Now celebrating 25 years in Baltimore, AVAM is a reflection of the woman who created it.

Arts & Culture

Now celebrating 25 years in Baltimore, AVAM is a reflection of the woman who created it.

Even before you enter the American Visionary Art Museum, the grounds set you up for what you’ll experience inside. Mosaic sculptures stand near the entrance on Key Highway in Federal Hill—there’s a shining, giant-sized egg and a bedazzled tree sculpture called The Universal Tree of Life that throws sparkling light onto the sidewalk. A small Meditation Chapel, made of found wood, allows space for private retreat and is open to everyone. The word LOVE spans across the brick Tall Sculpture Barn in glowing, neon letters. More words—“O SAY CAN YOU SEE,” a nod to Francis Scott Key—shine on the Jim Rouse Visionary Center next door, with its huge metal “nest”. But perhaps the greatest spectacle is AVAM’s main exhibits building, whose curved exterior wall is covered with a glass and mirrored mosaic that reflects the light of Baltimore amid its spiraling design.

Even before you enter the American Visionary Art Museum, the grounds set you up for what you’ll experience inside. Mosaic sculptures stand near the entrance on Key Highway in Federal Hill—there’s a shining, giant-sized egg and a bedazzled tree sculpture called The Universal Tree of Life that throws sparkling light onto the sidewalk. A small Meditation Chapel, made of found wood, allows space for private retreat and is open to everyone. The word LOVE spans across the brick Tall Sculpture Barn in glowing, neon letters. More words—“O SAY CAN YOU SEE,” a nod to Francis Scott Key—shine on the Jim Rouse Visionary Center next door, with its huge metal “nest”. But perhaps the greatest spectacle is AVAM’s main exhibits building, whose curved exterior wall is covered with a glass and mirrored mosaic that reflects the light of Baltimore amid its spiraling design.

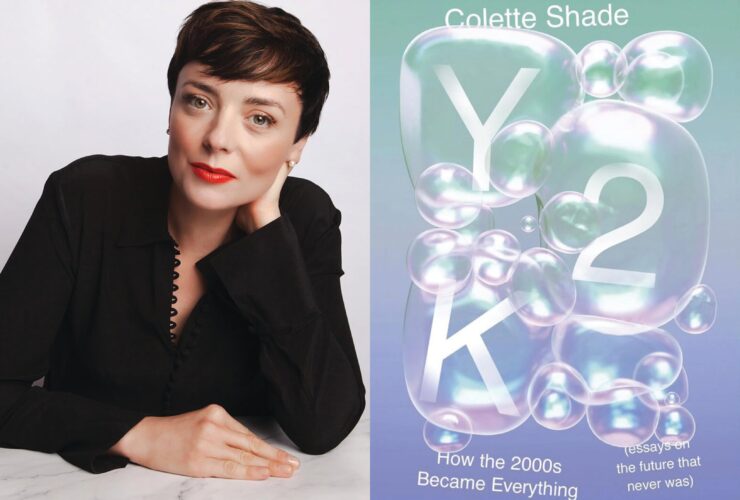

Rebecca Hoffberger

While most museums look like fortresses, with large and imposing entrances that you enter head on, at AVAM, you slide into the building from the side. Once inside, a kind of gravitational force is at work. Its first, long hallway slopes upward. As you walk, you spiral inward toward the building’s center, ascending and rotating. Perhaps your conscious mind doesn’t pick up on this movement, which continues throughout the museum, but your subconscious mind certainly must. Like the exterior, the interior hallways and stairwell are curved, rather than the usual symmetrical angles, and their organic shapes are reminiscent of being inside some kind of large, cosmic womb. Gallery walls are rounded, too, and painted a collection of vibrant colors. And throughout its three floors are pieces of art made with unusual mediums. You might see a sculpture made from thousands of toothpicks or a picture painted with mustard and ketchup, because those were the only materials the artist had available. Wall texts merge the artwork with science, philosophy, and spirituality from around the world.

The brainchild (or perhaps lovechild) of founding director Rebecca Hoffberger, AVAM was the first major museum of its kind when it was created, showcasing the work of self-taught artists and visionary thinkers. Like the art inside and the woman behind it all, AVAM and its events are fueled by intuition. You’re meant to move about the museum intuitively. There is no right or wrong way to go from gallery to gallery. The structure itself gives you the freedom to explore however you’d like.

