Arts & Culture

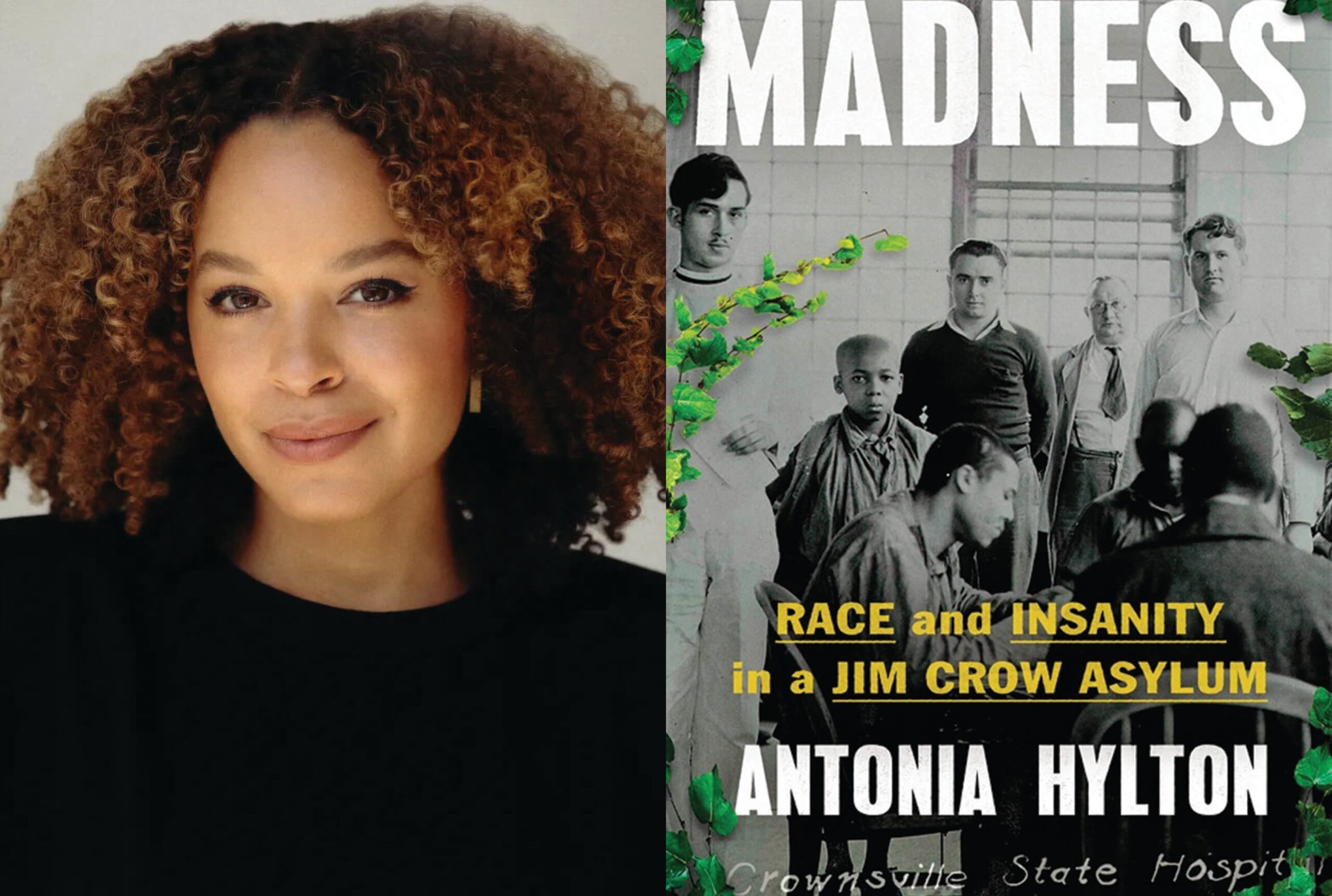

Antonia Hylton’s ‘Madness’ Examines Crownsville Hospital, One of the Nation’s Last Segregated Asylums

At its heart, the book by the NBC and MSNBC correspondent is a look at who America deems sick or criminal, and who is deemed worthy of care.

NBC and MSNBC correspondent Antonia Hylton has deep Maryland roots. Her maternal grandmother emigrated from Cuba to Baltimore as a teenager and her mother was born here. But her family’s local connections are also complicated. Her grandmother, who was Black, and her grandfather, a white Johns Hopkins doctoral candidate, couldn’t legally wed in Maryland and married in Washington.

A history and science major at Harvard with a concentration in psychiatry, Hylton initially stumbled across the story of the segregated Crownsville Hospital Center while searching for a senior thesis project. Founded as the Hospital for the Negro Insane of Maryland, Crownsville’s problematic 93-year history ultimately became the subject of her recently published first book, Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum.

More than merely chronicling the past, Hylton weaves recollections from surviving employees and patients with hospital records—and speaks candidly about her own family’s history with mental health. Hylton notes how jail and prison populations exploded in the wake of mental-health institution closures. At its heart, Madness is an examination of who America deems sick or criminal, and who is deemed worthy of care.

This is such a complex and nuanced story. I’m in awe of your research, which includes not only hospital records, but also photo- graphs dating to the hospital’s earliest years.

Paul Lurz is the first former employee I found, and he wasn’t hard to find because he is passionate about the hospital’s history. In the chaotic months as the hospital neared its end and the state was telling employees they needed to pack up and leave, he made a personal, split-second decision to start gathering up records and photographs that he found strewn all over place. Paul preserved everything he could find in a fireproof cabinet in his office.

Conditions at Crownsville, where patients received half the per capita funding that white institutions received, were often bleak—particularly in its first decades. But you also find former staff, who, despite limited resources, genuinely did the best they could for patients.

This is not a one-note story. It’s not about a “spooky asylum,” even if parts of the story can bring you to that place. It’s also about a Black community rising up to become their own heroes. It’s about a generation of health care workers who did a lot of work and reform without much credit. It’s about people who to this day are driving around Maryland, visiting former patients that are living on the streets or living in group homes, and they believe still deserve more.

Then, there is the story of a Holocaust survivor named Jacob Morgenstern, whose post-World War II leadership tenure becomes a major turning point.

Crownsville is one of the few places willing to hire Jewish people and to give them leadership roles with access to patients and the ability to make an impact. He moves his family to Maryland and is shocked because, as an outsider who has just left an apartheid system himself, he can see Crownsville for exactly what it is. In fact, one episode that’s a bit comical is the administration’s concern that this immigrant Jewish family decorate their home on the property in the Southern style. And they go along with it. But the next minute he’s calling up the NAACP to help start integrating the staff.

You share the police shooting death of your father’s cousin Maynard, who was armed and in the throes of a mental health crisis.

Maynard’s younger brother says he doesn’t want the pain to ever go away because it would mean he’d forgotten how important Maynard was to him. It’s heartbreaking, but at least he can talk about the loss. Working on this book, I learned if you try to hide your story, swallow your pain, and depress difficult memories, that you make yourself sick and can even change your DNA, passing on your pain, your anxiety, your grief to generations that come after you. The only way forward is to turn back and face your family history, to face the hurt.

Finally, there is the unlikely friendship of local Black historian Janice Hayes-Williams and Anne Arundel County Executive Steuart Pittman. They hope to turn the Crownsville grounds into a memorial, museum, and healing park.

One is the descendant of slaves, and one is the descendant of slave owners. On the surface, they look like examples of the current American divide. But instead of fighting and harping on each other’s differences, they are working closely together to try to figure out what healing could look like in Anne Arundel County.