostly nights. I remember coming back, daylight is coming up, and you’re coming back to the Holiday Inn to go to sleep at. Everybody else is getting up to go to work. Baltimore is now beginning a day, and you’re finally calling it a night.

Reiser: I fondly recall the off hours—shooting and coming home at six in the morning, just being in this bizarre world that underlined the absurdity of the whole thing. We were all, for the first time, away, out of the comfort of New York, in a period piece, and you’re literally 12 hours off from the universe.

I remember waking up for the first day of production at the Holiday Inn and looking down at the parking lot, and there were all these beautiful vintage cars. And I remember thinking, “Wow, I’m in a real movie and I have a character name, and one of those cars is my car.” And I get down there and they’re like, “Uh, no, you don’t have a car.”

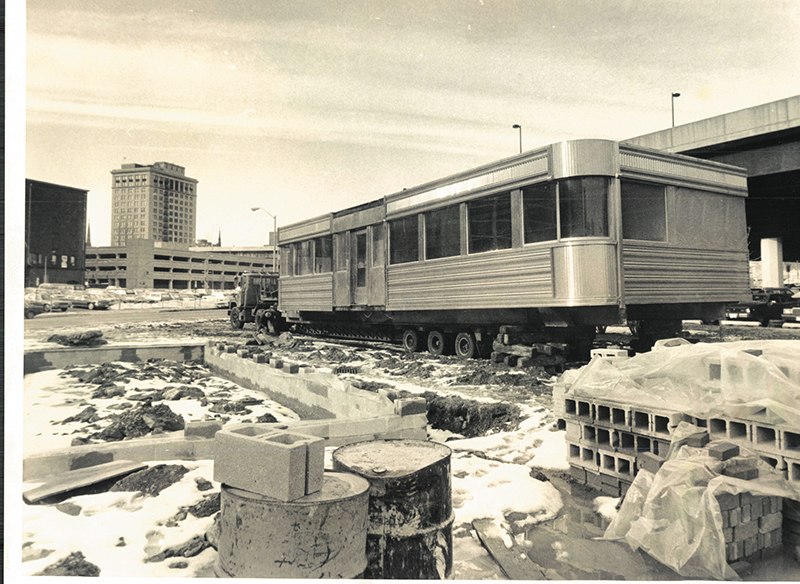

Johnson: We had trouble finding, of all things, the diner itself. One of my big pre-production coups was finding the perfect diner in New Jersey and trucking it down and planting it where we wanted it to be.

Levinson: We were trying to use the Double T Diner on Route 40, and we kept getting into this negotiation: They wanted more and more money, and I said, “Look, we don’t have it, it’s a cheap movie.” They said, “Yeah, but it’s an MGM movie.” I said, “It’s a cheap MGM movie.” And they just pushed us and pushed us and we couldn’t do it.

I was riding around with the cinematographer, Peter Sova, in Fells Point, and we came upon this piece of land with the Domino Sugars sign in the background across the harbor, and I said, “Wouldn’t it be great if a diner sat there?” I told Mark. We found a diner graveyard in Jersey. We went up there, found a diner, put it on a flatbed truck, brought it to Baltimore, and put it there.

The Baltimore Sun review pointed out “[the real diner guys] probably didn’t go to the ‘Fells Point Diner’.” The reason I called it ‘Fells Point’ is because we shot it in Fells Point—that looked nice! Does it matter that they were at the Hilltop Diner? This isn’t some historical piece. It looked interesting.

Johnson: Baltimore’s an amazing city. made up of these distinct neighborhoods. I remember Barry telling me it wasn’t until the sixth or seventh grade that he realized being Jewish was a minority. Where he lived, in the Northwest, everybody was Jewish.

I introduced Barry years ago to John Waters, and they each started talking about their Baltimore, and I realized neither one had been in the other’s Baltimore. Where Barry and his gang hung out had nothing to do with where John was.

The funny thing about Baltimore is, all of these people tell me they used to go the real diner and hang out. If it’s all true, it must’ve been the size of Memorial Stadium.

