Fall Arts

Spirit of Appreciation

Art collectors Claribel and Etta Cone left Baltimore with one of its greatest gifts.

Above: Etta Cone, Gertrude Stein, and Claribel Cone in Italy, 1903. COURTESY OF THE BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART

Henri Matisse's "Blue

Nude," the "Pink Nude."

O ne enormous nude painting might seem enough for a single narrow room, but when Henri Matisse’s “Large Reclining Nude,” also known as the “Pink Nude,” arrived at the adjoining Marlborough Apartments in Bolton Hill that Etta Cone had shared with her late sister, Claribel, she knew better. She hung it directly across from her sister’s “Blue Nude.”

One shockingly brash and blue, the other pink and striking in its simplicity, the two figures faced each other, reclining, both examples of a 20th-century master at work. Painted by Matisse nearly 30 years apart, the “Blue Nude” and the “Pink Nude” form a perfect set, and a fitting reflection of their owners.

The first was purchased by Dr. Claribel Cone in 1926, and the second by her younger sister, Etta Cone, a decade later. Each painting was outrageous in its own right—during a 1913 tour in Chicago, the “Blue Nude” was burned in effigy—and the aging, unmarried sisters, still bedecked in Victorian fashions as skirts got shorter and heels got higher, hardly looked like trendsetters. And yet, their purchases—and their predilections—were decades ahead of their time. What were once viewed as “strange” and “repulsive” pictures are now the crown jewels of the Baltimore Museum of Art’s collection.

When the “Pink Nude” arrived at the Eutaw Place apartment building, it entered a sort of avant-garde hoarder’s den. Bathrooms became small galleries under the Cone Sisters’ care, and mountains of works on paper by the likes of Picasso and Matisse were stacked in boxes or hung on the wall. A favorite painting was not insured, but hidden under the bed on occasion. For Claribel and Etta, more was more. And thank God for that.

“Claribel and Etta are within a long line of marvelously philanthropic Baltimore women, amazing women, who have come out of Baltimore and led fascinating lives, and we know of them really through the art they left behind,” says former chair of the BMA board Stiles Colwill.

“Claribel and Etta are within a long line of marvelously philanthropic Baltimore women...and we know of them really through the art they left behind.”

Today, it’s hard to imagine the BMA without the Cone Wing, which houses some of the best examples of modern art in the world. But it had to earn it. The Baltimore that existed between the World Wars was conservative to the point that Claribel used her will to call out what she saw as a lack of vision: “It is my suggestion, but not a direction or obligation upon my said Sister, Etta Cone, that in the event the spirit of appreciation for modern art in Baltimore becomes improved . . . that said Baltimore Museum of Art be favorably considered by her as the institution to ultimately receive said Collection.” In short, unless Baltimore learns to appreciate it, send the whole lot elsewhere.

Luckily, that spirit of appreciation for the Cone Collection, and the sisters themselves, missing at the time of Claribel’s death in 1929, has grown to canonization. But it was a long time coming. Even longer for Etta, who was for decades characterized as a purchaser of “pretty paintings” in contrast to her sister’s proclivity for bold moves and major purchases.

“I find the Cone Sisters to be an incredible model and inspiration for the future of Baltimore,” says Cara Ober, the founding editor and publisher of BmoreArt. “These were collectors who invested for a lifetime in the artists they believed in . . . who weren’t particularly famous at that time. As a result of their patronage and support, these artists became the world-renowned figures that they are today. [The Cone Sisters] were visionary risk-takers who invested in the artists they personally believed in, and this belief was a catalyst for the worldwide success of these artists, and the reason that the BMA is host to a spectacular and world-class Matisse collection.”

