Arts & Culture

The Puppet Master

During her three-decade career, Connie Imboden has found inspiration by channeling her unconscious.

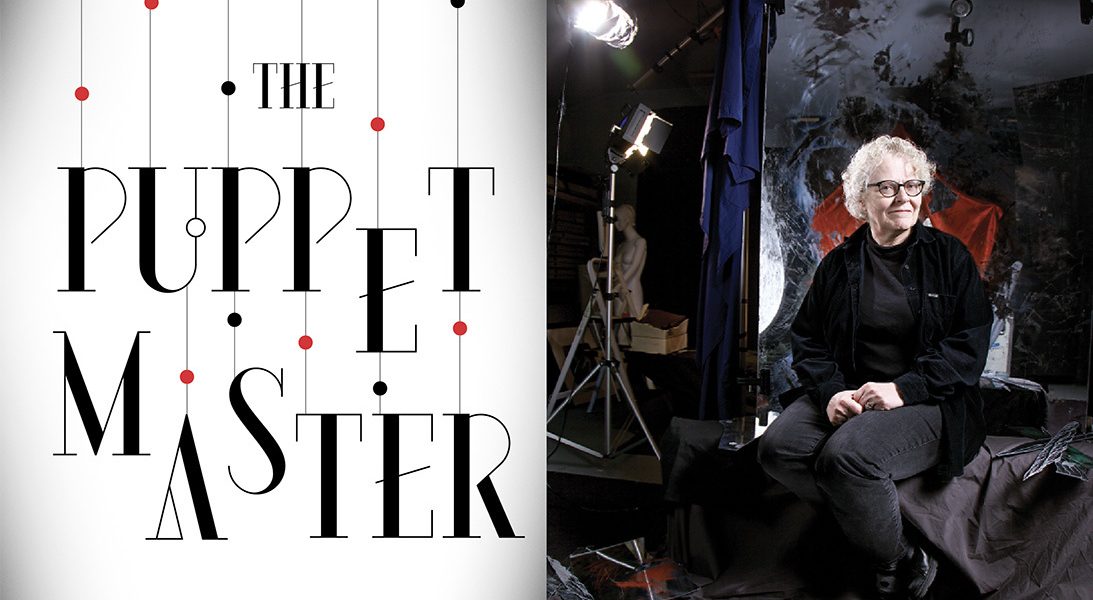

A cacophony of construction greets me as I enter Highlandtown’s Y:ART Gallery: the ripping of bubble wrap, the clatter of ladders, and the thumping of hammers. All this announces, before I observe a single frame on the stark white walls, the installation of a new show by world-renowned local photographer Connie Imboden, which is the first time her work is on display in Baltimore in 13 years. I spot the artist standing nearby, and surprisingly, she seems immune to all the commotion. She watches patiently, draped in her customary all-black attire, as Connie Imboden: A Retrospective comes to life. Instead of appearing stressed or anxious, she is gracious and enthusiastic as she dashes up to me and reaches for my arm. “Let me show you what I’ve been talking about,” she says.

Imboden leads me through a hallway lined with frames leaning against the walls to an open room. We walk to the far wall, and she turns toward a smaller photograph that is resting on the floor. Imboden watches me as I take it in. In this work, a man gazes downward, with one of his arms loosely extended above his head, an eerie red light illuminating the background. It has a decidedly classical feel, with rich color and detail, and as with the rest of Imboden’s work, it seems almost impossible that the image is a photograph.

“It’s beautiful,” I tell Imboden. “It makes me think of those paintings from the Renaissance, where Jesus is being taken down from the cross.” She smiles. I would come to understand that this way of engaging with an observer is typical of Imboden, who, even after a more than 30-year career, still craves discussion and new stimuli. “This is my favorite, I think,” she says. “I still don’t know what he reminds me of, though. Something . . .” She rubs her fingers together, searching for words.