“We all looked different, but we were the same in a certain way.” -Steve Guttenberg

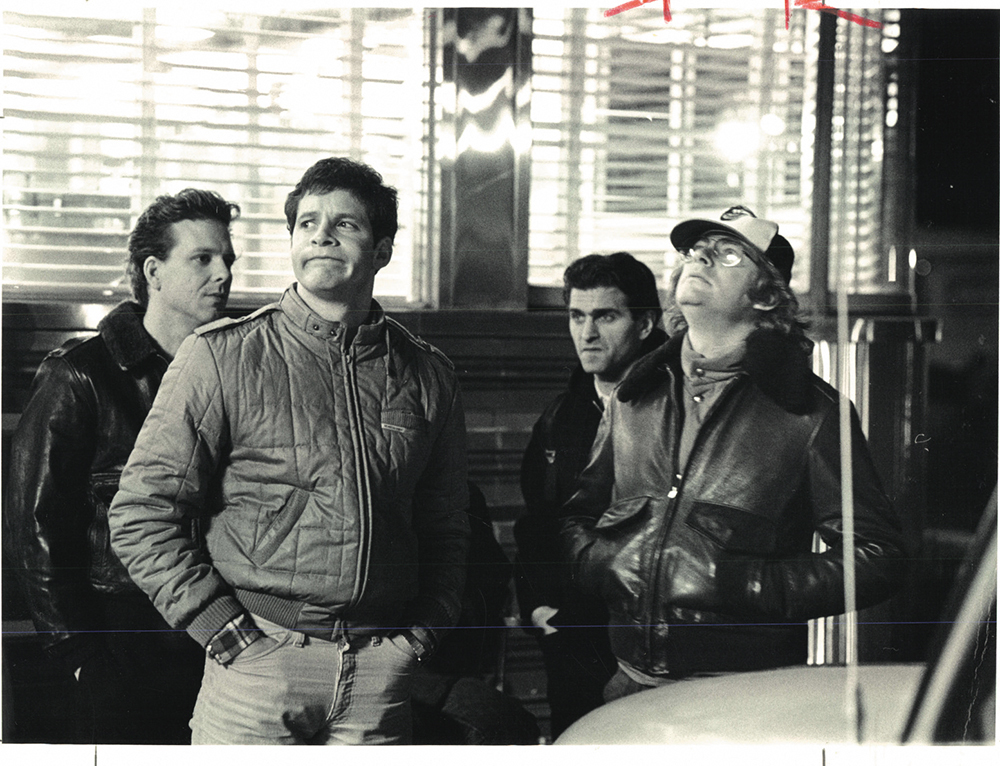

Levinson: I thought, “Why don’t I shoot all the diner stuff last, so at least they’ve gone through as much time as they can spend together to get as close as they can.”

Guttenberg: Barry had done films before and he understood that you can use a film’s schedule to your advantage, and he did.

What makes a hit movie is a cast, when everybody just connects. We all looked different, but we were the same in a certain way. When you’re acting with people like that, you really enjoy it. All those moments become not just a moment in a movie, but a moment in your life, and you remember it.

Reiser: Barry has such confidence. It’s actually astounding, looking back now, as his first film [as a director]—how clear he was on what he wanted and how to get it. He told me from the beginning, “We’re gonna make your part bigger.” I said, “Okay, whatever. I’m happy to be in a motion picture.”

Levinson: I intentionally underwrote Modell. He was the sixth guy, kind of the outsider and he was connected the closest to Eddie, so I thought, “I’ll play around. I just need a guy who can deliver, who has a motor.” When I stumbled onto Paul, I thought, “He can do that.” Between takes, I would talk to him, and he would fiddle around with it.

Reiser: I remember when we shot the “nuance” scene, me driving with Mickey. Barry said to me, “You’re bothered by the word ‘nuance.’” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I don’t know, it’s a strange word, just play with it.”