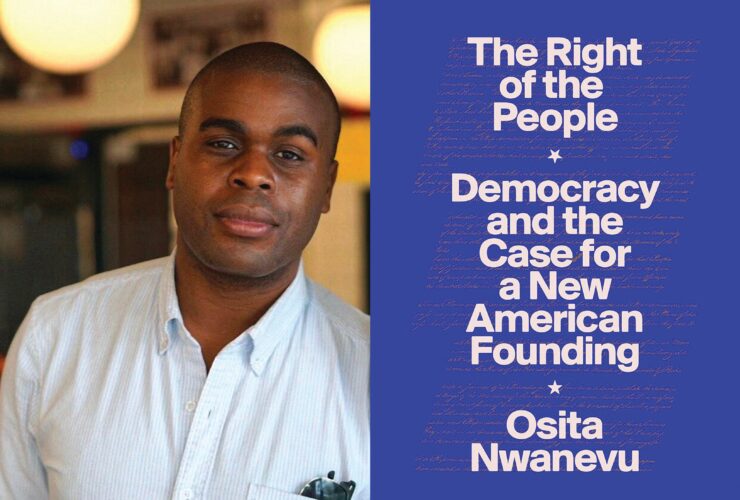

Now, that collection is the subject of a new exhibition, A Modern Influence: Henri Matisse, Etta Cone, and Baltimore, covering scores of paintings, sculptures, and works on paper that track the development of Matisse as an artist and Etta as a collector. Final touches are also being put on the long-awaited Ruth R. Marder Center for Matisse Studies at the BMA, opening in December. Built around Claribel and—especially—Etta’s collected works, the Center for Matisse Studies will position Baltimore as one of the premier places in the world to study and engage with the artist’s work.

The collection they built together tells the story of two women who placed tremendous value in promoting new ideas, celebrating revolutionary artists, and forming an archive of a time period that we would come to know as one of the most exciting creative eras of the past few centuries. And in the end, much to the delight of decades of Baltimoreans, they decided to give it to us.

Arts & Culture

Your Guide to the 2021 Fall Arts Season

It’s been entirely too long, Baltimore. Here are the can't-miss arts happenings in the months ahead.

THE CONES OF BALTIMORE

The Cones came to Baltimore in May 1870, following a successful stint in the clothing business in Tennessee. Herman Cone (born Kahn) of Germany and his wife, Helen, arrived with seven children and one on the way, hoping to grow a business in the more metropolitan area and find a home in its expansive German Jewish community. Claribel was 5 when the family relocated, and a few months later, Etta was born. Helen and Herman would have a total of 13 children, and the sisters would call the city home all their lives.

While the sisters were pursuing their respective educations—Claribel studied at the Women’s Medical College of Baltimore and then Johns Hopkins and the University of Pennsylvania to become a physician; Etta attended the public Western Female High School before taking over running the Cone household—their brothers Moses and Ceasar handled much of the Cones’ business pursuits. They expanded the family wholesale goods business, gaining a foothold in the booming textiles industry. When Herman died, his shares in mills and factories across the South, as well as some provided by their brothers, went to the unmarried Claribel and Etta. This steady income offered comfort, and more importantly, freedom. Bucking the expectation of their time, neither would marry in order to gain financial security. They could pursue the great loves of their lives—art, travel, education—instead.

While both were excellent students, it helped them to have a good introduction to the rarefied world of art and collecting. And there were perhaps no better guides than the Stein family. Soon-to-be literary luminary Gertrude Stein and her art-collecting brother, Leo, became dear friends and regular visitors to the Cone family home upon their arrival in Baltimore. The Steins knew culture better than most, and the sisters would take some collecting cues from them for decades.

The Cone Sisters.

Though her formal education ended in high school, Etta was a devoted student of art and history. Even before her visits to Europe and serious forays into collecting, Etta’s eye was well ahead of the world around her. The first paintings she ever bought, five small oils by American Impressionist Theodore Robinson, were chosen before Etta ever traveled to Paris, and before even those deeply entrenched in modern art circles were pursuing similar works. In fact, the oils were housed in the BMA basement for decades, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that Robinson’s work found wider appreciation.

Nancy Ramage, the great-great niece of the sisters and an art historian based in Ithaca, New York, grew up hearing stories of Etta and Claribel from her mother, Ellen Hirschland. Hirschland, née Berney, was devoted to her great-aunt Etta, and traveled with her in her youth. Hirschland, who passed away in 1999, and Ramage have contributed several books and articles to the study of the sisters and their collection.

“[Etta] was kind of the intellect behind this collection, and she’s the one who started collecting,” says Ramage. “Claribel wasn’t the least bit interested in painting or art at first. She was studying medicine and doing pathological work. But Etta was out there making choices, especially those Robinsons she got, the first paintings that she bought, that were just remarkable. She was so far ahead of her time.”