“It is very important to view the physical building as a manifestation of Rebecca Hoffberger’s spirit,” says architect Alex Castro, who brought the museum to life in 1995, along with architect Rebecca Swanston. “It is unique because she is unique, not because of any special architectural manipulations. The structure is her spirit made concrete.”

“Creative acts of social justice constitute life’s highest performance art. To be someone who creates social change, you have to be fiercely creative.”

This year, AVAM celebrates 25 years here. From humble beginnings (Hoffberger says she did not take a salary for the first 15 years), it has become a nationally recognized museum, one that draws visitors and celebrated thinkers from all over the country and world to Baltimore. Perhaps this is because the museum has always catered to all ages and all walks of life—not simply the art elite. Whether through its annual mega exhibitions that have explored topics as far-ranging as food, religion, and parenthood; through its museum shop, Sideshow, with its wall-to-wall art, books, games, toys, even a fortune-telling machine; or through its quirky and freewheeling public events, AVAM has a little something for everyone who’s curious about the mysteries of life and their place among them.

It also provided a home for so-called “outsider” artists whose work might never be seen otherwise.

“A door opened for me into a world of common purpose and intention . . . an invitation to create outside the historical limitations of a conventional art community that I knew would never see or accept me,” says Frederick artist Geraldine O. Lloyd, whose painting “Hope” was exhibited at AVAM in the show All Faiths Beautiful. “AVAM mirrored my heart of hearts, that art was a spirited and passionate beast of imagination that had to run wild in pastures of its own making. And I was now one with many, on fire with inspiration and intention.”

The museum's inviting entrance.

Many people who know Hoffberger will describe her as one in a million, someone they feel blessed to have met, someone who radiates an infectious, almost magical enthusiasm for life and all its eccentricities and synchronicities. With her long, wavy, strawberry-blond hair and depth of spirit and intellect, she’s a colorful figure and widely admired in Baltimore for her originality and devotion to her mission, which has made an unparalleled contribution to the art world in Baltimore and beyond.

Many people who know Hoffberger will describe her as one in a million, someone they feel blessed to have met, someone who radiates an infectious, almost magical enthusiasm for life and all its eccentricities and synchronicities. With her long, wavy, strawberry-blond hair and depth of spirit and intellect, she’s a colorful figure and widely admired in Baltimore for her originality and devotion to her mission, which has made an unparalleled contribution to the art world in Baltimore and beyond.

LeRoy and Rebecca

Hoffberger, who turned 67 in the fall, is the first to say she does not come from a traditional museum background. It seems she was always an out-of-the-box thinker. At 8, when asked what she wanted to be, she replied, “An alchemist.” (She thinks she’s achieved that through AVAM.) She grew up in Baltimore in a family that she believes had extrasensory gifts. The gift was so natural, they took it for granted, she says. She spent so much time outdoors, she says wild birds would land on her shoulders and she was able to hug deer. At 13, she was going to lectures at the Theosophical Society and getting psychic readings at the Palmer House restaurant near Lexington Market. She gobbled up lots of spiritual teachings and was the kind of girl who would ask a date, “So, what do you think about death?”—not ever much interested in chitchat. At 15, she was elected head of Baltimore Washington High School Coalition, where she led the successful fight to change the dress code to allow girls to wear pants.

By 16, despite being accepted to multiple colleges, Hoffberger left for Paris to study mime arts under Marcel Marceau. She was his first American apprentice. She went on to found a ballet company, study folk medicine, and deliver babies in Mexico, and she eventually made her way back to Baltimore, where she worked with the People Encouraging People (PEP) organization at the Sinai Hospital Department of Psychiatry. While helping patients with rehabilitation and reentry into society, the idea for a “visionary” museum was ignited, as she heard more and more about patients—at Sinai and elsewhere—who had made incredible works of art.

Hoffberger at the Pet Parade.

For instance, she met a man whose late father had painted while hospitalized for mental illness. Because his mother had such traumatizing memories of his father’s illness and suicide, she couldn’t stand to look at his work, but the son wondered if he could share it with Hoffberger. “It was beautiful,” she says. Soon after, she exhibited his paintings in a miniature art show throughout PEP.

