Arts & Culture

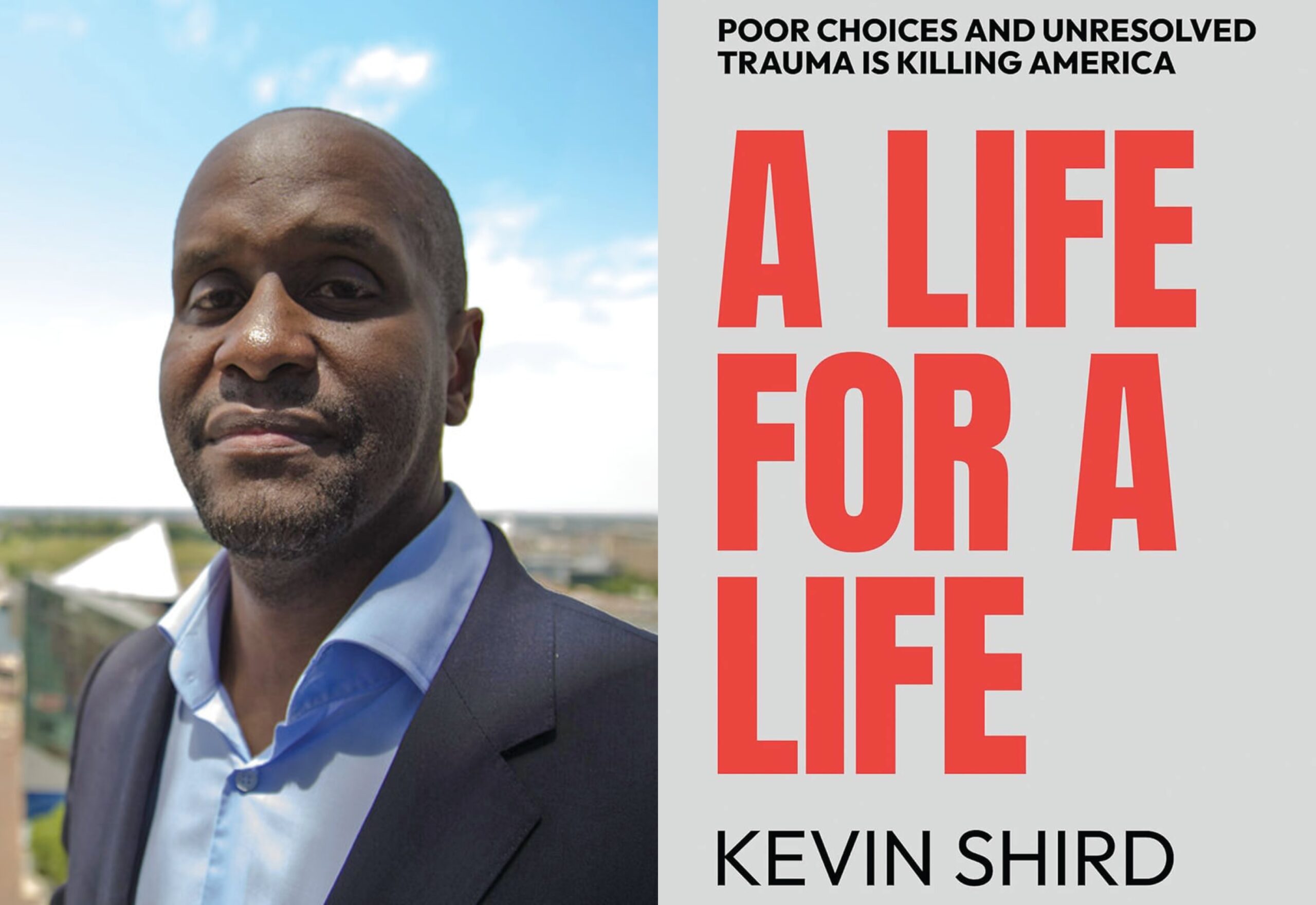

Kevin Shird’s New Book Makes a Compelling Case for Access to Mental Health Resources in Prison

In 'A Life For a Life,' the formerly incarcerated author examines his struggles with PTSD, as well as those of former cellmate.

Kevin Shird’s writing career began in a federal penitentiary. The son of an alcoholic father, the Baltimore native began dealing drugs at 16 and spent nearly 12 years in prison. Determined to improve his circumstances, Shird took college courses while incarcerated and, in the process, discovered that writing was a healing outlet.

He has since written four books including his latest, A Life For a Life: Poor Choices and Unresolved Trauma Is Killing America. In it, Shird examines his struggles with PTSD as well as those of former cellmate Damion “Soul” Neal, a bright, if erratic, fellow Baltimore native. Shird later lost touch with his old cellmate, and then was horrified to discover Neal had been arrested again and charged with killing an ex-girlfriend and her new boyfriend after a drinking binge. Shird wrestles with Neal’s troubling crime, but also Neal’s mental health issues.

A talented writer, Shird weaves several threads together in a compelling case for greater access to mental health counseling in prison and destigmatizing therapy.

Your last book, The Colored Waiting Room, which included conversations with Nelson Malden, the first African American to run for elected office in Montgomery, Alabama, was particularly well-received. What got you started writing while incarcerated?

In the prison college program, it wasn’t so much about writing at first. It was more about reading. The prison library had a collection of biographies of world leaders—Nelson Mandela, Golda Meir, Yasser Arafat—all easy to read. I didn’t have an interest in fiction, but in all the “true stories,” the biographies, and nonfiction.

In fact, your first book was a memoir.

I had an aspiration to write. I think everybody says, “I’m going to write a book one day.” Few people move on it, but I was one of those people.

What prompted this current work and your investigation of your former cellmate, Damion Neal?

I first met him in a holding cell in a federal Virginia facility and then, two months later, again in Allenwood. It wasn’t until 2009 that I googled him. Just the way you get curious about people, and I read about his arrest, which had been a year earlier. I was in shock. I didn’t believe he did this for a couple of years, until I started researching the case and getting paperwork from the court.

And you two had been close for a period.

I’d get him to come up to the library. We’d check out books and talk for hours. He’d talk about going home to his daughter and stuff like that. You bond with guys inside, develop a camaraderie. It’s almost like a guy you went to war with, and you want him to be successful and then when he’s not, you feel some kind of way about it. I have that still with guys who I was in the joint with. When I see them doing great, it lifts me up.

This took 10 years for you to write. Were you busy with other projects? Or was something else going on?

That’s how long it took me to wrap my arms around the issue of mental health. I also had a psychologist tell me it was survivor’s guilt. You know, I made it through the storm. I think we all, at some point in our lives, jokingly say things like, “that’s my crazy buddy” or “that’s my crazy home boy,” not realizing that we’re referring to someone maybe dealing with a serious issue unbeknownst to us. When I spent time around him, I knew something wasn’t right. I just had no idea what it was. It took me 10 years to really understand what unresolved trauma is. Growing up, his parents were both drug addicts. He had held a dying friend in his arms who had been shot in the head. He’d witnessed a mass shooting, and he suffered from lasting PTSD.

You highlight the lack of access to mental health care for those incarcerated and the connection to recidivism, but also the need in low-income communities.

We have to make sure that people understand they need support and make sure people have access to support. Eventually, I realized I needed help—counseling and therapy—but there has never been a hesitation. If your teeth hurt, immediately you think, “I need to go see a dentist.” We’ve known anxiety and depression are not great for human beings. But in these communities, there is a lack of access to this type of care. We’ve got to make mental health just as simple and accessible for people who are struggling.