Arts & Culture

Rafael Alvarez’s ‘Don’t Count Me Out’ Tells Story of Recovering Addict Bruce White

White’s willingness to share his struggles—combined with Alvarez’s reporting and writing—make this a book you’ll read in one or two sittings.

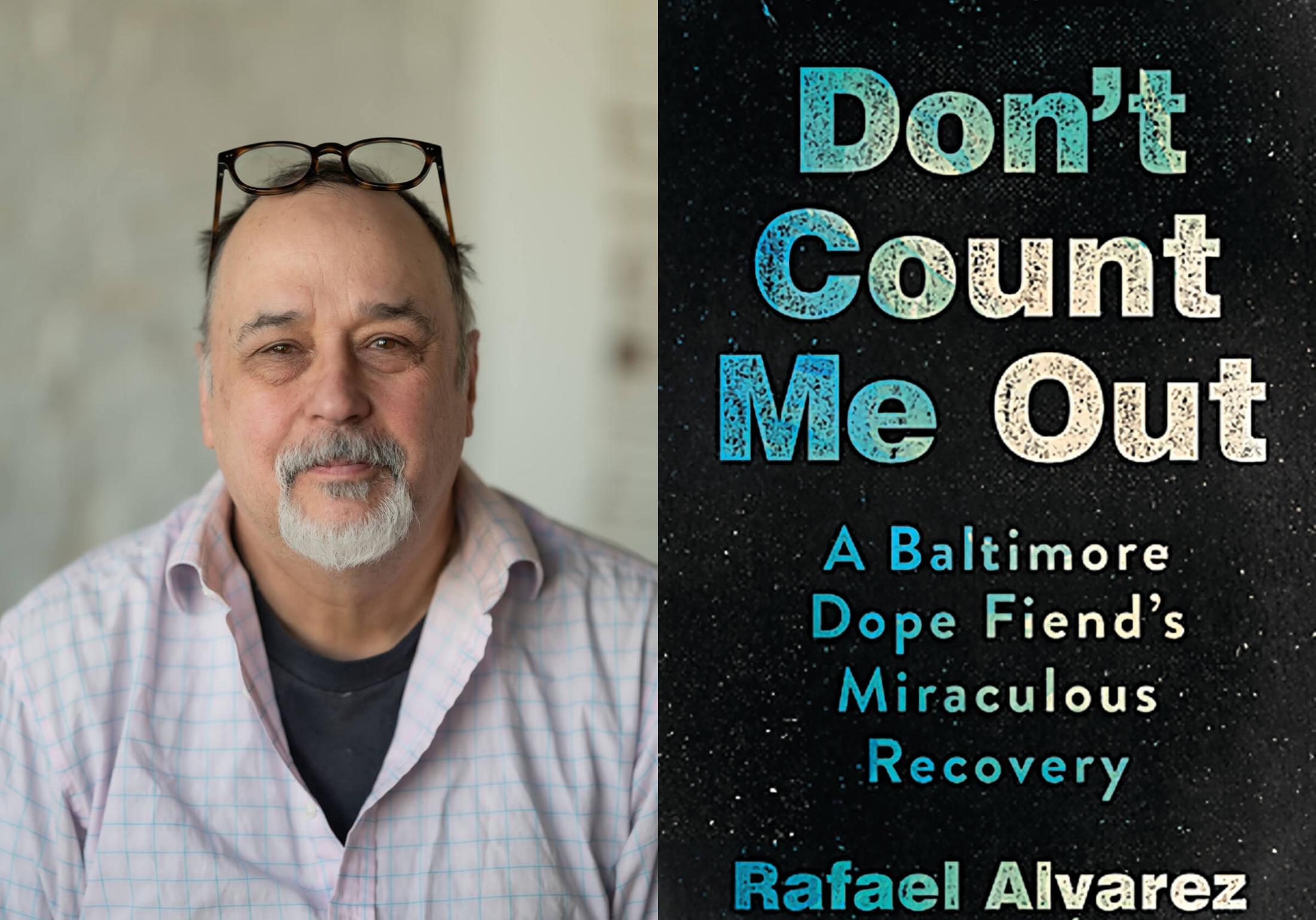

Rafael Alvarez is a former Sun reporter, The Wire staff writer, and author of nearly a dozen books that he notes with a smile are “all about Baltimore.”