The “roast beef” scene with Guttenberg (“Are you gonna finish that?”) was totally ad-libbed, and it’s possible we were doing it off-camera. We were just sitting there. It was late, but they would feed us what we wanted. I remember we had done the scene, and it didn’t dawn on me that it was of any value. Later that night, we were shooting the leaving-the-diner scene and Barry pulls me over and says, “Ask Eddie for a ride home, like the time you were asking him for a roast-beef sandwich.” I said, “Is he gonna give me one?” He says, “I don’t know. Let’s see.”

Barry’s brilliance was knowing there was comedy there. I certainly didn’t know it. He probably told Guttenberg, “Reiser’s gonna ask you for a ride. Make him sweat it out a little.” And that was the extent of the scene.

“You have to be incredibly close to these people incredibly quickly.” -Kevin Bacon

Levinson: Mickey and Guttenberg really got along, and they came up to me and said they wanted to do a scene together because they didn’t have one, so I wrote a little scene for them, which is the scene where Eddie’s talking about being “a virgin—technically.”

Guttenberg: I liked Mickey a lot. We became really close. We went out to clubs together, we had good times. We said to Barry, “We’re the only guys who don’t have a scene together.” He went back to his trailer and a few minutes later, he said “What do you think of this?” We said, “This is great! Let’s shoot it now!” and we did.

Mickey was brilliant, ending the scene by pouring sugar into his mouth—stole the f—ing scene. It was magic to watch that mother f—er. We’re still in touch. He’s a good boy.

Johnson: Mickey Rourke was the next big thing, he was going to be DeNiro. He had a cool about him. I found out after we did the movie that Mickey used to go to Guttenberg’s room and help him with his lines. Mickey didn’t want anybody to know because it made him seem like too much of a good guy.

Reiser: Shooting those diner scenes is what I remember most, because it was last, and it was the most intense. For the last week, there was this “camaraderie camper,” where they literally shoved us in the same hamster cage when we weren’t shooting. It did what it was meant to do: We got closer, we got a little riskier with our jokes. We were cutting close to the bone, busting each other’s chops. And there was some friction of people just being a little too close to other people’s faces, which is what happens with friends.

It was in those diner scenes that it finally felt really comfortable, and it really confirmed that we were in somebody’s hands who knew what he was doing.

Bacon: You get thrown into this situation where you have to be incredibly close to these people incredibly quickly. For whatever reason, we were able to do that.

For a long time, those relationships sustained. I remained very close with Tim [Daly] and Paul for a long time. You’re talking about only 7 or 8 weeks of shooting, and we developed really strong friendships.

Johnson: We wrapped the movie after 42 days and Barry and I were on a plane back from Baltimore. We looked at each other and said, “It is what we set out to do.” We had this sense of satisfaction that two young filmmakers pulled off what we wanted to.

It was dispiriting when we showed it to family and friends, and got very little enthusiasm. It’s one thing if you’re not sure what you got, but we said, “Maybe we’re the only two people who like this movie.”

The studio didn’t like it. They wanted it to be one of those screw-around movies. They wanted it to be Porky’s—those crazy kids in Baltimore driving around, trying to get drunk and laid. And it wasn’t that at all.

Levinson: After we made it, the studio looked at it and had a heart attack. It wasn’t a coming-of-age movie like they thought it was.

I remember meeting with a studio executive after he saw the movie and he said, “You have a lot to learn about editing.” I said, “I’m sure I do. Give me an example.” He brought up the roast-beef sandwich scene. “Well you’re going on and on with, ‘Are you gonna eat the sandwich, not eat the sandwich,’ just cut it and get on with the story.” I said, “Well, that is the story.”

It’s a way to talk about friendship. A lot of time you see movies and people say, “How long have we been friends?” Friends don’t talk about being friends. From the nature of their conversation, you know they’re friends. That was the point. We talk about problems with girlfriends in abstract ways, we get off the point, we get into arguments that are not essential to what the argument is really about. We’re always messy. That, really, was the point of Diner.

The Baltimore Sun, in its review back then was critical, like ‘How can you like guys like these? They’re so terrible,” which was sort of to miss the point. We do things that are somewhat cruel, not necessarily with bad intentions, but we’re imperfect. Show us as we are. Our immaturity, our stupidity is part of us.