Etta absorbed everything she could about the history of art, first on her own, and then under the tutelage of the Steins, who were living abroad in 1901 when Etta first traveled to Europe. She toured Florence with Leo and spent long days with Gertrude in Paris visiting galleries, museums, and shops. Etta returned to Baltimore with new art pieces and a growing passion for collecting. When, at the end of the next year, her mother died, Etta, then 32, found herself free of familial obligations, well-connected, and wielding an income of her own. She set sail for Europe with Claribel the following summer.

A MATTER OF TASTE

Throughout the first decade of the 1900s, the sisters traveled back and forth to Europe, studying art, spending time with the Steins and their circle of friends, and, for Claribel, conducting medical research in Germany. Etta found time to type the manuscript of Stein’s first novel, Three Lives, and entertain a marriage proposal from Mahonri Young, grandson of Brigham Young. (It didn’t work out.)

On a 1905 visit to Paris, the sisters attended the Salon d’Automne, where they got their first true look at avant-garde art. Slashes of color and inexact forms filled a room, including Matisse’s “Woman with a Hat,” a colorful portrait featuring bright teals and an unfinished quality, which Leo Stein called “the nastiest smear of paint” he had ever seen. (After some consideration, he and Gertrude bought the painting, which now hangs in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.) Leo later took Gertrude and Etta with him to visit a young, Spanish unknown who had shown works at the Salon, and soon both the Steins and the Cone Sisters were regular visitors to Pablo Picasso’s Paris studio. They often purchased his drawings, partially out of charity to the starving artist—this was a habit of Etta’s in particular; she also supported struggling MICA students back home—but also because they admired his work. (They never purchased anything without what Ramage and her mother described as “great care and a sureness of taste.”)

“Etta had phenomenal taste,” says Ramage. “The fact, for instance, that she bought so many drawings over the years . . . they’re not splashy, but they’re incredibly valuable and descriptive of the thinking of the artist. I don’t just mean the Picassos she bought on that first visit when she was maybe doing some charity work, but throughout her life, she bought drawings and engravings and prints that are sensitive and very important works.”

It wasn’t long after that monumental Salon that Etta met Henri Matisse, the artist who would become a constant friend and influence for the remainder of her life. After the Salon d’Automne, Matisse could often be found at the Stein apartments in Paris, one of the few places where his work was displayed. In January 1906, Etta began acquiring works by the 36-year-old painter. It is worth noting that it took many years for Matisse to earn the respect of the art world at large. Even seven years later, when Matisse’s works were loaned to the Armory Show of 1913, a critic panned the artist’s contributions as “the most hideous monstrosities ever perpetrated in the name of long-suffering art.”

But still, Etta remained a staunch supporter, and as Claribel discovered her own interest in collecting, she too began acquiring nontraditional pieces with marked enthusiasm. The elder Cone sister has often been credited for the collection’s quality, but the sisters’ contributions were simply different.

“Certainly [Claribel’s] purchase of Matisse’s ‘Blue Nude’ changed the tenor of the collection entirely,” says Katy Rothkopf, senior curator of European Painting and Sculpture at the BMA and Anne and Ben Cone Memorial Director of the new Center for Matisse Studies. “It had effects throughout the art world. With her purchases she made these big statements.” Etta made bolder, splashier purchases later in life, but she had a strong eye for smaller works, especially when it came to Matisse. “She really got into all of the media and was fascinated by all of it.” Rothkopf says. “That’s really her legacy.”

Katy Rothkopf

will head the new

Center for Matisse

Studies as Anne

and Ben Cone Memorial

Director. Photography by Mike Morgan

The sisters spent years gathering modern pieces, filling their rooms at the Marlborough Apartments to the point that Claribel chose to sleep on a lower floor rather than relocate her collection. They educated themselves, attending lectures at Johns Hopkins and forming relationships with artists and dealers across Europe.

One of their tutors, Professor George Boas, wrote of the sisters after their passing: “Does one need much imagination to see the courage it took for two young women to spend their allowances on such strange, repulsive, and clearly insane pictures as those of Matisse and Picasso? I can well recall how, on coming to Baltimore in 1921, I was warned that, of course, I might visit the Cone Collection if I wished, but that its owners were beyond doubt mental cases.”

The advice Boas received was the prevailing opinion among the locals at the time. But the sisters kept collecting, and by the time Claribel died in 1929, she had amassed scores of paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and other art objects. And she left them all to Etta.

