Arts & Culture

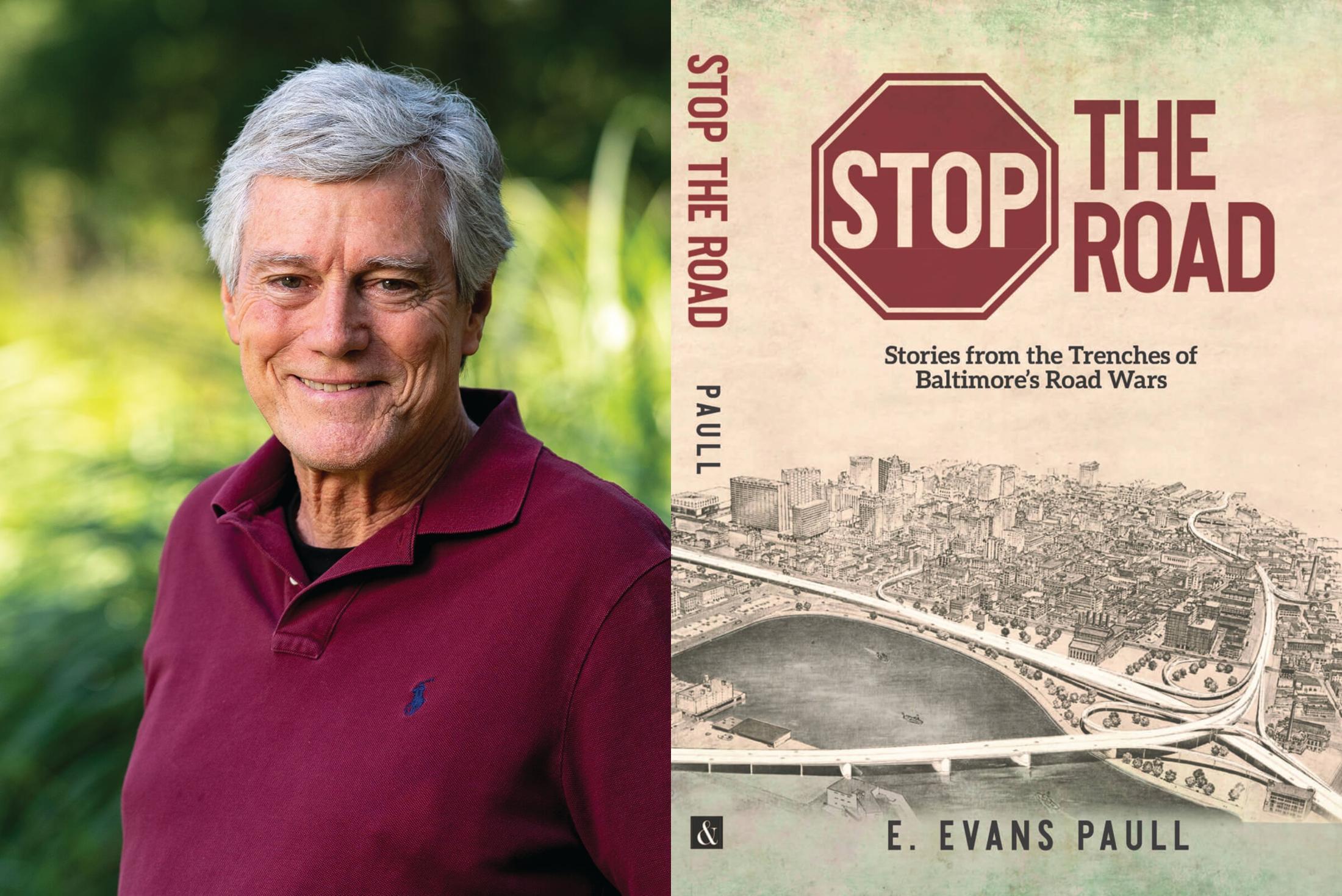

Longtime Urban Planner E. Evans Paull Explores Historic Baltimore Road Wars in New Book

'Stop the Road: Stories from the Trenches of Baltimore’s Road Wars' is a must-read for anyone who wants to better understand how the Baltimore of the 1940s and 1950s became the city we know today.