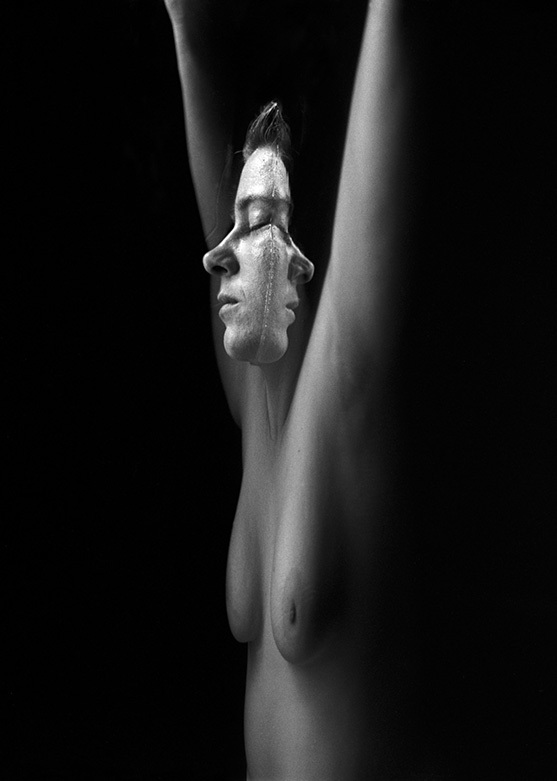

Her reverie is broken by Juli Yensho, Y:ART’s owner, who has a question about the placement of a piece. I take a moment to peer across the gallery at the beginnings of Imboden’s show, which spans a career that has placed her work in collections including The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. There are early prints, where faces float in water surrounded by the reflections of finger-like trees, and her more abstract, midcareer works where body parts—feet, breasts, torsos—serve as sculptural elements. Imboden’s latest photographs, where figures are shot through scratched mirrors and imbued with color, stand apart from the rest, but it’s easy to see a connecting thread—all of the images dance between this world and another, playing with our perception of reality.

Imboden catches me a few minutes later, toward the front of the exhibition. She’s still thinking about her favorite piece, she says, and wants to share more insight. “I think what makes it so special is that he seems like a puppet,” she says, “like he’s being controlled by an unseen force.” She gestures toward a print in which a dark form looms over a face submerged in water. “This is one of my earlier works, and you can see how that thread connects here. And I think in many ways, I see myself that way as an artist. Like I’m a channel for a higher power.”

I didn’t realize it then, but I would soon learn how this concept has propelled her career. How it has shaped her from a young woman exploring her identity to a confident, focused artist who, despite the fickleness of the art world, has stayed true to her passion. And how her exploration of this belief of artist as medium has allowed Imboden, once again, to reinvent herself and create some of the best art of her career.

Though it was a year filled with political and social turmoil for most of America, 2016 was a good year for Imboden. “Really, really good. I haven’t had a year like this since the late 1980s,” the 63-year-old artist says, which is a statement that speaks as much to her longevity as to her recent success. “I guess I was ready, I was due.”

We’re sitting in Imboden’s two-story studio that she built next to her house in Ruxton. Upstairs is her shooting space, where a large piece of mirrored Plexiglas stands in the middle of the room. Downstairs are Imboden’s and her assistant’s desks. Imboden constructed these buildings on land that was a gift from her mother and they stand adjacent to her childhood home. When you arrive at the hilltop spot, you leave the bustle of the highway and enter an artist’s enclave, complete with whimsical sculptures that line the winding driveway. The property is idyllic, with beautiful trees, delicate stone paths, and a tiled pool, where Imboden takes her water photographs. This setting stands in stark contrast to the dark, challenging photos that have resulted from these sessions.

Imboden, too, is different in person than her work might suggest. She’s light-filled, warm, and engaging. She isn’t afraid to dive into deep topics, exploring the meaning of her work, the difficulties of the art world, and the source of her inspiration. But this is leavened by a keen sense of humor—for example, she jokes to me that it’s nice to have some space between her and her neighbors, especially during night shoots with nude models.