CRAFTING THE COLLECTION

With Claribel gone, Etta’s mission was set. It was her duty to steward the now combined Cone Collection, keeping it together, filling in its gaps, and determining its future. Whereas Claribel had enjoyed the art and business of collecting, Etta had a solid sense of her own taste and an unmatched ability to recognize potential. She began to seek out items that could bolster areas she felt were lacking and emphasize the strengths in the collection.

When the Claribel Cone Memorial Catalogue, the first archive of the Cone acquisitions, was published in 1934, the select few with access to the volume were amazed at the quality and quantity of the work. Boas, who wrote the foreword, was already emphasizing the collection’s importance as a retrospective of Matisse’s artistic life, and Etta had yet to make several major purchases of the ’30s and ’40s, the “Pink Nude” among them.

Matisse himself also seemed to realize the potential of the collection as part of his own legacy. He spoke of a future Cone Museum, and is said to have specifically advised Etta on pieces that would mesh well with other works of his in her collection. And when he visited Baltimore in 1930, Matisse personally cleaned up one of his paintings at the Marlborough with water and Ivory soap. That visit would also have been the first time in years he had seen many of his works, including Claribel’s most monumental purchase, his “Blue Nude.”

“When he came in 1930, he saw the ‘Blue Nude,’ which he may have not seen for quite some time,” Rothkopf says. “And not so long after, he started to work on another version of a reclining nude, but in another shade. I think he wanted to have those two works live together forever.”

Etta’s relationship with Matisse was not only a partnership between artist and patron, but a genuine friendship. Their correspondence and records of their visits reflect genuine interest in one another’s lives and families. When Etta came to France in 1933, Matisse was too ill to leave his bed, but still insisted that Etta visit his home. After chatting a while, the artist asked Etta to turn around. Sitting in front of the window was a model in a yellow outfit, the living image of Matisse’s “The Yellow Dress,” which Etta had purchased the previous year—a sweet gesture meant only for her enjoyment. Later, Etta would send one of Matisse’s grandsons, Claude Duthuit, a brand new, red Schwinn bicycle. When World War II hit France, that bike became the family’s lifeline, allowing young Claude to travel across Paris for bread rations.

Throughout most of the 1930s, Etta made it a habit to collect at least one major Matisse a year, and nearly a quarter of his entire output as a sculptor would make its way into the Cone Collection. His “Pink Nude” seems to have never been intended for anyone but Etta. From September to November of 1935, Matisse sent more than a dozen photos of the work in progress to Baltimore. When Etta arrived in Paris the next summer, her niece Ellen in tow, Matisse showed them the final work.

“I was present when Matisse first showed Etta the ‘Pink Nude,’” wrote Hirschland in The Cone Sisters of Baltimore. “I believe he especially wanted it and “Blue Nude” to be shown together. When Etta bought the new painting, she hung it in Claribel’s ‘Blue Nude Room,’ where the two faced each other . . . Matisse would have been astonished to see that these two colossal paintings were displayed in such small quarters.” It’s not hard to imagine that Claribel, who enjoyed the shock her nude elicited from visitors on its own, would have been delighted.

MORE THAN MATISSE

The Cone Collection houses some of the best examples of modern art in the world, and both sisters made purchases that highlight artists at unique moments in their careers. There are plenty of Matisses to be found in A Modern Influence, but make plans to visit these works by other artists when they're on view in the Cone Wing.