Hoffberger was also greatly inspired at the time by what avant-garde French artist Jean Dubuffet was up to. He’d been a successful artist but was fed up with the art world and began working instead in his family’s business, importing and exporting wine and Champagne. “Because he was well known, people started sending him their art,” Hoffberger says. “They were psychic mediums and truck drivers and prisoners, and their work began to get him interested in art again.” Dubuffet started exhibiting the work of these outsider artists and became the founder of the Art Brut movement. Hoffberger visited Switzerland in 1985 with a group that included her future husband, philanthropist LeRoy Hoffberger (who also became a co-founder of AVAM), to see Dubuffet’s collection and make a short film about it. After seeing firsthand what he had done, she returned to Baltimore and decided to found her own museum of what she coined “visionary artists.” She felt the more traditional terms—“outsider” and “naïve” artists—carried a negative connotation, she says.

She located what would become AVAM’s main museum at 800 Key Highway, a building that had formerly been the offices of the Baltimore Copper Paint Company, and immediately began fundraising. Next, she had to hire architects. “Everybody was saying, ‘Oh, you have to have Frank Gehry design your building,’” she remembers. “I chose only local talent.”

The primary architects to design AVAM were Swanston, who lived in Hoffberger’s neighborhood, and Castro, a design architect who understood Hoffberger’s vision. Her vision paid off. In 1998, AVAM was the first museum in the United States to win the National Award for Excellence from the Urban Land Institute, which honors architecture and design.

an AVAM art car.

After a decade of planning, fundraising, and constructing the space, AVAM was ready to open its doors to the public. Its grand opening was held on Thanksgiving weekend in November 1995. Gerald Hawkes, a Baltimore artist who struggled with chronic mental illness and made large sculptures composed of hand-dyed matchsticks, was the first person to walk inside. His matchstick art was displayed in the inaugural exhibit, Tree of Life. Three years later, after a bout with pneumonia, his ashes would be spread during a ceremony at the Meditation Chapel’s wildflower garden.

In the ensuing years, the museum and Hoffberger garnered praise and awards from institutions and media outlets across the country. In 2017, the American Folk Art Museum awarded Hoffberger its annual Visionary Award. During the ceremony, Colin Eisler, an art historian and professor of fine arts at New York University, said of Hoffberger: “Rebecca has liberated creative arts from the big buck’s shackles, bringing its key constituent—inspiration—into focus.”

Ted Frankel, owner and manager of Sideshow for the past 16 years, calls Hoffberger “a force.” He was living in Chicago when he visited AVAM, met Hoffberger, and later got a call from her, asking if he would run the museum store. “She called and said, ‘You’re the one,’” he remembers. “I didn’t want to move to Baltimore, but Rebecca and I are both the kind of people who follow our gut. She’s always just allowed me to be me.”

Scenes inside, including gift shop Sideshow. In the sculpture barn, an art car next to its kinetic sculpture inspiration, Fifi the Poodle.

AVAM is classified as an art museum, but the intuitive artistry exhibited there is only one component of the museum and its mission. As outlined in Hoffberger’s “recipe for curation,” which she has continued to follow for 25 years, every exhibit brings together science, social justice, humor, history, philosophy, and spirituality, mined from the world.

Her formula also includes notes like “Never bore—enchant!” and “Call up anyone you/your staff have long admired and invite them to come take part.”

the mighty Divine statue.

“Even in the beginning, I never would have given so much of my heart and my mind to something that was just about hip, cool art,” Hoffberger says. “I want to share with people what gets you through life and inspires you, rather than, ‘This is by so-and-so and sold at Christie’s for whatever.’ I think it’s too late in the world to just be about visual stuff. A lot of people do that really well, but it was never my interest.

“Visionary thought has always been my interest,” she continues. “The cornerstone is that ideal that creative acts of social justice constitute life’s highest performance art. To be someone who creates social change, you have to be fiercely creative. That’s why my buddies have always been people like Patch Adams and Archbishop Tutu and Dean Kamen. . . . We treat someone’s life’s work as being just as much a work of art as pigment on a canvas. We really do speak to the essence of what it means to be human.”

In the 40 exhibits she’s curated (or co-curated) at AVAM, she has shown work by well-known artists, such as New Yorker Alex Grey and Paradise Garden creator Rev. Howard Finster, alongside lesser known artists, like Frederick-based Dan Patrell, who memorialized his wife by cementing her ashes into a stained-glass piece after she died from cancer. Sometimes art just gets dropped off at the museum door or is found after the artist has died. Some of the museum’s artists are so unknown, major newspapers have contacted Hoffberger to request information about them when writing their obituaries.

Some artists are based in and around Baltimore. Bolton Hill’s Chris Wilson, for example, was a recent addition to the AVAM family in the show Parenting: An Art Without a Manual—but they’ve also come from as far as Australia.

