The Maryland Film Festival starts tonight and goes through May 11. For true cinephiles, this is a clear-your-whole-weekend, turn-off-your-cellphones kind of event. Here’s a review of some of the great titles they’ll be screening. (With more to follow hopefully, if I can squeeze a few more in.) For a complete festival line-up, go to md-filmfest.com.

Club Sandwich

Club Sandwich is about that awkward time in a boy’s life when his arm pits begin to smell funky, the tiniest bit of fluff shows up under his nose, and all he can think about is sex. But what if that young boy has been raised by a single mother—a cool mother, with an eyebrow piercing, a skimpy bikini, and a tangle of string bracelets around her wrists? Suddenly the nature of the mother/son relationship takes on a different feel.

It’s at this crossroad that we meet young Hector (Luco Giménez Cacho) (they never specify his age, but he seems to be around 15) who’s staying at a nearly empty vacation resort with his sexy mom Paloma (the Frances McDormand-esque Maria Renée Prudencio). They spend long drowsy hours by the pool, each plugged into their iPods, or in their hotel room, ordering room service, watching TV, popping (his) zits, and rubbing each other with suntan lotion. If Hector were maybe just a year younger, the physical intimacy between them would be nothing out of the ordinary. As it is, a palpable (read: Oedipal) shift has occurred—possibly without either of them knowing it.

Into this mix comes Jazmin (Danae Reynaud) who’s staying at the hotel with her ailing father and his new wife. Jazmin is as frankly curious about sex as Hector is and they start hanging out, both clearly ready to experiment with each other. Paloma understands what’s happening and—although she gives Hector her tacit blessing (they even discuss condoms)—she’s jealous. In one of the film’s best scenes, Hector and Jazmin are drifting side by side in the pool, holding hands. From out of the frame comes Paloma, crashing into the pool, cannonball style.

Mexican director Fernando Eimbeke has created a film that is wonderfully insightful and droll. The film’s lazy tempo matches the torpor of its bored, sweaty, slightly restless characters. There are long stretches without dialogue where we just hear ambient noise—a nearby fan, the clinking silverware, an old English-language movie playing on TV. Eimbeke lingers over body parts, particularly from the perspective of Hector, whose encroaching puberty is like some sort of alien invasion. At just over 80 minutes, Club Sandwich is a marvel: A tender, personal film that evokes a very particular place and time, with great sensitivity and economy. (Screens May 9 and May 10)

