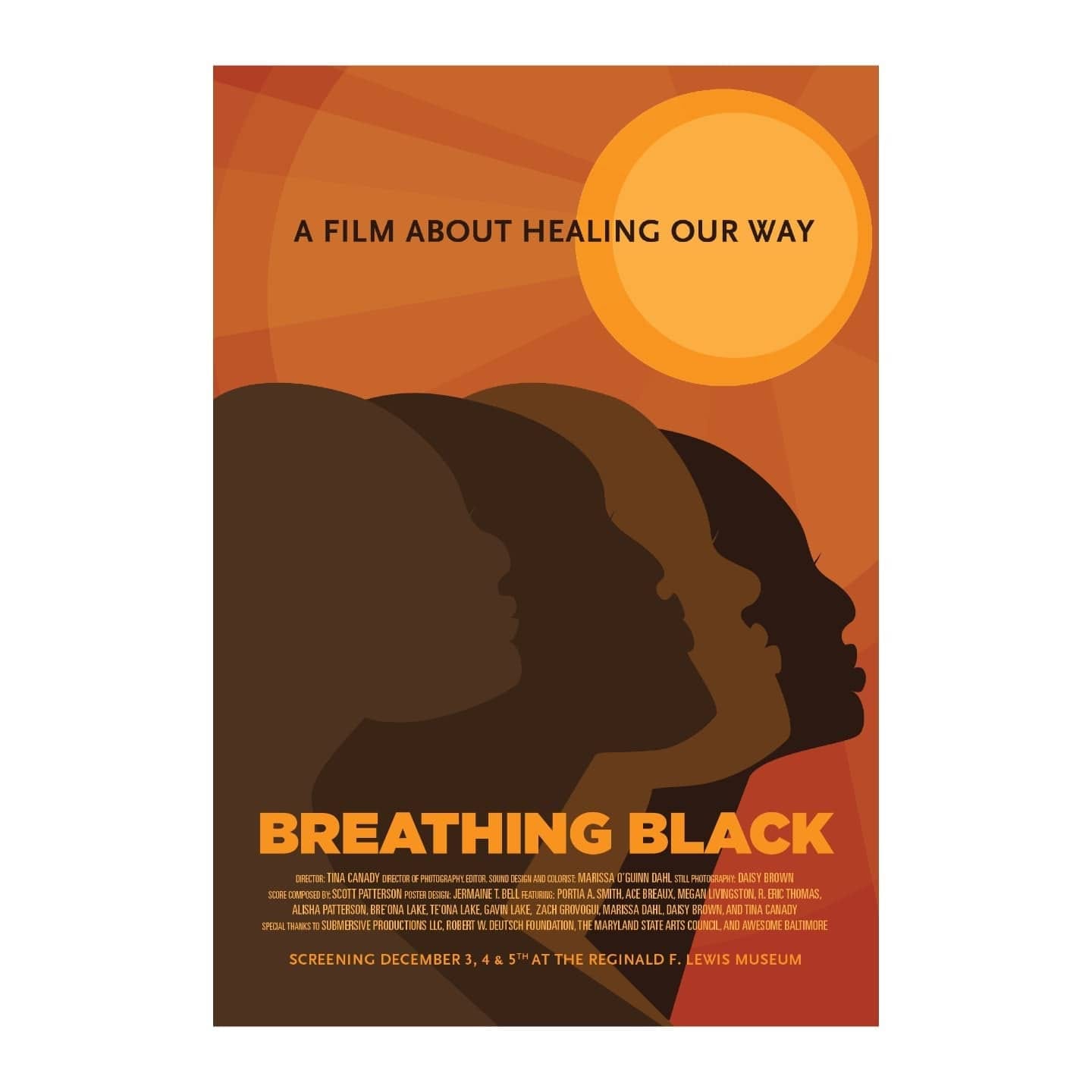

[Editor’s Note: Special screenings of Breathing Black with after-show talkbacks are scheduled at The Peale Center on July 9, 2022 at 5 p.m. and 8 p.m., as well as on July 10, 2022 at 3 p.m. Tickets can be purchased, here.]

In her directorial debut, Breathing Black, Baltimore filmmaker Tina Canady initiates a timely and necessary conversation: How do Black Baltimore residents heal and make space for joy during their genocide? It’s a question that arose for Canady—a seasoned thespian who holds a BFA in drama from NYU and has graced the stages of many local theaters—during the height of the pandemic, in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. To dig deeper, she assembled an all-Black creative team to interview Black Baltimoreans about their connection to joy, healing, and breath.