While the outsider artists can come from anywhere, Hoffberger thinks Baltimore is a perfect home for a place that celebrates visionary art. Hoffberger sees Baltimore as a cauldron of sorts, sometimes at odds with itself: neither North nor South; a religious center and yet also the city where Madalyn Murray O’Hair took prayer out of schools. “It’s a town where people who have everything against them—whether it’s Babe Ruth, who [went to reform school], or Billie Holiday, who was assaulted as a child—have always been these great souls that persisted.”

she was was marcel marceau's first American apprentice. she went on to found a ballet company, study folk medicine, and deliver babies in mexico.

Perhaps the only challenge to Hoffberger’s singular vision is finding the right person to replace her. At 67, she admits that she’s slowing down a bit. And while she has no immediate plans to retire, she knows she can’t run the museum forever. Though she’s invited guest artists to co-curate shows with her, Hoffberger has remained the primary curator for 25 years, and she’s written the vast majority of the catalogs and wall text that coincides with each show. She’s also often steeped in research, hunting down artists, and writing grants.

“Rebecca is one of few people you may encounter in your lifetime that can successfully navigate several planes of existence at once,” says Pete Hilsee, former director of communications and marketing at AVAM. “She is simultaneously visionary, deeply engaged in the critical details of museum operations, knowledgeable in an incredibly wide range of fields, and intimately involved in the lives of countless people—present and past staff, friends, family, artists, activists, thinkers, and doers.”

Hoffberger says that if anything were to ever happen to her, her “recipe for curation” will help. She doesn’t plan to hire a headhunting company when she retires. “To find my successor, we’re going to ask people to write us a little about why they think they should take over. Everybody sends out generic resumes. We want them to really work and think about what they would do here.”

Scenes outside, including the famous giant egg and nest.

It was inevitable that a museum that resonates so profoundly with people would imprint its DNA on the town in which it resides. Since opening, AVAM has expanded to host what have become beloved Baltimore traditions, like the annual Kinetic Sculpture Race, which encourages teams to create human-powered floats and pedal and paddle them through town. They also host an outdoor movie series, Flicks from the Hill, a Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration with performances and birthday cake, an annual pet parade, multiple classes and workshops each year, and lectures and conferences that bring thought leaders from around the world, among them Matt Groening, Julia Butterfly Hill, and Arianna Huffington. (Hoffberger jokes that AVAM is really a scam to “get on the phone with anyone I admire.”)

A groovy wall of shoes.

Each event and exhibition is always in line with the spirit of AVAM. Hoffberger has always stayed true to her vision, never following trends that come and go in the art world. With shows like the current The Secret Life of Earth: Alive! Awake! (and Possibly Really Angry!)—a large-scale art and science exhibition on climate change, up through September 6—it might seem like the process of conceptualizing such shows would come through intense examination of the world and what is happening in it. But she says the inspiration from her shows actually comes from another place.

“I pray,” she says. “It might sound old-fashioned, but I always pray for what to do. I do an inner begging to ask what will be the most worthwhile show. I have a great imagination, but these come from the Super Intelligence.” What’s fascinating about her process is the synchronistic way exhibits have coincided with world events. For instance, as Hoffberger was installing the show The Art of War and Peace, 9/11 happened. She opened Holy H20: Fluid Universe in the fall of 2004—just two months before the Boxing Day Tsunami, the deadliest tsunami in history, hit Indonesia.

“There really is a dance with something,” she says.

Ken Skrzesz, executive director of the Maryland State Arts Council, says visitors can sense that dance. AVAM is one of his “go-to places” to take out-of-town guests. “There is an inherent accessibility about AVAM,” he explains. “Various guests have commented how thought-provoking their visits have been.”

“I pray. It might sound old-fashioned, but I always pray for what to do. I do an inner begging to ask what will be the most worthwhile show.”

The museum has garnered praise from The Economist, CNN, and The New York Times, among others. The Washington Post called it “offbeat genius.” Travel + Leisure named it as one of its “10 Places to See Before You’re 10.” It was No. 1.

“You try to have something delicious for tiny kids who can’t read and for Nobel Laureates and everybody in between,” Hoffberger says. “I’ve been inspired by every artist, every member, everyone who brought people they love there, the people who say they’ve been going to the museum since third grade and now they’re getting married there. . . . It’s been such a privilege to take everything that ever touched my heart and put it in one place, like a banquet of fascination and beauty.”