Imboden’s latest creative burst started when her wife, Patricia Dwyer, took her to see a live broadcast of the opera Lulu. Though Imboden found Alban Berg’s music harsh and dissonant, she was blown away by South African artist William Kentridge’s staging, which evoked German expressionism. “The way that they portrayed [Lulu], the prostitute, as being naked on stage [was that] she was fully clothed, but they took a piece of paper and just drew a breast. And she was so naked, so raw. I’ve always been attracted to that period of time, when the angst expressed was so real. I was mesmerized.”

About a month later, Imboden began shooting her latest set of images, segmenting the reflection of a mannequin’s torso on her model’s body, playing with the placement of scratched fragments of mirrors, and adding colored fabric to the background to create an unearthly mood. When she looked at them later, “I thought, ‘Wow, here’s German expressionism,’” she says. It sparked an enthusiasm that was shared by others.

“What’s remarkable about her new work is what’s also remarkable about all her work—Connie is willing and able to photograph our fears and insecurities in an abstract way that makes us more willing to confront them,” says Arthur Ollman, the founding director of the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, who curated an exhibition of Imboden’s work there. It’s “not the usual way of making pictures of pretty bodies. Instead, she reaches below the surface of people’s beings and challenges us to recognize what we fear most. Her work is less about the body, and more about the psyche.”

“It’s really exciting to see what, for me, is the best stuff she’s ever done,” says long-time friend Susan Waters-Eller, who is an artist and professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). “Something really unique has emerged out of this vision that she’s propelled all these years. It’s amazing what you can get when you’ve been at something for so long.”

That support is what led to her retrospective at Y:ART. After a 13-year break from the local gallery scene, Imboden hadn’t considered showing her work in Baltimore. But a friend she’d gone to kindergarten with mentioned the year-old space, and after touring it—and feeling excited about her new work—Imboden thought, “Why not?” Yensho was thrilled. “She is such a dear person,” she says. “It is my hope to keep her star shining brightly for many years to come.”

What’s particularly amazing about Imboden’s art is that she often can’t explain where it comes from. For instance, I ask her how she knows that she’s created something that transcends, and she stops and thinks. “It kind of takes my breath away,” she says a moment later, “but I don’t know what it means. It reminds me of something but I don’t know what that is.”

She continues: “When I think of my work, there’s clearly a thread from the beginning to now. And I think that thread is the intuitive piece of it, the exploration of it and how that lends toward being a channel.”

Imboden first picked up on this concept in graduate school at the University of Delaware. One day during a critique—a process she hated—she put up a piece with a woman’s face duplicated by her reflection in the water. “And somebody said, ‘Oh it looks like a Janus face,’ and everybody else said, ‘Oh, it’s a Janus face.’ I had no idea who Janus was, but I found out he was the Roman god who was the gatekeeper, who looked forward and backward at the same time. I thought, ‘Wow, how could I make an image that is so resemblant of that god, not knowing who that god was?’ So I started exploring.”

Imboden's Spell (1986); Untitled #01-21-11-100 (2011); Untitled #09-04-13-287 (2013); and Dead Silences (1988), which her classmates referred to as her Janus work.

Imboden has always been given to exploration. But it wasn’t until she discovered photography at age 17 that her investigations began to bear fruit.

In her 2009 collection of photographs, Reflections: 25 Years of Photography, she writes that she was introduced to the art form by her mother. In the summer of 1970, before Imboden’s senior year of high school, Mary Sawyers Imboden handed her daughter a summer school catalog for MICA, with a basic photography class circled. “How my mother knew I should be a photographer is one of the great mysteries of life. Our family was full of doctors and bankers, but no artists,” she writes. “This suggestion of hers was seemingly out of the blue, but in reality was an intuitive insight. She knew 16-year-old me better than anyone else in the world (far better than I knew myself) and saw the latent creative energy waiting to be channeled.”