Ahead of the premiere at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum on Friday, December 3, we sat down with Canady to talk about the idea behind the documentary, her views on mental health, and where the film is set to take its next breaths.

Can you talk about the impetus behind Breathing Black?

The idea for this film was conceived right after the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Personally, I was feeling so depleted and isolated, as we were in the midst of a pandemic. I sat down with my therapist and we had a lot of conversations, but in one of them she asked me, “How do you restore or replenish yourself with everything that’s going on? How do you heal?” And I didn’t have that answer. So this journey was me seeking my own healing and seeking that answer for myself. The making of this documentary was about the journey I’ve been taking to find healing in all of its many forms, for myself and for Black folks all around me.

You come from a theater background, so your typical storytelling platform isn’t film. What made you want to create a documentary?

I found myself in a place of having a story to tell, but I didn’t have the ways that I’m usually able to tell it with theaters being shut down at the time. I was challenged with the internal question of, “How do I find a new way to tell this story?” And it was through film and talking to people that it really came about. I was terrified because I’ve never made a film before. So I took that leap of faith and grew my passion for filmmaking alongside an exclusively Black creative team, [some of whom are actually featured in the work.] I was so intentional [about that.] It’s definitely something I hope to do again in the future.

Healing is such a clear theme in the film. How do you define healing?

Healing is such a non-linear process. Using the lens of this film, I kind of viewed it as a specific strategy for our liberation as Black folks and our ongoing journey toward wholeness. I looked at it as joy—joy being the thing that could help us navigate all the things that we do go through as an oftentimes oppressed people. It was about seeing the strength in joy and how our joy is so very connected to our healing—intertwined for our greater good.

I really love how you’re able to personify joy as something with its own character traits, and how you framed your questions around that. Some of the questions for your interviewees are: “What is Black Joy’s favorite song?” “How do you nourish joy?” “Where do you see Black Joy at its peak?” Why did you want to emphasize the concept of Black Joy in this film?

Joy has played such an important part in my life and how I’ve navigated through the world. I feel like there’s more space for that. And even after a film like Breathing Black, I want more space and narratives about Black Joy. I have been emphasizing that as a mission for myself this year and I really hope that comes through the screen—joy and its presence, its power, and how other people might reflect on it collectively, even though when we think about those moments of joy it might come from a very personal, intimate space.

Black Joy means freedom. Doing it our way on our own terms. For me it means power. There’s so much power in joy as a means to navigate or a strategy to navigate oppression. My hope is that with the experience of watching the film, I’ve curated a place where we as Black folks can celebrate joy and rest. I hope that this project honors our ancestors who navigated the brutality of enslavement and also passed down immense Black Joy to us. Black Joy is our inheritance, and it’s my hope that viewers will cash in on the inheritance to inherit that joy themselves.

You mentioned that the initial idea was sparked by a question posed by your therapist. What is your relationship to therapy and what are your thoughts on Black folks seeking therapy?

My mother is a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst, so I grew up with casual conversations about therapy in my formative years and learned the importance the role therapy would play in my life very early. I’m very grateful to have my mother. She’s always taken such pride in being in a profession that she loves and puts so much value into. I feel like some of that transferred over to me. I see so much value in therapy. My partner is also a clinical psychologist, so I am really, truly surrounded by the power of therapy and the power of communication. It is never a bad time to be in therapy. No matter what we might be going through, we could all really use that space to really invest in ourselves and invest in how we navigate our relationships, the world, and its current events. I’m glad to be able to bring those themes of talking to get through in Breathing Black.

What are your hopes for Breathing Black? Where do you want the film to live and breathe (pun intended)?

I think Breathing Black should be shown all over the world. I really love the narrative, and Baltimore is such a beautiful place to tell this story from. I don’t just say that as a writer, but as someone who genuinely just likes to talk to people. The dream for this film is for it to reach as many Black people as it can. I made this for Black people to honor them and to honor Black Joy. So to anyone that comes into contact with it, I am immensely grateful. Maybe it’s at film festivals or in an archive, or some kind of streaming service—wherever it’s at, I’m just grateful it’s out, and breathing.