COURTESY OF THE BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART

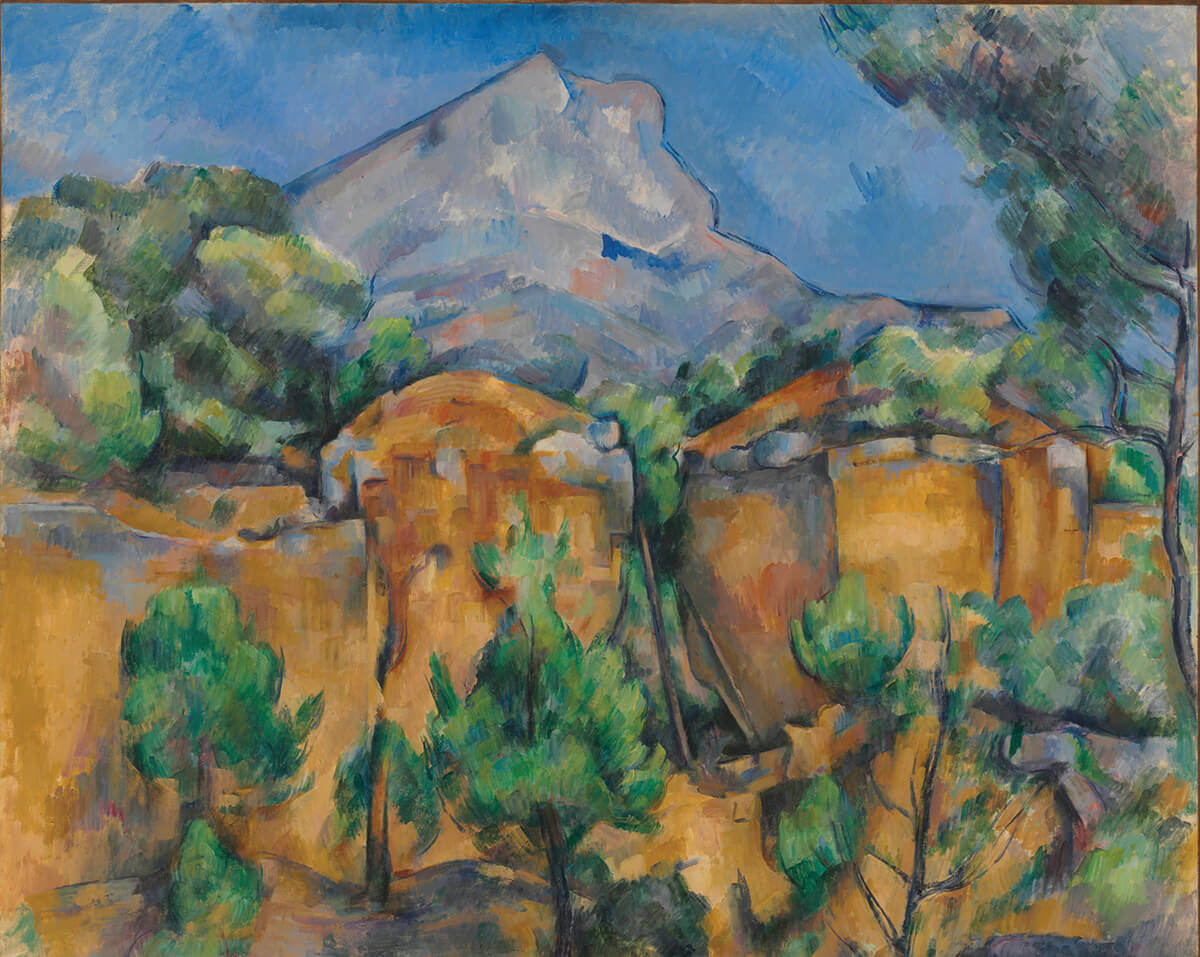

MONT SAINTE-VICTOIRE SEEN FROM THE BIBÉMUS QUARRY

Paul Cézanne Purchased by Claribel Cone in 1925

Claribel purchased this painting, one of dozens of studies Cézanne did of Mont Sainte-Victoire, for 410,000 francs, the highest amount either sister ever paid for a painting. It was hung prominently in Claribel’s apartment at the Marlborough, and even after her sister’s death, Etta refused to move the favored piece.

A PAIR OF BOOTS

Vincent van Gogh Purchased by Claribel Cone in 1927

Among those items purchased through Paul Valloton was this Van Gogh still life from 1887. At the time of its purchase, the market for the artist’s work was booming, and there were many fakes in circulation. Indeed, Etta’s purchase of a “Van Gogh” was later discovered to be a fake, but this example was provided to Claribel by Valloton sans doute.

MOTHER AND CHILD

Pablo Picasso Purchased by Etta Cone in 1939

Picasso’s “Mother and Child” is the last painting that Etta bought from art dealer Siegfried Rosengart, a relationship that facilitated many of her purchases throughout the ’30s. The painting, from the artist's “classical period,” made it across the Atlantic shortly before World War II shut down international shipping.

VAHINE NO TE VI (WOMAN OF THE MANGO)

Paul Gaugin Purchased by Etta Cone in 1937

This 1892 masterpiece was painted during the artist’s time in Tahiti and features his mistress, Tehaurana. Before Etta saw it in 1937 and fell in love, it passed through the hands of artist Edgar Degas and relatives of Edvard Munch.