Photography came quickly to Imboden and “looking through the camera lens was a perfectly natural experience for me,” she writes. Soon, she was experimenting with the effect of water and mirrors on the human body, drawn to their warping perspective. She began to notice that her work felt psychological, reflecting her own fears and pain. Even her attraction to water had that element—she was terrified of its murky depths after almost drowning as a child.

“I think she had gone through so much with being gay, and trying to figure that whole thing out. And not feeling successful in the traditional sense in school [or] that she had a path. Then she started photography, and that just anchored her,” says Imboden’s wife of 12 years, Patricia Dwyer. “Some of those earlier pieces that are fractured self-portraits say a lot about what she was feeling as a young woman.”

Imboden noticed that her work had a cathartic effect. “When I was younger, I was just filled with heaviness, and through photography, I confronted a lot of the stuff that I felt like I couldn’t put into words,” she says. “It’s been through photography that I’ve been able to get in touch with this darkness that I know very well. . . . It seems that all I have to do is start photographing and darkness flows out of me. It still amazes me because I don’t feel the darkness, I feel kind of the opposite. But the darkness is still very much a part of me.”

It was also cathartic to find kindred spirits within Baltimore’s arts community. During the 1970s, she, Waters-Eller, and others formed the Women’s Art Community, which aimed to promote work of underrepresented female artists. Perhaps that artistic camaraderie aided in her analysis of intuitive insight, because she discovered Carl Jung and his explanation of the collective unconscious—his theory that humans share a portion of their unconscious minds, made up of latent memories from our ancestors and evolutionary past. “I was very attracted to his explanation of how art is created—a connection to ourselves, the unconscious, where we store all of the stuff that’s too uncomfortable to deal with,” Imboden says. “But it was also the possibility of connecting to something much larger.” Imboden’s attraction to this concept could itself be called an example of the collective unconscious at work—her father, John Imboden, was a psychoanalyst who was influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud, Jung’s friend and contemporary.

Armed with this knowledge, Imboden found new creative freedom, and out came works that resonated with larger and larger audiences, with solo exhibitions at institutions like the Centro de la Fotographia in Lima, Peru, and the Galerie Esther Woerdehoff in Paris. Waters-Eller attributes art patrons’ reactions to Imboden’s work as evidence of the shared unconscious. “It’s amazing how people respond to it,” Waters-Eller says. “I think people are encouraged by seeing things that remind them that there’s a lot more mystery than modern life would make us think.”

But Imboden knows well that the attention of art patrons can be fleeting. She first noticed the shift after Sept. 11, 2001.

“It was like our values changed, our aesthetic changed. Artwork has become much safer, not as challenging, and my work is obviously really challenging,” she says. “My work really started not selling, and I saw the trend go toward much softer images. It’s been frustrating to see how the art world has been turned into this commercial craziness, and the lack of serious work has really bothered me.”

At the same time, photography was making a major shift from film to digital, and art galleries started showing photography that had been manipulated in Photoshop. After years of cultivating skills in a darkroom, “I was really at the point where I could say I’m a master printer,” Imboden says. “And then, suddenly, it all went away.” (She did eventually make the switch to digital in 2007. She says she realized “if I have a tool that will allow [my images to be] better and stronger, why wouldn’t I embrace that?”)

Instead of changing her aesthetic, Imboden stuck to what she knew and found an audience. She began taking her work to Asia and Europe more frequently, and found success there, particularly in Scandinavia. “She has really stayed true to her vision, as different types of photography have come in and out of vogue,” says Dwyer, who met Imboden during this time. “And she believes in it so thoroughly and so deeply that she has to continue [down] the path that she is on. That takes a lot of courage. It would be so easy to go with the current trend, which would be quickly sellable, or picked up easily for this or that show. That would be a compromise for her, and that’s not what she’s willing to do.”