Whether you enjoy living in Fells Point, Canton, Harbor East, or Federal Hill—or simply appreciate a stroll along the vast Inner Harbor promenade—you have a tenacious group of grassroots activists to thank.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, they managed to stop Baltimore business leaders and politicians who were stubbornly intent on building an east-west expressway, including a 14-lane interchange over the water where Harbor East now sits that would connect I-70 to I-95 and I-83. On the other hand, if you are from Rosemont, Harlem Park, or Poppleton, you know that similar efforts to save your neighborhood from its destructive path were not successful. The little-used, 1.39-mile expressive stub that did get built in West Baltimore became known as the Highway to Nowhere.

Mount Washington resident E. Evans Paull began his career in the City Department of Planning and spent 45 years overall as an urban planner. For the past five years he’s been researching his first book, Stop the Road: Stories from the Trenches of Baltimore’s Road Wars, a compelling must-read for anyone who wants to better understand how the Baltimore of the 1940s and 1950s became the Baltimore we know today.

Many people know Sen. Barbara Mikulski got her start as an activist trying to stop the planned expressway from tearing up Fells Point and Canton, where she grew up. But you tell a much fuller story, highlighting several activists in Southeast Baltimore.

Other folks that I highlight are Tom Ward, Bob Eney, Lu Fisher, and Jack Gleason. They were all in on the formation of [what is today] The Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fells Point. Another name that pops up is Roland Reed, he was the guy that came up with the Fells Point Fun Festival. Those were the four or five leaders of the Preservation Society that stuck to their guns, won over public opinion, and mounted legal and regulatory challenges that forced the adoption of an alternate route that the City could not finance.

The Fells Point Fun Festival was launched to raise support, and funds, for the cause of stopping the construction of the expressway.

That’s right. I do highlight a disagreement in the preservation society about this. Most members thought it was a bit crazy to do this festival, when they were just getting their legal challenges [to the expressway] off the ground. But they all later admitted it was a brilliant idea.

Interestingly, as you note, The Federal Aid to Highways Act of 1966 had a provision to protect parks and natural habitats, which Baltimore activists realized could be a vehicle for tying up the expressway plans in court.

Bob Eney was the guy who really articulated the historic and architectural details in Fells Point. One of the key things early on, was that local preservationists brought in the staff from the new president’s advisory commission. Bob served as tour guide, and he must have been convincing because the advisory council strenuously objected to the highway plan.

Unfortunately, Mayor William Donald Schaefer kept pushing ahead in West Baltimore even as expressway plans elsewhere were dead or dying.

He was obsessed with this. He was going to be the guy that broke the log jam and got the highways done. He had kind of internalized the case that had been made by the engineers. He was also a very strong pro-business guy, and the Greater Baltimore Committee was the No. 1 cheerleader behind the highway plan.

The book is a towering work of research. What initiated your interest in this story?

I was drawn to the sort of shocking victory of the outsiders and relatively powerless folks over the insiders and the powerful. It’s not often the Greater Baltimore Committee, the mayor, the governor, 17 of 18 city councilmen, and the engineers—who are all behind these highway plans—wind up getting beat by activists who had no one in their camp with any kind of résumé, except Tom Ward, who was on the council in the mid-1960s.

The irony is that if the city business interests advocating for highways had been successful, it would’ve been economically disastrous for the city. The later redevelopment of all those [Harbor] neighborhoods might not have happened if the highways had been built. Finally, there is the fact that the highway planning of the era is very revealing in terms of racial equity and environmental justice issues, and I wanted to bring that part of the Baltimore highway story to light.