THE LIE

Félix Vallotton Purchased by Etta Cone in 1927

Daring in its subject, this bright and intimate scene of two lovers was purchased by Etta through the artist’s brother, the art dealer Paul Vallotton. Though Etta did not like Paul, she and Claribel bought several pieces from him, including an ancient cat and many paintings, in the 1920s.

A LASTING LEGACY

Once the catalogue was distributed, the Cone Collection, and Etta, were raised to new heights. It was well known in art circles that the collection was to be kept together, and museum directors from across the country courted Etta for her bequest. The BMA’s first curator of prints, and later director, Adelyn Breeskin, took it upon herself to make the case for Baltimore.

“Along came Mrs. Breeskin, and she really worked on Etta for years in a fawning way,” says Ramage. “One of her most important aims as director of the BMA was to persuade Etta to give that collection to the museum . . . and credit where credit is due, she really put Baltimore on the map in terms of art by getting this collection. It made [the BMA] into one of the great American museums.”

Etta Cone died peacefully at her relatives’ estate in North Carolina in 1949 at the age of 78. She was brought home to Baltimore and interred alongside Claribel in the family mausoleum at Druid Ridge Cemetery. Ever practical, Etta included in her will a bequest of $400,000 to the City of Baltimore for the construction of a new wing to house the Cone Collection, in addition, of course, to the collection itself. Rising costs meant that the sum only covered part of the bill, but with some help from the City, the new Cone Wing opened in 1957. In 2001, it was overhauled into the version we know today, and its value was reported to be around $1 billion. The Center for Matisse Studies, in the works for decades, is the newest addition to the Cone footprint at the BMA.

Rothkopf says the museum hopes to create a place where the community can engage with Matisse's work in a whole new way.

“We’re adding a lot more space to provide access to the collection to more people, which is a wonderful thing,” says Rothkopf. “We have a small gallery where we will focus on works on paper that normally aren’t seen by our visitors. My plan is for the first year to focus on just Matisse, but it’s a place where we can do experimentation and innovation.”

Though it isn’t a Cone Museum as Matisse imagined, in the end, it is something akin to what both he and Etta might have envisioned for their partnership: a singular place where visitors can study and enjoy the works he entrusted to the sisters a century ago. Further works from the Marguerite Matisse Duthuit Collection, provided by Claude on behalf of his mother, Matisse’s daughter, will also be included. Those, too, Etta had a hand in.

On a trip to New York in 2010, Colwill and now retired BMA curator (and inaugural Center for Matisse Studies director) Jay McKean Fisher were visiting with Duthuit and his wife, Barbara. At one point, Claude left the room and returned with a stack of matted prints. “He came back with an armful,” says Colwill. “And he said, ‘These are very special. . . . Each of these prints is inscribed by Matisse to my mother.’

“He said, ‘With these, we would like to establish the Marguerite Duthuit collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art, because my mother, her best friend was Etta Cone. And I think my mother would be pleased to know all of these things were going to the museum to be with her best friend’s things.’ And Jay and I walked out with over 250 Matisses.”

The opening of the center is the culmination of a decades-long vision that spans the tenures of multiple BMA directors, including Doreen Bolger, who was responsible for the 2001 renovation. Now that it’s finally coming to pass, Rothkopf says the museum has already heard from museums both in the U.S. and abroad who hope to partner with them in new ways through the center.

The Cones’ legacy is also still being felt by current collectors. Ober says the sisters have been inspirational in BmoreArt’s focus on talented artists in Baltimore, beyond the traditional “market-validated” New York gallery artists, particularly via Connect+Collect, which educates collectors about how to invest in the art of their own place and time and build lasting relationships with artists. “The Cone Sisters have proven that it is relationships that build a healthy market for art, and this is something Baltimore’s artists need and deserve,” Ober says. “It is my hope that the actions of the Cone Sisters—pure, reckless speculation and love for artists— inspires a new generation of collectors in Baltimore who also want to collect the art of their place and time and catalyze success right here in Baltimore.”

That spirit of appreciation that Claribel sought has arrived in spades, and the works the sisters were so ridiculed for purchasing have made Baltimore a destination for art lovers around the world. If all goes to plan, the new Center for Matisse Studies will attract even more visitors to see the priceless gift that Claribel and Etta gathered for us all. The experience of the Cone Collection is one Boas summarized best in his own catalogue.

“One went to see the Cone Collection,” he wrote. “One came away with a vivid image of two beautiful people.”