I saw Grease and thought it was great fun. When I wrote Diner, I was thinking, “How can I make it closer to what I really remembered it being?” It’s not bright and cheerful. I wanted to do a stripped-down version that was closer to what I remember.

Reiser: I remember seeing it the first time and my jaw hung open. A, that it held together, and B, that it had such a strong sensibility, the look, the darkness—which was very courageous, it had a very dark look. Other than the horse scene, I don’t think there was a daylight shot in it. That’s odd. How many movies are just nighttime?

Bacon: When I first saw it, I was worried because it wasn’t a super-commercial movie. It’s darker, and I was afraid people wouldn’t be able to tell us apart. It’s weird to think that I would be worried about commerciality at that point in my career, but I was. I was afraid it didn’t have the pizzazz that Police Academy had (laughs).

“There was a real chance it wouldn’t come out. We didn’t have a release date.” -Mark Johnson

I was at a screening and I’m standing at the urinal, literally with my dick in my hand, and the guy next to me says, “Hey, were you in that movie?” And I say, “Yeah,” and he said, “Yeah, not so much,” and he wiggled his hand. Then he said something like, “Yeah, it was a sleeper—I slept.”

Johnson: There was a real chance it wouldn’t come out. They tested it in a couple places, including Baltimore, and it didn’t test well because they set it up wrong. They cut trailers that were like, “Look at those cars zipping around Baltimore—those crazy kids!” And nobody wanted to see that movie. We didn’t have a release date. It was on the shelf.

It turns out, one of my mother’s best friends was [film critic] Pauline Kael, who was at the height of her power at The New Yorker. I literally snuck it out of the studio and showed it to her and columnist James Wolcott in a little screening room, and she loved it. She called MGM and said, “You guys are about to have egg on your face because I’m about to give this movie a rave review, and it’s not going to be available.” So they reluctantly released it in one theater in Manhattan, and it took off.

The irony is that every movie since then, I would show Pauline, and she didn’t like them. It wasn’t until Bugsy that there was another Levinson movie she liked.

Michael Sragow, film critic, The Baltimore Sun, formerly of Rolling Stone: I wrote for Rolling Stone from the L.A. office. MGM said, “We’d like you to tell us what you think of this movie.”

There were a half-dozen critics at the screening. I thought it was terrific, very fresh and unexpected. The lights came up and you could just tell everyone loved it.

The drama was when were they going to release it? I did an interview with Barry before it opened, and we were waiting for them to release it. Finally, we heard they were releasing it in one New York theater. I called and said, “We’re running this, whether it goes wider or not.” We did and we included a note: “The movie slipped into New York theaters without the benefit of an ad in the Sunday New York Times. Though it’s won several rave reviews, the movie’s fate still hangs in the balance.”

Levinson: They put it into The Festival on 57th Street for a weekend. And Pauline Kael gave it a rave. Rolling Stone was a rave. The New York Times was a rave.

We broke the house record, and we started going from there. We went to Boston and we broke a house record. We kept breaking records, but MGM still wouldn’t put us out because they didn’t think it would work to a popular audience.

We never had more than 200 prints. It played for a year throughout the country, but it never went wide because they didn’t believe it could play to a broader audience. They saw it as this obscure foreign film.

It’s always been the sorta stepchild to the studio. Even now, it’s not on Blu-ray.

Johnson: You talk to filmmakers who we admire today, and they talk about how seminal Diner was for them.

Bacon: It’s interesting to hear the people who found it influential: Nick Hornby, Judd Apatow, [West Wing producer] John Wells. Important ground got covered there.

Levinson: The fact that it’s endured is amazing. The Broadway show is exciting. Sheryl Crow wrote music that is fantastic, very compatible with the pieces. It’s a good reflection of what Diner is. The storyline is the same. I didn’t reinvent it.

Johnson: Barry was neither one of the Diner guys nor one of the Tin Men. He was always looking in the window, watching. You see it in his writing. He’s a great observer. He taught me that it has to be about character. No matter how plot driven a movie is, if there’s no characters, there’s no point. If you like the characters, nothing can happen and you’re still happy.