A prolific freelance journalist and occasional contributor to Baltimore, Alvarez is also one of the best profile writers in the city—and as far as complicated subjects go, he has met his match in Bruce White. The recovering drug addict at the center of Don’t Count Me Out: A Baltimore Dope Fiend’s Miraculous Recovery, White has an ugly and at times brutal past that includes violence and incarceration, which Alvarez handles with a reporter’s objectivity and eye for detail, and a novelist’s understanding of character and narrative.

Don’t Count Me Out is the story of a man almost everyone would have considered a hopeless addict and criminal, yet someone who eventually found grace. Or, as White would describe it, grace found him. Today, he runs a treatment center and several recovery houses, helping hundreds over the years to recover from addiction.

Recovery stories are inevitably both personal and universal, and it’s White’s willingness to share his early sexual assault, the deeper truths behind his middle-class upbringing, and his own insecurities—combined with Alvarez’s reporting and writing—that make this a book you’ll read in one or two sittings.

Reading Don’t Count Me Out, the book that popped to mind was The Night of the Gun by former New York Times reporter David Carr, in which Carr goes back and, with a reporter’s commitment to the facts, interrogates his own addiction and dark past. The difference obviously is you are reporting Bruce White’s story, but the rigor is similar. Did you ever read that?

No, I haven’t, but I know of the book and I’m somewhat familiar with David Carr’s story. Writing this book was a lot of old-fashioned, shoe-leather reporting, going through archives and court documents, and finding his reclusive and estranged older brother and bringing the two of them together.

You also tracked down old friends, classmates, and even his junior high school assistant principal, among others.

When a Baltimore County career educator now in his 80s, who must’ve had 250,000 students over the years, remembers you, it’s because you stood out. For better or worse. Bruce kept pushing me, “When’s the book going to be done?” But that’s why it took 10 years to finish.

How did you guys meet?

He was looking for someone to tell his story and a mutual Baltimore acquaintance told him I was a writer and suggested he should reach out to me. And they gave him my cell number. I was in Los Angeles, trying to hustle up work after the Writers Guild strike and Great Recession, when he called. So, you know, I said yes. The only promise that I made was that I would produce a professional manuscript.

The first chapter is remarkable—and unexpected, to say the least. White flatlines on the way to the hospital after being shot by a SWAT team. What he experiences after “dying” is not the cliché white-light rapture, however, but a descent into something akin to Dante’s Inferno.

The detail and vividness of it were kind of startling. It’s the only thing in the book that I couldn’t fact-check. Not without some sort of divine intervention. It’s his memory of what he experienced—and he wanted to die when he came to—that was the physical pain and mental state he was in. As a writer, I knew when he shared it, that’s where I wanted to start the book. It’s terrifying and it sets everything else up.

How would White, now in his 60s, explain his transformation? The man in his 1998 mugshot and the man in the current photos in the book are two different people.

Oh yeah, he looks like a maniac in that photo after he’s been arrested. He’d attribute it to prayer and meditation. That simple. He prays five times a day.

What do you hope readers take away?

He came from a middleclass, Leave It to Beaver home in Lutherville. His parents had their own issues, but they loved him. He did Cub Scouts, played baseball—had dance lessons in the first grade—went to Ocean City in the summer. Addiction doesn’t care. He still ended up in prison. That said, I wouldn’t have done this book if there wasn’t a redemption. Years later, when he was clean and running a treatment program, a woman told him that a male house manager had demanded sex in lieu of rent. It led to him establishing his first residential recovery house, which accepted only women.