Freedom Summer

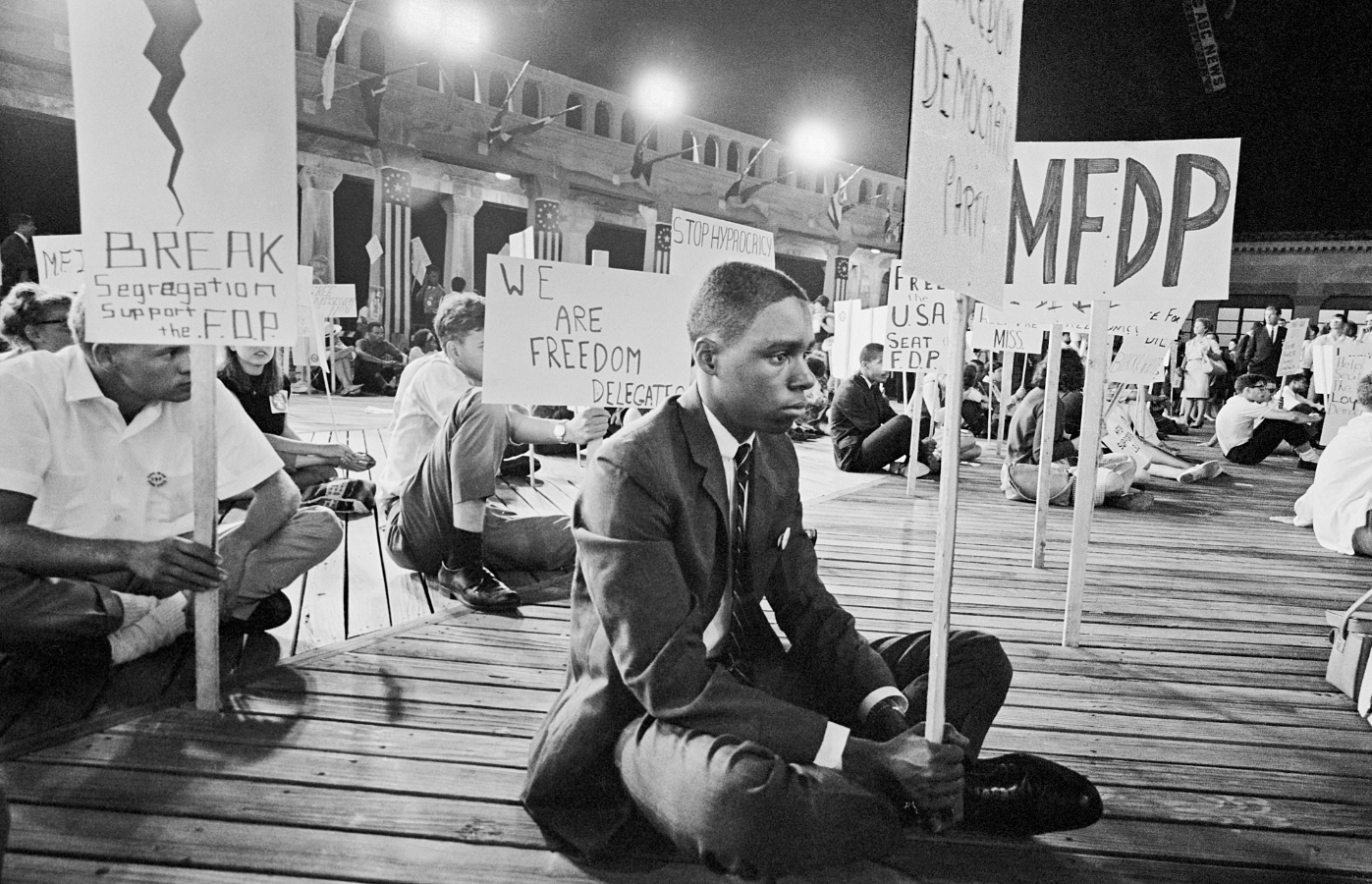

Riveting, inspiring, and beautiful documentary about the so-called Freedom Summer, when 700 student activists, most of them white, traveled to Mississippi to register voters and protest unfair voting laws.

Through interviews with surviving activists, plus archival footage, and stunning black and white photography, director Stanley Nelson gives you an up close and highly anecdotal sense of what that experience was like for its participants, many of whom were “embedded” in the homes of poor black families.

Technically, voting in Mississippi was legal for all races at that time, but in law only. Blacks who registered to vote were subject to losing their jobs, losing food bank privileges, or much worse. Those who got as far as the registrar’s office were deterred by the kinds of difficult questions that might’ve baffled a constitutional scholar.

We’ve all heard about the three young activists—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner— who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi that summer, but I had never heard it from the perspective of one of the Mississippi residents who remarked that, once they started killing white kids, she realized nobody was safe. After the three activists died, the leaders of the Freedom Summer allowed the participants to reassess their participation and go home. Few did. They were dedicated, passionate about their cause. (The film, inevitably perhaps, makes you long for the kind of communal spirit that grows from such activism.)

Although Lyndon B. Johnson is credited for signing the Voting Rights Act, he is depicted as a slightly petty man here. First, when the widow of slain activist Michael Schwerner comes to visit him, he describes her as “ugly” and “mean” to a confidante. (The film takes full advantage of the Johnson phone recordings that are now available to the public.) Johnson also saw the youth’s activism as a direct threat to his re-election. When the Freedom Summer participants descended on the 1964 Democratic National Convention in the hopes of replacing the all-white Mississippi delegation, they brought a secret weapon: Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper and a stirring, poignant voice for the rights of voters. What Johnson does to attempt to silence Hamer’s voice is a bit of absurdist political theater that I’m amazed I’d never heard about before.

I thought I knew a fair amount about the events of the Freedom Summer. This unforgettable documentary proved that my own knowledge had barely scratched the surface. (Screens May 8)

The Mend

John Magery’s The Mend starts with a burst of pure id: Ne’er-do-well Mat (Josh Lucas, scruffy, edgy—positively obliterating type) goes to visit his girlfriend Andrea (Lucy Owen). He says hi to her kid, he and Andrea have furtive sex, and moments later Andrea is screaming at Mat over some unseen offense, kicking him out. As a punkish tune blares obtrusively on the soundtrack, Mat goes spilling onto the streets of New York, bumming cigarettes, eating pizza, having a drink thrown at him at a café, until he finally ends up at the home of his brother Alan (Stephen Plunkett, pictured), who’s having a party.

This is a pivotal time in Alan’s life. A lawyer, he’s about to go on a vacation where he’ll ask his dancer girlfriend Farrah (Mickey Summer) to marry him. This is not spontaneous, the two planned it that way. But things aren’t going well between Alan and Farrah. They want different things—very different things—from sex. Plus, Alan is jealous of Farrah’s boho dancer friends and she resents how he’s always flaunting his superior education. The party goes on. Alan and Farrah trade snipes and power-plays and longing looks of jealousy. It’s into this somewhat contentious mix that Mat arrives, mostly looking to get high, complain about the guests, and possibly get laid.

The next day, Alan and Farrah leave and Mat stays (unbeknownst to Alan). Andrea and her son show up (she and Mat have made up, also off-camera; one senses these explosive blowups are not exactly uncommon between them), they move in, and then Alan comes back, alone, not wanting to talk about it.

You might expect Alan to instantly kick his brother out, but he doesn’t, partly because he likes Andrea and partly because he’s too depressed to do much of anything. Eventually, the power in the building goes out. Alan gets beaten up. People cut themselves on broken glass—twice. At one point, Alan and Mat drunkenly roam the streets, tormenting people along the way.

The Mend is about many things (too many, to be totally honest—I could’ve stayed at that effed up party for the entire film), but it seems mostly interested in our tenuous grip on civility. Mat has rejected civility on purpose. Mat and Alan’s uncle (Austin Pendleton) talks glowingly about the hippie ethos of living in your own stink for days. Without power, a primitiveness of sorts has set in at Alan’s apartment. A sense of unreality, too.

Magery directs his film with a kind of free-flowing bravado: The music, mostly avant-garde stuff, is intentionally jarring, disruptive—it calls attention to itself. Scenes begin and end in abrupt ways. In that sense, the film sometimes recalls the visual style of genius punk auteur Michael Haneke.

Josh Lucas anchors the film with his snarly, brilliant, incongruously sexy performance as Mat. He doesn’t so much give a performance as unleash one. It’s riveting stuff. The film is, too. (Screens May 8 and May 10)

All photos courtesy The Maryland Film Festival