Though she was traveling increasingly, she still used Baltimore as her home base. And she remained devoted to cultivating its next generation of artists. In 2008, Imboden helped create the annual Baker Artist Awards, which are named for her mother’s family and are some of the city’s most prestigious art prizes. She also focused on teaching—at workshops in places like Norway, France, and the Czech Republic, and at MICA (though she stopped teaching there two years ago and has focused more intently on her work).

One such workshop was in 2014, in the United Arab Emirates, an assignment that surprised Imboden at first. “Here I am a woman, a lesbian, invited to this place where they don’t exactly like women,” she says. “But what was so cool was I showed a slideshow of my work to the class, and they didn’t ask any questions, but they listened. And I got all the way through to the end and the class said, ‘Would you do that again?’ I felt like that was the deepest compliment anyone had ever given me.”

This became another example to her of how we are all connected, whether that is consciously or unconsciously.

“It led me to understand the power of art and the importance of art in our lives. How important it is to have this common language where we can begin to share really deep emotions that sometimes transcend words,” Imboden says. “Then, we can gain shared empathy and compassion, [which] connect us rather than pull us apart.”

Examples like this sometimes surprise her. She smiles, thinking of another time. “I was having some electrical work done, and an electrician walked by and stopped to look at my works. He said, ‘Did you do this?’ I said, ‘Yeah I did this.’ And he said, ‘Good to get that stuff out.’” Imboden laughs. “That kind of says it, doesn’t it?”

It’s a weekday afternoon, days after her Y:ART show’s installation, and Imboden sits on a stool in the upstairs of her studio. She directs her long-time assistant, Cory Donovan (who is a Baltimore magazine contributor), on the placement of mirror fragments, which are then attached to the larger Plexiglas mirror. Her instructions are quite detailed—creating art is often more technical than it seems. “Try it with the ragged edge going down. Now go that way,” she says, her fingers duplicating her directions. “Stop right there.”

She instructs me to sit behind her so I can see what she sees. Then, her long-time model Carl Stevens disrobes and sits on a bench in front of her. Imboden has grown fonder of the collaborative process, and appreciates the energy of Donovan, who became her assistant while a student at MICA, and Stevens, an actor who lives in Florida. Stevens will “come for a few weeks, and we do these binge shootings,” Imboden says. “We’ll shoot for four or five days in a row.”

“You do something, and we’ll work with it,” Imboden tells Stevens. So he rotates his shoulders to meet the mannequin, the reflection of which he sees in the mirror. “Put your hand on your hip,” Imboden directs him. After many adjustments, Imboden holds the camera to her face and the gentle pulse of the shutter sounds repeatedly.

This is the moment when she believes that she becomes a channel for the unconscious. When she’s shooting, “I like to react to things. There’s a level of exploration, and that’s when it becomes a much more intuitive process. I’m concentrating so much on what I’m looking at that I don’t really have time to think,” she says. “Plato said when artists create, they’re out of their minds. And my interpretation of that is they put their mind away, and they’re present. They can go deep within themselves, and perhaps deep into a greater mind.”

At one point during the shoot, Imboden leans really close to Stevens, almost as if she is going to perch above his shoulder. She then peeps through the camera’s viewfinder. “Oh God, you look like you have wings and you’re going to fly!” she exclaims. She holds the camera in one hand and places the other just above Stevens’ shoulder—and I watch the puppet become puppet master. “Now move your arm up a little bit,” she tells him, her own hand lifting at the same time as his. “A little bit more. Oh, this is so nice!”

A few minutes later, she stands up and suggests that we all take a look at the images. We head downstairs to her computer (which, ironically, sits by a sculpture that closely resembles a marionette). In some of the photos, Stevens’ head and torso are spliced on top of the mannequin and a soft glow around his shoulders gives him the slightest appearance of an archangel. One particular photograph has such a luminous, otherworldly quality that everyone in the room murmurs in delight.

I look at Imboden, and her face has a look of surprise and satisfaction, as if she realizes what she is seeing for the first time. She exclaims, “Isn’t it beautiful?”